Bolivia’s Struggle to Restore Democracy after OAS Instigated Coup

Support this progressive voice and be a part of it. Donate to COHA today. Click here

Frederick B. Mills, Rita Jill Clark-Gollub, Alina Duarte

From Washington DC

On October 21, 2019, the Organization of American States (OAS) issued a fateful communique on the presidential elections in Bolivia: “The OAS Mission expresses its deep concern and surprise at the drastic and hard-to-explain change in the trend of the preliminary results revealed after the closing of the polls.”[1] The mission’s report came in a highly polarized political context. Rather than wait for a careful and fair-minded analysis of the election results, it raised unsubstantiated doubts about the legitimacy of President Evo Morales’ lead as some of the later vote tallies were being reported. This was a bombshell report at a time when it appeared that Morales had garnered a sufficient margin of victory over his right wing opponent, Carlos Mesa, to avoid a runoff election.

The manufactured electoral fraud was quickly debunked by experts in the field. Detailed analyses of the election results were conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR)[2] and Walter R. Mebane, Jr., professor of Political Science and Statistics at the University of Michigan in early November 2019.[3] These were later corroborated by researchers at MIT’s Election Data and Science Lab[4] and more recently by an article published by the New York Times[5] featuring the study of three academics: Nicolás Idrobo (University of Pennsylvania), Dorothy Kronick (University of Pennsylvania), and Francisco Rodríguez (Tulane University)[6].

All of these professional and academic analyses found the charges of fraud by the OAS to have been unfounded.

The OAS electoral mission, however, had already poisoned the well. The false narrative of electoral fraud gave ammunition to anti-Bolivarian forces in the OAS and the right wing opposition inside Bolivia to contest the outcome of the election and go on the offensive against Morales and his party, the Movement Towards Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo, MAS). During a three-week period, a right wing coalition led protests over the alleged electoral fraud, while pro-government counter protesters defended the constitutional government. The military and police cracked down on the pro-Morales protesters, while showing sympathy for right wing demonstrators. Then, on November 10, 2019, in its “Electoral integrity analysis,” the OAS doubled down on its dubious claims, impugning “the integrity of the results of the election on October 20, 2019.”[7]

The track record of the OAS electoral mission, which was invited to observe and assess the election by the Bolivian government of Evo Morales, had already been stained by its 2015 debacle in Haiti.[8] In the case of Bolivia, the mission politicized election results and set the stage for murder by a coup regime. It appears that there is not much political daylight between the judgment of the OAS electoral commission and the rabidly anti-Bolivarian OAS Secretary, Luis Almagro. Far from finding that the coup against Morales constituted a breach in the democratic order of Bolivia, the OAS simply exploited its position as arbiter of the election to rally behind the right wing coup leaders.

Morales resigns and a “de facto” right wing regime unleashes a wave of repression

Despite the relentless drive by Washington against Bolivarian governments in the region, President Morales was apparently unprepared for the disloyalty within his security forces and he was caught off guard by the OAS propensity to serve US interests in the region. MAS activists, legislators, union activists, Indigenous organizations, and social movement activists, however, continued to resist the coup even as they faced arrest and violence from the de facto regime.

The coup forces exercised extreme violence against authorities of the Morales’ administration and MAS legislators (the majority of Congress). Several houses were burned down and some relatives of authorities were kidnapped and injured, all with total impunity and without protection by the security forces.[9]

With the OAS-instigated coup gaining traction within the security forces and police, as well as Morales’ political adversaries, the President chose the path of accommodation. He offered to reconstitute the electoral authority and hold fresh elections. This concession to OAS authority was met by calls from the police and military for his resignation. Rather than launch a campaign of resistance from the MAS stronghold of Chapare, Morales resigned his post, opting for exile in an unsuccessful bid to avoid further bloodshed. Jeanine Áñez, an opposition party senator with Plan Progreso para Bolivia Convergencia Nacional, proclaimed herself President after the resignation of Senate President Adriana Salvatierra, who refused to legitimize the coup with an unjustified “succession.”[10]

The scenes in the streets of Cochabamba turned ugly. It was a field day for racist attacks on the majority Indigenous population. The Indigenous flag–the wiphala–was burned in the streets, and much fanfare was made when Áñez, surrounded by right wing legislators, held up a large leather bible and declared, “The Bible has returned to the palace.” Such attempts to resubordinate Bolivia’s plurinational heritage were met with widespread resistance.

After thirteen years of impressive economic growth, poverty reduction, recovery of the nation’s natural resources, and the inclusion of formerly marginalized sectors in the political life of the country under the leadership of President Evo Morales, Bolivia had now suffered an enormous blow to the liberatory project of the 2009 Constitution. But the coup fit perfectly into the US-OAS drive to recolonize the Americas.

