Replacing the Queen: Does a Name Change Make Sense for a Cash-Strapped Jamaica?

In 1961, when Jamaica seceded from the West Indian Federation, many believed what turned out to be the short-lived conglomeration of British Caribbean territories was a regime that represented a promising future for the county. The Federation ultimately disbanded and the failure was largely attributed to Jamaica’s secession, which demonstrated the considerable regional power the country was able to wield. As the first sovereign Caribbean nation to arise out of the British Empire, Jamaica set a regional standard in calling for independence as well as the establishment of a constitutional monarchy that continued to recognize the British monarch as the head of state. With the exception of Dominica, all independent Caribbean states have established constitutional monarchies directly following their separations from the United Kingdom.[1] Until now, few island nations have contemplated establishing a republic. [2]

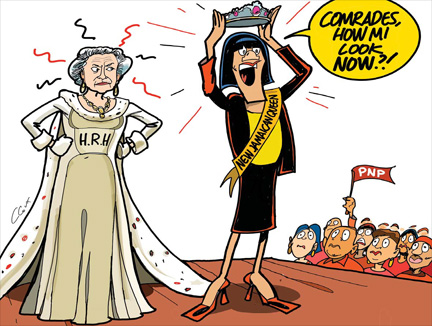

In January 2012, upon reassuming office as Jamaica’s prime minister, Portia Simpson-Miller promised her administration would begin the steps to undertake a transition to a republic. [3] Simpson-Miller previously assumed the prime minister role in 2006 upon the resignation of party colleague P.J. Patterson but was ousted by the Jamaican Labor Party’s Bruce Golding in 2007. She became the first popularly elected female prime minister of Jamaica in 2012, yet the liberal party’s pro-republican proposal appears to be a scheme to gain the political support of a crucial range of Jamaicans, rather than act as a successful forum based on a genuine government initiative, especially when one considers the contentious atmosphere in the country that came after Simpson-Miller’s election.

‘Time Come’: The Case for a Republic

In 2010, the Christopher “Dudus” Coke extradition scandal led to Jamaica’s return to international headlines. This incident led to Prime Minister Bruce Golding’s isolation and his decision to resign from office in October 2011. The remainder of the year witnessed various degrees of uproar. The JLP party elected a new leader, Andrew Holness, who took control of the party. Subsequent national elections resulted in an installation of the opposition, the left-leaning People’s National Party (PNP) with Portia Simpson-Miller at the helm. The new Prime Minister Simpson-Miller’s inaugural address in January 2012 discussed the importance of the new government being properly informed about the issues in the economy in order to take appropriate actions to revive it. In her address to the nation, she mentioned the desire to improve social conditions, reduce the national debt, and raise the island’s standard of living.

In addition to these upbeat talking points, Simpson-Miller also explained her proposal to end all of Jamaica’s colonial ties, which would include recognizing the CARICOM-sponsored Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) to function as Jamaica’s highest court, instead of the U.K.’s Privy Council. Minutes after her reference to the CCJ as a means to, “fully repatriate [Jamaican] sovereignty,” Simpson-Miller allowed her tongue to slide into patois, the colloquial dialect of Jamaica, with the phrase “time come,” meaning that the time had come for Jamaica to complete its separation from Britain. Simpson-Miller argued that a Jamaican republic would fulfill nationalistic pride, and that “completion of the circle of independence” would be achieved by “establishing an indigenous President as head of state.” She presented the Jamaican republic as a birthright, and a step that should accompany the fiftieth anniversary of Jamaica. Unfortunately, PNP sentiments have not been transferred to the Jamaican public. In a 2011 poll referenced by academic Jamaican Annie Paul in the UK Guardian, 60 percent of Jamaicans said they felt the country would be better off under British rule and 83 percent said Jamaica would be more prosperous had it continued as a colony. [4]

Intra-PNP Republic Dialogue

As expected, Simpson-Miller’s party stands behind her. Her predecessor, former Prime Minister P.J. Patterson, instilled the values of a republic in the PNP. In a speech to diaspora Jamaicans in the United Kingdom in June 2012, the High Commissioner to the UK ensured her constituency that there would be no repercussions as a result of the change. Furthermore, she communicated her view that having a local Head of State that would be truly representative of the Jamaican people is the only way to “complete the circle of true independence.”[5]

Comparing Financial Independence in the Caribbean Republics

For all of the positive rhetoric, changing from a constitutional monarchy to a republic is not merely ceremonial, it more significantly entails what some claim to is an exhaustive financial burden as well. In addition to jeopardizing substantial British aid, the removal of English ties would involve considerable costs, including the changing of royal insignia located on government buildings, rebranding the Jamaica Defence Force, Jamaican Constabulary Force, and Jamaica Combined Cadet Force uniforms in order to remove the royal textile presence.[6] Merrick Needham, logistics and protocol expert (and dual citizen of Jamaica and the United Kingdom), notes that nearly 20,000 personnel uniforms would need to be changed and that alone could cost nearly 217 million JD ($2.4 million USD). [7] He considers these costs to be unavoidable and thus necessary to factor in for the proper establishment of the new government as true costs of transition. Some of these expenses could easily be useful in other programs, but that has not halted other Caribbean islands from following the republican route.

