Will Peronismo and not Kirchnerismo be the driving force in the upcoming legislative elections in Argentina?

By Eugenia Rosales Matienzo, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

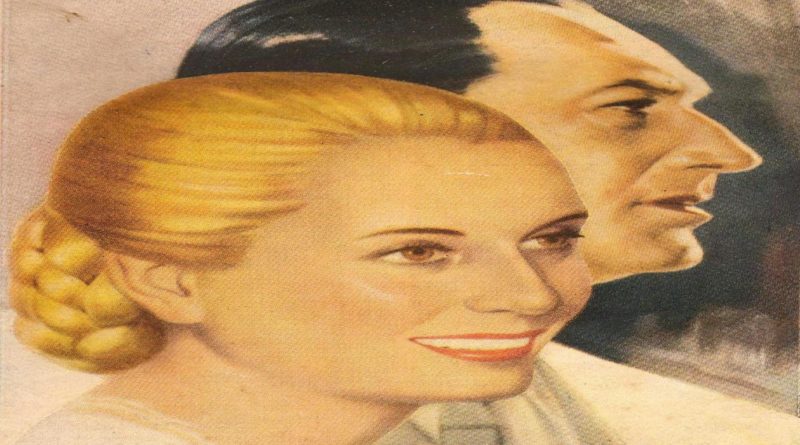

“I can not envision justicialismo without Perón” said Eva Perón more than sixty years ago.[i] Cristina Kirchner, who announced her candidacy for the upcoming legislative elections on October 22, has stirred Argentina’s political panorama over the past decade by straying from the structure of Perón’s political party, but never entirely disavowing its doctrines in the nation’s political life. This dissonance is in part due to the fact that the “Justicialist Party” refers to a political entity, while Peronismo is the consequence of political movement that arose from the gripping political sagas of Perón and Evita.

Cambiemos, a coalition led by President Mauricio Macri, has closed ranks and is now looking forward to the upcoming elections. In contrast, Peronismo was unable to settle on a single candidate after the internal primary elections that took place last August. Cristina Kirchner, Sergio Massa and Florencio Randazzo all identify with the Peronist ideology, but each is running as candidate for a different sub-coalition. The latter two have both been accused of collusion with the government; the lack of a united front by the Peronists divides support for the opposition force. It is widely believed that their chances of winning are slim, based on the modest share of votes they received in the previous election.

During a television interview on Crónica TV, former president Kirchner said her nomination was due to the fact that she is the Peronist leader with the best chance of winning the Buenos Aires province. “Peronismo is Unidad Ciudadana” (Unidad Ciudadana being the Kirchner coalition) the former president stated, explaining that “The Partido Justicialista is only an electoral instrument.”[ii] During the same interview, she again stated that she was Peronista, adding “I have always agreed with Peronismo. I was always Peronista and felt myself Peronista.”

Former president Juan Domingo Perón once said that “when you die for a noble and worthy cause, you will live forever in glory, which is where it is most beautiful to live.”[iii] Today there seems to be a competition over who is more Peronista ahead of the upcoming elections, with a win over Cambiemos depending on unity between Peronista voters. At the beginning of the “Kirchnerista period” back in 2003, just meters from the Arch of Triumph in Paris, then-First Lady Cristina Kirchner defiantly declared “I am not progre(sista), I am Peronista. The problem is that you do not understand.”[iv]

The former president has emphatically demonstrated during the election campaign period that she wants to be identified with Peronismo, and that she embodies the movement despite her critiques of the political party structure. “I am Peronista, I identify myself with Peronismo. I hate talking about Partido Justicialista because I define myself as Peronista,” said the former president.[v]

Nonetheless, in order to comprehend Peronismo, the movement must be separated from Justicialismo. Juan Domingo Perón said that “a political party without unity of action is an inorganic force, one that does not perform great works nor consolidates over time.” From 1946 to present, Peronismo candidates have won nine presidential elections.[vi] Peronismo is more than a political party; it is a movement that has to do with the doctrine of General Juan Domingo Perón. Justicialismo is merely the electoral instrument.

The government and the mass media supporting it have usually tried to separate the Peronismo from the former president, branding her politics “Kirchnerismo” to tie the image of Cristina and her late husband Néstor Kirchner to a period of government between 2003 – 2015 without political doctrine at all, as if they were a pair of outsiders.

Cristina has an undeniable past as a “militante” (political supporter) within the peronista movement and makes consistent mention of her militante youth, dating back to a period in which anyone with such a political ideology was persecuted. Since her childhood, her grandfather talked to her about Evita Perón. Her father was a bus driver. She was raised in a poor family that remained working class, and which benefited from the social policies of Perón. She likes to define Peronismo as a “plural and diverse political space,” more than just a left or right party.

