Colombia’s “Invisible Crisis”: Internally Displaced Persons

By: Louise Højen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

Colombia has experienced a number of positive developments in recent years, including a growing and diversified economy, improved relations with neighboring countries such as Ecuador and Venezuela, as well as a the substantial progress of peace talks between the government and internal guerrilla movements promoting a potential end to Colombia’s 50-year long civil war. However, Colombia still faces grave difficulties within the country. As of December 2014, a shocking 5,840,590 people were registered as being internally displaced in Colombia according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), who calls it “Colombia’s Invisible Crisis.”[1] For many years, Bogotá has made insufficient attempts to address and curb this massive crisis, but more challenges lie ahead as this “invisible crisis” continues to grow beyond control.

Armed Conflict and Colombia’s Humanitarian Crisis

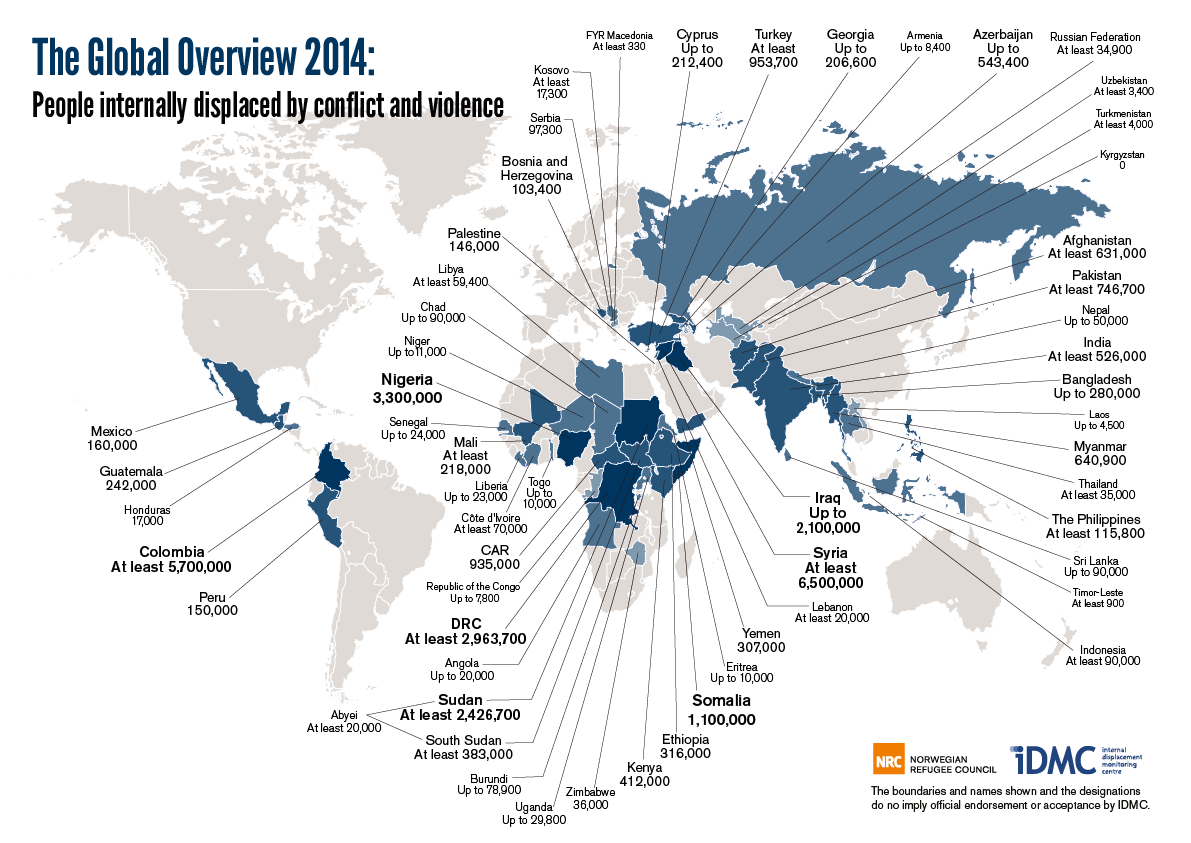

Countries with high rates of internally displaced persons (IDPs) are often plagued by civil war and armed conflict. This correlation is found in Syria, among other fractured societies, which has an astounding 6.5 million IDP’s, the most of any country in the world, according to current data from the UNHCR.[2] Of the 33.3 million IDPs recorded worldwide in 2013, 63 percent come from just five conflict and violence-ridden countries: Syria, Colombia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan.[3] Colombia has been locked in civil war for more than half a century, with government security forces and paramilitary units combating insurgent forces within the country, particularly the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) and the National Liberation Army (ELN, Ejército de Liberación Nacional).[4] However, the real victims of the civil war have been the population who still suffers from the violent encounters between the armed forces and insurgent leftist groups, but also encounters with right-wing paramilitary groups, including U.S.-funded death squads, and the powerful Colombian drug industry.[5]

The internal conflict is widely recognized as the principal reason behind Colombia’s large population of IDPs, though the drug industry also has displaced thousands of people in an effort to expand coca cultivation in areas formerly inhabited by local farmers.[6] According to a report by the Congressional Research Service, most displacements take place in remote rural areas of Colombia where armed conflicts are common, and the majority of IDPs are composed of Indigenous people and Afro-Colombians.