Nicaragua: U.S. sanctions will disrupt sustainable beef production and reforestation

By Richard Kohn, Ph.D.

From Columbia, MD

Recently, there have been reports in the news media that Nicaragua is destroying its rain forests and allowing beef ranchers to convert them to pastures in the country’s vast nature reserves. A network of supposed human rights and environmental groups are calling for an increase in the intensity of sanctions against Nicaragua, ending beef imports from Nicaragua, and ending international carbon trading credits that support reforestation programs there.

Contrary to this misleading narrative, the nature reserves in Nicaragua are not being deforested, and the Nicaraguan government has been promoting more sustainable beef production and reforestation. Economic sanctions could jeopardize these efforts.

My personal experience refutes misleading news

I am a professor of animal science at the University of Maryland specializing in evaluating environmental impacts of animal production systems–especially for beef and dairy. I am very familiar with Nicaragua since I lived there from 1987 to 1988 working with ranchers as an extensionist. I have visited since then, most recently in January of 2020 when I attended a study delegation that examined agroecology as practiced in Nicaragua. On this last trip, I started a dialogue with counterparts in my field through the Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (Rural Workers Association) to lay the groundwork for a University of Maryland study abroad course in Nicaragua in agriculture and environmental studies. After seeing the statements in the U.S. media about Nicaraguan beef production that were inconsistent with my first-hand knowledge of the country, I decided to investigate the issue.

Nicaragua is a member of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), which has enabled it to benefit from higher prices for grass-fed beef. In an apparent violation of the agreement, in 2018 the U.S. applied sanctions on Nicaragua that interrupted free trade. These sanctions prevent Nicaragua from obtaining loans from international lending authorities and freeze the foreign assets of many individual Nicaraguans.[1] Now there is a bill called the RENACER Act in front of both houses of Congress[2] which would impose harsh economic sanctions on the country aimed at returning it to extreme poverty in order to help an opposition candidate win this year’s election in Nicaragua. And if that fails, win support for the possibility of a planned coup attempt thereafter.[3]

Support this progressive voice and be a part of it. Donate to COHA today. Click here

Beef production and the environment

The U.S. news media often exaggerate the environmental impact of beef production. For example, articles online and in the popular press attribute as much as 60% of greenhouse gas emissions to consumption of meat. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the actual contribution is estimated to be about 2% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.[4] Fossil fuel production and use is responsible for 90%. A little more greenhouse gas is emitted from production of imported beef, but it doesn’t appreciably affect the total.

The mainstream news media often misinform about beef production to an even greater extent when that beef production occurs in a country the U.S. government has selected for regime change. The percentage of domestic greenhouse gas emissions coming from beef production is higher for Nicaragua than that for the U.S. because Nicaragua has much lower total greenhouse gas emissions from other sources, including fossil fuels. The total greenhouse gas production per capita in the U.S. excluding land use change (mostly from fossil fuels) is eight times higher than for Nicaragua.[5]

Often, reported greenhouse gas emissions from beef production include land-use changes for expanded beef production. Although the estimates published in the mainstream media are often too high, there can be some increase in greenhouse gas emissions from land use change. When land is converted from forest to pasture, less carbon is stored in the forest canopy, and therefore the carbon is presumed to be added to the atmosphere. The deforestation that occurs in developing countries occurs for many reasons besides the need for cattle grazing. Furthermore, when forests are converted to row crops for food production, even less carbon is stored in crop cover and soil compared with either cattle grazing or forestry. The U.S. converted much of its forest to agricultural land decades ago, so currently there isn’t much land use change associated with conversion of forests to agriculture in this country. In developing countries however, ongoing land use change accounts for a significant percentage of estimated greenhouse gas emissions.

International climate agreements such as the Paris Accords charge each country with decreasing greenhouse gas emissions by a similar percentage irrespective of what industries they have, what products they import or export, or whether they already have low greenhouse gas emissions. Countries that already have low greenhouse gas emissions could have a more difficult time cutting the few emissions they have; reforestation is one option. Reforestation decreases estimates of global greenhouse gas emissions no matter where the reforestation occurs, but developing countries face greater pressure to protect and replant their forests since they can’t decrease greenhouse gas emissions as easily as wealthy countries by using less fossil fuel because they already use very little.

