The Other Nicaragua, Empire and Resistance

By Yorlis Gabriela Luna

ABSTRACT: Polarized opinions yield opposite views of the political conflict that occurred from April to July 2018. The hegemonic version told by the media depicts a crazed dictatorship murdering peaceful demonstrators. But this article recounts different experiences and different indignations. We use the term “soft coup” and place the people’s capacity for resistance in the context of their history of anti-imperialism.

KEY WORDS: Interventionism; social media; soft coup.

INTRODUCTION

For those who live in Nicaragua, it is well known that there is a dominant narrative about the political conflict that took more than 200 lives in 2018. The hegemonic version, repeated by human rights organizations and private media outlets from Managua to the halls of power in Washington, describes an almost complete “dictatorship” that, when faced with citizen protesters, responded with waves of violent repression aimed primarily at students and journalists, leaving hundreds of peaceful protesters dead. Therefore, the government no longer enjoys any popular support and a great coalition of social movements is just waiting for international assistance to ensure free elections so that the country can be liberated from a regime that has taken on and even surpassed the brutality of the Somoza dynasty (CENIDH, 2018). This is the version that has been broadly disseminated to the world by voices on both the Right and some who identify as Left.

This article seeks to disprove that narrative about events in Nicaragua in 2018, which, although meticulously constructed, is nothing more than a fabrication made a priori by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED)’s regime change laboratory, along with other U.S. institutions (BLUMENTHAL and MCCUNE, 2019). The main argument is that what Nicaragua experienced in 2018 was –as happened so many times previously in the nation’s history—a U.S. backed offensive. The difference was that this time it took the form of a so-called “soft coup” constructed on the basis of serious accusations and disinformation campaigns against “undesirable” governments. This essay also argues that in the context of Central America, Nicaragua poses the threat of a good example.

In early April 2018 the Nicaraguan government had a correlation of forces that, on balance, was considered positive. It enjoyed approval ratings above 70% and had won national, regional, and municipal elections with broad and growing majorities in 2011, 2012, 2016, and 2017. These elections had been recognized internationally by the Organization of American States (OAS) and other similar organizations as examples of broad citizens’ participation, particularly in terms of the engagement of women and young people in all stages of the electoral process. The latter is essential in a country in which a majority of the population is under 25 years old.