Secretary General Luis Almagro, who would never let an opportunity to attack the Bolivarian cause go to waste, immediately recognized self-proclaimed President, Senator Jeanine Áñez, adding yet one more crime to the long list from his shameful tenure at the OAS.[11] At a special meeting of the OAS on November 12, 2020 Almagro declared, “There was a coup in the State of Bolivia; it happened when an electoral fraud gave the triumph to Evo Morales in the first round.”[12]

During the meeting, 14 member states of the OAS (Argentina, Brasil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, the US, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Peru) and the unelected US-backed shadow government of Venezuela called for new elections in Bolivia “as soon as possible,” while Mexico, Uruguay and Nicaragua warned against the precedent being set by the “coup” against Evo Morales. The ambassador of Mexico to the OAS, Luz Elena Baños, described the coup against Morales as “a serious breach in the constitutional order by means of a coup d’etat,” adding “the painful days when the Armed Forces sustained and deposed governments ought to remain in the past.” [13] The Trump administration echoed Almagro’s declaration and moved quickly to endorse what was now a “de facto” government.[14] The OAS was now at the service of two unelected, US-backed, self-proclaimed presidents (Juan Guaidó for Venezuela and Jeanine Áñez for Bolivia).

What followed was the brutal repression of widespread protests amid grass roots clamor for the return of President Morales,[15] who, from his exile in Mexico and later Argentina, still held great clout among rank and file MAS militants and the popular movements. The horrific massacre in Sacaba, on November 15, followed by a massacre in Senkata, on November 19, carried out by the security forces, exposes the coup regime to future prosecution for crimes against humanity.[16] Rather than pacify the country, the repression only galvanized the MAS, which still held a majority in the legislature, as well as the peasant unions and grassroots organizations in their struggle to restore Bolivian democracy. There was indeed a coup, but it had not and still has not been consolidated.

New elections could be compromised by lawfare

Today, Bolivia stands at a crossroads. In June 2020, popular calls were mounting for new elections and the restoration of democracy, despite the ongoing repression. In response to this pressure, on June 22, Áñez signed off on legislation to hold new elections in September. Former president Carlos Mesa (2003-2005) of the right wing Citizens Community Party would face off against the MAS candidate, former Minister of Finance (2006-2019), Luis Arce. Áñez’s decision drew the ire of Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, who characterizes the most popular political party in the country as narco-terrorist. Murillo even threatened MAS legislators with arrest if they refused to approve promotions for the very military officials responsible for the repression.[17]

