Chile is Reborn by a (Political) Earthquake that Emerged from the Streets

By Patricio Zamorano

From Washington DC

What happened in Chile this past weekend seems to be one of those historic events that cannot but follow its inexorable course. It is like an enormous, powerful tsunami wave whose size cannot be appreciated on the high seas, until it comes crashing into the coast, stunning everyone with its massive strength. This happens with processes of change from the left and the right, in times of democracy and times of dictatorship.

Could any human force have stopped the inexorable onslaught of that immoral showman Donald Trump on his path to the U.S. presidency? Who would have believed that someone so dysfunctional on so many levels could have governed the most powerful country on the planet for four years? He got more than 70 million U.S. votes, making him the Republican to win the most votes in history, legitimizing his political and pseudo-ideological platform, whether we like it or not. His rise to power was unstoppable.

Fidel had the same telluric force of history behind him when 12 disciples of José Martí, decimated by the disastrous landing of the Granma, carried out an impossible revolution from the Sierra Maestra in just three years. This feat has stirred the passions of revolutionaries and reactionaries alike for some 60 years now.

Some political processes are simply unstoppable.

What just happened on May 15 and 16, 2021 in Chile has the same air of the refounding of an entire nation. It means the end of traditional party politics and the establishment of collectives with diverse origins. These collectives are focused on contemporary issues such as the environment, gender equality, local issues against capital centralism (Santiago), and the demands of other emerging sectors.

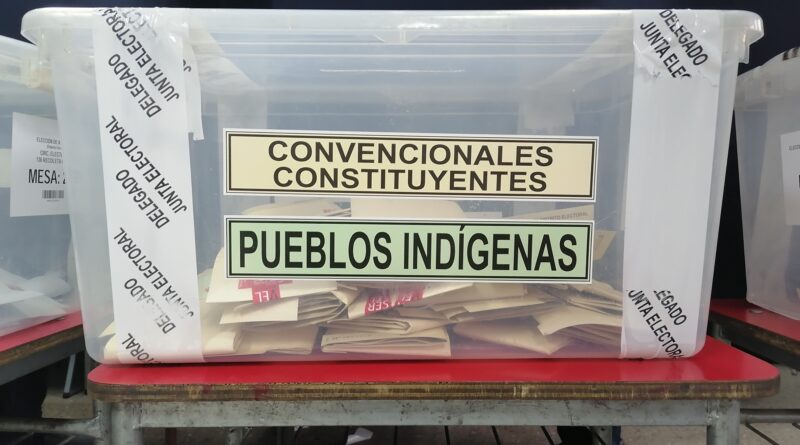

An historic constitutional assembly

First, the numbers. Intense social unrest that raised demands in the streets was met by bloody repression by the security forces which deployed tear gas and rubber bullets, destroying the eyes of dozens of Chileans. The path was opened to something people had thought impossible within formal government institutions: 155 delegates have been elected to draft a new constitution for Chile. These are people from the political class, social movements, grass roots organizations, and many independents. Out of those 155, according to data from the Electoral Service of Chile (SERVEL), 77% identify with left-leaning values, are against Pinochet’s legacy, and reject the neoliberal model founded in the military repression of September 11, 1973.

The right-wing parties banding together in “Vamos Chile” needed 54 delegates to the constituent assembly to break the two-thirds majority and wield veto power. They only obtained 37 seats, which in practice means that they will only have limited power from the political margins.

These results are completely logical. The right-wing parties in Congress, in Sebastián Piñera’s Executive Branch, and in the media have spent all these years systematically blocking all efforts by the country’s majority to reform the healthcare system and make it more just; to reform the education system and make it more accessible to the entire population; and to reform the tax system to make it more equitable. The actual truth is that with an agenda so disconnected from the despair of the overwhelming majority of the Chilean people, the great leaders of the right and of Chilean capital cannot escape their own responsibility for the defeat that befell them last weekend.

The neoliberal ideology pretended to champion markets that would be free from state intervention. Yet as the Chilean experiment demonstrates, it took massive social control by the state with no check and balances (no Congress, no political parties, no social movements), and a harsh reign of terror, to enforce the structural adjustment packages that imposed austerity to facilitate the economic exploitation of human and natural resources. In fact, corporate interests have politically captured the state, putting its institutions at the service of capital, for all governments after Pinochet, both center-left and center-right ones. Furthermore, the promises of “accumulation of capital” for all Chileans that would be created by “trickle-down economics” was a complete failure, except for a minority of those with the highest incomes.