[7] This has resulted in increased economic and social inequality as the poor become poorer, and specific ethnic groups suffer more than others do. The Pacific coast departments, such as Chocó, are the most affected areas, accounting for about one third of all Colombian IDPs. Still, almost all regions have experienced displacement caused by violence and conflict.[8] Intra-urban displacement is also increasing due to violent gang conflicts, for example in Medellin, Colombia’s second largest city, notorious for its drug cartels until the 1990s. Nonetheless, the prevailing pattern is displacement flowing from rural to urban settings.[9]

In the 1980s, then President Ronald Reagan officially instigated the war on drugs in Colombia. The United States also backed the counter-insurgency campaign against Colombian guerilla movements, such as the FARC and ELN, but both have proven to be indisputable failures, while at the same time making the United States culpable in aggravating Colombia’s IDPs situation.[10] For example, Washington pledged to financially support the ill-conceived Plan Colombia, signed in 2000, with $4 billion USD to fight drug trafficking and insurgents. A vast majority went to the military especially funding weaponry, while only $30 million USD was allocated to humanitarian aid.[11] Furthermore, Plan Colombia did not deliver the promised results of eradicating either the drug industry or guerrilla movements. Instead, it intensified military deployments, armed violence, human rights abuses by state actors, and internal displacement within Colombia.[12]

Today, the drug industry has not only survived, but remains an important factor in Colombia’s economy by generating an annual profit of almost $9 billion USD.[13] Though both FARC and ELN were profoundly affected under Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2002-2010), they too have resiliently held on and are such influential players within Colombia today that peace talks became the preferred solution to end the long civil war, at least when it comes to President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-present).[14] Despite the haphazard progress of the peace talks, initiated in 2012, FARC recently introduced a unilateral ceasefire, which raises hopes for a de-escalation of the armed conflict; any reduction in the violence would likely mitigate the conditions that cause internal displacement. Additionally, President Santos stated on January 15, 2015, that the Colombian government currently is exploring the possibilities of negotiating a bilateral ceasefire, which could also slow, if not entirely halt, the future number of IDPs.[15]