In light of the financial burden brought on by the transition to independence, the Caribbean republics established a variety of different experiences in following the formula to republicanism post-independence. The Republic of Trinidad & Tobago experienced an effective constitutional transition in 1976 mainly due to its lucrative petroleum-based economy. The quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 led to a 9.6 percent annual increase in Trinidad’s GDP between 1974 and 1979, with a 21 percent increase in the 1970s, and the establishment of an almost unbreakable cycle of financial stability.[8] Although Trinidad remains a recipient of some designated funds from some international institutions, including the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, the nation is no longer eligible to receive funding from the largest aid donors of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, due to an ongoing and substantial increase in per capita GDP.[9] These increases in GDP represent Trinidad’s ability to stand on its own in the global environment.

If Trinidad & Tobago represents a successful transition to a republic, Guyana has embodied the opposite. In 1970, Guyana, one of the least developed countries in the Western Hemisphere, achieved independence with full sovereignty. The government’s nationalization of private businesses, instead of the development of private enterprise in the subsequent years, has helped produce a substantial external debt. A particularly solvent fiscal environment was never allowed to develop in Guyana. Over the years, the GDP has witnessed a series of slight rises, followed by sharp dips— both accompanied by stagnant or recessive population growth. Guyana repeatedly has had to struggle greatly in comparison to the booms routinely present in the Trinidadian economy, raising questions regarding the effectiveness of the republic.

Direct Economics of a Jamaican Republic

While a republican style of government may have been the appropriate choice for Trinidad & Tobago, it was hardly initially successful for Guyana. Based on this example, a republic installed in Jamaica may not prove a particularly effective governing vehicle because of the severe economic strictures, similar to the Guyanese case. Although Simpson-Miller was realistic about the state of the Jamaican economy, many in the media consider her aspirations for a republic arising on the island overly idealistic.[10] Jamaican debt is 140 percent of its GDP, which equals 60 percent of the national budget, and represents 89 percent of government revenue and grants.[11] Additionally, the United Kingdom is scheduled to contribute 75 million pounds ($121.6 million USD) to Caribbean development between 2011 and 2015, with Jamaica scheduled to receive a substantial fraction of this amount. Such support could be at risk if it becomes a republic.[12] While the British Queen is indifferent to the Jamaican republic, stating the issue of Jamaica’s head of state is up to the government and people of Jamaica, the statistical case against republicanism is formidable. [13] Without funding from Britain, Jamaica would have fewer funds for development and fewer avenues to adequately deal with its debts. In fact, the DFID has contributed over 66 million pounds ($107 million USD) directly to Jamaican debt relief and 1 million pounds ($1.6 million USD) to train Kingston in debt management.

Point of Contention: the Role of the Future President

The Prime Minister’s repeated mention of republicanism during her inaugural speech placed the issue at the top of her administration’s agenda, and also drew considerable domestic and international media attention to her agenda. However, the idea of a republic was not unique to Simpson-Miller. As it has been seen, former Prime Minister P.J. Patterson declared that Jamaica should aim to achieve republican status by the time he had left office in 2006. In 1995, the Constitutional Reform Commission ruled that the parliamentary monarchy would no longer have served the needs of Jamaicans.[14] In 2003, P.M. Golding announced that the fiftieth anniversary of independence would be “bittersweet” if Jamaica was not entirely independent from Britain. Neither prime minister, however, had the opportunity to achieve their goal of independence for Jamaica, since both left office under less than ideal circumstances.

When Patterson aspired to end the constitutional monarchy, the issue stalling the process was not so much the island’s excessive debt. Patterson suspended the borrowing relationship with the IMF in 1995 and proceeded to focus on the magnitude of the loan repayment.[15] He and fellow PNP members felt that the new president should be a chief executive with ultimate governing responsibilities. JLP representatives wanted absolute power to remain with the prime minister’s office, where an appointed president would have a ceremonial function and minimal governmental responsibilities similar to a monarch. The conflict between the two parties kept the proposed republican state languishing in parliamentary discussion; the question was never given over to the public for referendum. Patterson eventually relented on the duties of the presidency, as he made some strides to usher in a domestically born head of state even if it meant minor concessions on his part.[16] Unfortunately, the devaluation of the Jamaican dollar during Patterson’s term reintroduced a dire fiscal situation, which was then inherited by the next popularly elected Prime Minister, Bruce Golding of the JLP. Golding also considered the removal of allegiance to the Queen to be necessary, but never gave his full attention to tackling the issue. After the reinstitution of the IMF borrowing relationship in 2008 and the U.S. extradition battle over Coke, Golding was not in a position to marshal sufficient resources to decisively establish a republican state.

