Checkbook Diplomacy: The Economics of Sino-Caribbean Relations

This past June, Chinese President Xi Jinping traveled to the Caribbean in order to deepen bilateral relations with several countries and to dole out generous checks and loans. [1] Beijing’s “checkbook diplomacy” affects relations not solely between the Caribbean and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), but also between that region and the Republic of China (Taiwan). Unsurprisingly, Taiwan is affected the most by Beijing’s growing influence throughout the Caribbean because the PRC is trying to shrink Taipei’s network of allies. Furthermore, because the Caribbean is considered to be a strategic region by the United States, Washington will also have to address the challenges of Beijing’s increasing presence in the region.

The practice of handing out checks has been called “checkbook diplomacy,” a process where a government provides loans and financial gifts to obtain diplomatic favors from other nations. The current situation of the Caribbean region, in which over the past decades several governments have switched from having relations with Taipei to having them with Beijing, is an example of the success of China’s checkbook diplomacy.

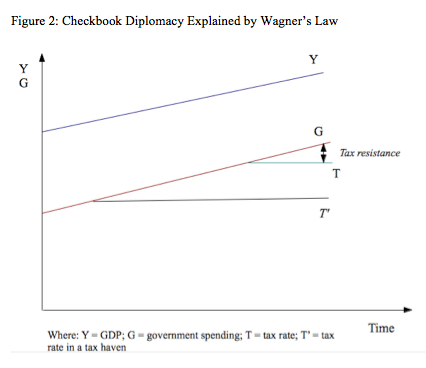

One of the most important features of the Caribbean islands is the presence of offshore financial services, which have been in place since the 1960s; in other words, most of the islands are tax havens. [2] The term “tax haven” has many definitions and there is little consensus. Generally, tax havens, also called tax shelters or offshore financial centers (OFC), are known to provide a competitive tax structure that allows foreign individuals and societies to avoid the restrictions of their own tax system. Hence, the tax havens have two integral features: (1) secrecy and (2) a low or nonexistent tax rate. Economist Adolf Wagner’s theory, which states that a country’s public spending increases as it develops, may explain the success of Beijing’s checkbook diplomacy in the Caribbean. [3]

What is at Stake for Beijing?

The intensification of Sino-Caribbean relations started in the 1970s and has accelerated since the 1990s. Beijing has two economic and political goals: (1) to secure access to raw materials (such as oil, bauxite, and sugar) and to the Panama Canal; and (2) to diplomatically isolate Taipei. Out of Taiwan’s 26 allies across the globe, 11 of them are located in the Caribbean basin: Belize, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. [4] Ever since the Republic of China politically separated from mainland China in 1949, Beijing has been irredentist and therefore has carried out several strategies to attempt to reincorporate Taiwan.

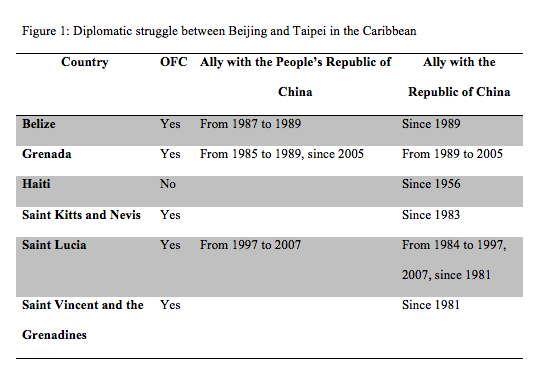

By resorting to checkbook diplomacy in the Caribbean, the PRC aims to further challenge Taiwan’s independence and to isolate it from the international community. Ultimately, the PRC uses checkbook diplomacy to appeal to Taiwan’s allies. The PRC offers funding to Caribbean states in exchange for diplomatic recognition of Beijing and a severance of relations with Taipei. The shifting alliances of the Caribbean states are summed up in the table below. The most obvious feature of the table is the struggle between the Republic of China and the PRC, particularly over Grenada and Saint Lucia, as both Taipei and Beijing use checkbook diplomacy to act on the network of alliances.

