Understanding the Petrobras Scandal

By Esther Fuentes, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Since March 2014, Brazil has been shaken by the revelations from Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash), which exposed the Petrobras’ scheme as the largest corruption scandal ever reported in the country. On March 2016, two years after the beginning of investigations, Lava Jato entered a new phase, focusing on the alleged involvement of Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, the nation’s president from 2003 through 2010. Brazil’s political world, already strained by the investigations of office holders, became even more tense after Senator Delcídio do Amaral, a former Senate leader for the Workers Party (PT), was arrested in November 2015 and in a plea bargain arrangement began citing colleagues both from the government as well as from the opposition for alleged involvement in the corruption scheme. Political tension continued to rise in Brazil after the mass protests on March 13 demanded for President Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment and more recently, when Lula, her predecessor, was nominated for a position as a Minister in Rousseff’s administration.

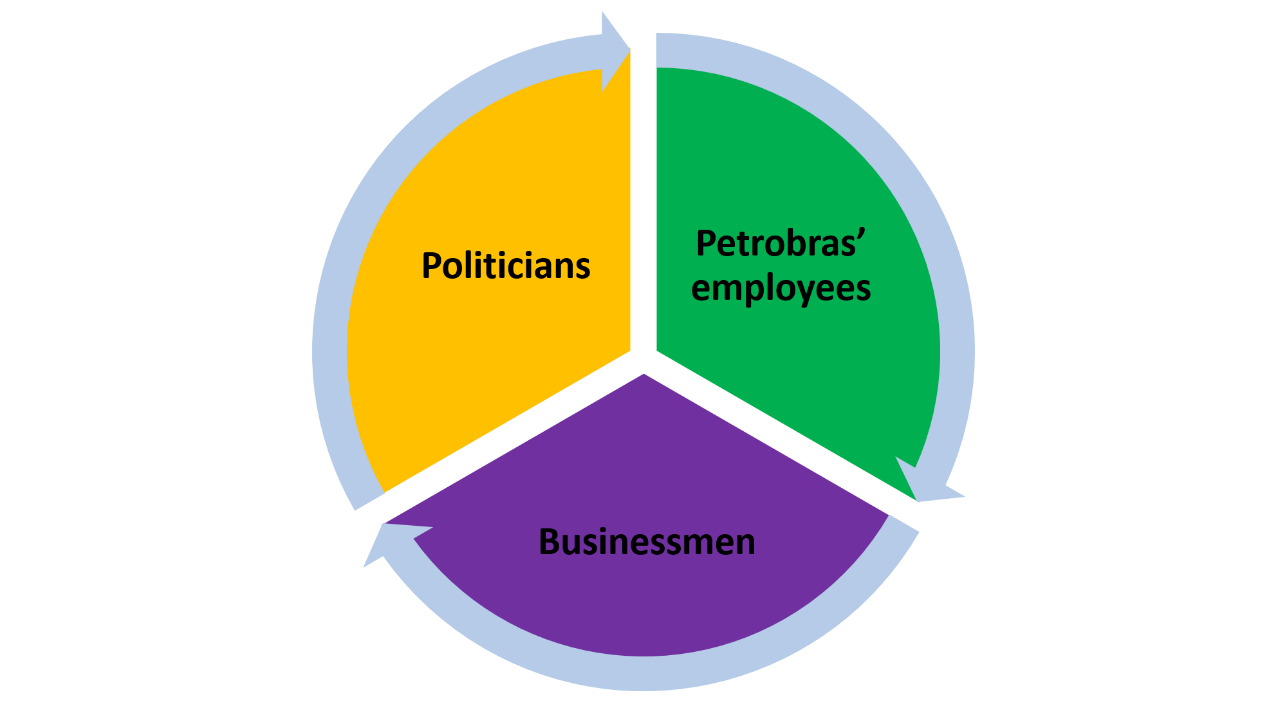

The Lava Jato (Car Wash) drama has starred national politicians caught up in its spotlight, but the corruption under investigation began and continued with two other sectors: Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., Brazil’s semi-public national oil company, and the collection of mostly large firms that do business with it. The Petrobras scandal was an enormous matrix of secretive schemes in which these three sectors have intertwined over the years in illicitly channeling billions of dollars. It is important to analyze the entire picture of actors involved in the scandal.