A Growing Economy Does Not Necessarily Help Colombia’s IDPs

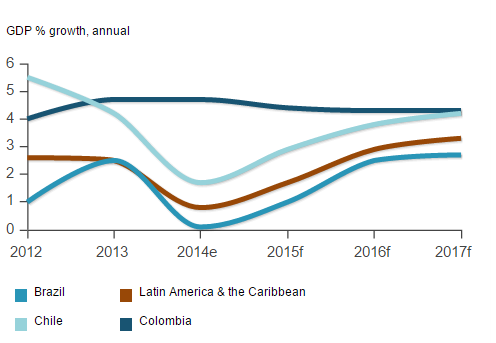

According to the World Bank, in 2014, the total Colombian population was an estimated 48.93 million.[16] The UNHCR assessed that in the first half of the year, more than 64,500 people were internally displaced, providing evidence of a growing humanitarian crisis despite the country’s current World Bank status as an upper middle-income economy (though this description is highly contested.[17] Colombia’s economy grew 6.4 percent in the first trimester of 2014 in comparison to 2013, and even if the GDP is expected to decrease slightly (from a 4.7 percent annual growth rate, until 2017, to 4.3 percent), it is still much higher than the average rate in the rest of Latin America (an estimated maximum of 3.3 percent until 2017).[18] Colombia’s economy is thriving beyond expectations compared to its regional neighbors, hence the growing number of displaced persons does not appear directly correlated to its overall economic situation. However, studies show that Colombia’s economic growth—and ability to weather the 2008 financial crisis—is directly linked to the illicit drug industry, which since the 1960s has had a severe negative influence on Colombia’s IDPs.[19]

As argued by the World Food Programme (WFP), all IDPs in Colombia belong to the 32.7 and 10.4 percent of the population living in poverty and extreme poverty in 2013. Meanwhile, statistics show that Colombians are becoming richer and that 1.5 million Colombians rose from poverty from 2013-2014.[20] However, as of today, “the average monthly income of an internally displaced family represents a little over 41 percent of the official minimum wage, equivalent to US$63 dollars,” which demonstrates that the distribution of wealth within Colombia is highly unequal and that a seemingly prosperous economy is not sufficiently benefiting IDPs.[21]

More than a Humanitarian Crisis?

The estimated abandoned or dispossessed land lost by IDPs is, until 2012, calculated to be as high as 6.8 million hectares.[22] After leaving especially rural areas, approximately 80 percent of IDPs migrate to big cities looking for two things: the security of being anonymous to avoid being targeted again; and access to public services that are inaccessible in their home municipalities.[23] In the outskirts of Bogotá, Las Americas (a south-west district) houses a substantial part of Bogotá’s IDPs, but they are also found in the districts of Suba (north) and Ciudad Bolívar (south-west). Women and children are particularly vulnerable segments of the IDP population who endure sexual exploitation, violence, and malnutrition. Furthermore, many adolescent girls find themselves forced into prostitution either by gangs or by choice simply to survive.[24]

Of the $63 USD that an average displaced family earn on a monthly basis, 58 percent is spent on food, six percent on health, and a mere three percent on education. This should not be an issue since President Santos, in 2012, declared primary and secondary education free of tuition through the Free Education Policy to benefit 8.6 million Colombian children.[25] Even if it appears adequate on the surface, the program is not sufficient to help the thousands of poor IDPs and their illiterate children. Many small NGOs help IDPs in Bogotá, and according to Victor Manuel Gallego Espinosa, the founder of the small NGO International Foundation for Fertile Ground (FUNTIFER, Fundación International Tierra Fértil), public schools in Bogotá do provide free education. However, the children still need school uniforms and books for their classes, which families often cannot afford. Many schools already are also overcrowded; forcing families to send their children further away to attend school, but transportation costs are too expensive.[26] Gallego Espinosa also explains how these struggles foment child labor, as children have to work to help their families with basic needs. The long-term benefits resulting from education cannot satisfy present necessities and attending school becomes too expensive for most IDPs in the first place.[27] In 2014, Colombia accounted for an estimated 1.1 million child workers, which has become a big issue for the Colombian government to solve, since child labor is illegal for all Colombians under the age of 15.[28]