Thus, it is clear that checkbook diplomacy does not definitively guarantee success because it can be easily challenged by other nations. Figure 1 highlights some of Taipei’s allies that are the priority targets of Beijing’s checkbook diplomacy (Belize, Haiti, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines).

Wagner studied the way in which public spending can be used to improve the economic situation of a country when it reaches a certain level of development. The more developed a nation becomes (reflected in its Gross Domestic Product, denoted as Y on the graph), the higher public spending (denoted as G) will be. However, after a certain point, the government has a limited ability to tax its citizens. This relationship is described in Figure 2. After a certain times, the population is reluctant to bear more taxes, a phenomenon known as tax resistance, shown as the difference between lines G and T (where T represents taxes, a relatively flat line). In the graph, Τ represents a low or nonexistent tax rate, a constitutive feature of tax havens. Countries that serve as tax havens have limited taxation, and thus the difference between the lines G and T is greater.

Because governments of tax haven countries choose to have this kind of tax rate, their capacity to tax their own citizens and the businesses located in their territory is very weak. As a result, the governments of tax haven countries have little choice but to use public deficit spending. The capacity of tax haven countries in the Caribbean to accumulate debt is limited when compared with other wealthier countries, such as the United States and several nations in Europe. Indeed, having a smaller economy may thwart the capacity for a country to obtain loans and funds, because investors may doubt the country’s ability of pay back their loans and prefer to invest in economies that are attractive.

Nevertheless, Caribbean countries are committed to spending on social and economic development, in order to remain competitive and appealing to foreign investment. Offshore financial services are the main sector of economic activity in Caribbean tax havens but are not reliable in the long term, given the possible migration of capital to other, more attractive regions (i.e. the United States). However, the offshore financial sector can have positive externalities for the local population, regarding employment and the funding of some welfare policies through rare taxes on companies and assets. As a consequence, tax haven countries need to avoid the loss of their offshore financial sector. In order to avoid this demise, they must improve some offshore laws to be more competitive in attracting clients. Nevertheless, another country may be more appealing or the regional context of the Caribbean basin may be disadvantageous (due to insecurity, riots, etc.), and as a consequence, the offshore financial industry may migrate to other countries very quickly.

One of the main features of the financial industry is its ability to move swiftly; thus, a country should not rely on it entirely. The tourism industry has strong potential in the Caribbean islands because of the region’s appealing natural environment, which could efficiently palliate a loss within the financial industry in terms of employment and personal services. The development of the tourism industry requires investments in infrastructure, but such public initiatives are obstructed by the incapacity of the state to take advantage of taxation or public spending, following Wagner’s law.

What follows are examples of PRC funding in the Caribbean in the framework of checkbook diplomacy:

- 1997: Bahamas – The PRC donated $14 million USD to build docks and three resorts at Nassau. [5]

- 1997: Saint Lucia – The PRC provided $15 million USD for the construction of a cricket stadium and $10 million USD to build a psychiatric hospital. (However, Castries, the capital of Saint Lucia, switched to recognizing Taipei, which provided more generous loans). [6]

- 2007: Costa Rica – The PRC gave $300 million USD so that the nation could lower its national debt. [7]

- 2011: Bahamas – The PRC donated $3.4 billion USD for a resort. [8]

The PRC’s checkbook diplomacy clearly helps fund needed infrastructure, such as hospitals, schools, and clinics. Hence, tax haven countries do not have to rely on public spending (G) and thus taxation (T) to fund such projects. The Caribbean’s difficulty regarding budget management partially explains the success of Beijing’s checks to Caribbean countries, which need to raise funds to develop their tourism potential and to satisfy a certain quality of life for their populations.

The behavior of these countries demonstrates that checkbook diplomacy can be effective in the Caribbean basin. As tax havens, most Caribbean countries have a limited use of taxation and are unable to raise sufficient funds for public spending to lead their economies towards development. Thus, Wagner’s law adequately explains this phenomenon and its success regarding characteristics of the Caribbean.