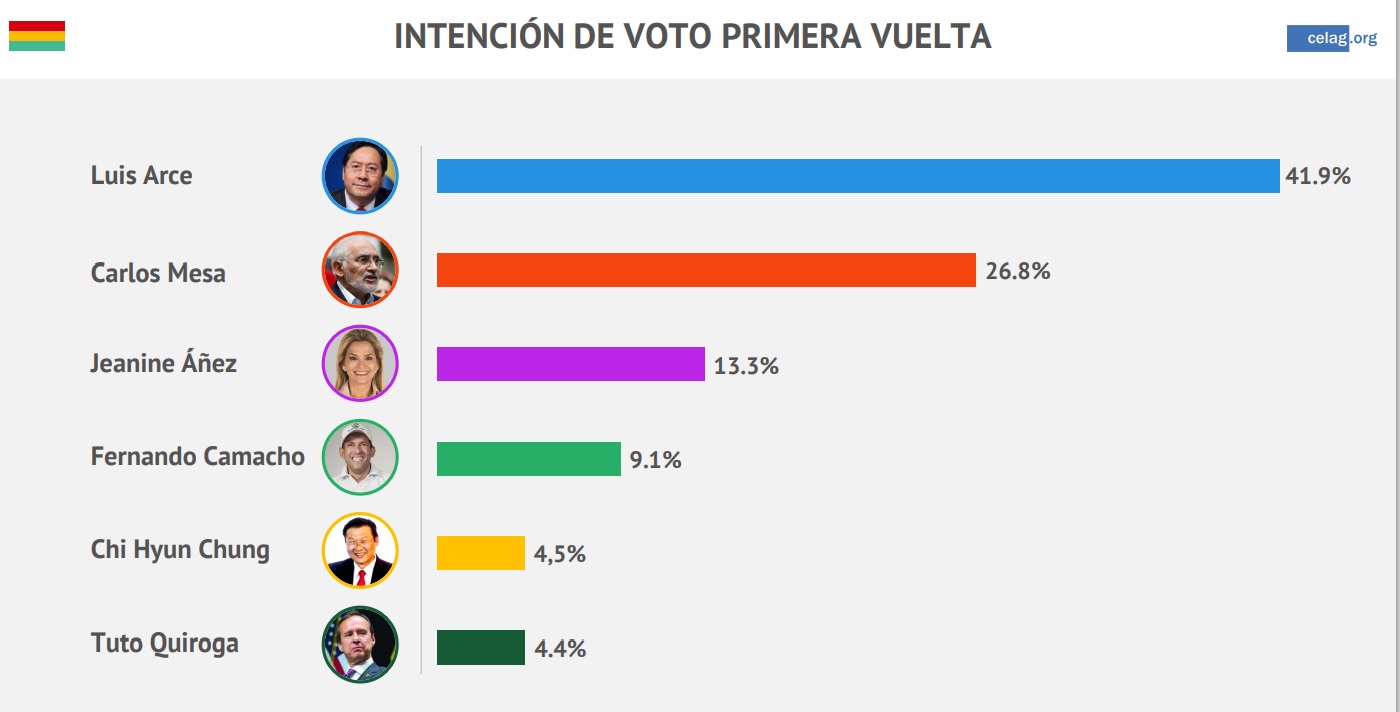

Should democratic elections prevail, recent polls do not look good for the “de facto” regime. In a poll taken by CELAG between June 13 and July 3, the MAS candidate, Luis Arce, leads with 41.9% support, followed by Carlos Mesa, with 26.8%, and Áñez, with 13.3%.[18]

Although Áñez initially said she would not run for president,[19] she later decided to do so even over the objections of her fellow opposition members.[20] The latter said that this went against her purported objective of only serving as a transition government until new elections could be held—initially on May 3, but later canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only was Áñez never a favorite in the polls, her de facto government has been unrelenting in its attempts to persecute the MAS and kick it out of the race.

On March 30 a government oversight agency (Gestora Pública de Seguridad Social de Largo Plazo) filed formal charges against MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce for “economic damages to the State” while he was Minister of Finance. According to the Bolivian Information Agency, his alleged crimes are linked to the contracting of two foreign companies to provide software for the administration of the national pension system.[21]

The charges state that the previous administration paid US$3 million as an advance for a contract valued at US$5.1 million to the Panamanian company Sysde International Inc. However, said company never delivered the software. Consequently, the MAS administration contracted the Colombian company Heinsohn Business Technology for US$10.4 million, on top of which payments were to be made of US$1.6 million annually for the license and source code.

Luis Arce responded to the charges during a press conference,[22] stating that during his tenure, “We entered into a contract for a system and the company failed us, so we filed suit against the company.” But he stressed that the charges simply seek to disqualify the MAS to prevent the party from participating in the presidential election.

Evo Morales took to Twitter to say, “The imminent electoral defeat of the de facto government is leading it to trump up new charges against the MAS-IPSP every day. Now, as we have denounced, they have filed charges based on false conjecture against our candidate to ban him from running for office because he is leading in the polls.”[23]

On July 6, the Attorney General of Bolivia charged Evo Morales himself. The charges are terrorism and financing of terrorism coordinated from exile, and preventive detention has been requested. This is a rehashing of similar charges brought last November, charges denied by Morales.[24]

The persecution against the overthrown government has not stopped. Seven former officials remain asylees at the Mexican Embassy in La Paz: the former Minister of the Presidency, Juan Ramón Quintana Taborga; the former Minister of Defense, Javier Zavaleta; the former government minister, Hugo Moldiz Mercado; the former Minister of Justice, Héctor Arce Zaconeta; the former Minister of Cultures, Wilma Alanoca Mamani; the former governor of the Department of Oruro, Víctor Hugo Vásquez; and the former director of the Information Technology Agency, Nicolás Laguna.

The current Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, affirmed upon assuming power that the authorities of the constitutional government of Evo Morales would be “hunted” and imprisoned before any arrest warrant was issued.[25] And now, eight months after the coup d’etat, the de facto government has refused to deliver safeguards to the asylum seekers at the embassy even though Bolivia and Mexico are parties to the American Convention on Human Rights, which in its article 22 establishes the right to seek and receive asylum[26].