Image 1: Sectors involved in Petrobras’ scandal

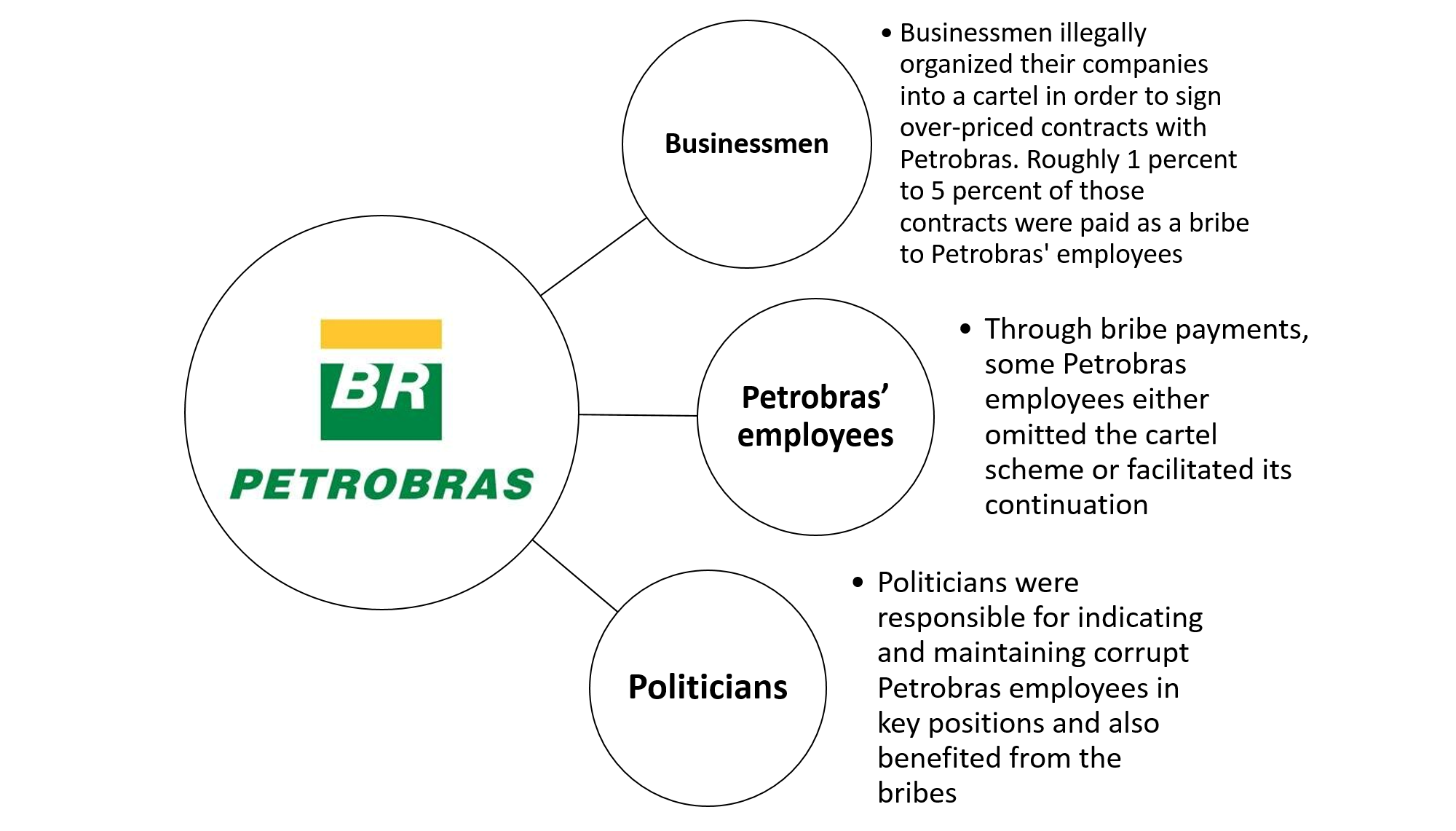

Image 2: How Petrobras’ scheme worked

Petrobras, as Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. is known, is Brazil’s most important company. Sixty-four percent government-owned[i], it explores for and extracts petroleum and natural gas in Brazil and abroad, refines them into products, which it transports and markets, produces biofuels, and distributes oil products and renewable energy fuels, among other activities[ii]. The firm’s businesses include thermoelectric, ethanol and biodiesel operations and gas pipelines and fertilizer factories.[iii] In 2014 Petrobras estimated that oil and natural gas constituted 13 percent of Brazil’s GDP, crediting itself for most of that economic sector.[iv] Petrobras is also a major sponsor of sports[v], entertainment and cultural events.[vi] Construction and other contracts for Petrobras business run into the billions of dollars annually, and it is within this context that the scandal began.

The starting point for such a scheme was in 2004,[vii] as discovered so far through the investigations carried out in Operation Lava Jato, when large constructions firms, known in Brazil as empreiteiras, organized an illegal cartel with the aim of landing overpriced contracts with Petrobras for private benefits, what caused serious damage to Petrobras’ bottom line. To maintain the cartel and guarantee that only member companies could sign on to Petrobras’ contracts, the empreiteiras operatives bribed Petrobras’ employees.[viii] Most employees who were offered bribes had important positions in the firm or served on its board of directors; others were subordinates.

The corruption entered the political sphere through the involvement of public office holders who got favored individuals’ jobs in Petrobras, sometimes in key positions, and received money in return. Political influence became heaviest in the giant company’s supply, services and international units.[ix] Bribe money was not paid directly, but rather was channeled discreetly through black-market financial operators known as doleiros[x] (a term related to the U.S. dollars they used). Doleiros would receive the money from the empreiteiras businessmen through offshore companies and funnel it to the intended recipients.[xi] The intricate and sophisticated scheme involved transactions inside Brazil and abroad, involving foreign citizens and Brazilian nationals, foreign and Brazilian companies.[xii] Among the companies through which intermediaries laundered the money are Constructora Internacional del Sur S.A and Deep Sea Oil Corp, which operate internationally.[xiii] Operation Lava Jato reveals new updates daily. Although news mainly concerns politicians targeted for their involvement, businessmen[xiv] and Petrobras’ employees[xv] have already been convicted for theirs acts.