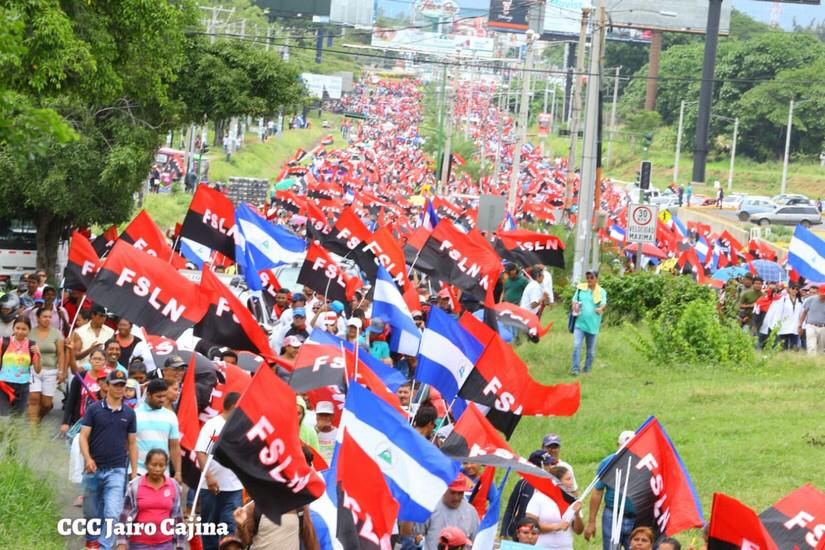

The governing party, the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN), enjoyed broad popular support with an organizational presence in all neighborhoods and communities. The economy had seen a decade of sustained growth that had lifted three out of every 10 people out of the poverty to which they had been condemned by three successive neoliberal administrations prior to 2007. During the 11 years of Sandinista government, Nicaragua had become one of the safest countries in the region, and indeed has the lowest homicide rate in Central America (the most violent region in the world that is not experiencing an armed conflict). Primary and secondary education became free-of-charge for Nicaraguan students, and free medical care was extended to a large part of the neediest population. Basic infrastructure was built (roads, piped drinking water, and sewer lines), which had been so lacking throughout Nicaragua’s history. However, after a decade of reduced social tension, the fabric of Nicaraguan society was ripped apart in April 2018. Within a few short hours, a political, media-driven, symbolic, geopolitical, and social class conflict raged.

Post-truth politics arrived in spectacular fashion in Nicaragua—starting with an unarmed conflict between a group of private university students who were protesting reforms to the social security system and a group of working class students who organized a counter-protest along the road from Managua to Masaya on April 18th. In less than 72 hours more than 100 million anti-government fake news messages were sent to social media users—in a county with a total population of only 6 million! (TRUCCHI, 2018) This provoked violent protests in two dozen cities.

A national and international media strategy was deployed around the events of April 19, 20, and 21, including the massive distribution of a certain version of those events, as well as their broader historical, social, and political context (KAUFMAN, 2019). The truth became disputed territory, since much of Nicaragua’s NGO complex is funded by the US government, including the Permanent Commission on Human Rights (CPDH) and the Nicaraguan Association for Human Rights (ANPDH); indeed, the latter was founded in Miami and funded by the US Congress in 1986 to clean up the image of Ronald Reagan’s dirty war waged by the CIA to overthrow the Sandinista Revolution. “In fact, several privately-owned news media in Nicaragua, including La Prensa, and others commonly cited by international news agencies, have been funded at some point by the National Endowment for Democracy, or NED (BLUMENTHAL, 2018). The NED has been linked to regime change operations elsewhere that seek to grab the public opinion of an entire country overnight in order to remove a government deemed undesirable by the United States. Using its client media outfits and human rights organizations that repeated one another’s fabrications without carrying out rigorous investigations, the US government was able to establish an echo chamber of propaganda and control the narrative on Nicaragua. In its own online publication, the NED congratulated itself for “Laying the groundwork for insurrection in Nicaragua” (WADDELL, 2018). And the U.S. government is currently implementing a policy of economic sanctions against Nicaragua, threatening to revive the extreme poverty that had practically been eradicated in the country, while weakening the national economy.

This article will first analyze the construction of intangible territory in Nicaragua having to do with historical revisionism, pejorative messages, and threats that together constitute a strategy to hinder resistance to the rupture of the democratic order in the country. Second, it will explore the dispute over tangible territory, since for 90 days starting on April 18, right-wing forces built physical roadblocks on all of the country’s highways to demand the “total surrender” of the government (FONSECA TERÁN, 2018). The roadblocks paralyzed the circulation of persons, sank the economy, and became scenes of violence including rape, torture, murder, and the burning of human beings (ZEESE and McCUNE, 2018)—primarily those identified as Sandinistas.

As events unfolded, the strategy evolved from one of psychological pressure exerted over social media to a violent and armed offensive—from peaceful protests with rocks and homemade mortars to fully armed protests. During June and July, a large segment of Nicaraguan society mobilized physically to protect their neighborhoods, schools, homes, public infrastructure, and clinics, unraveling the attempted soft coup. However, the international media have not shown any interest in that story. The overwhelming majority of them continue to push the narrative of a population that rose up against a repressive government. This article gives a voice to The Other Nicaragua.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF NICARAGUA

Central America’s geographical position, the extraction of natural resources, the exploitation of cheap labor, and the potential to build an inter-oceanic canal captured the interest of the United States. As a result, the region’s history has been bathed in blood and resistance, ultimately producing the desperate migrant caravan from the northern triangle of the isthmus, which is nothing more than the offspring of U.S. imperialism.

