Soiled Sovereignty: Land Issues in the Southern Cone

“People say you can’t go back. So, well what happens if you get to the cliff and you take one step forward? Do you do a 180-degree turn and take one step forward? Which way are you going? Which is progress?” –Douglas Tompkins, 180 Degrees South Documentary

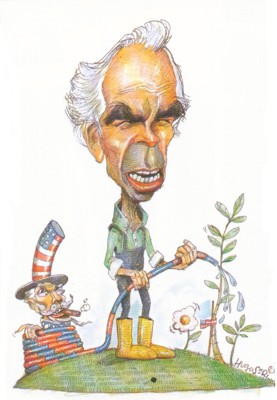

Latin America has had a tumultuous history plagued by the exploitation of natural resources and foreign political intervention. Western imperialistic practices have created a sense of resentment among native communities in the Southern Cone, which has been amplified through controversial cases, such as American Douglas Tompkins’s nature conservation campaign that began in 1991. Although Tompkins’s motives may be well intentioned, his territorial projects have proven to be politically and culturally problematic. This self-proclaimed philanthropist is the former CEO of the North Face and Espirit companies and, as such, spent a lifetime meticulously building his empire off the spoils of capitalism. He sold these U.S. businesses in 1990 for an estimated $150 million after deciding he no longer wanted to be a part of cyclical materialism, and subsequently used the funds to purchase land in Patagonia, Chile.[1] Today, he owns a total of 826,386 hectares of land in both Chile and Argentina.[2] The controversy surrounding his actions involves questions of national sovereignty and cultural integrity, which inspires further questions of legal regulations in Latin America to limit foreign purchases of real estate given painful colonial legacy.

From the beginning of Douglas Tompkins’s forays into buying land in Chile and Argentina until now, he has made his own 180-degree turn as a result of misguided assumptions. While he believed he was going south to serve as a savior of sorts, in reality, he was perpetually referring to his northern and U.S.-driven worldview in his assumptions about Chilean and Argentine land and people. The unintended ramifications of his original intentions to preserve nature severely infringed on the unique identities of the communities he set out to save.

Building an Eco-Empire

Tompkins and his wife moved to the southern region of Chile in order to establish their private estate on Pumalín Park. Tompkins’s interest in the region emerged from his rock climbing adventures in Chile as a young adult. When he moved to Chile in 1990, he established the Foundation for Deep Ecology, which advocates for true ecological sustainability by questioning conventional assumptions related to prevailing models of development. He then purchased Reñihué Farm in 1991, and one year later, established the Conservation Land Trust that is committed to preserve the wilderness in both Chile and Argentina. In 1997, Tompkins and his wife bought some property in Argentina, where they would eventually establish a residence in 2011, dividing their time between Chile in the summer and the Argentine Corrientes region in the winter.[3] For the Tompkins’, the late 1990s was a period when they concentrated on improving Pumalín Park, an area open to the public that has become the leading source of private sector jobs in the region, providing about 250 jobs throughout Chile. The park gained legal status in 2005 when it was officially recognized by the Chilean government. This allowed the U.S.-associated Conservation Land Trust to transfer its conservational holdings to Tompkins’s Chilean foundation.

Other land conservation projects in the region include Monte Leon National Park in Argentina and Corcovado National Park in Chile, which includes 85,000 hectares of land Tompkins bequeathed back to Chile in 2002. At that time, he stated, “it was a gift the president couldn’t refuse.”[4] Tompkins has met criticism by backpedaling from his original intent of land purchase (for his residence and national parks) with his proclamation to return land to the governments at a future date. Although this plan is admirable and he may be correct in his assessment of land mistreatment in the region, he is not in a position to impose his personal model for development.

Hypocritical Conservation

Doug Tompkins’s environmental initiatives in Chile and Argentina would have be more successful had his statements not been contaminated by hypocrisy and politically charged comments on Latin American development. Last year, the Tompkins’ began the process of selling their residence in Patagonia. Tompkins characterized the purchase as an “impulse buy,” even though they priced it to sell at eight million dollars.[5] The Tompkins’ excessive purchases at the time seemed somewhat contradictory, as he has since condemned the capitalistic system while continually reminding the public of his philanthropic role in Chile and Argentina. One example of his cultural cognitive dissonance is the particular concern of the indigenous community of the Mapuche Indians, who claim rights to the ancestral lands Tompkins currently owns. The Mapuche have rejected his offers to donate parts of the land back to them because expropriation efforts “cannot donate land that isn’t theirs.” To add insult to injury, Tomkins stated that he “felt lucky that he somehow escaped from the confines of the business class,” an ironic proclamation coming from a man who had already secured sizable wealth from mass production of “things people don’t need.”[6] In the same interview in which he made that statement, he concluded rather paradoxically, “I think it is not healthy for private individuals, foundations or companies to own a lot of land. I’d like to see land spread out in its ownership.” Not only is this statement at variance with his lifestyle, but it is also a utopian vision of a world without political boundaries, which environmental political theorists contend we are not remotely prepared to actualize.