A little summary on U.S. intervention in Nicaragua

For many years, Nicaragua exported beef as well as coffee and bananas, and the U.S. government supported international agribusinesses and the wealthy landowners in that country. The U.S. Marines invaded Nicaragua in 1909 to protect U.S. investments. A Nicaraguan revolutionary, Augusto Sandino, fought a guerilla campaign that ousted the U.S. Marines in 1933. The U.S. then negotiated the installation of one of the world’s most notorious dictators, Anastasio Somoza, whose family ruled Nicaragua until 1979. A guerrilla army calling itself the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front, or FSLN), or Sandinistas, deposed the Somoza dynasty after 45 years of dictatorship. The Sandinistas established democratic elections and converted themselves from guerrilla army to political party. Many wealthy landowners fled the country and the new government redistributed abandoned properties to peasant farmers.[6]

Then the U.S. organized the so-called Contras–right wing rebel groups, including former Somoza National Guard fighters in Honduras– who crossed over the border at night and attacked the symbols of the Sandinista revolution: healthcare clinics, schools, and of course, small farms. Most of the fighting was in rural areas. This, together with a harsh economic embargo and the mining of Nicaragua’s harbors by the CIA, soon had the country mired in more poverty and hardship. A U.S.-backed Presidential candidate won elections in 1990 even though most people polled supported the Sandinistas but were tired of war. Three successive neo-liberal governments ruled Nicaragua over the next 16 years. Facing continued poverty, the population re-elected Daniel Ortega from the FSLN Party as President in 2006, and he has repeatedly won re-election thereafter. Since the Sandinistas returned to office, poverty and extreme poverty decreased to half of previous levels; literacy and healthcare have improved; and many indigenous people have been given title to collectively own land in eastern Nicaragua.[7]

The previous U.S.-backed governments in Nicaragua re-directed the economy toward servicing the interests of the United States: large private farms were engaged exclusively in export agriculture while most landless peasants went hungry. Since 2007 the Sandinistas have diversified agriculture to meet the needs of their own population. Although the Sandinistas support a variety of food production practices, and the country has become more than 90% food self-sufficient,[8] the export of crops like beef and coffee is still important to Nicaragua’s economy. Increasing sanctions by stopping export of beef to the US would be yet another blow to the country’s efforts to improve the standard of living of its people.

Improved cattle management in Nicaragua

Cattle do contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, but proper management can mitigate this. Good cattle feeding and waste management practices can decrease methane and nitrous oxide emissions, and cropping and grazing practices can either deplete or accumulate carbon stores in soils and crops. In many parts of Nicaragua, grass-fed beef ranching and milk production are practiced sustainably, and several beef and dairy producers’ organizations have recently signed an agreement to promote more sustainable practices.[9] Managing cattle for faster rates of growth is one way to decrease emissions of the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide. U.S. beef production is highly efficient in this regard, but there is a lot of opportunity in Nicaragua to improve pastures’ ability to support faster growth by using more digestible plants.

Another sustainable practice is to have continuous pastures with trees that constantly build and trap organic matter in soils. This is particularly helpful since much of Nicaraguan land is too hilly or receives too little rainfall to be suitable for annual row crops; torrential rains routinely come at the end of the dry season, washing away soils on any hilly fields that lack groundcover. When forests on steep slopes are destroyed and carelessly converted to agriculture without consideration of the long-term potential for erosion, soil carbon can be depleted and soon the tired soils also produce less vegetation. The carbon lost is added to the air. Here, mitigation by including trees in pastures is important. Although forests capture more carbon than pastures, trees in pastures grow faster and trap more carbon per tree. In 2020, I showed a picture to a Nicaraguan farmer of a beautiful pasture with trees interspersed within it and framed by rustic fence posts. He said it was nice, but they should have used trees in place of the fence posts, as is now the norm. He was right and there definitely have been campaigns to improve grazing practices and plant more trees.

A final point to bear in mind is that the beef industry brings significant revenue to the country—money that is currently used for poverty alleviation programs and reforestation—but has a small impact on U.S. industry. The 700 million U.S. dollars Nicaragua exports annually in beef and dairy accounts for 25% of the nation’s foreign exchange, but only 5% of the U.S.’ imports (after Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Mexico.)[10]

Nicaragua and its programs to replant trees

The Nicaraguan government has been using carbon trading programs to incentivize tree planting and improve pastures with more nutritious plants. These practices decrease the greenhouse gas impact of beef ranching in Nicaragua.

