The Road to the FIFA World Cup

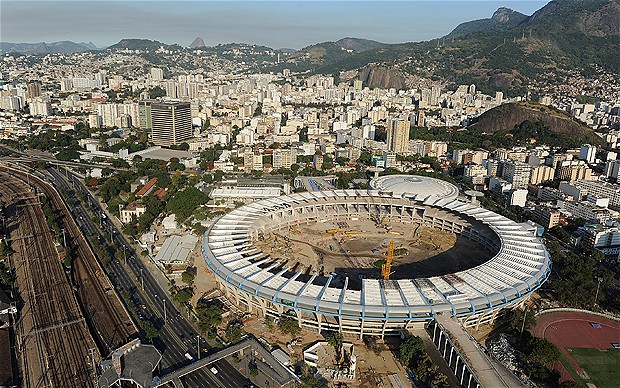

The road to the World Cup seems endless as Brazil continues to face problems carrying out its elaborate construction plans. With a strict deadline and a worldwide audience awaiting its commencement, Brazil has found itself in a state of crisis. While construction is under way at all stadiums hosting matches, arenas and other facilities in Sao Paulo, Natal and Manaus need to be ready in time for the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup, which is considered the World Cup trial run. Brazil was awarded the event by the Zurich-based International Federal Football Association four years ago, yet dozens of road and public transportation projects, which the government has predicted will be the biggest legacy of the tournament, are still on the drawing boards[1].

Events such as the World Cup and the Olympics are now being termed “mega-events” and the central idea behind them is to not only promote worldwide unity, but also to give the host country a unique opportunity to display their national assets while having a positive economic and social impact on the nation. Government officials in Brazil, along with the Local Organizing Committee of the World Cup, claim that the central focus throughout their preparations is the welfare and prosperity of the ordinary citizens in Brazil. However at this point, only anecdotal evidence regarding these claims exists[2]. Rather than spending immense measures trying to meet the world’s expectations, Brazil needs to take advantage of this opportunity to effectively expedite and expand the construction piece of its infrastructure.

Purported Benefits to Mega-Events

Brazil also needs to focus its attention on creating beneficial economic avenues that could successfully improve the lives of the Brazilian people. The assumption that colossal sporting events are good for host nations and their citizens rests on a number of conjectures[3]. According to an article in Political Insight, sports mega-events firstly can inspire the masses, including youth, to take up sport or some form of physical activity, thereby improving their health. Secondly, such events are economically lucrative, bringing revenue from increased tourism, among other sectors. Thirdly, mega-sporting events engender a ‘feel-good’ factor among citizens of the host nation, which consequently affects their wellbeing. Fourthly, these events provide a much needed urban regeneration to accelerate and improve society. Lastly, states benefit from showcasing themselves internationally – leading to an increase in so-called ‘soft power’, or their ability to pursue and persuade international relations through their cultural and economic influence[4]. Despite these five potential benefits, there is a complete lack of substantial proof that can back up these declared claims.

Brazil is now repeating many of the same mistakes that plagued the development of the World Cup in South Africa in 2010. Primarily, these mistakes center on the combination of financial planning, distribution of funds, and attempts to uphold local social and environmental stability and development. During the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, the attention of political leaders and municipal officers, along with national and local funds, were diverted from local matters towards efforts for the World Cup[5].

Leaving the Locals behind

The intensity of World Cup preparation and the pressure on host cities to deliver also causes many to allocate some of their most capable staff towards specialist teams that work on the lead up to the event as much as four years prior. While in some cases this could have led to a boost in capacity within municipal structures as they prepared themselves, it also tended to leave gaps in skills and focus in programs that have little to do with the World Cup[6]. This has become an issue in Brazil in the past two years. It is almost as if the global problem of brain drain is occurring on a local scale causing the ongoing development of the country to be at a stand still while all efforts are redirected towards the World Cup. Other attentions are also being deterred from overseeing the actions of government officials leading to the development of a severe lack of transparency regarding monetary funds for the events. Various attempts at avoiding corrupt practices in project management have been made throughout World Cup preparations in developing host nations. The inevitable corruption that occurs, along with abundant efforts to meet the strict infrastructure deadlines for the event cause the key question of if the World Cup organizers can proceed in developing Brazil for the World Cup without leaving the locals behind[7]. In other words, can the large corporate and political actors in charge of this event actually focus their efforts on the interests of the Brazilians rather than their own financial benefits?