Calls for free and fair elections without subversion by the OAS

The consequences of the OAS’ bad faith monitoring of the 2019 Bolivian election cannot be overstated. Not only were lives lost in the chaos and violence spurred by the statements of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission, which also resulted in scores of injuries and detentions. But the de facto regime continues its reign of terror, even repressing people protesting hunger during the pandemic lockdown,[27] while it dismantles the extensive social programs put into place during the years of MAS government.[28] Despite the repression, grassroots social movements in Bolivia, most notably peasant and Indigenous women who have bravely withstood attacks by the de facto regime, continue to insist on true democracy. They are inspired by the 2009 Constitution creating the Plurinational State, with its promise of a “democratic, productive, peace-loving and peaceful Bolivia, committed to the full development and free determination of the peoples.”[29]

On July 8, the MAS-IPSP “categorically” rejected the participation of an OAS electoral mission for the September presidential election, on account of their responsibility for the coup against the constitutional government.[30] The communique declared that “it is not ethical for [the OAS electoral mission] to participate again for having been part of and complicit with a coup against the democracy and Social State of Constitutional Law of Bolivia”, and “that [the OAS] is not an impartial organization to defend and guarantee peace, democracy and transparency, but rather a sponsor of petty interests that are foreign to the democratic will of the Bolivian people.” [31]

Bolivia is at a crossroads. Will the de facto regime of Jeanine Áñez, having completed a coup and in command of the security forces, allow a return to democratic procedures to resolve political differences? Or will she join her Minister of Government, Arturo Murillo, in seeking to undermine, through political persecution and lawfare, any chance that the MAS ticket will be on the ballot, let alone allow free elections to take place?

The condemnation of the coup by Mexico, Nicaragua and Uruguay on November 12 was just the start of international solidarity with the call for a return to democracy in Bolivia. On November 21, 31 US organizations denounced “the civic-military coup in Bolivia.” [32] On June 29, 2020 the Grupo de Puebla, a forum that convenes former presidents, intellectuals, and progressive leaders of the Americas, released a statement condemning the actions of the OAS. “The Puebla Group considers that what happened in Bolivia casts serious doubts on the role of the OAS as an impartial electoral observer in the future.”[33] The international community can honor the clamour for free and fair elections in Bolivia by condemning the de facto regime’s use of political persecution and lawfare, supporting democratic elections in September, and rejecting any further role of the OAS in monitoring elections in the Americas.

Patricio Zamorano provided editorial support and research for this article.

Translations from Spanish to English are by the authors.

Main photo: Protest in front of the OAS building to oppose the coup, November 2019. Credit: Cele León)

End notes

[1] “Statement of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Bolivia,” https://www.oas.org/en/media_center/press_release.asp?sCodigo=E-085/19

[2] “What Happened in Bolivia’s 2019 Vote Count?” https://cepr.net/report/bolivia-elections-2019-11/

[3] “Evidence Against Fraudulent Votes Being Decisive in the Bolivia Election,” http://www-personal.umich.edu/~wmebane/Bolivia2019.pdf

[4] “Bolivia dismissed its October elections as fraudulent. Our research found no reason to suspect fraud,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/26/bolivia-dismissed-its-october-elections-fraudulent-our-research-found-no-reason-suspect-fraud/

[5] “New York Times Admits Key Falsehoods that Drove Last Year’s Coup in Bolivia: Falsehoods Peddled by the US, its Media, and the Times,” https://theintercept.com/2020/06/08/the-nyt-admits-key-falsehoods-that-drove-last-years-coup-in-bolivia-falsehoods-peddled-by-the-u-s-its-media-and-the-nyt/. See also the study by CELAG, “Sobre la OEA y las elecciones en Bolivia”, (Nov. 19, 2019). CELAG conducted a study of both the OAS report and CEPR’s analysis and concluded: “The findings of the analysis allow us to affirm that the preliminary report of the OAS does not provide any evidence that could be definitive to demonstrate the alleged “fraud” alluded to by Secretary General, Luis Almagro, at the Permanent Council meeting held on November 12 . On the contrary, instead of sticking to a technically grounded electoral audit, the OAS produced a questionable report to induce a false deduction in public opinion: that the increase in the gap in favor of Evo Morales in the final section of the count was expanding by fraudulent causes and not by the sociopolitical characteristics and the dynamics of electoral behavior that occur between the rural and urban world in Bolivia.” https://www.celag.org/sobre-la-oea-y-las-elecciones-en-bolivia/

[6] “Do Shifts in Late-Counted Votes Signal Fraud? Evidence From Bolivia,” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3621475

[7] “Preliminary Findings Report to the General Secretariat,” http://www.oas.org/documents/eng/press/Electoral-Integrity-Analysis-Bolivia2019.pdf

[8] “Elections in Haiti pose post-electoral crisis, by Clément Doleac and Sabrina Hervé, Dec. 10, 2015. COHA. https://coha.org/elections-in-haiti-pose-post-electoral-crisis/

