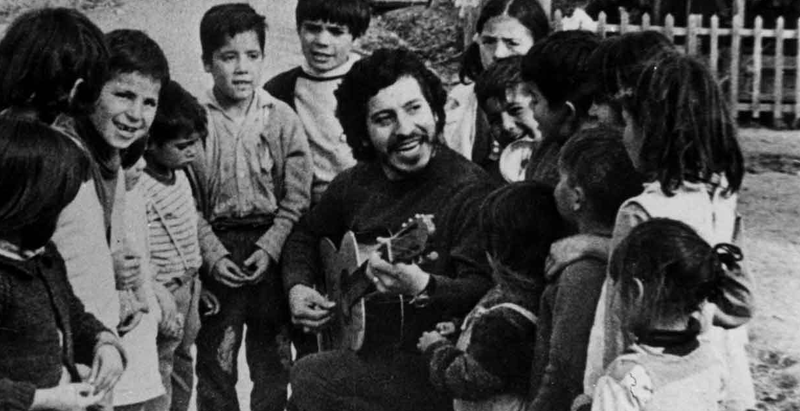

Víctor Jara, a Sacrifice of Love

- This past September 15th marked the 46th commemoration of the assassination of the distinguished singer-songwriter on the eve of the US-backed 1973 coup in Chile.

- The Military officer who shot the artist, Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez, lives in Florida and the US justice system has not approved his extradition.

By Patricio Zamorano

From Washington DC

The treacherous murder of Víctor Jara, singer-songwriter, a central figure of the revolutionary aspirations of the seventies, is closely linked to the victims of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, and by extension, of the entire planet. The singer-songwriter evokes the memory of the lives, and deaths of thousands of Chileans, but also of thousands of victims throughout the world who succumbed to the insensitive and irrational debacle of the cold war. The ideological hysteria of nefarious characters such as Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger (the latter of whom I had the pleasure of confronting some years ago here in Washington DC), extended its reach thousands of kilometers to pull the triggers that shot more than 40 bullets, ending the physical voice of a wonderful and distinguished popular singer.

This month marks 46 years since an assassination that is traumatic for both victimizers and the victims. It is a symbol of the mad ideological (in addition to moral) attempt to silence the social movements of a people, similar to the infamous assassination in Spain, decades before, of Federico García Lorca, another martyr murdered at the hands of world fascism. To murder an artist so beloved by the people is like trying to kill the dreams of a child: a heartless act in which something also dies in the victimizer the moment the gun is fired.

This commemoration of the assassination of Víctor (as he is called in Chile, just as Silvio, Mercedes, and Violeta are referred to, with their first names being sufficient for such intimate and universal friends) finds a Chilean society with justice still pending. The eternal specter of the word “impunity” intensely impacts the national soul. Decades have past, but the procedures of Judge Miguel Vázquez have succeeded, more than 40 years after the assassination, to convict soldiers Hugo Sánchez, Raúl Jofré, Edwin Dimter, Nelson Haase, Ernesto Bethke, Juan Jara, Hernán Chacón and Patricio Vásquez to 15-year sentences, which include convictions for the assassination, in those same fateful hours, of the ex-director of prisons, Littré Quiroga. Fifteen years in prison is obviously an eminently symbolic gesture; dozens more were murdered in what was formerly called the Chile Stadium, now re-baptized “Víctor Jara Stadium.” No sentence is long enough, even thousands of years, that would answer for what happened in this sports arena in September 1973. Justice is still asleep for all those anonymous victims. In this sense, the case of the murder of Víctor Jara serves as a beacon of light to at least open a faint glimmer of moral condemnation of those military personnel and the blatant dictatorship.

The list of soldiers is misleading; many of those sentenced were low ranking conscripts, around 18 years old, also victims in their youth, obligated by their superiors to shoot their compatriots, to shoot Víctor Jara himself, already wounded, laying before them, with his hands destroyed, smashed by rifle butts. A key point of the story of this enormous crime is that the material and intellectual author, the official who, playing Russian Roulette with his revolver fired the first shot at the head of Víctor, Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez, lives here in the US, in Florida, where many former oppressors of Latin America hide or show themselves in the light of day, fugitives from justice. Barrientos resists an order for extradition which for years now has not been enforced by the US justice system.

Many times, as a student in primary and secondary school, I visited the Chile Stadium for school sporting events in the Estación Central district. I distinctly recall its dismal structure, which gave me chills even before I knew this was the place where Víctor was assassinated and hundreds of other persons were tortured and killed. It is a roofed, vertical stadium, almost without natural light, submerged in a deep crevice carved out of the face of the earth. The bleachers rise in succession, stacked one on top of the other, creating four huge grim walls. The lower floors are below street level. Its passage ways are dark. Imagining the passion and death of Víctor is not difficult. Even now, what these victims lived through is palpable.