Nicaraguans have been virtually absent from the migrant caravan. That is no coincidence. It is the result of a complex history in the Central American country that has had the most armed conflicts, punctuated by brief periods of peace, and the one that has attracted the most geopolitical interest and thus suffered the most interventions. It is also the country in which the dynamic of U.S. imperialism has produced longstanding anti-imperialist movements (WILLSON and McCUNE, 2019). Since the American mercenary William Walker declared himself president of Nicaragua in 1856, imposing slavery and declaring English to be the official language of the country in order to gain the support of the southern U.S. slave states, there has been resistance to American economic and military aggression in Nicaragua. A byproduct of this is a society that categorically rejects U.S. intervention (NÚÑEZ, 2014).

During the Spanish-American War the United States reclaimed control over the Caribbean Basin and renewed its interest in Nicaragua’s geographical location. The U.S. financed a Liberal rebellion against President José Santos Zelaya, who had introduced liberal reforms and taken a stance in defense of national sovereignty. The United States managed to overthrow Zelaya and impose the Chamorro-Bryan Treaty with the complicity of the national oligarchy. This treaty gave the United States exclusive rights to build an inter-oceanic canal through Nicaragua and a U.S. military base in the Gulf of Fonseca, and granted the U.S. the right in perpetuity to invade Nicaragua over political matters (RAMÍREZ, 1988).

The U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua militarily from 1912 to 1926 to prop up Conservative President Adolfo Díaz, a former manager for a U.S. mining company who needed foreign intervention to stay in power (RAMÍREZ, 1988). The same year that the Marines left, an armed conflict broke out with Liberal armies demanding the ouster of Díaz. So the Marines occupied the country once again and a peace agreement was signed stipulating that Díaz would remain in office until the 1928 elections and that the Marines should stay. This was the context of the Constitutionalist War in which Augusto César Sandino was one of the generals who refused to lay down his arms.

Sandino had come from an indigenous community and had worked as a peasant, a merchant, and a worker; he had lived as an immigrant in other Central American countries and Mexico. He instituted guerrilla warfare against the Yankee invaders and enriched the military tactics of the indigenous Nicaraguan resistance to the colonialism and neocolonialism of the heirs of the Spaniards. Sandino was anti-imperialist, nationalist, and Bolivarian; he advocated an economic and social model of cooperatives. Sandino’s struggle against U.S. intervention was also carried out by unarmed men, women, children, indigenous people, Afro-descendants, and peasants. They demonstrated a tremendous capacity for sacrifice, going without food, clothing, and weapons, but full of love for Nicaragua and its dignity. Sandino was scorned by both the Catholic Church and the local bourgeoisie (NÚÑEZ, 2015). Towns and cities were surrounded and bombed in order to cut Sandino’s army off from supplies and its social base. Women were raped and entire families were tortured and thrown out of their homes and off their land. The Yankee army sowed terror in the population, which generated contempt for it and helped recruit people for Sandino’s army (DOSPITAL, 2013).

The U.S. troops withdrew in 1933. In 1934, on orders from the United States, Anastasio Somoza García assassinated Sandino, launching one of the bloodiest dictatorships in Latin American history, which lasted more than 40 years. He enjoyed the support of the National Guard, a new military force trained and created by the United States (NÚÑEZ, 2014).

In the 1960s and 1970s, Carlos Fonseca Amador took up the mantle and ideals of Sandino and trained a new generation to fight against Somoza and his National Guard. Inspired by the Cuban revolution, he and other young people founded the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN), a military and political organization that triumphed on July 19, 1979. That year, the Sandinista People’s Revolution, following the ideals of Sandino, drastically changed the Nicaraguan landscape, especially its economic structure. However, during the 10 years of the Revolution, Nicaragua confronted and resisted an economic blockade and imperialist aggression from the United States, including the creation and funding of a counter-revolutionary army. These Contras, as they were called, sowed terror in the peasant population, along with economic sabotage, drug trafficking, and a brutal war (BLUM, 2005).

