Despite US led Dirty Campaign, Nicaraguans Came Out in Force in Support of the FSLN

By Rita Jill Clark-Gollub

Managua, Nicaragua

Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council declared President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) winners in an election that drew 65% of the eligible 4.4 million voters. Although Washington and its allies in the region denounced the election as a fraud preceded by repression of the opposition, there was significant participation of the electorate; moreover, despite claims that Ortega ran virtually unopposed, his ticket was contested by several long-standing opposition parties. Winning 75% of the vote, the FSLN demonstrated solid strength despite the U.S. government and mainstream media campaign to delegitimize this election.

Rita Jill Clark-Gollub shares her report from the ground in Nicaragua:

On Sunday, November 7, 2021, millions of Nicaraguan voters showed up at the polls to cast their votes in an orderly, calm election process. I was one of over 165 international accompaniers and at least 40 independent international journalists who collectively observed the vote at about 60 voting centers in 10 of Nicaragua’s 15 departments as well as its two autonomous regions.

Gender equity

Two pieces of background information provide helpful context. First, the Nicaraguan constitution creates an independent, non-partisan fourth branch of government to run elections, the Supreme Electoral Council (CSE). Second, the electoral law was updated this year to bring computer technology into the system, and to bring gender equity to the staff running the elections, thus completing implementation of the gender parity law passed in 2014. This means that all aspects of the CSE must be staffed with an equal number of men and women, and half of all poll workers, including poll watchers designated by the various political parties, must be women.

My observations were in the country’s second largest city, León. My first stop was a voting center at a school in the indigenous neighborhood of Subtiava, where 5,000 people are registered to vote.

Day of the election

Voters had shown up before the doors opened at 7:00 AM, and by 7:40, 500 people had already voted. A voter’s experience started by checking-in with staff manning four laptops. There had been a massive update and confirmation of the voter rolls earlier this year that informed people of their polling places. Voters were able to verify this information on paper and online, which minimized any issues at check-in. On election day, the entire voter roll for the individual voting centers was posted outside. This not only confirmed to people their voting place, but also allowed neighbors to identify names that should not be on the rolls, such as people who had died or moved away. Because of these updates and use of electronic tools, the check-in process was more efficient than people remembered in the past. Some of my fellow accompaniers even timed voters’ experiences and found the whole process usually took less than nine minutes.

