The Panamanian Political Roller-Coaster: A Look Backward and a Look Forward to the 2014 Elections

Source: www.cam111.com

President Ricardo Alberto Martinelli (2009-present) has proven to be a shrewd politician, frustrating opponents who had expected much less from him. Throughout his tenure Martinelli has shown that he knows how to play the political game. He has used force, especially against indigenous groups; he also coaxed support, expanding cash transfer programs for the poor and establishing pensions for the disabled and the elderly; and he has turned to mediation, deftly settling controversies within his own party. While Martinelli’s many critics can be loud in denouncing him, his overall popularity remains high.

Nobody doubts President Martinelli’s ambition and aggressiveness. He is scheduled to leave power in 2014, but he will probably only step aside if he succeeds in finding a suitable heir. His plans seem to involve positioning himself as the power behind the government, and even if his party loses, re-emerging, as a Panamanian version of Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, coming back from the near-dead.

Background: The “Endara Framework”

After years of U.S.-led economic sanctions against the military government of Manuel Noriega (1983-1989), in 1989 the U.S. invaded the country, destroyed the Panamanian military and took Noriega prisoner. The U.S. then helped arrange the victory of presidential candidate Guillermo Endara of the centrist Arnulfista Party. Endara was the logical choice: he had, in fact, won the May 1989 vote by a wide margin, but had been denied office by Noriega.

As president Endara tried to assemble a movement of disparate political forces, but friction soon arose, with the intransigence of the Partido Democrático Cristiano (Christian Democratic Party) (PDC) eventually leading to the exclusion of its leaders from the Endara coalition government. The PDC fell into a political death spiral and is no longer a major factor within the Panamanian political system. With the PDC out, Endara laid the foundation of a political mechanism,[1] setting up the alternation in office between his Arnulfista Party and the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (Revolutionary Democratic Party) (PRD). Although the PRD had begun as a left-leaning political wing of the General Omar Torrijos military regime (1968-1981), it has since morphed into a far less threatening centrist-oriented political party.

Source: www.bibliotecapleyades.net

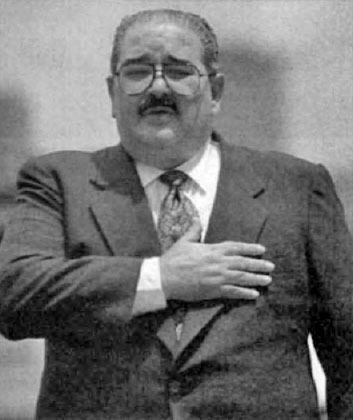

Under the pacted “Endara Framework,” the PRD took the 1994 election, bringing the presidency of Ernesto Pérez Balladares (1994-1999), a technocrat who had previously served in government during the Torrijos and Noriega years. Pérez Balladares accelerated the pace of the country’s conversion to free market economic policies. Social strains soon followed. Construction workers’ and teachers’ unions marched against the Pérez Balladares efforts to weaken labor rights and gut budgetary allocations earmarked for education. These protests contributed greatly to Pérez Balladares’ failed reelection bid in 1999, cutting against his efforts to amend the constitution to allow himself a second term.

The victor was Mireya Moscoso (1999-2004), the widow of former president (and caudillo) Arnulfo Arias (1940-1941, 1949-1951, 1968). Moscoso, a former hairdresser and political novice, tried mostly to avoid coming to any important decisions. When at length she made one, moving to oust the popular Director of the Social Security Administration, Juan Jované, protests erupted at once. The beleaguered Moscoso came to be seen by many as just out of her depth. This view was reinforced when she set off a serious international controversy by issuing a presidential pardon to terrorist Luis Posada Carriles, author of the bombing of a Cubana Airlines flight in 1976, killing all 78 aboard; bombings in Havana in 1997; as well as other acts of murder and attempted murder.

The PRD’s Martín Torrijos (2004-2009), son of General Omar Torrijos, won the presidency in 2004. In 2007, Martín Torrijos led Panamá into a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the United States (finalized in 2011). Under Martín Torrijos the Panamanian economy experienced rapid growth, driven especially by a construction boom which included the launching of the $5.2 billion USD canal expansion project. Also pushing economic growth was the infusion of streams of capital brought by the arrival of well-heeled élites from Venezuela and Ecuador, frightened away from their homelands by the election of the left-oriented governments of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Rafael Correa in Ecuador. Panama surged forward economically, proving exceptionally resilient to the 2008-2009 worldwide financial crisis. Martín Torrijos also took steps to mend international relations in the wake of the missteps by the Moscoso administration, and guided Panama’s successful bid for a coveted seat at the United Nations Security Council.

Yet Martín Torrijos was not able to build on these gains, and instead descended into a nasty internecine battle with PRD congresswoman Balbina Herrera, a mercurial politician with ties to Noriega, and Juan Carlos Navarro, the former PRD Mayor of Panama City. As the PRD squabbled, Martinelli, the opposition’s candidate, rode to victory in the 2009 presidential election.