Víctor always had an important role in the reality of my childhood, adolescence, musical and university student life in Chile, as he did for so many in the country. Víctor’s own infancy and youth were very familiar to all of us who grew up in the Los Nogales and Villa Francia neighborhoods, in the popular commune of Estación Central, an area where he lived his own youth. Poor areas, of ochre colored ground, of hot Summers and wet and cold Winters full of mud, crossed by a canal of putrid water, the Zanjón de la Aguada (literally, Gully of Water); the zone portrayed by another great personality in the area, the world renowned writer Pedro Lemebel.

Víctor also worked as director of theatrical arts at what is now the University of Santiago, where I earned my journalism degree. Each year of university during the five years of my program, I imagined Víctor with his guitar over his shoulder, walking through the centenarian hallways of the former State Technical University (Universidad Técnica del Estado, or UTE as widely known), an academic center that still retains its social connection to its working class origins. But the most intimate experience of proximity was when I was part of the musical group Cuncumén. Víctor Jara began his musical career as part of the group formed under the inspiration of my first folklore teacher, the also legendary Margot Loyola. Víctor then, for me, emerged in all his human dimension during those final years of the dictatorship and transition to democracy.

During breaks from long music rehearsals, I held in my hands personal photos of Víctor with annotations of his handwriting. During such interludes, members of Cuncumén shared anecdotes about their artistic life with Víctor, his discipline, humanity, and sense of humor. For example, the members of Cuncumén told me that Víctor was very rigorous in his artistic practice. While he was artistic director of Cuncumén, when he had already grown as a singer, he demanded seriousness. He believed in an aesthetic school of work and responsibility when performing on the stage. He did not accept slacking. To arrive late to practice meant staying out for the first half hour.

Victor was one of the first directors who organized singers on stage in a way they could express their message not only through music, but also through clothing, facial gestures, and the ordering of space in front of the audience. That is the sort of work he developed, for example, when he directed the legendary band Quilapayún. Quilapayún provoked a powerful effect with its messages and music combined with ponchos and scenic display. In that sense, he harmoniously mixed his passion for theatre, his real love in aesthetic terms, with his massive and historic activity as a singer-songwriter.

I once had in my hands one of Víctor’s guitars. Margot Loyola placed it on my thighs during one of the rehearsals in her house near the National Stadium in Santiago. She kept it as a treasure. The emotion of having the weight of that instrument, which the great singer from Lonquén had in his hands, cannot be described in words.

After Víctor’s birth near the city of Chillán,500 kilometers from Santiago, the same area that gave life to another universal giant, Violeta Parra, in an impressive sidereal coincidence, his family moved close to the great capital, a rural area called Lonquén, about 40 kilometers south of Santiago. The singer portrays the beloved pueblo of his infancy in the song “El Lazo”. At 13 or 14 years old, I read about the small town of Víctor’s childhood in a magazine, a place reachable by bicycle. The bike we had in the family, ramshackle and with doubtful brakes, was the vehicle upon which I set out on an adventure. After about a four-hour journey, I arrived at houses still preserved in unreal rural style. There I searched and found many signs of Víctor’s songs of rural rhythms, ones less known and among my favorites. Those eight hours of pilgrimage left a great mark on me and closed the circle when years later, thanks to the turns of life, I became a student of Margot Loyola and a member of Cuncumén after the group’s return from exile.

One does not have to be a singer to feel Víctor near. His songs and his voice are almost like listening to a prayer woven in guitar chords, a song that invites sensitive souls to pause along the road. To close their eyes. To listen. Be transported to a communion of peace and love for humanity. To be shaken by the injustices of this world. To believe in humanistic values and the role of each one of us in a history we all share.

The religious allegory is no coincidence; his songs are filled with scriptural and spiritual symbols. Víctor began studies to become a priest but never finished. He wanted, instead, to serve the deity manifested in the sacrificial hands of an anonymous people. This is why his song rings so true, so real; it is because in his origin, Víctor is part of the people. He belongs to that lineage, the same as Violeta, of those who, with no formal musical training, and without knowing how to read scores, nor ever having known the rules of harmony or the construction of chord progressions, were creating songs from the very roots of the people, and of the earth, of a humanity mysteriously connected with nature, and based on a common history and primordial sentiments that make us brothers and sisters, without regard to language or cultural origin. This explains the impact of Víctor’s songs.

When one interprets, for example, “Te recuerdo Amanda,” the Japanese, Hispanic, or US public slowly enter a process of profound communion, almost sacred. The same happens with “Luchín,” or “Plegaria a un labrador,” or “Manifiesto.” They are songs that break through the routine character of earthly life and connect with a reality that we somehow recognize deep inside our very selves, though we had not noticed its existence before. It is because Víctor, on account of the period in which he was born in the early 1930s, still had a connection with the humanity that emerged during the critical era of social exclusion of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This era gave rise to the creation of social movements that, by the time of Víctor’s adolescence, were just beginning to be able to challenge the hegemony of the social sector which, as Salvador Allende said, “monopolized profits and privileges.”

