Understanding Brazil’s Recurring Rocky Road for Leftist Presidents

By Mitch Rogers, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here

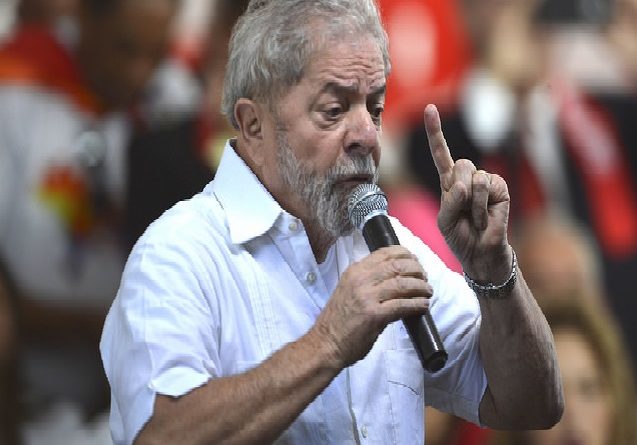

On January 18, 2017, twelve Democratic congresspersons from the U.S. House of Representatives signed a letter addressed to the Ambassador of Brazil to the United States, Sergio Silva do Amaral. The letter expressed “deep concern regarding the current state of democracy and human rights in Brazil,” continuing on to accuse the political factions behind last year’s impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff of protecting corrupt politicians, passing hugely unpopular policies, and attacking political opponents. [i] Specifically, the letter suggests that former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has been unjustly targeted by both media outlets and judge Sergio Moro due to his continuous political popularity and leadership of Brazil’s Workers’ Party (PT). On January 13, a similar letter was signed in the United Kingdom by various members of Parliament and distributed via the Guardian.[ii]

The letter refers to ongoing persecution against Lula, which began early last year. On March 4, 2016, Lula was detained and questioned by police on charges of corruption. Given there was no reason to believe that the former president would not have gone in for questioning peacefully, many interpreted the “unnecessarily spectacular,” highly-publicized, and forced deposition as a political attack to discredit Lula.[iii]

A week later, São Paulo prosecutors presented weak evidence for charges of money laundering in an attempt to produce a warrant to justify Lula’s “preventative arrest.”[iv] According to the prosecutors, Lula had not properly declared his ownership of a luxury penthouse at a beach resort in Guarajá, São Paulo. Lula maintained that neither he nor his family held any such ownership in the renovated properties. According to the investigators, if Lula was listed as an owner, it would have constituted a financial favor “in exchange for political benefit.”[v] The investigation has since been closed, and Lula and his family have been cleared of those charges.[vi]

Despite his forced deposition and allegations of political misdeeds, Lula persists as one of the most popular politicians in Brazil. He remains the figurehead for the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT), carrying them to the presidential palace in 2003 with his own election and keeping the party in power in 2010, when his protégé, Dilma Rousseff, was herself elected. In 2018, he will once again be eligible to run for president, which he has said he plans to do “if necessary.”[vii] PT party leader Rui Falcão offered an early endorsement of Lula, saying “[He] does not need to be nominated. He is our permanent candidate for president.”[viii] Lula is seen as the keystone to the PT, holding up and uniting the party, which faced massive challenges in 2016 after the impeachment of Rousseff, landslide losses in local elections in October, and its implication in the Petrobras scandal.[ix] Under Brazil’s Ficha Limpa or “Clean Sheet” law, if Lula is convicted, he will be unable to run for office for eight years, virtually destroying the PT’s chances of realizing any political gains in 2018.[x] (Current President Michel Temer is barred from running for reelection in 2018 due to this law.)[xi]

Justice Is Not Blind

Those who see the accusations against Lula as political sabotage invariably put the blame on one man: Sergio Moro. Moro, who for the past two years has been the judge spearheading the Operation Car Wash investigations, has topped several prominent magazines’ lists of most important people, including coming in at number 13 on Fortune’s “World’s Greatest Leaders” list.[xii] In spite of such accolades, however, Moro’s actions have often been less than admirable. He has consistently ventured too far into the political thicket to prosecute the PT while turning a blind eye towards the malfeasance of members of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). While Moro has no substantiated personal connections with the party, he has spoken at PSDB events, and his wife has worked closely with PSDB politicians.[xiii] He was the judge who authorized the raid on Lula’s offices and his forced detainment without establishing any formal charges.[xiv]

On March 16, 2016, Moro again exceeded his jurisdiction as a federal judge and illegally released to the public a private conversation between Lula and Rousseff, which further damaged Lula’s reputation.[xv] At a meeting held by the Landless Workers Movement (MST) on January 11, 2017, Lula addressed his various political antagonists, saying, “if Moro wants to become a candidate, that’s great… Everyone has that right. Join a party and go on the streets and ask for votes. What you cannot do is want to be a president by causing a coup with a stroke of a pen.”[xvi]

Last October, the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) accepted a petition filed by Lula’s defense team the previous July to investigate potential violations of Lula’s rights as a result of Moro’s conduct in office.[xvii] According to the petition, the aggressive persecution of Lula “violated Lula’s right to privacy, his right not to be detained arbitrarily and his presumption of innocence.”[xviii] Moro himself will be put under scrutiny by the UNHRC for his alleged illegal and inappropriate actions, possibly tainting the magazine-cover heroics and glamour surrounding him.

Brazil’s Persecuted Presidents as Precedents

Brazil appears to have a recurring problem with ousters of left-wing politicians and parties. Seemingly every twenty to thirty years during the twentieth-century, left-leaning presidents have been deposed whenever political elites felt their personal or business interests were being threatened. President Getúlio Vargas, nicknamed “the father of the poor,” was extremely popular among voters in the decades between the 1940s and 1950s, despite his initial position as an authoritarian dictator. His power, however, ebbed as much as it flowed: in 1945, Vargas stepped down from his post due to political pressures, and, after being popularly and freely elected president again in 1950, committed suicide in 1954 in order to avoid facing another ouster by his opposition.[xix]

In 1964, President João Goulart, commonly known as “Jango,” was deposed by a military coup d’état which installed a military dictatorship that lasted until 1985. Goulart, elected in 1961, instituted major progressive reforms throughout the country. By 1964, conservative civil factions as well as the military feared that Brazil was developing into a communist state, and executed a military coup to oust Goulart. Two decades of military-led dictatorship ensued, which censored speech and expression, violated human rights, and persecuted political dissidents.

Most recently, on August 31, 2016, President Dilma Rousseff was impeached after a 61 to 20 Senate vote. Rousseff had been temporarily removed from office the previous May; the impeachment in August made the removal permanent.[xx] Rousseff’s vice president, Michel Temer of the center-right Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, had been serving as interim president; upon Rousseff’s dismissal, Temer assumed the presidency and is slated to serve until the end of Rousseff’s elected term in 2018. As the New York Times noted, “unlike many of the politicians who led the charge to oust her, Ms. Rousseff, 68, remains a rare breed in Brazil: a prominent leader who has not been accused of illegally enriching herself.”[xxi] At most, her alleged misdeeds amounted to minor charges unworthy of impeachment, thus raising suspicions of political targeting and defamation.[xxii]

Lula is considered the first truly leftist president to be elected in the post-dictatorship era, and his future is beginning to mirror the fates of those progressive presidents before him. Seen in this context, the illegal removal of Rousseff and the political persecution of Lula seem to be an extension of what the congressional letter called Brazil’s “not-so-distant authoritarian past.”[xxiii]

Protecting the Future of the Brazilian Political Process

While Brazilians have long waited for a thorough investigation of Brazil’s historically endemic corruption, the political persecution that current investigations have unearthed is undeniably prejudicial. What began as a campaign to rout the illicit and unethical schemes out of Brazilian business and politics has gone astray, instead launching pointed attacks on a popular– if threatening– political party. While some PT-affiliated individuals may be guilty of wrongdoing, it is highly questionable that one party should be prosecuted almost to the point of political extinction, while many other parties receive relatively light scrutiny. In order for Brazil to truly be rid of its pernicious and lingering corruption, crimes must be investigated and prosecuted equally across the board, regardless of political affiliation or past status.

By Mitch Rogers, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Aline Piva, Brandon Capece, Kate Terán, Kayla Whitlock, Research Fellows and Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

Featured image: Agencia Brasil Fotografias. Taken from: Flickr

[i] Representative John Conyers. “Prominent Members of U.S. Congress Call on Brazil to Protect Rights of Political Opponents.” Press release, 18 January 2017. https://conyers.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/prominent-members-us-congress-call-brazil-protect-rights-political

[ii] “Standing in solidarity with Brazil’s Lula.” The Guardian, 13 January 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/13/standing-in-solidarity-with-brazils-lula

[iii] “United Nations to Analyze Investigation Against Lula.” plus55, 27 October 2016. http://plus55.com/brazil-politics/news/2016/10/united-nations-lula-investigation

[iv] Galvao, Arnaldo. “State Prosecutor Seeks Preventative Arrest of Lula.” Bloomberg, 10 March 2016. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-10/state-prosecutor-seeks-preventative-arrest-of-lula-papers-say

[v] “Brazil prosecutors request arrest of ex-President Lula.” BBC, 11 March 2016. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-35781257

[vi] “PF conclui relatório e indicia dona de triplex no Guarajá.” Folha de São Paulo, 18 August 2016. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2016/08/1804661-pf-conclui-relatorio-e-indicia-dona-de-triplex-no-guaruja.shtml

[vii] Moreira, João Almeida. “Lula já aquece motores para candidature em 2018.” Diário de Notícias, 23 January 2017. http://www.dn.pt/mundo/interior/lula-ja-aquece-motores-para-candidatura-em-2018-5621646.html

[viii] “Brazil’s Workers Party backs Lula for president despite corruption trial.” Reuters, 12 January 2017. http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-brazil-politics-lula-idUKKBN1512TN

[ix] D’Agostino, Rosanne. “PSDB e PSD crescem em número de prefeituras; PT encolhe.” Globo, 2 October 2016. http://g1.globo.com/politica/eleicoes/2016/blog/eleicao-2016-em-numeros/post/psdb-e-psd-crescem-em-n-de-prefeituras-pt-encolhe.html

[x] Reuters, “Brazil’s Workers Party backs Lula for president despite corruption trial.”

[xi] Canário, Pedro. “TRE de São Paulo confirma: Michel Temer está inelegível por oito anos.” Consultor Jurídico, 2 June 2016. http://www.conjur.com.br/2016-jun-02/temer-inelegivel-oito-anos-segundo-tre-sao-paulo

[xii] Fortune. 2016. “World’s Greatest Leaders.” Accessed 31 January 2017. http://fortune.com/worlds-greatest-leaders/sergio-moro-13/

[xiii] Cancella, Emanuel. “Sérgio Moro, um juiz a serviço da TV Globo e do PSDB.” Cart Maior, 18 June 2015. http://cartamaior.com.br/?/Editoria/Politica/Sergio-Moro-um-juiz-a-servico-da-TV-Globo-e-do-PSDB/4/33770

[xiv] Valle, Sabrina. “Tapes That Could Topple Rousseff Draw Fire on Brazil Judge.” Bloomberg, 18 March 2016. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-18/tapes-that-could-topple-rousseff-draw-fire-on-brazilian-judge

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Pitombo, João Pedro. “Lula defende eleição em 2017 e diz ‘nós voltaremos’ em ato do MST.” Folha de São Paulo, 11 January 2017. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2017/01/1848911-lula-defende-eleicao-em-2017-e-diz-nos-voltaremos-em-ato-do-mst.shtml (Translated by Mitch Rogers and Aline Piva)

[xvii] “UN Accepts Petition Stating Brazil Judge Violated Lula’s Rights.” Telesur, 26 October 2016. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/UN-Accepts-Petition-Stating-Brazil-Judge-Violated-Lulas-Rights-20161026-0020.html

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Poppino, Rollie E. “Getúlio Vargas.” Encyclopedia Brittanica, 5 May 2008. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Getulio-Vargas

[xx] Romero, Simon. “Dilma Rousseff Is Ousted as Brazil’s President in Impeachment Vote.” New York Times, 31 August 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/01/world/americas/brazil-dilma-rousseff-impeached-removed-president.html

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Representative John Conyers, “Prominent Members of U.S. Congress Call on Brazil to Protect Rights of Political Opponents.”