Martinelli’s Panama

Although Martinelli cast himself as a political outsider, he was anything but. Before becoming president Martinelli had held several posts in Panamanian government. He had also campaigned for president before, and had learned enough to run this time on a vague platform of change, offending few enough voters to get himself elected.

Plus he had a little help from the U.S. government in the 2009 campaign. Martinelli’s election vehicle and political party, Cambio Democrático (Democratic Change) (CD) was probably too small to succeed against the Arnulfista and PRD political party machines, and U.S. policymakers worried that the leading opposition candidate, the PRD’s Balbina Herrera, was far too erratic to be acceptable. Determined to forestall a Herrera victory, the U.S. set the stage for a deal between the Arnulfistas and Martinelli, according to credible accounts.[2] The resulting election pact was enough to put Martinelli over the top.

Martinelli decided to leave foreign affairs to his Vice President, Juan Carlos Varela (Martinelli’s close ties to John McCain made dealing with the Obama administration pretty awkward), and embarked instead on a series of ambitious domestic projects, including the building of a metro system for Panama City. Martinelli moved aggressively to attract foreign investment by deepening the country’s free market economic policies, and his efforts were rewarded when international lending firms upgraded Panama’s credit rating. However, this achievement came at a heavy price, with a painful tax hike wrung from Congress only after some determined arm-twisting. Yet for all this, as Irene Giménez, a consultant with ties to the Panamanian business community, recognizes, “tax collection never met the expected and projected goals, which prompted the administration to ask for exceptions to the fiscal responsibility law [which keeps strict limits on deficit targets], increasing the deficit.” Martinelli had the worst of both worlds: he had solidified his reputation as a political bully who had stopped at nothing to ram through his tax increase, but in exchange he had not gained the actual increase in revenue he was counting on.

Martinelli’s actions earned him some powerful enemies. The Panamanian Chamber of Commerce began to push back, put off by Martinelli’s power politics, fiscal laxity and the emerging evidence of crony capitalism in his administration. Furthermore, surging teacher and worker unions organized around the Frente Nacional por la Defensa de los Derechos Económicos y Sociales Panamá (National Front for the Defense of Economic and Social Rights in Panama) (FRENADESO), demanding economic fairness.

The allegations of corruption became increasingly serious for Martinelli. One of the most exhaustively covered scandals was the Finmeccanica affair, where alleged kickbacks were doled out in exchange for government contracts. In a headline-grabbing twist, the scandal seemed to point directly to close associates of Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi. Martinelli fought back against all charges, becoming particularly pugnacious in his television appearances. Critics said Martinelli was becoming unhinged, but he could not be deterred. Doubling down, Martinelli turned his attention to the Supreme Court, attempting to pack the court with trusted allies who could be counted on to rule in his favor when the corruption charges arrived for adjudication.

On the domestic front the President launched a campaign to smash unions, igniting predictable anger from the rank and file. He made more enemies in early 2011 when his clumsy mishandling of a proposed amendment to modify the legal framework regulating the exploitation of mineral and energy resources in native lands managed to energize long-suffering indigenous groups. Ngobe Bugle, a coalition of indigenous peoples, moved into action, choking off the Inter-American highway for four days. After days of intense conflict, the administration finally backed off, at least for the time.[3] As protesters returned home, the government quietly renewed its plans to ramp up mining operations and build dams on the fragile ecosystems of indigenous land. Martinelli’s aggressive style even alienated his Arnulfista political partners, which he promptly sacked from government. Arnulfista Vice President Juan Carlos Varela, who could not be fired, joined the chorus of critics, focusing most of his energy in office on denouncing Martinelli.

As the days wind down for Martinelli, his administration is in disarray. Bitter accusations fly daily, the clang of the construction boom not quite drowning out the screaming matches within and outside the walls of government.

What’s Next for Panama?

Panama’s economic situation could be shifting, and fiscal difficulties may lie ahead. The Panamanian economy has grown in recent years, due above all to lavish spending on the Canal and other major public works projects. Yet the flow of government resources has failed to extend to public services like water, education, sanitation and garbage collection. Coverage is uneven and highly biased against rural communities and the urban poor who live in marginal communities around Panama City and Colón.[4]

Moreover, heavy borrowing has increased overall public debt by one third under Martinelli’s tenure. This has placed Panama in a highly exposed and dangerous position. The nation has a rather unique economy, built around international transport, international banking, and international free trade zones. For a country with such a small economy, Panama is extraordinarily connected to the rest of the world, and as such, it is highly vulnerable to the shifting vagaries of the international economy. If the Panama Canal expansion does not quickly produce large new cash streams, investor confidence may wane. As debts come due, Panama might not be in a position to pay.

Three Possible Election Scenarios for 2014

Outcome #1 Martinelli secures a victory for his party, either by running himself (which as of now, appears less likely given the constitutional impediments) or by finding a suitable stand-in candidate either within or outside the party.

A shrewd politician, Martinelli knows how to wait before taking the offensive. Indeed, some observers believe that the presidential primary within the CD was a sham,[5] and that Martinelli will ultimately be the one who decides who will run – if he hasn’t already. Martinelli has already pressured Guillermo Ferrufino, a popular but gaffe-prone cabinet minister, to back out of the race and run instead for mayor of Panama City (where he currently leads in the polls). In his stead, Martinelli recognized the victory of the pliable but relatively unknown José Domingo Arias to become his party’s presidential candidate … at least for now.