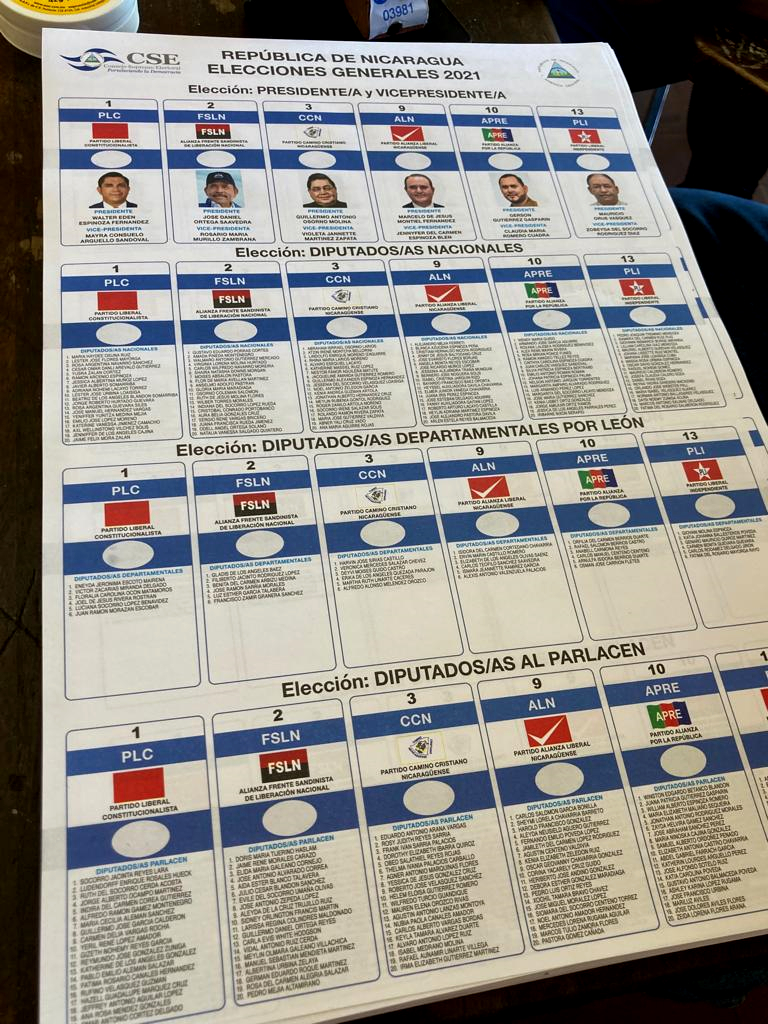

After a voter checked in, he or she went to one of 13 classrooms to cast their vote. These are called Juntas Receptoras de Votos (Vote Intake Boards–JRV). Each one is designated to serve between 380-400 voters. Again, the voter roll for that JRV is posted outside the door. When voters came in, they gave their name to the three CSE workers who then checked them off on a paper printout of the roll. Then the CSE checked to find the voter on the pages with printouts of government-issued photo identification cards, and had the voter sign under their picture. After that they were given a copy of the ballot and directed to the three voting booths to mark the ballot. As you can see from this photo of the ballot, it is rather straightforward in showing the various parties running for President and Vice-President, National Assembly, and Central American Parliament. Voters then placed their folded ballots into the ballot boxes. After that, one of the three CSE members proceeded to mark the voters’ thumbs with indelible ink so that they could not vote twice.

Also present in the room were poll watchers (each party on the ballot is allowed to have a poll watcher present in each JRV for the entire election day) and elections police. The latter primarily provide alcohol to disinfect hands (a common practice in Nicaragua during the pandemic) and assist people with mobility issues to move within the classroom, as well as keeping disorderly people (such as drunks), from disrupting the process. I did not witness any such disruptions, nor did I hear of them (no liquor can be sold on election day). An interesting thing about the Nicaraguan voting process is that the vote tally takes place with paper ballots in the same room in which the votes are cast, and in the presence of the poll watchers. The number of ballots counted, plus the unused ballots, must match the number of ballots given to that room at the beginning of the day. A paper copy of the vote count is submitted to the central CSE, and it is also communicated electronically, but it is the paper trail that prevails in this case. Other international accompaniers who have witnessed elections in several countries said that this provides the most secure elections integrity possible.

“Nicaraguans want peace”

I saw this process repeated numerous times in the four voting centers I visited. I also asked people if they would like to answer a question, and virtually everyone I approached was eager to speak. I asked: What is the significance of what is happening in Nicaragua today? The answer was surprisingly unanimous among the dozens of people I spoke to: They said, “Nicaraguans want peace.” They also overwhelmingly said that they want to determine their future for themselves and want respect for their sovereignty without interference from the outside.

Plenty presence of the opposition

I found it particularly interesting to speak to the poll watchers from opposition parties that were present in the voting rooms. It bears noting that five traditional opposition parties, some of which have held the presidency in the 21st century, ran candidates for president, despite the reports we hear from the U.S. about Daniel Ortega eliminating his opponents. I asked them what they thought about participating in this election as part of the opposition. They generally indicated that it had been a smooth and respectful experience. One gentleman from the Independent Liberal Party (PLI) said, “We want to see what the people think. If a majority of people come out to vote—60 or 70 percent—then the election results will tell us what the people want. But if fewer than half of the electorate turns out to vote, that will mean that people felt they did not have a real choice in this election.”

I imagine the PLI will continue to participate in Nicaragua’s democratic process, despite the fact that the U.S. government is calling for sanctions on participating opposition parties, because of the high turnout. The landslide electoral victory indicates a clear mandate to stay on the path the country has been following since Daniel Ortega came back into office in 2007. If I needed further confirmation that this reflected the will of the people, I got it on the way back to my hotel late Sunday night from seeing people dancing in the streets and setting off fireworks in Managua.

Young voters

Another thing that was very palpable about the Nicaraguan elections experience was the massive involvement of young people. Not only were voters as young as 16 years old (the Nicaraguan voting age) turning out in large numbers, they were also working as poll watchers and accompanying entire families during what they called “a civic festival of democracy.”

As in most countries, the youth are big users of social media. But in Nicaragua about a week before the vote, over a thousand of these young people had their social media accounts shut down, causing them to collectively lose hundreds of thousands of followers. The Silicon Valley platforms said they were stopping a Nicaraguan government troll farm. I spoke with several people who were incensed by this because they personally knew real people who were accused of being bots, or were shut down themselves. A young Sandinista named Xochitl shared with me the screenshots of her FloryCantoX account that had 28,228 followers before Twitter shut it down, telling her that she violated their rules on using spam. This also happened to some of the international visitors to Nicaragua. And I have just heard from Dr. Richard Kohn, who was in Nicaragua observing the elections in the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region, that all of his photos and videos uploaded to Twitter on election day were removed.

The lies about the process

I am astounded at reports in the mainstream media and from the Biden administration declaring the vote a fraud, and that as few as 20% of the electorate turned out to vote. This flies in the face of my own experience. If I keep talking about it, will I, too, be accused of being a bot? And what does this information warfare mean for democracy in the United States and the American people’s right to know what is happening in other countries?

The Nicaraguan people know their lived reality. We need to continue helping to disseminate their truth.

[Credit main photo: Rita Jill Clark-Gollub/COHA]