It is the era of the women’s vote, the expansion of public education, the slow process of improving the lives of millions of families formerly excluded from public health. People in the heat of struggle for urbanization processes in areas built informally by those who migrated from the countryside to the capital. The revolution of 1968 encountered a Víctor already committed to the social and political process that was growing and consolidating around the Unidad Popular coalition of Salvador Allende. Víctor Jara surely felt profoundly that the world was a place of inequity, unjust for the majority, full of marginality, ready for social revolution and liberatory ideas. His artistic impetus could not be curtailed, and he succeeded in leaving behind chronic poverty, social marginalization, an alcoholic and absent father. He responded to his inner voice, one he found in music and theatre as a therapeutic form of expression that he carried in the heart. That, united with a process of profound social revolution led by Allende, brought together, like those surprises history gives us, a massive display of mutual recognition between the people and Víctor, making them one. Political process and song in the same battle for a more just society.

The legacy of Víctor is not only present in history books and in the recordings of his music. It is still alive, in his daughter Amanda, in his widow, Joan Jara, and in Manuela, daughter from her first marriage to the dancer Patricio Bunster. To say “the widow of Víctor” does not make sense. Joan herself has trained generations of Chilean dancers as well as those of other nationalities. When I met her in person in Santiago, I understood what the word commitment meant, and I lived Víctor in flesh and blood. Joan is no passive victim. She is a strong woman of unbreakable character, who continues struggling for justice for her husband and for the hundreds of thousands of victims of the dictatorship. For all these decades she has directed the Víctor Jara Foundation, which maintains the influence of the legacy of the singer-songwriter for future generations. Thanks to her, officer Barrientos was sentenced in a civil trial in Florida to pay millions of dollars in compensation for the assassination of Víctor Jara. And Joan will not rest until Barrientos is extradited and faces justice for his barbarity. I had the enormous privilege to interview Joan for Pacifica Radio in California in 2005 (click here), an interview in which one can still hear the emotion in her voice when speaking about her compañero.

That possible extradition would bring a partial close to the cycle of justice and end the impunity. The Chilean ex-military official joins a list of many oppressors who still get protection on US soil, among them Luis Posada Carriles, another confessed terrorist who lived a tranquil retirement in Florida and died last year without facing justice. And also Michael Townley, the sinister double agent who collaborated in various terrorist attacks and assassinations organized by the Pinochet dictatorship, who lives tranquilly in a witness protection program in some corner of the US.

But above all of this, the beautiful voice of Víctor Jara will continue to accompany us, no doubt, forever. The Pinochet dictatorship did nothing more than elevate even more the life and work of the beloved Víctor Jara. As Víctor said in a premonitory way in his hymn “Manifiesto,” released posthumously, he understood singing as something so profoundly rooted in the destiny of the community of people that surrounded him, that it even implied giving one’s life if necessary. This is why he says “song has meaning / when it beats in the veins / of the one who will die singing / the true truths.”

For this reason, far from hiding, fleeing into clandestinity or using his political privilege or international fame, he instead went out that morning of September 11, 1973 to his place of work, the UTE, to face with his university community what would come. Víctor would have never fled the common destiny; he suffered humiliation, torture, and a horrible death with the rest of the Chilean people. That morning of September 11, Víctor was going to sing at the university during the event at which Salvador Allende was to announce a plebiscite to end the economic and political crisis that the socialist revolution had triggered in the confrontation with the Chilean and Nixonian oligarchy. In four days, Víctor would be riddled with bullets in the basement of the Chile Stadium. But the blood spilled rose from those catacombs, and pushed by the chords of his guitar and voice, broke through the horror, and once again transformed into relief for the sensitive souls of this world. He set the foundation with his sacrifice for the hope of an entire people, who never gave up struggling to restore democracy. An imperfect democracy, still nascent, incomplete, sometimes unjust, but retrieved from under the boots of the military. As Víctor himself said in “Manifiesto,” “a song that has been courageous, will always be a new song.” . . .

The moral, political and artistic legacy of Víctor Jara can be read and heard directly in that recording of “Manifiesto.” The album in which it was included was left unfinished after his murder and published after his death. The words are strikingly premonitory of the passion and death the singer would suffer, almost in the Christian sense. His sacrifice immediately cemented the internal and international struggle against a dictatorship that demonstrated, in this treacherous assassination, its true moral degeneracy. And here follows the legacy of Víctor Jara in his own worlds. A legacy of love and humanity over the horrors of the injustices of history.

I do not sing just for singing

or just because I have a good voice,

I sing because the guitar

has meaning and reason.

It has a heart of soil

and the wings of a little dove

It’s like holy water

that blesses glories and sorrows.

Here my song infused

as Violeta Parra said

working-class guitar

with the fragrance of Spring.

This is not a guitar of the wealthy

nothing similar

My singing is made of workers scaffolding

to reach the stars

Because singing makes sense

when it beats in the veins

of the one who will die singing

the true truths

Not the fleeting flattery

nor international fame

but a song about the land

that penetrates to the heart of the earth.

There, where all arrive

and where all start

A song that has been courageous,

will always be a new song.

(Lyrics translated by Patricio Zamorano)

————————————–

Patricio Zamorano is a singer-songwriter, journalist and academic in political science. He is a former student of Margot Loyola and former member of the groups Palomar and Cuncumén. He resides in Washington DC.

English Translation of the text by Frederick B. Mills with editorial assistance of Roger Harris.