Today’s Chile is advocating with the language of “sexual diversity,” “gender parity,” “equal rights and opportunities,” “inclusion,” “tolerance,” and “social dignity.” Some of the most conservative right-wing Chileans appear disconnected, reactive, and very uncomfortable with this new reality that they have yet to comprehend.

Mayor of Santiago from the Communist Party

The historic gestures are impressive for a conservative country such as Chile. Along with representatives to the constituent assembly, mayors and city council members were also elected.

Santiago, the capital, will now be led by Iraci Hassler as mayor. She is an economist from the University of Chile and notably a member of the Communist Party (CP). Fifty years after the policy of extermination and torture imposed by the Pinochet dictatorship on the Communist Party of Chile (the party of Pablo Neruda, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the great singer-songwriter Víctor Jara), there is no doubt that this electoral victory is a hard symbolic blow to the most conservative, militaristic, and anti-communist sectors of the country. Social media has revealed their ideological anxiety: dozens of memes painting the electoral districts with the symbol of the CP (the hammer and sickle) and words in Russian. This is a reminder of the irrational politics that still run strong among this radical minority in a country undergoing a profound transformation.

There was also an explicit effort to inject gender and cultural parity into the election for the Constitutional Convention, ensuring that at least 45% of the seats went to women and reserving 17 seats for indigenous communities. This is vital to reflect the wishes of the Chilean people when 80% of them voted for a new constitution in the plebiscite of October 2020. The objective of this popular outpouring is to eliminate all anti-democratic provisions inherited from the 1980 militaristic constitution inspired by the Chicago Boys.

Delegates have an opportunity to remove capitalist equations from areas such as health, education, and pensions, returning those key aspects of Chilean life to the category of fundamental social rights. Broadly speaking, delegates can now establish a more just constitutional framework in order to better distribute wealth and income among the whole population and neutralize the country’s tremendous inequality—one of the worst on the planet.

The numbers reflect a seismic shift

In electoral terms, it is a scenario of major change. Valparaíso, the second largest city in the country, was kept by independent leftist Mayor Jorge Sharpo. Viña del Mar, another major urban center near Valparaíso, was carried by Macarena Ripamonti, a member of the new leftist collective Frente Amplio. Frente Amplio is not one of the traditional parties, and has wrested from the right wing a city that normally votes conservative. And in Concepción, independent leftist Camilo Rifo came in second place, leaving the right wing in third.

In Santiago, the right lost large municipalities, including Maipú, Ñuñoa, Estación Central, and San Bernardo, to name a few.

In sum, the entire region around greater Santiago, home to one third of the population (about 6 out of 19 million people), according to SERVEL reports as of today, gave the center-left 27 mayoral offices, while the right only won 14 (of course, including many of the wealthy neighborhoods of eastern Santiago). Add to that total 11 independents.

What’s next

The next steps include the launching of the new Constitutional Convention between June and July of this year. It will have nine to 12 months to draft the new Charter. Approximately 60 days after this task is completed, a new and final plebiscite will be held to approve or reject the new constitution. That is, 2022 should usher in a new constitution for Chile.

Beyond the numbers and electoral engineering, what happened last weekend lends immense legitimacy to what the people have been demanding in the streets, from the grass roots of society. It has left no doubt of the need for the country’s business and financial sectors to take a hard look at the imperious need to support a process of reconstruction, which at the end of the day, their own representative at La Moneda, Sebastián Piñera, was unable to do. Six points of negative growth in 2020, amplified by the pandemic, the social explosion, and chronic inequality in the country have left no room for ideological protectionism among Conservatives.

Either they join the process of change, trying to influence it as much as they can with the seats they have won at the polls, or they remain alienated from millions of families’ longing for recovery—expectations that cannot be held back. The other path is the strategy of failure that they have been implementing throughout Chile’s history: launch a plan to boycott the country’s political and social development, using their de facto power to keep hindering the reforms the country needs. The obstructionist path would hurt their own pocket books, keep the streets in flames, and betray the essential value of “homeland” that supposedly is their most cherished value.

For Chile’s right wing, the popular vote has made it brutally clear: it is time to get on the right side of history.

Patricio Zamorano is a political science academic, journalist and Director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, COHA

Translation by Jill Clark-Gollub, Assistant Editor/Translator at COHA

[Credit photo: Pressenza Agency]