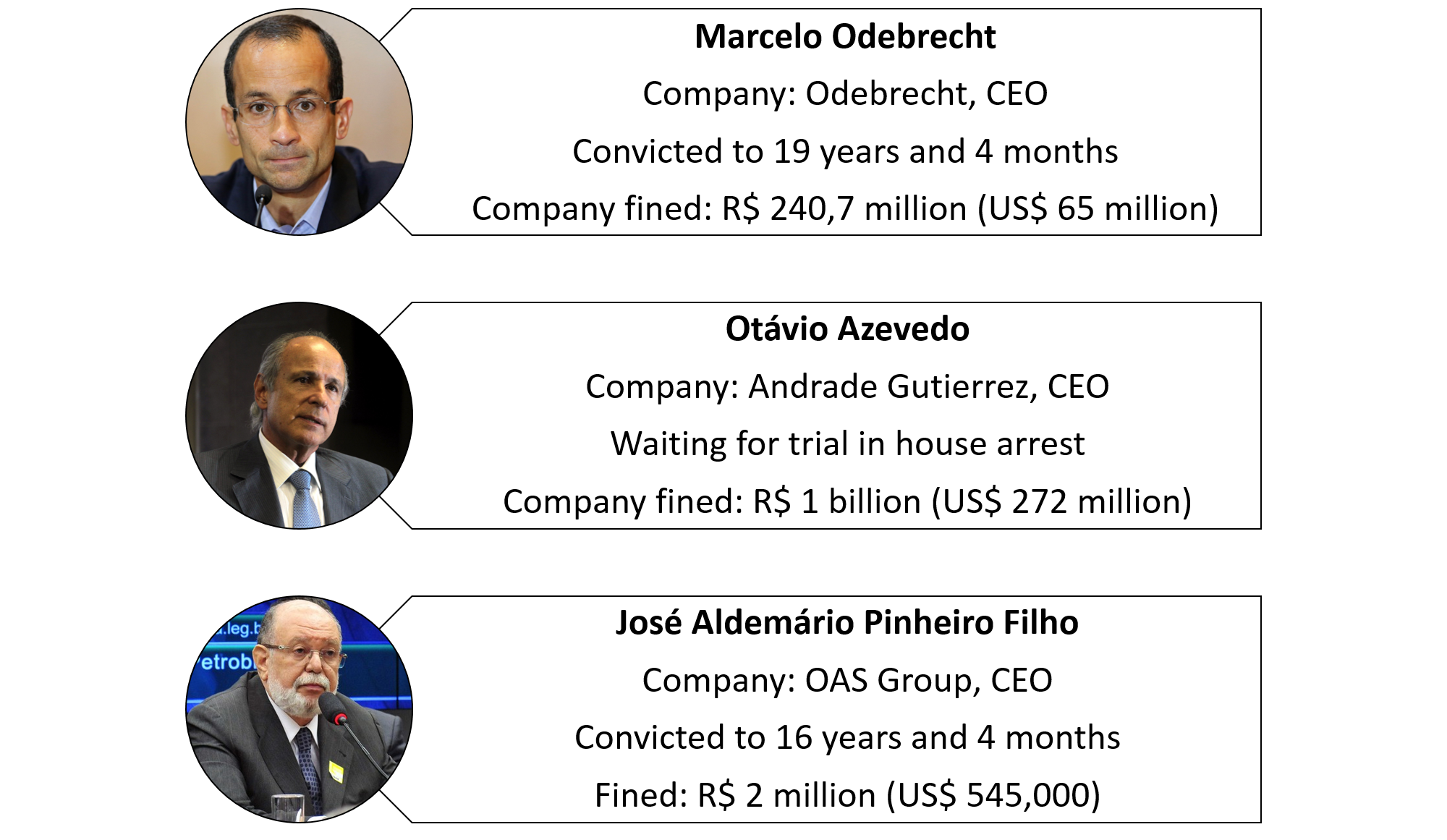

Image 3: Businessmen involved in Petrobras’ scheme

Their convictions were easier for prosecutors to obtain than those of suspects holding high political office in part because the latter enjoy a privileged status (foro provilegiado). As previously explained in a COHA article,[xvi] privileged forum is a type of status given to some high public officials that only allows the Brazilian Supreme Court to prosecute them. So Federal Judge Sergio Moro, who is leading the Lava Jato prosecution, has legal authority to prosecute businessmen and Petrobras’ employees but not politicians with privileged status. According to Deltan Dallagnol, coordinator of a taskforce for Operation Lava Jato, this factor has caused interruptions and delays in the prosecutions of allegedly corrupt public officials.[xvii]

Convictions of important businessmen include that of Marcelo Odebrecht, CEO of Norberto Odebrecht, Brazil’s largest construction firm. Along with other businessmen and Petrobras’ employees, he was convicted by Judge Moro on March 8, 2016.[xviii] Like the corruption scheme itself, the Lavo Jato investigations began with Petrobras and its contractors and led to the political sector.

New revelations can come forward daily. Odebrecht and his convicted employees recently negotiated a plea-bargaining agreement to reduce their punishment.[xix] Because of the interlinked nature of the scheme, developments are sure to emerge and continue to affect Brazil’s already unstable national political environment — already coping with severe economic recession and its hosting of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games this August in Rio de Janeiro.

By Esther Fuentes, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured Photo: Petrobras Scandal. Taken from Youtube.