Often, national economies of host countries can end up facing serious consequences associated with long-term costs. Scholarly consensus has stated that benefits linked to major events are greatly exaggerated by sponsors called upon to produce significant events. Firstly, the supposed “increase” in spending directly attributable to the games may end up being “gross” measure rather then a “net” measure[8].. The difference between these two methods of measurement is that the “gross” measurement solely focuses on all national profits throughout the event, however, fails to account for the displacement of regular spending by Brazilians, and other routine business travelers who are now avoiding the host cities. After the recent Olympic games in London, the BBC reported that the games deterred visitors from popular destinations and tourist revenue had diminished as a result. An employee at one of the UK’s largest department stores claimed that “Everyone who is either in Stratford, or are Londoners who usually shop here have gone away until the Olympics are over”[9].

Promises and Pitfalls

The ongoing question regarding the actual benefits of recent major sporting events can perhaps be answered by looking into the economic promises and pitfalls of the World Cup experience in South Africa. The economic promises fall under the notion that by hosting sporting events, politicians and local city planners fixate on promoting the idea that constructing a “world city” complete with first class amenities becomes a necessity and a means to compete for future foreign investment in a highly globalized world. However, in an attempt to prove that Africa was a “developed” enough nation to meet FIFA standards, allowances for the implementation of advanced infrastructure came at huge financial and social cost for the host country.[10] These costs mostly came about as a result of the rapid construction of stadiums and lack of concern for the local population, especially those that had been promised an increase in the positive social changes coming out of the tournament. Much of the allotted funds went to social development needs, including the “Adopt-a-School Program”, which would provide new housing for people now living in shantytowns, as well as the implementation of anti-drug campaigns were re-directed towards workers costs to ensure speedy production of buildings and roads. These expenses are now occurring in Brazil as the construction for the tournament pushes forward and workers’ strikes continue to cause problems. Delays to building projects for stadiums, airports and public transport are made worse by rapid inflation due to the hurried pace of development.[11] There are many critics in the country, such as the prominent Brazilian journalist Juca Kfouri, who has commented that the rapid implementation of infrastructure promotes a lack of consideration for long-term standard of living effects. Kfouri claims “There is too much emphasis on stadiums and too little focus on the legacy for the cities involved. I am against a World Cup that builds huge arenas where there is barely professional football”.[12] In Brazil, four arenas costing approximately £720m 1,152,553,226 USD are being built in cities that do not have strong soccer teams or leagues. It seems inevitable that these stadiums will become nothing more then giant “white elephants” sitting on land that could be put towards governmental housing for the 20 percent of the population that live in favelas. Favela dwellers are most affected by the production of these major events and many have been displaced in the chaos that accompanies the implementation of the World Cup, an inevitable byproduct of the social impacts that major events have produced.[13]

The developmental impacts of monumental sporting events in the periphery are repeatedly touted, although there is little guarantee that the actual effects contribute to poverty reduction specifically. In labeling mega-events a solution for poverty alleviation, as many scholars and observers have been inclined to do, careful considerations should be required in order not to inflate their ability to cure a country’s developmental challenges.[14]

Resolving Tensions

Another issue facing the successful execution of mega-events is the necessary cooperation of all parties involved. Rapidly developing countries, like Brazil, face the inevitable undermining of their abilities to thoroughly implement fast approaching events without the input of other organizations involved such as FIFA and the LOC. Currently, Brazil is falling directly into the developmental traps foreseen by the hosts of such events.[15] The occasion is supposed to be a worldwide celebration of unity as well as an opportunity for a country to showcase its capabilities and culture to the world. However, the affair has been marred by ongoing delays in construction due to workers going out on protracted work stops and the government’s failure to take prompt and required action. In May 2012, LatinNews published a report detailing the events of a six-hour meeting in Zurich to resolve some of the issues that had come up after tensions between FIFA and Brazil heightened. This turned out to be a crucial forum for Brazil to focus and seize upon the opportunity that it has been awarded by FIFA. That body’s president, Sepp Blatter, declared the organizations problems were “over” after the Zurich meeting and claimed that various Brazilian government officials will join FIFA’s World Cup organizing committee, allowing the Brazilian government and FIFA to work more closely together before the games.[16] With the prospect that the revitalizing of this alliance will combat many of the issues that have arisen, Brazil continues in carrying out their construction plans.