Beyond these inconsistencies, Tompkins’s cultural stereotypes may be fundamentally flawed. In an interview he gave to Earth Journal he stated, “you come to realize that the passport is meaningless…I feel a strong bond with Chile and Argentina. I have even begun to think that I am caring for Argentina and Chile perhaps more than Argentines and Chileans. I feel like I’m sort of a de facto citizen because I am looking out for their national patrimony-the land-very carefully.”[7] This statement transforms philanthropy into delusion as he can no longer critically step outside of himself and his imposing perspectives. Along the way, there have been significant conspiracy theories and accusations regarding Tompkins’s intentions for the land. In 2006, Araceli Mendez, an Argentine congresswoman representing the Concepción region stated, “We believe this is a new way of trying to dominate the South American countries…it is dangerous for the defense of our national security to have the concentration of so much land in the hands of foreigners.”[8] Mendez, as well as a Catholic Church representative, went on to speculate about the “catch” of the American’s intention of eventually returning the land back to the government, citing possibilities of Tompkins seizing control of the Guaraní aquifer water supply. While many of these theories could be invalid, Mendez’s statements indicate that Tompkins is facing growing opposition from increasingly skeptical residents of the South American communities.

“Development of Underdevelopment”

In a March 2012 interview, Mr. Tompkins stated that he views Chile as an underdeveloped country because the government exploits the country’s natural resources to advance its economy, according to global trends of modernization[9]. While this process has never been environmentally sound, Latin America deserves to grow as it has been plagued by dependency cycles since colonization. Andre Gunder Frank, the late COHA Senior Research Fellow and master development analyst, has argued that in the case of Chile, the mercantile and capitalist system during the Conquest took hold of the country so quickly that it became defined by the external European powers more than its own intrinsic cultural substance during its development process. In some ways, “this development of underdevelopment has continued, both in Chile’s still increasing satellization by the world metropolis and through the ever more acute polarization of Chile’s domestic economy.”[10] This capitalist process cycles in the same way within historical contexts and stages. As a result, many countries in Latin America were preemptively stunted by colonial imperialism and one could argue that countries like Chile deserve to continue on the same path of modernization that other countries in the world have had the opportunity to take.

While it is commendable that individuals like Doug Tompkins want to see the land preserved and for communities to embrace “green” global trends, condescendingly buying land and then parceling it back to its rightful owners violates the national sovereignty of the country in the initial act of purchase. The former Senator to Chile’s Aysen region, where Tompkins purchased the majority of his land holdings in the country, stated in 2007, “if I were to go to the United States and buy a big area of Florida as an environmental preserve and tell people they can’t go here or there, I think the U.S. would kick me right out of there.”[11] Senator Antonio Horvath distinguishes the important double standard at play in highlighting the normalized response to territorial intervention in a country like the United States. If such a response is expected elsewhere in the world, the same respect must be given to countries like Chile and Argentina.

Conclusion

The tendency to abhor foreign intervention within a sovereign territory has been a particularly volatile issue throughout history. Tompkins neglects to consider this sad historical trajectory in a context of America’s fortunate political opportunity. Latin America has not had the same luxury of development as the United States; therefore, it must prioritize political and economic agendas differently. Furthermore, it is paramount to recall that the origins of countries like Chile and Argentina were misguided from the early periods of the Conquest, given that their natural resources were immediately exploited without formal consent for the colonizers’ benefit. In December 2011, Argentina legally limited the amount of land foreigners can purchase, which will deter controversy of this magnitude for their boundaries in the future. Without legislation like this, Argentineans and Chileans will be consistently deterred from orchestrating their own development, and they will find themselves operating in a dependency cycle that they may no longer be able to recognize, in sovereignty as well as in spirit.

This article is a sister to COHA’s print publication: The Washington Report on the Hemisphere. To subscribe click here.

[1] Larry Rohter “An American in Chile Finds Conservation a Hard Slog,” New York Times, August 7, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/07/international/americas/07patagonia.html?pagewanted=all&_moc.semityn.www.

[2] Poc a Poc Movement, http://www.pocapoc.org/imatgesgt/dough/BIODOUGTOMPKINS.pdf.

[3] Good Planet Information, “An Encounter with Douglas Tompkins, Philanthropist and Ecologist”, January 19, 2011, http://www.goodplanet.info/eng/Contenu/Focus/An-encounter-with-Douglas-Tompkins-philanthropist-and-ecologist.

[4] Good Planet Information, “An Encounter with Douglas Tompkins, Philanthropist and Ecologist”, January 19, 2011, http://www.goodplanet.info/eng/Contenu/Focus/An-encounter-with-Douglas-Tompkins-philanthropist-and-ecologist

[5] Juliet Chung, “Vast Open Space, Near the End of the World,” The Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303745304576357413621875804.html

[6] Jimmy Langman, “Conversation with Doug Tompkins,” Earth Island Journal, March 7, 2012, http://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/eij/article/doug_tompkins. Hereafter cited as interview with Jimmy Langman.

[7] Interview with Jimmy Langman.

[8] Monte Reel, “Argentine Land Fight Divides Environmentalists, Rights Activists,” Washington Post Foreign Service, September 24, 2006, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/23/AR2006092301054_2.html

[9] Interview with Jimmy Langman.

[10] Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America (London: Penguin Books, 1971).

[11] Lucy Knight, “Profile: Doug Tompkins,” New Statesman, January 25, 2007, http://www.newstatesman.com/environment/2007/01/douglas-tompkins-chile-land.

See Also:

Polar Ideologies Surface Due to Tempered Growth in South America