Andrew Holness’s JLP’s Republican Sentiments

The JLP has been silent as of late and has seldom directly addressed the issue of a transition to republicanism, given that its leaders see it to be a distraction to larger issues facing Jamaica. Leader of the opposition Andrew Holness has challenged the relevancy of both the dependence on the CCJ and amending the constitution to a republic.[17] In a July 2012 budget debate in parliament, Holness stated he would only pledge his support to the constitutional changes if it could be explained to him how the CCJ and [a Jamaican] Queen would help end poverty in Jamaica. His belief in rebuilding the government before restructuring it continues to ground his beliefs regarding the matter.

In a fiftieth anniversary tribute speech, Holness defined a means to obtain true independence. The multi-pronged definition listed both the fulfillment of human rights and raising the standard of living goals as the keys to full independence. He suggested actions characterizing maturity, such as “secur[ing] economic independence… provid[ing] each Jamaican the opportunity to access education, health, and other social amenities,” were more earnest methods of realizing “true independence” then bureaucratic methods.[18] Holness defined full sovereignty as a de facto state of being developed through cooperation between citizenry and government, not a de jure unilaterally implemented action with unknown ramifications.

For his part, in an address touting the official marketed title of all anniversary celebrations, Jamaica 50, Holness acknowledged that none of these actions were likely to happen overnight, but their attainment will make Jamaica a more ideal destination to live, work, raise families, and create businesses.

Conclusions

For the time being, present economic realities may not present the most opportune time for a change of government structure. With a stagnant economy, the best fiscal environment for the change may not be immediately visible to those in power. Such hesitancy could lead policymakers to feel the need to fashion a more appropriate time for building a republic, as opposed to waiting for the opportunity to organically develop. In a June 2012 letter to the editor published in The Gleaner, the centenarian news publication of the island, the guest contributor characterized the PNP as approaching the republic as a necessity for Jamaica, and not in need of citizen approval. If implemented, a new constitution would have to pass through both houses of parliament and reach a public referendum, but the PNP does not seem to be attempting to convince the public that a republic status is absolutely necessary at this time. It seems the PNP will do its work with the JLP in government and leave the public decision to chance.

Despite numerous concerns, protocol expert Merrick Needham is optimistic about a future republic and welcomes its arrival. P.M. Simpson-Miller had portrayed the CCJ and the advent of a republic as initiating essential, but for another time, in order to fully realize independence. She argues that as a small, underdeveloped country, the ability to symbolically stand alone as a nation would improve Jamaica’s status significantly. Due to various dependencies, Jamaica still makes many domestic policy decisions based upon international pressure. For example, the present government feels forced to continue the criminalization of cannabis for fear of American economic repercussions, despite the capital it could inject into the population. The Jamaican government resisted the extradition of Christopher “Dudus” Coke because it considered the U.S.’s case against him to be built on evidence in violation of Jamaican law, but the U.S. refused to submit further evidence. The country is also frequently subjected to foreign human rights campaigns targeting rampant homophobia in the culture. In October of last year British Prime Minister David Cameron threatened to remove HIV/AIDS funding if an arcane colonial law which criminalizing homosexuality was not repealed. The DFID followed through with this threat. [19]

If Jamaica were to finally emerge as an independent nation, assumedly, outside influence on the nation’s policies would decrease. Unfortunately, Jamaica’s economy is tethered to foreign aid and the advent of a republic will most likely not cause international opinion to drastically shift. If Jamaica wants to reach a position of indisputable sovereignty, it will require consistent economic and social development, a strengthened economy, reduction of debt and foreign reliance, as well as control of the country’s natural resources. Additionally, the government must generate greater support from the Jamaican people for obtaining the status of a republic.

Thus, independence should not just be a preference of parliament leaders alone, but of Jamaican citizens as well. If Kingston confronts the issues that cultivate Jamaican dependency, the country can eventually resolve the issue of full sovereignty. Despite its symbolic value, the economics of pursuing the establishment of the basis of a Jamaican republic it is likely to prove disastrous and distracting to the government, which could in turn cause a major setback in the country’s development. Realistically, Jamaica has more pertinent issues, which require the full administrative and fiscal attention of the government. For instance, both the economy and the island’s social situation requires at least the continuous flow of available funds from the government without a diversion of resources. Preferably, Jamaica should abandon hopes for a symbolic republic and assert its sovereignty through action before decree.