Furthermore, many IDPs do not have the legal identification cards necessary to acquire health benefits, free education, or other services provided by the government. The UNHCR has discovered that the majority of IDPs experience severe psychological trauma from trying to cope with life in the big cities. They are not eligible for state services, live in poverty with a very low quality of life, cannot find jobs—especially on the formal labor market—since most are farmers and illiterate, and the barrios are haunted by violent gang activity—including those housing child gangs. Though more than 3 million children have received identification cards with help from the UNHRC so they can attend school and receive health care, there is still much to be done.[29]

According to the WHP, Colombia’s grave IDPs situation “hampers economic growth, threatens vital infrastructure, displaces populations, erodes social and cultural cohesion, and generates enormous fiscal costs.”[30] Colombia is already struggling to meet basic requirements of its citizens, and with over one tenth of the population being internally displaced, as well as an inequitable distribution of wealth, Colombia’s IDPs crisis only exacerbates the social, economic, and political challenges that the country already is facing.

The Government’s Response (or Lack Thereof)

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), “Colombia has one of the world’s oldest and most developed legal frameworks for responding to internal displacement,” but the Colombian government’s practical commitment to comply with the relevant legislation has been limited.[31] In 1997, Congress passed Law 387 making the government responsible for recognizing and assisting the millions of IDPs.[32] However, this law was poorly enforced. The 2005 Law of Peace and Justice, which focused on demobilizing armed groups and victims’ reparation, has been weakly applied and a predominant issue has been that most victims did not dare to come forth and claim their rights to land restitution; furthermore, the legal process became exceedingly time consuming. By 2008, only 24 IDPs had received damage payments.[33] In June 2011, Colombian President Santos passed, under domestic and international pressure, the Victims Law (or the Victim’s and Land Restitution bill):

“The Law deals broadly with the rights of all victims, including those who have been disappeared, murdered, or have suffered other serious violations of human rights, as well as specifically with the rights of those who have been displaced. All victims are granted rights to damages, restitution of prior living conditions, a range of social services, and special protections in legal proceedings.”[34]

The Constitutional Court introduced additional measures in 2013, including the IDPs’ right to emergency assistance.[35] A Brookings report shows that in Bogotá’s Suba and Ciudad Bolívar districts, governmental support to IDPs has been critical to secure their survival, and the initiatives taken under Santos have undoubtedly played an important role in this.[36] Santos is also co-responsible for the current peace talks conducted with FARC and ELN; one of the points on the shared agenda, still in negotiation, is how to compensate victims, including IDPs, from the 50-year long civil war.[37] The current government indeed seems more progressive in facing this humanitarian crisis than its predecessors, but a number of issues continue to overshadow any positive developments.

The implementation of laws affecting the well-being of IDP’s is fraught with administrative problems according to Gabriel Rojas Andrade of the Colombian NGO Consultancy on Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES, Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento).[38] Despite the enactment of Law 1190 in 2008 to establish the responsibility of Colombian local authorities regarding aid, such as emergency assistance, to IDPs, the authorities have struggled to meet the expectations as they are not only over-burdened, but suffer from corruption as well.[39] Furthermore, although the Victims Law was passed in 2011, only a small number of IDPs victims have received financial reparations and emergency assistance, which often has been delayed significantly. The government’s aid to vulnerable districts of Bogotá, such as Suba and Ciudad Bolívar, is short-term (medium-term at best) as well as being generally insufficient to meet the desperate needs of internally displaced families.[40] The Guardian ran a report in 2013 stating how state shortcomings continue to include:

“a crisis of protection, where IDPs pushing for rights to land restitution have been attacked, especially by paramilitaries in league with the new landowners; bureaucratic undercapacity worsened by the tangle of the various programmes; and the basic problem of implementing care and support in the middle of a conflict where the government has incomplete control of the country.”[41]

A serious example of governmental participation in violent acts, which break with the established protective laws for IDPs, took place in March 2011, just a few months before the passing of the Victims Law. The government sent police units to the district of Las Americas in Bogotá where they stormed, destroyed, and burned down the hand-constructed houses of 20-25 internally displaced families, which were illegally built on government land.[42] Thus, instead of protecting and aiding these families, which is the duty of the state, violence was used to evict them from otherwise unoccupied land, in which they only dwelled out of sheer necessity.

