Puerto Rico Knocks on the Door of Statehood

On Tuesday, November 6, while the world turned their eyes to America’s presidential election, Puerto Ricans were simultaneously holding both a referendum on its political status as well as its own gubernatorial election. While Governor Luis Fortuño, who has persistently shown his support for Puerto Rico’s estatidad (annexation to the United States), failed to win another term, the electorate appears to have provided support for a move towards statehood. These results provide a muddled message for Puerto Ricans regarding their future status.

In 1898, when the former Spanish Empire lost the Caribbean island at the end of the Spanish-American War, the Puerto Rican-described “island of enchantment” came under U.S. control, and automatically received the designation of a Free Associated State. By 1917, the United States had granted a limited citizenship to Puerto Ricans via the Jones Act. Despite not paying U.S. federal income taxes on wages earned in Puerto Rico, citizens of Puerto Rico were subject to the U.S. selective service, also known as the compulsory enlistment program for the military. This rule explains why thousands of Puerto Ricans sacrificed their lives to fight for America during the Second World War, Korean War, and Vietnam War. However, Puerto Ricans’ political rights still remain ambiguous and limited, given that the island has continuously been denied full representation in Congress; moreover, Puerto Ricans have never had the right to vote for U.S. presidential candidates in the General Election.

In 1952 the Caribbean island achieved a certain level of internal and economic autonomy when it become a “non-sovereign U.S. Insular Area”, also known as a commonwealth. Under the island´s current status, the Puerto Rican government has been able to improve its administrative practices, transforming the country into one of the most dynamic economies in the Caribbean. However, Puerto Rico still lags behind other sectors of the United States in many key economic indicators.[1] At the same time, nearly half of Puerto Rico’s population lives in poverty, while the price of food and housing is higher than the U.S. national average. [2]

For Puerto Ricans, this kind of referendum has become something of a political routine. Over the past 45 years, the government has celebrated four non-binding referenda on the island’s political status. Although a sizable majority voted against Puerto Rico’s annexation in 1967,1993, and 1998, this time around, citizens appear to have voted in favor of changing their island’s current political status. However, many voters were still critical of the way in which the two-question referendum was designed. The first question asked the island voter whether he or she agreed or disagreed with maintaining the current political relationship with the United States. The second question allowed the electorate to choose, independently of the first question response, among three status alternatives for the island: statehood, independence, or to become a sovereign U.S. insular area (as opposed to its current status, which was not enunciated as one of the alternatives).

The controversy surrounding the construction of the second question may be related to the fact that the governing Partido Nuevo Progresista (PNP) unilaterally defined alternatives for the second question. Former Governor Aníbal Acevedo Viláa, and newly elected governor Alejandro García Padilla, have both asserted that the second question contained a striking bias because it did not incorporate the current status. For this reason, García Padilla’s party, the Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) called upon its supporters to mark “yes” for the first question, and then leave the second question blank.[3]

According to the Comisión Estatal de Elecciones, roughly two million of the island’s 3.7 million inhabitants cast their vote in both the referendum and the gubernatorial election. On the first question regarding association with the United States, roughly 53 percent voted to change the island’s political relationship with the United States, though it is hard to determine if this tally represents a true mandate. The problem comes from attempting to accurately poll opinions when the directions present the options point-blank, as black and white, between statehood and independence.[4]

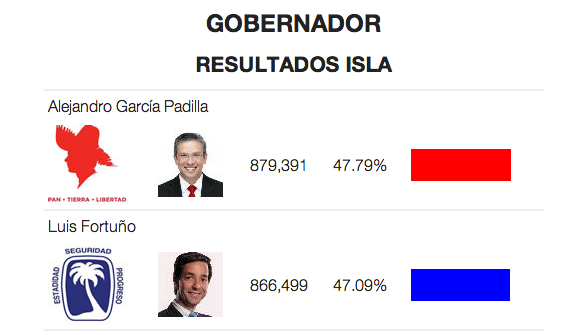

On the second question, 62.81 percent of the electorate chose statehood, 32.25 percent favored “sovereign free association,” and 4.93 percent elected independence. However, more than 400,000 voters did not bother to answer the second question, which means that neither option reached a majority.[5] On November 6, PNP candidate and governor Luis Fortuño (47.19 percent) lost by less than one percentage point against opponent Alejandro García Padilla (47.81 percent) in a very contested election. As a result, many in Puerto Rico perceive the PNP victory in the referendum to be somewhat diminished by the fact that García Padilla, who is an outspoken defender of Puerto Rico´s current political status, won the gubernatorial election.

Nonetheless, the Puerto Rican Resident Commissioner (or Congressional representative), Pedro Pierluisi, a member of PNP, was reelected on November 6. This means that along with the ballot victory, the PNP still has a member in a key position- a reality that future governor García Padilla cannot dismiss. It remains to be seen what President Barack Obama’s reaction to Puerto Rico’s referendum result will be, if he responds at all. Last year during a visit to San Juan, the American leader offered his conditional support to the will of Puerto Ricans if there were to be a clear majority. Although Puerto Ricans have voiced their disapproval of the current political status this time around, they still seem to feel unclear about the direction the island should take as they failed to vote for an alternative on the second question. The Sovereign Union Movement, a new party by the Puerto Rican Academia, seems to be a pertinent option to generate a discussion on defining a political status that would provide the island with the most beneficial degree of autonomy.

Separately, the Caribbean island’s economy is of utmost concern when dealing with Puerto Rico’s political fate. According to Bloomberg News, Puerto Rico’s debt has swollen to nearly $67 billion USD from a mere $30 billion USD a decade ago (or 89 percent of its GDP, the largest of any U.S. state or territory), while unemployment has risen to more than 13 per cent. [6] If Puerto Rico, whose GDP per capita is $23,380 USD, is to become the 51st state of the United States, the island will become the poorest state in the Union, falling behind Mississippi, whose GDP per capita stands at $32,967 USD. Under the current pressure to overcome the end of the year’s massive triggering of sequestration and tax increases (the “fiscal cliff”), prospects look dim for a Congress that might be unwilling to welcome the Puerto Rican de facto colony with open arms, and would be more likely to stick with status quo. On the other hand, Puerto Ricans seeking the island’s long-awaited independence would need to put all of their efforts into convincing many of their skeptical fellow countrymen, who believe that Puerto Rico’s association with the United States serves as the defining factor that distinguishes the island from its Caribbean brethren.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated

Sources:

[1] Angel Carrión, “Yet another Political Status in Puerto Rico”, http://globalvoicesonline.org/2012/11/07/yet-another-political-status-referendum-in-puerto-rico/

[2] Jack Zahora, “Puerto Ricans press US for state status”, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2012/11/20121111142129195368.html.

[3] Angel Carrión, “Yet another Political Status in Puerto Rico”, http://globalvoicesonline.org/2012/11/07/yet-another-political-status-referendum-in-puerto-rico/

[4] “No majority opinion in Puerto Rico”, http://www.bloggingsbyboz.com.

[5] “Surge en Puerto Rico Movimiento Soberanista para lograr descolonización”, http://www.telesurtv.net/articulos/2012/11/07/surge-en-puerto-rico-movimiento-soberanista-para-lograr-descolonizacion-3658.html.

[6] Michelle Kaske, “Puerto Rico Debt Extends Slump Before Governor Vote: Muni Credit”, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-12/puerto-rico-debt-extends-slump-before-governor-vote-muni-credit.html.

See Also: