The ‘Wild Bunch’ Retains Its Firm Grasp on Banana Production

Central America, Ecuador, and Colombia supply the majority of the bananas to the United States. The region’s banana industry features an oligopic market dominated by three U.S.-owned multinational corporations, Chiquita (formerly United Fruit Company), Dole (formerly Standard Fruit Company), and Del Monte. From their massive plantations spread throughout Latin America, this “Wild Bunch” controls 65 percent of the world’s banana exports. The companies’ large size and ability to produce bananas very cheaply have allowed them to dominate the world market. Unfortunately, small-scale Latin American banana producers and plantation workers bear the cost of these low prices.

History: Bananas in Latin America

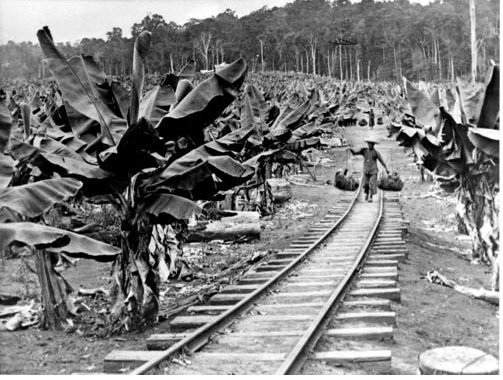

The Portuguese introduced bananas to the Western Hemisphere in the 1500s and began cultivating them in Brazil. Bananas existed in relative obscurity until the 1880s, when Jules Verne published a detailed description of the fruit in “Around the World in Eighty Days,” sparking an insatiable demand in North America and Europe. The Boston Fruit Company (later United Fruit Company), aided by its “Great White Fleet,” was the first corporation to export bananas cultivated in Latin America around the world, and held a complete monopoly of the market until the establishment of Standard Fruit Company in 1924. Both companies were notorious for vertical integration and often maintained production monopolies in their geographic zones of cultivation. In 1928, the United Fruit Company, in collusion with the Colombian army and under threat from the U.S. government, massacred a multitude of workers on strike regarding their dismal pay schedules and working conditions. During the Cold War, the United Fruit Company became more deeply entrenched in U.S. foreign policy, acting as a symbolic bulwark against the spread of socialism. Against this backdrop, which was further complicated by a dizzying array of personal financial incentives, American leaders were motivated to protect the commercial interests of United Fruit Company. Thus, United Fruit Company was implicated in the coup that overthrew Jacobo Árbenz, the democratically elected leftist president of Guatemala, in 1954, as well as the installment of repressive dictators throughout the region.

The Economics of Bananas

The Latin American banana industry is almost entirely export oriented. The United States, the world’s largest banana consumer, imports an average of 3.7 million tons annually.(1) Conversely, Central America exports approximately 85 percent of its bananas to industrialized countries. In 1955, bananas accounted for 41 percent of Costa Rican, 18 percent of Guatemalan, 50 percent of Honduran, and 74 percent of Panamanian exports. While bananas still comprise 39 percent of exports from Central America, and are the primary agricultural product of Honduras, Panama, and Costa Rica, only an estimated 11.5 percent of the global sticker price of bananas returns to the bananas’ nation of origin, while the remaining 88.5 percent accrues to the multinational corporations (MNCs), wholesalers, and retailers.(2)

Despite the tarnished record of many MNCs, many Central American countries have actively sought increased investment from MNCs. Indicative of this, Costa Rica exports 87 percent of its bananas under the Chiquita, Dole, or Del Monte labels.(3) These corporate giants require vast tracts of land for cultivation and thus rank among the largest landholders in Central America. Yet, while conducive to increased exports and foreign investment, the propagation of banana plantations throughout the region carries the often-nefarious consequence of overemphasizing banana cultivation, meaning that most Central American countries fail to grow enough food to meet domestic needs. Between 1960 and 1985, Honduras experienced a 31 percent decline in per capita production of basic grains and was forced to increase cereal grain imports by 90 percent, despite possessing adequate natural resources for grain production.(4) Consequently, these countries have become increasingly dependent on developed countries to supply both markets and necessities.

In recent years, bananas have become a source of contention in the global market. Starting in 1993, bananas grown in Asian, Pacific, and Caribbean countries enjoyed virtually duty-free access to the E.U. market while it imposed taxes on Latin American bananas. In September 1997, the World Trade Organization ruled, on a joint case filed by Ecuador, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and the United States, that the European Union had to phase out these tariffs because they were unfairly preferential.(5) In 1999, however, the European Union reinstituted a tariff-rate quota system on Latin American bananas, and in response, the United States and Ecuador placed sanctions on E.U. products. In 2006, the three parties reached an agreement allowing the European Union to maintain a €187 tariff, but no quota, on Latin American bananas. Because Latin America grows bananas on a much larger scale than Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, their production costs are significantly lower and their bananas are able to crowd out those produced in other regions

The Plight of the Banana Laborer

Under current constructs, the working conditions of the Latin American banana industry rival that of the much-maligned sugarcane industry. Conditions on Latin American banana plantations have long undermined workers’ health through long hours and daily contact with pesticides and fertilizers. Such workers comprise a substantial portion of the labor force of banana-producing countries; large banana plantations employ 5 to 10 percent of the Honduran and Costa Rican work forces and 380,000 directly employed workers in Ecuador.(6) In Costa Rica, each worker produces approximately $20,000 worth of bananas annually but often earns only $2,000 for his or her labor. Workers frequently labor between 10 and 12 hours, six to seven days a week, and while 30 percent of these plantation workers are permanent, the remainder are employed on 90-day contracts.(7) As a result, many laborers must move between plantations to maintain even a modest income. However, because so few companies control the market, working conditions vary minimally from plantation to plantation. As migrants, these workers never enjoy benefits such as vacation time or social security, and most are only able to eke out a meager existence; a typical company barracks, shared by four workers, is a 2.3 by 3.3 meter room.(8) Due to the miserable living conditions and sense of despair among laborers, substance abuse, violence, illness, sexual abuse, discrimination, and broken families are all too common on banana plantations.

Despite efforts to unionize banana plantation workers in Latin America, unions remain far from universal and are hindered by resistance from the three corporate giants. While it is not uncommon to find unionized banana production in Central America, Panama and Colombia, less than 1 percent of Ecuador’s banana workers belong to unions. Unionized banana workers in Latin America can earn up to $10 a day, while their non-unionized counterparts have to settle for between $3 and $5. Most unionized banana workers have access to health care, schools for their children, and housing, benefits virtually unattainable for non-unionized banana workers. In Ecuador, the world’s largest banana exporter, low wages and poor working conditions due to a dearth of unionization encourage decreased wages and worsened conditions in other banana-producing regions, as they strive to cut costs to compete with Ecuador. Despite efforts in 2001 to block unionization in Panama, Chiquita employs more unionized workers than the other three major banana corporations, such that a much higher percentage of Chiquita workers earn decent wages and receive benefits compared to competitors’ laborers.(9)

Impacts on the Environment

Aside from horrendous work conditions, banana cultivation by the major three companies has had detrimental impacts on the environment and public health. The spread of plantations has sped up deforestation in Latin America, and intensified cultivation techniques quickly deplete arable land. Chemicals used in fertilizers and pesticides have contaminated many water supplies surrounding banana plantations, and in some cases may have harmed the health of residents of nearby towns. In 2004, Costa Rican banana pickers sued Dole, Chiquita, and Del Monte for using the powerful fumigant DBCP for more than two decades after it was banned in the United States in 1979. The charges further allege that the MNCs knew that the chemical could cause devastating health defects in humans, such as damage to the reproductive system.(10) Finally, chemical run-off from the plantations has precluded many neighboring small-scale organic farms from successfully obtaining USDA organic certification.

Policy Recommendations

Breaking from the destructive practices of banana cultivation is possible. Latin American countries, particularly Ecuador, must play a more active role in implementing laws protecting workers’ rights, mandating minimum wages, and facilitating unionization among banana laborers. Countries should also consider following Panama’s lead by lending money to farmers to form farmers’ cooperatives, which sell to these multinationals instead of toiling under their direct control. Such cooperatives have greatly improved working conditions in Panama, increased the number of small-scale farms, and allowed farmers to earn a much larger share of the profits through the power to negotiate prices. These cooperatives also have the potential to reduce the power of the major corporations because they remove the MNCs’ role in cultivation, transportation, and vending. Co-responsibility between importing and cultivating countries, in more strictly regulating the chemicals used in banana production, would also serve to mitigate some of the environmental damage and public health concerns caused by the sustained use of fertilizers and pesticides. As trade becomes increasingly globalized, consumers of the world’s fruit—and beneficiaries of such consumption—must take responsibility for the plight of those whose labor produces it.

To view citations, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.