There have not been more ideologically pro-Peronist presidents in Argentina than Néstor and Cristina Kirchner since Juan Domingo Perón himself. The Kirchners undertook actions to achieve economic independence such as the renegotiation of debt to the International Monetary Fund, the re-nationalization of the Aerolíneas Argentinas and the oil company YPF. Additionally, they implemented several socially inclusive policies such as the Asignación Universal por Hijo.

In the same manner, the main policy of Perón during his presidency was the introduction of import substitution industrialization. Perón achieved this by developing state industries, strengthening the labor movement under the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), enacting laws that regulated and improved the condition of workers, offering Argentine women the chance to vote by the Law of Universal Vote, and even eliminating fees on all levels of education, including university.

“Peronismo is not measured by how long someone has been peronista, it is measured by the facts, works and commitments that each person does,” said Cristina Kirchner in 2012,[vii] echoing the old sentiment of Perón, who once said: “the Peronista movement has revolutionized the forms and substance of national politics. It has always prioritized its three flags of the Argentina cause: social justice, economic independence and political sovereignty.[viii] On these facts, it could be argued that the Kirchners have also raised the “three Peronistas flags.”

“This is not a political force. It is not about our political party. What I want is that society and the people, rather than business groups, can once again become the owners of the state,” said Kirchner, days ago during a massive political rally in the city of Lanús.[ix] Her words were a candid reference to the opposition; namely, Mauricio Macri and his neoliberal policies favoring concentration of power in the hands of the few.

“I am Peronista, do not tell me that I am kirchnerista,” the senatorial candidate for Buenos Aires province declared this year during an interview with the newspaper El País of Spain, when asked by journalist Carlos Cué if kirchnerismo could go into decline if she lost the next legislative elections. “I always saw the denomination ‘kirchnerismo’ as a way to bring us Peronistas down,” she added.[x]

In the middle of a fragmented period for the Peronistas, the president of the National Justicialist Party, José Luis Gioja, called for the people to vote for the former president in the upcoming elections. He did so through an “Open Letter to the Peronista people” in which he said that Unidad Ciudadana “is the strongest political label inside the peronista movement to regain hope and stop the economic adjustment” by Macri’s administration.

In the letter Gioja claims: “Let’s allow ourselves to focus on what matters: Peronismo has to win in the October elections to defend the people from what will be a brutal adjustment by Macri if he win the elections.”[xi]

Perón always insisted on the popular sense of Peronista politics. For him, “Peronismo is essentially popular; a Peronista works for the whole movement; and a government without doctrine is like ‘a body without a soul’, so a movement- like Peronismo- has its own political, economic and social doctrine.”[xii]

Cristina Kirchner’s last campaign rally before the elections will take place October 16, just a few hours before celebrating the anniversary of “Día de la Lealtad Peronista” (Peronist Loyalty day), and she has called for thousands of Peronistas from all sectors to attend the rally at Racing Club de Avellaneda, the stadium of the soccer club of which both Néstor Kirchner and Juan Perón were avid fans.

By Eugenia Rosales Matienzo, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Tomas Bayas, Arianna La Marca, Joride Conde, and Gavin Allman, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Image: Juan y Eva Perón Taken From: Wikimedia

[i] Mundo Peronista magazine, 2nd edition -pag. 3– (August, 1951)

[ii] Cristina Kirchner during a Crónica TV’s interview on TV channel with the same name on September 28, 2017.

[iii] Juan Domingo Perón, September 13, 1950.

[iv] Cristina Kirchner during a meeting in Paris as First Lady in November 2003.

[v] Cristina Kirchner during a press conference at Casa Rosada on October 17, 2012.

[vi] Juan Domingo Perón (1 946 – 1951); Juan Domingo Perón (1951 – 1955); Héctor Cámpora (1973 – 1973); Juan Domingo Perón (1973 – 1974); Carlos Saúl Menem (1989 – 1995); Carlos Saúl Menem (1995 – 1999); Néstor Kirchner (2003 -2007); Cristina Kirchner (2007 – 2011); Cristina Kirchner (2011-2015).

[vii] Cristina Kirchner during a press conference at Casa Rosada on October 17, 2012.

[viii] Juan Domingo Perón wrote for the magazine Mundo Peronista 2nd edition (August, 1951).

[ix] Cristina Kirchner during a campaign rally in the city of Lanus (Oct. 3, 2017).

[x] Interview Cristina Kirchner to the newspaper El País of Spain (28 September 2017)

[xi] Open letter to the Peronista people by President of the Justicialist Party (September 2017).

[xii] Mundo Peronista magazine, 1st edition (July, 1951).