The most pressing issue with the government’s failure to address the crisis lies in the fact that most legislation and initiatives have been reactive instead of proactive. Victims’ compensation, including land restitution and recognition of IDPs’ rights, is certainly important, but a more effective approach would be to seek out and eradicate the underlying roots of Colombia’s crisis: specifically severe economic and social inequality.

“Colombia’s Invisible Crisis” – Maybe not so Invisible After All

The UNHCR has labelled IDPs as “Colombia’s Invisible Crisis.” But is it truly invisible? The government has openly admitted to the issue a long time ago, though adequate measures to halt the rise of more IDPs and successfully aid them have yet to be fully implemented. The peace talks are promising, and the violence of the civil war between Colombia’s armed forces and the insurgents is ebbing away, which should hinder the growth of IDPs to some extent, but drug trafficking and armed conflict continue to be key issues. In fact, the current humanitarian crisis does not appear invisible at all: with 5,840,590 IDPs—more than one tenth of Colombia’s entire population—the grave situation is no longer hidden. The crisis has been openly recognized by the government, numerous NGOs, churches, and political parties, which struggle to provide immediate relief and cover basic needs of the millions of IDPs scattered throughout Colombia. The situation is acknowledged internationally as well: the UNCHR budget to Colombia in 2015 is $31.6 million USD.[43] In 2012, the Colombian government put aside almost $8 million USD (COP1.9 billion Colombian Pesos), a 24 time funding increase since the beginning of the 2000s, and the 2011 Victims Law was passed with a budget of approximately $30 billion USD (COP54 billion Colombian Pesos) for the subsequent 10 years to improve the IDPs situation.[44] However, though these numbers may appear to be positive at a glance, Bogotá’s reactive actions are simply unsatisfactory to meet even the basic needs of almost 6 million IDPs—a number likely to rise.

Despite the budget of both the Colombian government and international organizations, such as the UNHCR, as well as a myriad of small local NGOs, Colombia’s crisis is threatening the country’s basic development and future social equality. The Santos Administration has taken big steps to address the situation, but so far, the current solutions have not brought on any long-term results, leaving much to be done. As stated by the Director of IDMC, Kate Halff, “[g]overnments are responsible for finding long-term solutions for their displaced citizens. However, these can only be realised when governments and the international community recognise that people forced from their homes require not only a humanitarian response at the height of a crisis, but sustained engagement until a lasting solution is achieved.”[45] Reaching a conclusion on how to compensate victims of the 50-year long war against FARC and ELN is one possible solution, and successfully limiting the drug industry’s reach in rural areas is another. In this spirit, it is clear that Colombia’s government is guilty of neglect and must take stronger proactive steps to practically meet the needs of the IDPs, especially by enforcing the laws and further advancing the political initiatives already underway. Bogotá has failed, so far, in reaching actual results. It is imperative that the Santos Administration places a high priority on collaboration with international agencies to find and implement long-term and effective solutions to this very visible crisis of internally displaced persons.

By: Louise Højen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured image by mariusz kluzniak. “Bogota city view hdr.” Taken on May 28, 2011. Taken from https://www.flickr.com/photos/39997856@N03/5893685534

References:

[1] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Colombia Overview.” Accessed Jan. 13, 2015: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e492ad6.html ; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”Colombia’s Invisible Crisis.” Accessed Jan. 21, 2015: http://unhcr.org/v-49b7ca8d2

[2] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Syrian Arab Republic Overview.” Accessed Jan. 14, 2015: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486a76.html

[3] Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Global Overview 2014. People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence,” May 2014.

[4] For a more extensive overview on the U.S. war on terror in Colombia: see Villar, Oliver & Drew Cottle. 2011. Cocaine, Death Squads and the War on Terror, U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia, New York: Monthly Review Press.