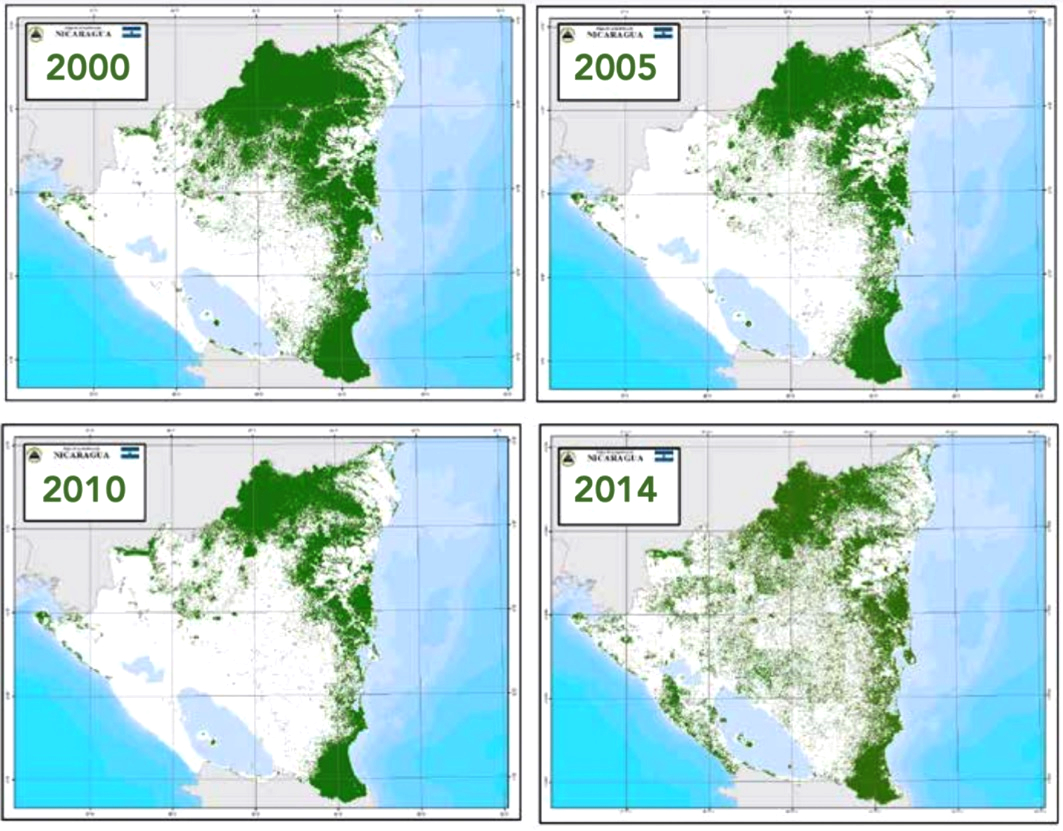

The World Bank published the tree coverage maps in Figure 1.7 Much of the deforestation had already occurred before the Sandinistas returned to power, as one can see from thinning of the forests in the northeast between 2000 and 2005 during the end of the neoliberal governments, and further thinning in the region between 2010 and 2014. This territory is controlled by indigenous communities and they have developed some of it for domestic use in crops and livestock, but the large natural reserves remain. The 2014 map shows recovering tree coverage once trees were planted throughout the country since the Sandinistas returned to power in 2007.

False news that doesn’t recognize Nicaragua’s success

The mainstream news media and websites claiming to represent environmental organizations have been calling to defund Nicaragua. They accuse the Sandinistas of contributing to climate change by destroying forests to convert land to pastures to export beef. For example, last October, PBS Newshour ran a story called “Conflict Beef”, claiming that indigenous people were being run off their land and killed to make room for more cattle ranching.[11] They claimed the disputes were driven by the sudden increase in demand for beef in the U.S. because of lower domestic beef production due to the pandemic. The implication was that the U.S. should stop importing beef from Nicaragua for humanitarian reasons. It should be noted that according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there were no increases in beef imports to the U.S. from Nicaragua during the pandemic.[12] Furthermore, the large nature reserves in Nicaragua have not been deforested, and although there have been illegal land grabs in some remote areas, the government has been attempting to prevent them.

Some groups have called for the World Bank to stop funding Nicaragua’s reforestation programs. For example, the anti-Sandinista environmental organization COCIBOLCA, which is led by the celebrity Bianca Jagger, opposes World Bank funding of reforestation programs in Nicaragua.[13] The Nicaraguan anti-Sandinista newspaper La Prensa reported[14] that funding for the program to continue reforestation in Nicaragua has already been canceled according to sources from the World Bank. However, reports in La Prensa are often inaccurate, and information directly from the World Bank has indicated a high level of satisfaction with the Nicaraguan government’s administration of its programs. [15]

Whether or not international funding for reforestation has already been cut, pressure from the vast media network against Nicaragua will be used to continue pushing for more sanctions and more interference with its economy.

