The Race for the White House: A Call for a Regionally-based Enlightened Foreign Policy toward Latin America

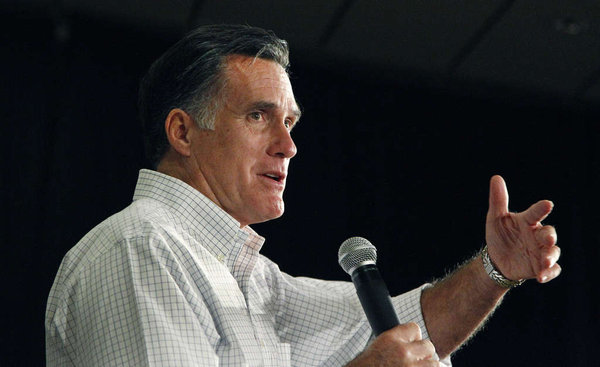

With a little under a year remaining until the next U.S. presidential election, a coherent and sustainable area policy toward Latin America remains absent from the campaign literature and both presidential parties’ electoral strategies. In fact, a true U.S.-Latin American foreign policy—one that involves succinct initiatives rather than populist rants or ideological outbursts—has yet to be developed in the 21st century. If one is left to assess the future of U.S.-Latin American foreign policy simply by relying on the last three years of the Obama administration, or the empty rhetoric from the entire Republican field, the future appears rather bleak. Nonetheless, one candidate, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, has detailed a slightly weightier, yet basically ill-informed vision that promotes regional integration and the strengthening of economic ties. His plan is almost entirely dominated by commercial interests and remains in large part focused on securitization. Barely moving beyond a fallow bilateral approach harnessed during the post-World War II years, Romney’s Latin American policy does manage to squeeze out some relatively non-bombastic verbiage.

For his part, President Obama has yet to outline a detailed vision on Latin American issues for his reelection, but the short blurb on the White House policy page indicates a usefully backseat nature that Latin America has held for the current administration. In a few words, U.S. foreign policy toward the region is described by the Democrats as being committed to “a new era of partnership with countries throughout the hemisphere, working on key shared challenges of economic growth and equality, energy and climate futures, and regional and citizen security.” The Obama administration can point to the recent passage of the free trade agreements, negotiated during the Bush administration, to complement this short, rhetorical ‘vision,’ but other than that, the administration’s foreign policy toward Latin America has been frail, if not exiguous.

In defense of President Obama, the Bush Doctrine ignored Latin America as well, but far-right figures in the region were relatively successful in attracting U.S. resources as well as favorable treatment by constructing their foreign policies beneath the umbrella of a specious war on terrorism. While Colombia (through Plan Colombia) and to a lesser degree Mexico (through the Merida Initiative) successively gained U.S. attention and resources, the newly achieved backing only sought to strengthen the overall security capacity of these anti-drug forces in return for supporting the U.S. global securitization policy. A definitive conclusion regarding the success of this policy has not yet been reached, but the need for a regional vision that would promote strong ties to the U.S. and create regional integration has always been in process.

Thus far, there has been only one plan worthy of a conceptualization being offered to the region that even considers such an approach to Latin American policymaking. Presidential candidate Mitt Romney, who is generally considered intermittently to be Republican frontrunner, and who is running close with President Obama in national polls, has recently laid out a 43-page document detailing his vision for U.S. foreign policy. In a formidable feat for Republican regional policymakers, he actually presents (if nothing more) to address a vision for Latin America, promoting regional integration, over the current bilateral approach directed primarily toward Washington’s allies in the War on Terrorism.

Romney, advised by a committee professedly oriented toward Latin America and headed by a series of pro forma old hands with tired notions, as well as some academics and respectable diplomats, details the creation of a regional institution called the Campaign for Economic Opportunity in Latin America (CEOLA), in order to promote “a vigorous public diplomacy and trade promotion effort in the region.” If this program’s goals remain the same, its specific details will remain vague and uninspiring; that said, the mere offer of such a new template contrasts sharply with the approaches currently being proposed by other candidates and the Obama administration, which has hardly done better in offering much and delivering little. In any case, Romney unsurprisingly presents a heavily business-tilted regional approach to integration that claims to promote a more democratic and economically responsive Latin America. His plan appears to follow the neo-liberal model based on institutionalism, which asserts that U.S. interests are better served through multilateralism and regionalism rather than through bilateralism.

If CEOLA seeks to achieve the creation of a new regional forum integrating South America with Central and North America, a bona fide U.S.-Latin American relationship could be developed in the process. The Romney formula provides a meager platform to discuss a wide array of issues from securitization to economic policy, as well as a methodology that could allow states to develop their own regional approaches for improving records on human rights, alleviating poverty, and other issues plaguing Latin America. The region, once consolidated and integrated, could also pursue a universal approach toward justice, utilizing transnational courts that adhere to cultural and legal traditions while also addressing the shortcomings of fledgling criminal justice systems that characterize the region. If it is unsuccessful however, such a system could add to the region’s woes brought on by endemic corruption.

Obviously, the ultimate success of Romney’s regional policy would rely on a variety of factors, including the level of activism on the part of the U.S. in the development of hemispheric initiatives. Washington must only be involved in the initial creation of big policy and have no greater power than carrying out a formal advisory role. CEOLA would symbolically represent a comprehensive, if not a bold approach for a new path forward in the 21st century, but not an interventionist one. At this point the Romney plan is sufficiently multifaceted to provide him with significant wiggle room, if this is what is really sought. This is not to argue that the post-9/11 policies of securitization are not in need of being replaced by a more developed, regional vision for Latin America. Only the development of a new institution would provide the possibility for new directions with specific goals that are widely accepted.

To his supporters, Romney is the only candidate that has offered a regional vision for Latin America, albeit one at risk of being more of pap and treacle than of sounder stuff. Ironically, it may be more suitable for regimes that are not likely to easily tolerate U.S. intervention of any sort, and have an increasing demand for Latin American sovereignty, to pick and choose their own policies. President Obama should embrace such a move in order to establish a more integrated, equal, and just Western hemisphere. Until a new plan that moves beyond securitization is realized, Latin America will remain in the backwaters of policymaking and under the canopy of an overreaching U.S. foreign policy.

In any case, the time for a renewed U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America is not only long overdue, but is also being demanded by the region here and now. Mitt Romney has at least presented a starting point for a 21st century foreign policy that will likely go nowhere. As wobbly as it is, the other candidates, including the president, could do far more, but will at least have a modest road to build upon with this model.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.