Creating a Sustainable World Cup

One way that Brazil can enhance the economic and self-esteem benefits of the World Cup is by taking into account the legacies of social and environmental impacts of large-scale events. When analyzing the legacy of the tournament, environmental impacts weigh in at the top. These environmental effects inevitably serve as a mirror for future social and political reformations and actions that take place.[17] Brazil, as a country with a long history of environmental degradation in the form of slash-and-burn deforestation among other harmful development practices, must work rigidly to promote a more effective method of expansion. The most important of initiatives is to mitigate the huge carbon footprint being left behind by such prodigious events such as the World Cup. Ernst and Young associates calculated that the estimated carbon footprint of the 2010 World Cup was 896,661 tons of carbon, with an additional 1,856,589 tons contributed by air transport. Various measures of development could have been utilized to ensure a more environmentally sound post-event Brazil. Some examples are: utilizing energy efficient technologies, alternative sources to meet irrigation needs, an integrated waste management system, and to seek out a universal energy as an efficient means of transportation.[18] If Brazil can implement these innovative ideas into the construction of their infrastructure, it will be not only be able to significantly enhance its reputation on the world development map, but also become internationally recognized as being certified to construct sustainable stadiums and living quarters. This would be one of the most vital benefits resulting from hosting a monumental tournament, as well as going a long way towards future improvements in guaranteeing the growth throughout Brazil.[19]

If all parties involved in the event can effectively work together and uphold their ends of the bargain, they could all be proud of the positive legacies resulting of the decisions made by FIFA authorities. While the pressure of successfully executing this event will be great, hopefully, the global audience will help to effectively cauterize the wound which is wide spread corruption and simultaneously encourage social development.[20]

If the allotted funds are appropriately used, as particularly delegated by the Local Organizing Committee (LOC) in charge of making certain that the preparation, management and operations of the event are effective, then a positive domino effect of direct proportions and values can be constructively employed. If this is done, then the outcome of the 2014 World Cup, as well as the impending Olympic games, will result in a broad beneficial step in social and economic development for Brazil.

Brielle Sharkey, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

[1] “World Cup 2014 delays expose Brazil’s planning and infrastructure weaknesses.” MercoPress, September 17, 2011.

[2] Brazil and fifa put aside their differences. (2012, May). Retrieved from http://www.latinnews.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=51632&period=2012&archive=788279&Itemid=6&cat_id=788279:brazil-and-fifa-put-aside-their-differences

[3] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[4] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[5] Cottle, Eddie. South Africa’s World Cup: A legacy for whom?, Scottsville: UKZN press

[6] Robbins, Glen. “Major International Events and the Working Poor: Selected Lessons for Social Actors Stemming from the 2010 Soccer World Cup in South Africa.” Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing, June 2012. Web. http://www.easybib.com/cite/form/website.

[7] “World Cup 2014 delays expose Brazil’s planning and infrastructure weaknesses.” MercoPress, September 17, 2011.

[8] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[9] Wallis, Gary Anderson & Holly. “Olympics: Are Games ‘a Disaster’ for London Businesses.” BBC News. BBC, 08 Mar. 2012. Web. Dec. 2012.

[10] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[11] “World Cup 2014 delays expose Brazil’s planning and infrastructure weaknesses.” MercoPress, September 17, 2011.

[12] Duarte, Fernando. “Brazil’s World Cup Planning Hits Problems on and off the Pitch.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 31 Mar. 2012. Web. 14 Dec. 2012.

[13] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[14] “World Cup 2014 delays expose Brazil’s planning and infrastructure weaknesses.” MercoPress, September 17, 2011.

[15] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[16] Johnathan, Grix. “The Politics of Sports Mega-events.” Political Insight, September 2012. http://www.politicalinsightmagazine.com/?p=894 (accessed September, 2012).

[17] Cottle, Eddie. South Africa’s World Cup: A legacy for whom?, Scottsville: UKZN press.

[18] Earnst and Young Terco. “Sustainable Brazil Social and Economic Impacts of the 2014 World Cup.” N.p., 2011. Web.

[19] Cottle, Eddie. South Africa’s World Cup: A legacy for whom?, Scottsville: UKZN press.

[20] Cottle, Eddie. South Africa’s World Cup: A legacy for whom?, Scottsville: UKZN press

See other COHA publications:

Fútbol Femenino: A Reflection on Women’s Rights in Argentina