Brazilian Environmental Policy: Talk or Action?

After several years of deliberation amongst environmental organizations and agricultural lobbyists, on April 25 the Brazilian National Congress approved the new Forestry Code, sending it to President Dilma’s desk. Dilma has vetoed a number of the proposed law’s stipulations, including penalty-free infractions by landowners who avoid environmental registry.(1) Approved in 1965, the existing Forestry Code seeks to preserve the environment by specifying the exact amount of land that can be deforested by farmers. Unfortunately, the proposed reforms will harm the Amazonian region by allowing farmers and settlers to cultivate land without requiring the proper environmental safeguards.

In the Amazon, issues of deforestation, agriculture, ranching, and energy collide with protection of the environment, and the Brazilian government has historically catered to demands of the agribusiness sector. Professor Ans Kolk from the Amsterdam Business School says that, in the 1970s when environmental debates were emerging, Brazil implemented a national policy to exploit natural resources, under the official government slogan “integrar para não entregar” (integrate, don’t abdicate).(2) This development model, pursuing economic growth and industrialization, caused outrage among forest-protection groups in the 1980s.

An upsurge of public interest in the 1990s marked a new period of environmental policy in Brazil. Officials incorporated the rhetoric of sustainable development theories, changing the nation’s negative international image. More recently, the Amazon’s significant impact on climate change has drawn international attention. Political clashes have ensued, involving an array of interested parties, sparking national and global concern.(3) As environmental concerns continue to intensify, Brazil is predicted to play a more influential role in international negotiations, such as at the upcoming Rio+20 Conference.(4)

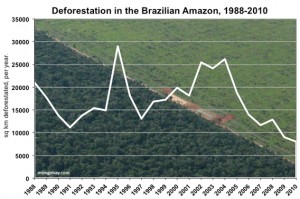

Although the Brazilian government has made an effort to implement green policy,(5) it has failed to find a balance between economic interests and environmentalism, ultimately choosing the former. This predominantly economic approach has worked to the detriment of the Amazon region, proving Brazil’s Congress impotent in preventing systematic deforestation and “land grabbing.”(6)

Article 225 of the Brazilian constitution upholds the universal right to enjoy an ecologically balanced environment, with local and national governments as its preservers. But it has become evident from continuous deforestation, coupled with the pardoning of environmental violations, that current laws and enforcement are insufficient in this capacity. Natural resources are left in the hands of private enterprises, ultimately leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

Influential actors competing for power and resources place a great deal of pressure on the government and slow negotiations on sustainable development policies. Consequently, the recent amendments will undoubtedly benefit the powerful agribusiness sector, rather than family-oriented, pro-environmental parties. While Brazil projects an international image of environmental consciousness and sustainable development, it still has a long way to go in making that image a reality.

The Brazilian government cannot continue to advocate conflicting positions. It must decide between protecting its fragile ecosystems and allowing corporate powerhouses to reap what they will.

To view citations, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.