According to political observer Roberto Eisenmann, a Panamanian businessman and outspoken administration critic, the President is still considering other options. As Eisenmann sees things, Martinelli might decide to nominate Alberto Vallarino, a former Minister of Economics in Martinelli’s cabinet and current Vice President of the Arnulfista Party, in alliance with MOLIRENA, a smaller party which Martinelli controls. Vallarino has said that he is not interested, but if he changes his mind this could recreate the previous CD-Arnulfista alliance, delivering on Martinelli’s earlier promise that an Arnulfista would head the ticket this time around.[6]

To complicate matters further, Martinelli’s wife Marta Linares de Martinelli, niece of Arnulfo Arias (from his first wife, before Moscoso), is also an attractive candidate. Linares de Martinelli is very popular and it is altogether possible that she could form part of the ticket in 2014. Given her political lineage, she could prove to be a formidable contender, especially since her husband is willing to spend a lot of his considerable resources in the forthcoming campaign.

Outcome #2 The opposition PRD Juan Carlos Navarro gains the presidency, but Panama enters into a political stalemate.

The PRD hope would be that electoral success would buy them a post-election honeymoon, giving them time to craft a return to the “Endara framework” between the leading political parties. For now, the PRD does lead in the polls. However, the PRD could find governing Panama a difficult matter, especially as new political actors, including FRENADESO’s political arm, the Frente Amplio por la Democrácia (Broad Democratic Front) (FAD), are quickly rising to the fore. As Ignacio Iriberri, an activist and member of the FAD’s leadership puts it, “[The Endara framework] under the auspices of the Washington Consensus was very convenient for bourgeois groups, as traditional parties were subservient to them. But the present and immediate future remains dismal, especially in health, education, security, [etc…]. And the support to our registration drive demonstrates [how bad the situation is]: as of now 51,838 people have signed up [to become members of the FAD] in 50 days.” If the PRD wins, it will have to deal with an increasingly restive population, one that has no further patience with Washington Consensus-style economic policies.

Even worse for the PRD’s Navarro is a personal matter: Martinelli just cannot abide him. Indeed, Martinelli has already invested heavily in newspapers, radio, and even bought a TV station. Martinelli’s daily anti-Navarro twitter feeds are relentlessly abrasive. If Navarro wins, Martinelli won’t allow him a moment’s peace.

Source: www.tupolitica.com

Outcome #3 Arnulfista Vice President Juan Carlos Varela wins, and a new political framework is negotiated amidst increasing political tensions with the business class.

Already trailing in the polls behind Navarro and any CD candidate, Varela recently rattled the political establishment at the annual gathering of business executives by proposing a constituent assembly to draw up a new constitution. Although it remains to be seen if this is more ploy than promise, the unpredictability of a constitutional overhaul is deeply unsettling for the business community. If Varela is to succeed as a candidate, he may have to do so without their financial backing. And given Varela’s almost daily attacks on Martinelli, he can certainly count on the President’s determined opposition.

Conclusions

Voters will have the final say in 2014, but troubled times seem to lie ahead for Panama. Despite good GDP numbers, social discontent continues to rise, as profound social concerns and galling inequality remain unaddressed. As long as the economy performs well, popular dissatisfaction should be manageable. But no nation’s economy grows forever, and when Panama’s inevitably slows, popular forces will surely respond. No one knows where this might lead, but one thing is for sure: The Panamanian left is getting ready for prime time and grows stronger.

Eloy Fisher, Ph.D. Candidate in Economics at The New School and Dr. Ronn Pineo, Senior Research Analyst at the Council On Hemispheric Affairs and Chair of the Department of History at Towson University.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news or analysis on Latin America, please go to: Latin News and Rights Action

References:

[1] Fisher, Eloy (2010) Analysis: Martinelli’s Panama: Tilt or Tide… to the Right? COHA Issue Brief: https://coha.org/analysis-martinellis-panama/

[2] Miguel A. Bernal dice que ‘nunca hubo una alianza entre partidos’ La Prensa, 8/30/2011

[3] Fisher, Eloy (2012) Panama’s Critical Juncture: A Repeat of the Ecuadorian Debacle? COHA Issue Brief:

https://coha.org/panamas-critical-juncture-a-repeat-of-the-ecuadorian-debacle/

[4] Pineo, Ronn (2013) Panamá’s Troubled Path Forward COHA Issue Brief:

https://coha.org/panamas-troubled-path-forward/

[5] Primarias de CD: ¿farsa o realidad? La Estrella de Panamá, 2/25/2013

http://www.laestrella.com.pa/online/impreso/2013/02/25/primarias-de-cd-farsa-o-realidad.asp

[6] Eisenmann, Roberto Elecciones 2014 (I) La Prensa, 5/3/2013

http://www.prensa.com/impreso/opinion/elecciones-2014-i-i-roberto-eisenmann-jr/174874