[9] “El Grupo de Puebla rechazó el golpe contra Evo Morales y se solidarizó con el pueblo boliviano,” https://www.infonews.com/el-grupo-puebla-rechazo-el-golpe-contra-evo-morales-y-se-solidarizo-el-pueblo-boliviano-n281357

[10] “Salvatierra: Mi renuncia fue coordinada con Evo y Alvaro,” https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2020/1/24/salvatierra-mi-renuncia-fue-coordinada-con-evo-alvaro-244454.html&sa=D&ust=1593696030403000&usg=AFQjCNE_kAMqtAOBGCXdjJV5nkBsfQEWPQ

[11] “Almagro: Evo Morales fue quien cometió un “golpe de Estado,” DW. https://www.dw.com/es/almagro-evo-morales-fue-quien-cometi%C3%B3-un-golpe-de-estado/a-51218739

[12] https://twitter.com/oas_official/status/1194389549037830145?lang=en

[13] “La OEA y la crisis en Bolivia: un choque de relatos irreconciliables”, EFE, Nov. 12, 2019. https://www.efe.com/efe/usa/politica/la-oea-y-crisis-en-bolivia-un-choque-de-relatos-irreconciliables/50000105-4109588

[14] “Statement from President Donald J. Trump Regarding the Resignation of Bolivian President Evo Morales,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-donald-j-trump-regarding-resignation-bolivian-president-evo-morales/

[15] “With the Right-wing coup in Bolivia nearly complete, the junta is hunting down the last remaining dissidents,” https://thegrayzone.com/2019/11/27/right-wing-coup-bolivia-complete-junta-hunting-dissidents/

[16] “Brutal Repression in Cochabamba, Bolivia: So far nine killed, scores wounded,” COHA. https://coha.org/brutal-repression-in-cochabamba-bolivia-november-15-2019/

[17] “Bolivian regime threatens to imprison lawmakers, officials,” https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Bolivian-Regime-Threatens-to-Imprison-Lawmakers-Officials-20200524-0004.html

[18] “Encuesta Bolivia, July 2020”, CELAG, https://www.celag.org/encuesta-bolivia-julio-2020/

[19] “Evo Morales busca un candidato y Añez dice que no participará en elecciones”, https://www.lavoz.com.ar/mundo/evo-morales-busca-un-candidato-y-anez-dice-que-no-participara-en-elecciones

[20] “A Jeanine Añez hasta los aliados le critican su candidatura”, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/244221-a-jeanine-anez-hasta-los-aliados-le-critican-su-candidatura

[21] Gestora Pública denuncia formalmente al exministro Luis Arce por daño económico al Estado” https://www1.abi.bo/abi_/?i=452014

[22] “Luis Arce asegura que la denuncia en su contra busca inhabilitar su participación en las elecciones”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DYvPUk643w

[23] “Fiscalía boliviana acusa de terrorismo a Evo Morales.” https://www.eltiempo.com/mundo/latinoamerica/fiscalia-boliviana-acusa-de-terrorismo-a-evo-morales-515054

[24] “Fiscalía boliviana acusa a Morales de terrorismo y pide su arresto,” https://www.hispantv.com/noticias/bolivia/470654/anez-morales-terrorismo-detencion

[25] “¿Quién es Arturo Murillo?”, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/239232-quien-es-arturo-murillo

[26] “American Convention on Human Rights,” https://www.cidh.oas.org/basicos/english/basic3.american%20convention.htm

[27] “Valiente resistencia en K’ara K’ara enfrenta represión policial y militar”, https://www.laizquierdadiario.com/Valiente-resistencia-en-K-ara-K-ara-enfrenta-represion-policial-y-militar

[28] “Bolivia’s Coup President has Unleashed a Campaign of Terror,” https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/05/bolivia-coup-jeanine-anez-evo-morales-mas

[29] “Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Constitution of 2009,” https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Bolivia_2009.pdf

[30] MAS-IPSP tweet, July 8, rejecting OAS mission for September elections.

[31] “El MAS rechaza observadores de la OEA en elecciones bolivianas,” July 9, Telesur. https://www.telesurtv.net/news/bolivia-movimiento-socialismo-rechazo-observadores-oea-20200709-0002.html

[32] “31 US organizations denounce the brutal repression in Bolivia,” COHA. https://coha.org/31-us-organizations-denounce-the-brutal-repression-in-bolivia/

[33] ttps://www.telesurtv.net/news/grupo-puebla-rechaza-oea-observador-internacional-20200629-0085.html