[5] Ibid ; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Colombia IDP Figures Analysis.” 2014. Accessed Jan. 14, 2015: http://www.internal-displacement.org/americas/colombia/figures-analysis

[6] Ibid.

[7] Beittel, June S. ”Colombia: Background, U.S. Relations, and Congressional Interest,” CSR Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service, Nov. 28, 2012.

[8] International Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Colombia IDP Figures Analysis.” Accessed Jan. 15, 2015: http://www.internal-displacement.org/americas/colombia/figures-analysis

[9] Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Global Overview 2014. People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence,” May 2014: 41-42.

[10] Villar, Oliver & Drew Cottle. 2011. Cocaine, Death Squads and the War on Terror, U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia, New York.

[11] Rosen, Jonathan D., 2013. “The War on Drugs in Colombia: A Current Account of U.S. Policy,” Perspectivas Internacionales, Vol. 9, No. 2: 68-69.

[12] Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. “Unseen Millions: The Catastrophe of Internal Displacement in Colombia Children and Adolescents at Risk,” 2002: 2.

[13] The Independent. ”Colombia faces $17bn laundry bill: Smuggling, drug trafficking and their profits are warping an entire economy,” Jun 2, 2013. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/colombia-faces-17bn-laundry-bill-smuggling-drug-trafficking-and-their-profits-are-warping-an-entire-economy-8640813.html

[14] Højen, Louise. “Opportunist or Visionary for Peace: Comprehending Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Nov. 3, 2014. Accessed Jan. 28, 2015: https://coha.org/opportunist-or-visionary-for-peace-comprehending-colombias-president-juan-manuel-santos/

[15] Forero, Juan. ”Colombia’s Government Seeks Bilateral Cease-Fire With FARC Rebels,” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 15, 2015. Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://www.wsj.com/articles/colombias-president-seeks-bilateral-cease-fire-with-farc-rebels-1421348131

[16] The World Bank, “Colombia.” Accessed Jan. 13, 2015: http://data.worldbank.org/country/colombia

[17] Ibid.

[18] The World Bank, “Global Economic Prospects.” Accessed Jan. 14, 2015: http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects/data?region=LAC

[19] Dalgaard, Bruce R. 1980. “Monetary Reform, 1923-30: A Prelude to Colombia’s Economic Development,” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 40, No. 1: 98-104 ; Villar, Oliver & Drew Cottle. 2011. Cocaine, Death Squads and the War on Terror, U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia, New York.

[20] This number is based on data from the Department of Statistics (DANE, Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística) and do not relate to the international poverty threshold, which is $1.25 USD per day according to the World Bank, though in Colombia, according to DANE, it is $3.50 USD (COP6,947 Colombian Pesos) ; World Food Programme. ”Colombia Overview.” Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://www.wfp.org/countries/colombia/overview ; Corbett, Craig. “Poverty levels continue to fall in Colombia: Government,” Colombia Reports, Sep. 17, 2014. Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://colombiareports.co/poverty-levels-continue-fall-colombia-according-government-stats/

[21] World Food Programme. ”Colombia Overview.” Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://www.wfp.org/countries/colombia/overview

[22] ABColombia “Colombia the Current Panorama: “Victims and Land Restitution Law 1448,” May 2012: 3.

[23] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”Surviving in the City: Bogota, Colombia.” Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://unhcr.org/v-4b260d656

[24] Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. “Unseen Millions: The Catastrophe of Internal Displacement in Colombia Children and Adolescents at Risk,” 2002: 1-2 ; Interview with Victor Manuel Gallego Espinosa on February 23, 2013 in the headquarters of Fundación Internacional Tierra Fértil in Las Palmitas, a small area in Las Americas, Bogotá. Visit FUNTIFER’s official website: http://funtifer.org/index.php/es/

[25] Alsema, Adriaan. ”Colombia implements free primary and secondary education,” Colombia Reports, Feb. 2, 2012. Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://colombiareports.co/colombia-implements-free-primary-and-secondary-education/

[26] Interview with Victor Manuel Gallego Espinosa on February 23, 2013 in the headquarters of Fundación Internacional Tierra Fértil in Las Palmitas, a small area in Las Americas, Bogotá. Visit FUNTIFER’s official website: http://funtifer.org/index.php/es/

[27] Ibid.