[i] “Fatia de controle do governo na Petrobras sobe para 64%”. G1. September 28, 2010. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://g1.globo.com/economia-e-negocios/noticia/2010/09/fatia-de-controle-do-governo-na-petrobras-sobe-para-64.html.

[ii] “Perfil”. Petrobras. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.petrobras.com.br/pt/quem-somos/perfil/.

[iii] “Principais Operações”. Petrobras. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.petrobras.com.br/pt/nossas-atividades/principais-operacoes/.

[iv] Nunes, Fernanda. “Com investimentos da Petrobras, petróleo avança para 13% do PIB brasileiro”. Estadão. June 17, 2014. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias/mercados,com-investimentos-da-petrobras-petroleo-avanca-para-13-do-pib-brasileiro,1513541.

[v] “Atuação no esporte”. Petrobras. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.petrobras.com.br/pt/sociedade-e-meio-ambiente/sociedade/atuacao-no-esporte/.

[vi] “Projetos patrocinados”. Petrobras. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://www.hotsitespetrobras.com.br/cultura/projetos.

[vii] Macedo, Fausto, Fernanda Yoneya. “Petrobras é o segundo maior escândalo de corrupção do mundo, aponta Transparência Internacional”. Estadão. February 10, 2016. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/fausto-macedo/petrobras-e-o-segundo-maior-escandalo-de-corrupcao-do-mundo-aponta-transparencia-internacional/.

[viii] “Caso Lava Jato: Entenda o Caso”. MPF. Accessed March 18, 2016. http://lavajato.mpf.mp.br/entenda-o-caso.

[ix] Ibid

[x] Ibid

[xi] Justi, Adriana, Bibiana Dionísio. “Justiça Federal condena Marcelo Odebrecht em ação da Lava Jato”. G1. March 8, 2016. Accessed March 9, 2016. http://g1.globo.com/pr/parana/noticia/2016/03/justica-federal-condena-marcelo-odebrecht-em-acao-da-lava-jato.html.

[xii] Brandt, Ricardo, Fausto Macedo. “Lava Jato investiga elo de offshores com Odebrecht e Andrade Gutierrez”. Senado. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/512353/noticia.html?sequence=1.

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv] Coutinho Mateus, Fausto Macedo, Julia Affonso. “Em um ano, Moro condena empreiteiros de esquema na Petrobras”. Estadão. December 15, 2015. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/fausto-macedo/em-um-ano-moro-condena-empreiteiros-de-esquema-na-petrobras/.

[xv] Dionísio, Bibiana, Adriana Justi. “Justiça condenada Zelada, ex-diretor da Petrobras, a 12 anos de prisão”. G1. February 01, 2016. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://g1.globo.com/pr/parana/noticia/2016/02/justica-condena-zelada-ex-diretor-da-petrobras-doze-anos-de-prisao.html.

[xvi] Fuentes, Esther, Rachael Hilderbrand. “Potential Legal Immunity in Corruption Charges Against Brazil’s Former President”. Council on Hemispheric Affairs. March 18, 2016. Accessed March 19, 2016. https://coha.org/potential-legal-immunity-in-corruption-charges-against-brazils-former-president/.

[xvii] Vieira, Isabela. “Procurador da Lava Jato critica foro privilegiado, que beneficia 22 mil pessoas”. Agência Brasil. November 25, 2015. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/politica/noticia/2015-11/procurador-da-lava-jato-critica-foro-privilegiado-que-beneficia-22-mil.

[xviii] Bergamo, Mônica, Graciliano Rocha. “Marcelo Odebrecht é condenado a 19 anos e 4 meses de prisão”. Folha de S. Paulo. March 08, 2016. Accessed March 09, 2016. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2016/03/1747575-marcelo-odebrecht-e-condenado-a-19-anos-e-4-meses-de-prisao.shtml.

[xix] Bretas, Valéria. “Secretária da Odebrecht negocia acordo de delação premiada”. Exame. March 08, 2016. Accessed March 24, 2016. http://exame.abril.com.br/brasil/noticias/secretaria-da-odebrecht-negocia-acordo-de-delacao-premiada.