U.S. sanctions have the potential to create a large impact on Nicaragua’s forests. It is the small military and police force that are charged with protecting land resources and indigenous people who live in remote forested areas, and US sanctions directly target those entities. The latest round of sanctions before the U.S. Congress will completely embargo supplies to the military and police from imported goods from the U.S., for example. Other U.S. sanctions block international funding for programs in Nicaragua which may include reforestation programs. Because the U.S. sanctions are broad and vague and the enforcement is arbitrary and severe, there is a real risk of over-enforcement in which investors avoid Nicaragua all together. The economic damage done by the sanctions will force the Nicaraguan government to choose between feeding the population and preserving the forests, as it will likely no longer be able to do both.

Campaign to benefit U.S. political allies in Nicaragua

The carbon footprint of the average Nicaraguan is miniscule compared to that of the average U.S. citizen. The Sandinista-led government has been planting trees and improving environmental efficiency of beef production while the previous U.S.-backed administrations saw the overharvesting of forests to increase beef exports.

The result of current and proposed U.S. sanctions on Nicaragua will be to plunge the country back into poverty, increase hunger, and prevent Nicaragua from decreasing its greenhouse gas emissions. The objective is to blame all of these problems on the Sandinistas in order to favor candidates that will better serve the interests of U.S. corporations. Those interests include the deregulated cheap exploitation of Nicaragua’s labor, land, and other natural resources.

Therefore, sanctions on Nicaragua are likely to increase greenhouse gas emissions whether or not they cause the replacement of the Nicaraguan government.

Richard Kohn is a professor of Animal Science at the University of Maryland. His research interests include evaluating the environmental impacts of animal production systems.

[Main photo: Pasture in Estelí Department, Nicaragua. The long dry season and low water table limit the amount of row crops that can be grown. Stockpiled pastures like this keep the ground covered to prevent erosion. Photo credit: R. Kohn, 2020]

Sources

[1] Nicaragua Human Rights and Anticorruption Act, 2018. House Resolution 1918. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1918

[2] RENACER Act, 2021. Senate Bill 1041 and 1064. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1041

[3] Perry, J. The US contracts out its regime change operation in Nicaragua. Council on Hemispheric Affairs. August 4, 2020. https://coha.org/the-us-contracts-out-its-regime-change-operation-in-nicaragua/

[4] US Environmental Protection Agency, 2021. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Agricultural Sector Emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[5] https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?breakBy=countries&calculation=PER_CAPITA&end_year=2018®ions=NIC%2CUSA§ors=total-excluding-lucf&source=CAIT&start_year=1990

[6] Collins, J. 1982. What Difference Could a Revolution Make? Food and Farming in the New Nicaragua. Institute of Food and Development Policy.

[7] World Bank 2021. World Bank Data: Country Specific, Nicaragua. Accessed May, 29, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/country/NI

[8] World Bank 2015. Agriculture in Nicaragua: Performance, Challenges, and Options.

[9] Cattle and Dairy Sector Signs Environmental Sustainability Agenda. Yahoo Finance (online) https://finance.yahoo.com/news/cattle-dairy-sector-signs-environmental-110000324.html

[10] United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Data downloaded July 6, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data/

[11] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ULooc8pdJ4

[12] United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Data downloaded July 6, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-international-trade-data/

[13] López, L. B. 2019. Dictadura de Nicaragua da por hecho que echó mano a los 55 millones de dólares de los fondos verdes del Banco Mundial. La Prensa, Nov. 14, 2019. https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2019/11/14/nacionales/2610668-dictadura-de-nicaragua-fondos-verdes-del-banco-mundial.

[14] Estrada Galo, J. 2021. Banco Mundial niega al régimen fondos por US$55 millones para la reducción de emisión de carbono. La Prensa, Feb. 24, 2021. https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2021/02/24/nacionales/2788559-banco-mundial-niega-al-regimen-fondos-por-55-millones-para-la-reduccion-de-carbono

[15] Scott Kinnon. 2020. Letter to COCIBOLCA from World Bank on the effectiveness of Nicaragua’s reforestation programs. Sep. 23, 2020. https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/system/files/documents/Bank%20response%20to%20Letter%20from%20environmental%20organizations%20in%20Nicaragua.pdf