[28] El Ministro del Trabajo. “Rescate una niña o un niño del trabajo doméstico,” May 31, 2013. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://mintrabajo.gov.co/mayo-2013/1911-rescate-una-nina-o-un-nino-del-trabajo-domestico.html ; El Ministro del Trabajo. “Estados Unidos destaca avances de Colombia en lucha por erradicación del trabajo infantil,” Oct. 8, 2014. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.mintrabajo.gov.co/octubre/3883-estados-unidos-destaca-avances-de-colombia-en-lucha-por-erradicacion-del-trabajo-infantil.html

[29] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”Surviving in the City: Bogota, Colombia.” Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://unhcr.org/v-4b260d656

[30] World Food Programme. ”Colombia Overview.” Accessed Jan. 19, 2015: http://www.wfp.org/countries/colombia/overview

[31] Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Global Overview 2014. People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence,” May 2014: 42.

[32] Summers, Nicole. ”Colombia’s Victims’ Law,” Harvard Human Rights Journal, 2012, Vol. 25: 223.

[33] Ibid: 224.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Global Overview 2014. People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence,” May 2014: 42.

[36] Vidal López, Roberto Carlos, Clara Inés Atehortúa Arredondo and Jorge Salcedo. “The Effects of Internal Displacement on Host Communities: A Case Study of Suba and Ciudad Bolívar Localities in Bogotá, Colombia,” Brookings, Oct. 2011. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2011/10/host-communities-colombia-idp

[37] EFE. ”Gobierno ve con “moderado optimismo” fase decisiva del proceso de paz con Farc,” El Espectador, Jan. 19, 2015. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/paz/gobierno-ve-moderado-optimismo-fase-decisiva-del-proces-articulo-538824

[38] Anyadike, Obinna. ”Colombia’s internally displaced people caught in corridor of instability,” The Guardian, Aug. 12, 2013. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/aug/12/colombia-internally-displaced-people-instability

[39] Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Global Overview 2014. People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence,” May 2014: 42.

[40] Vidal López, Roberto Carlos, Clara Inés Atehortúa Arredondo and Jorge Salcedo. “The Effects of Internal Displacement on Host Communities: A Case Study of Suba and Ciudad Bolívar Localities in Bogotá, Colombia,” Brookings, Oct. 2011. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2011/10/host-communities-colombia-idp

[41] Anyadike, Obinna. ”Colombia’s internally displaced people caught in corridor of instability,” The Guardian, Aug. 12, 2013. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/aug/12/colombia-internally-displaced-people-instability

[42] Interview with Victor Manuel Gallego Espinosa on February 23, 2013 in the headquarters of Fundación Internacional Tierra Fértil in Las Palmitas, a small area in Las Americas, Bogotá. Visit FUNTIFER’s official website: http://funtifer.org/index.php/es/ ; Justice for Colombia. “Police Attack Displaced Families in Bogota,” Mar. 12, 2011. Accessed Jan. 20, 2015: http://www.justiceforcolombia.org/news/article/924/police-attack-displaced-families-in-bogota

[43] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). ”2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Colombia Overview.” Accessed Jan. 13, 2015: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e492ad6.html

[44] ABColombia “Colombia the Current Panorama: “Victims and Land Restitution Law 1448,” May 2012: 5.

[45] International Displacement Monitoring Centre. “Record-high 28.8 million internally displaced people worldwide in 2012; 5-fold jump in Syria.” April 29, 2013. Accessed Jan. 15, 2015: http://www.internal-displacement.org/blog/2013/record-high-28-8-million-internally-displaced-people-worldwide-in-2012-5-fold-jump-in-syria