Aleia Walker, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

[1] In 1978 when Dominica achieved independence from the United Kingdom, the island became a republic with an indigenous president as head of state. In comparison, all other sovereign Caribbean states became constitutional monarchies upon independence with the British monarch as head of state.

“About Dominica,” The Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica, 2010, accessed September 17, 2012. http://www.dominica.gov.dm/cms/?q=node/8.

[2] Barbados has scheduled and multiple times postponed a referendum to decide the fate of the republic. In 2009 Saint Vincent and the Grenadines held a vote, which was defeated because they did not get the two-thirds approval necessary per the constitution.

“Constitutional Reform Referendum Defeated in St. Vincent & the Grenadines,” Antillean, November 26, 2009, accessed September 20, 2012, http://www.antillean.org/2009/11/26/constitutional-reform-referendum-defeated-in-st-vincent-the-grenadines/.

“Still a Voice,” Nation News, November 26, 2007, accessed September 2012, http://web.archive.org/web/20071128160635/http://www.nationnews.com/story/314949145377053.php.

[3] “Inaugural Address of Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller,” YouTube video, 28:29, posted by JamaicaGleaner, January 6, 2012, accessed September 16, 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx9D_t33_CY.

[4] Paul, Annie, “Jamaicans’ love of Britain May Yet See the Island Reject Full Independence”, The Guardian, March 9, 2011, accessed September 12, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/mar/09/jamaicans-love-britain-island-reject-independence.

[5] Siva, Vivienne, “High Commissioner Assures UK Jamaicans on Republic Status,” Jamaica Information Service, June 17, 2012, accessed October 18, 2012, http://www.jis.gov.jm/news/leads/30943.

[6] ibid

[7] “Republic? No Problem, Says Queen,” Jamaica Observer, January 8, 2012, accessed September 14, 2012, http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/Republic–No-problem–says-Queen_10521318.

[8] “Trinidad and Tobago: A Pattern of Development,” Islands of the Commonwealth Caribbean: a Regional Study. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1989, from Library of Congress, Country Studies, accessed September 24, 2012, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cxtoc.html.

[9] As of January 1, 2012, Trinidad & Tobago was officially removed from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development DAC lists which labels countries ad underdeveloped and allows them to receive money from the largest aid providers.

“Tewarie: Don’t Get Carried Away Over ‘Developed’ Status,” Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, November 2, 2011, accessed September 17, 2012, http://www.newsday.co.tt/business/0,149910.html.

[10] “Jamaica Debates Republic Option,” BBC News, March 5, 2012, accessed September 17, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-17251369.

[11] “The PM Must Change The Narrative”, The Gleaner, September 16, 2012, accessed September 17, 2012, http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20120916/cleisure/cleisure1.html.

[12] “Where we Work: Jamaica,” Department for International Development, 2012, accessed September 17, 2012, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Where-we-work/Caribbean/Jamaica/.

[13] “Republic? No Problem, Says Queen,” Jamaica Observer, January 8, 2012, accessed September 14, 2012, http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/Republic--No-problem--says-Queen_10521318.

[14] “Give Us the Queen,” The Gleaner, June 28, 2011, accessed September 12, 2012, http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20110628/lead/lead1.html.

[15] “No option – Jamaica Returning to IMF – Shaw – No Immediate Effect on Public Sector,” The Gleaner, July 22, 2009, accessed September 17, 2012, http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20090722/lead/lead1.html.

[16] “Jamaica Eyes Republican Future,” BBC NEWS, September 22, 2003, accessed September 16, 2012, http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/americas/3127742.stm.

[17] Luton, Daraine, “Closer To Quitting Queen- Gov’t”, The Gleaner, July 27, 2012, accessed October 18, 2012, http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20120727/lead/lead6.html.

[18] “Opposition Leader Andrew Holness’ Message for Jamaica 50,” Caribbean Journal, August 6, 2012, accessed August 6, 2012, http://www.caribjournal.com/2012/08/06/opposition-leader-andrew-holness-message-for-jamaica-50.

[19] “Why the British PM can Wield a Big ‘Homosexuality’ Stick,” Jamaica Observer, December 4, 2011, accessed September 15, 2012, http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/editorial/Why-the-British-PM-can-wield-a-big–homosexuality–stick_10047555.

See Also:

Let The Beat Drop: Dancehall Censorship In Jamaica

Coming Together To Strike Out On Their Own? Challenges, Change and Colonial Legacy in the Caribbean