Challenges in an Unusual Diplomatic Struggle

In addition to financial gifts, a growing Chinese and Taiwanese presence in the region provides Caribbean countries the opportunity to diversify their diplomatic networks, which are currently monopolized mainly by Western countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Netherlands) and also by Latin American ones (the members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America). In the case of the United States, Washington did not engage with Caribbean countries at any significant level to counteract the PRC. Washington started a process to increase its cooperation in the Caribbean during Barack Obama’s presidency; for example, Joe Biden visited Trinidad and Tobago in May 2013. [9] However, unlike the United States, Beijing does not interfere in the internal affairs of Caribbean countries, nor does it try to challenge the sovereignty of those nations. This attitude is likely to be more appreciated by the countries than that of the United Nations.

The United States undoubtedly remains the main power in the Caribbean. Still, it is appropriate to question U.S. behavior towards the PRC. Since the PRC’s government has different priorities and interests than those of the United States (for example Washington is, arguably, more interested than Beijing in protecting human rights and democracy in the Caribbean), Washington may decide to adjust its policies to challenge Beijing’s growing influence in that region, which has been historically regarded as “Washington’s backyard.” The United States has traditionally used hard power policies, but the country may be ready to implement checkbook diplomacy in order to challenge the PRC in the Caribbean. The Caribbean basin is a strategic area for the United States due to economic interests and security concerns, particularly as the region has become a corridor for drug trafficking from South America, as well as other crimes like human trafficking. Washington will want to continue to ensure that its influence and security interests in the region are not being jeopardized. Despite an absence of official recognition, the United States has trade relations with Taiwan and tries to keep its ties with the island in good shape. [10] As a consequence, Washington may want to help Taiwan maintain enough allies in the Caribbean.

Concluding Remarks

The PRC’s practice of checkbook diplomacy has proven to be successful in the Caribbean. The application of Wagner’s theory demonstrates how this success is due to both the incapacity of Caribbean countries to use traditional means of funding, such as public spending and taxation, and the desire of these countries to ensure growth and development. Two issues are now of central importance for Washington: (1) the challenge of U.S. hegemony in the Caribbean and (2) the diplomatic strangulation of Taiwan, a country with which it has unofficial relations. The lack of significant initiatives from Washington in the past years led to the initiatives of Taiwan and the PRC in the Caribbean. This diplomatic and financial rapprochement is not only changing the relationship between the two Asian countries, but also is affecting the ties between the United States and the Caribbean. In addition, interestingly enough, the Caribbean countries seem to not consider the political consequences of their shifting alliances. They seem to make their decisions by solely focusing on short-term economic opportunities, which could have dire consequences for them in the future.

Elise Lefeuvre, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

[1] AFP. “Le président chinois Xi rencontre les dirigeants de la Caraïbe” (The Chinese president is meeting the Caribbean leaders), Les Echos, 06 February 2013, http://www.lesechos.fr/entreprises-secteurs/service-distribution/actu/afp-00525494-le-president-chinois-xi-rencontre-les-dirigeants-des-caraibes-571400.php.

[2] Alan Markoff, “The Cayman Islands Financial Centre: History and Overview,” Cayman Financial Review, 2011, http://www.compasscayman.com/cfr/story.aspx?id=1360.

[3] Adolf Wagner, Lehrbuch der politischen Ökonomie, 1872.

[4] John Peter Pham, “China’s Strategic Penetration of Latin America: What it Means for U.S. Interests,” American Foreign Policy Interests 32.6 (2010).

[5] Jerome McElroy and Wenwen Bai, “The Political Economy of China’s Incursion into the Caribbean and Pacific,” Island Studies Journal 3.2 (2008).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tiffany Lam, “China Heads to the Bahamas to Build Massive US$3.4 Billion Resort”, CNN, 22 February 2011, http://travel.cnn.com/explorations/life/china-begins-work-34-billion-dollar-resort-bahamas-697306.

[9] Anonymous interview at the U.S. Congress.

[10] U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Relations with Taiwan,” 25 February 2012, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35855.htm.