The defeat of the FSLN in the 1990 elections ushered in a counter-revolutionary, neoliberal government, which sought to eliminate the legacy of the Sandinista People’s Revolution. One tactic was to change the revolutionary names that had been given to places and to erase revolutionary symbols. There was a cultural and ideological offensive aimed at destroying the fabric of revolutionary social organizations and eliminating any resistance to neoliberalism. This also led to the dismantling of the revolution’s social achievements, which resulted in far-reaching changes in the economic, political, and social structure. Several neoliberal structural adjustment packages were imposed on the population, major segments of the economy were privatized, government spending was cut drastically, and a system of NGOs was imposed to mitigate and buffer the disasters caused by all the privatization (NÚÑEZ, 2014).

All of the above caused a dramatic reduction in the quality of life. There was a 46-point drop in the Human Development Index; precarious employment increased along with unemployment; and there was an exodus of peasants from their farms. Outsourcing and informal employment characterized the economy, while extreme poverty, social inequality, and violence increased (NÚÑEZ, 2015). In 2007 the outlook was complex and devastating. This social catastrophe was added to the destruction caused by the wars for liberation, and the thousands of people orphaned and disabled by the war.

From 2007 to 2018, with the Sandinistas back in power, the number of undernourished people in the country fell by half; access to free education and health care was ensured for rural and urban communities; maternal mortality was reduced by 60% and infant mortality by 52%; migration decreased; the percentage of the population with electricity in their homes increased from 54% to 95.5%–including 2.9 million rural inhabitants—while 70% of the energy matrix now comes from clean, renewable sources. The quality of life and life expectancy of the Nicaraguan people have both improved (ACOSTA, 2019).

Nicaragua currently has the lowest crime rate in Central America, the best domestic roads, and is ranked fifth worldwide in terms of women’s participation in public life (ACOSTA, 2019). The government was re-elected in 2016 with 72% of the vote, and it regularly polls at 60-80% approval rates (FONSECA TERÁN, 2018). This government is a departure from neoliberalism in terms of economic model, reinsertion of the State into the economy, and investment in the social services infrastructure. It has restored dignity to the living conditions of the overwhelming majority of Nicaraguans. This model appreciates the values of the family economy and supports it by strengthening the cooperatives and self-employed people who account for 65% of employment in Nicaragua. These small businesses have made it possible to reduce food imports, and the country currently produces 85% of the food that it consumes (CES, 2018).

These social breakthroughs have not been free of contradictions or mistakes, such as the alliance with the private sector and the Catholic Church until April of 2018. It was particularly erroneous to fail to deepen the social model and encourage more people’s participation in decision-making. This is how one can build an alternative to capitalism in which new human beings and new territories are formed. Rather than forcing the limits of the system of domination, a new society must be built to overcome the systemic crises of capitalism (FONSECA TERÁN, 2018).

AN UPRISING “MADE IN THE USA”

This section will review the period of preparations for the events of April 2018 and the influence of the United States’ government, particularly its financing of social networks and media outlets. At the beginning, from April to June, these networks and media outlets were capable of fooling a significant portion of Nicaragua’s youth and general population. One year after the events, they continue to have sway over the international media.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has openly declared that the objective of the U.S. is to destabilize and change the governments of Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua—the countries he deems to be the axis of evil in the hemisphere. In order to achieve this objective, for years the U.S. has been funding the local media and a network of human rights agencies to construct their version of the truth (FONSECA TERÁN, 2018). In May 2018, the NED journal Global Americans published an article of unabashed candor in which it congratulated itself for “Laying the groundwork for insurrection” (WADDELL, 2018).

The NED was created in 1982 as a non-profit institution and appears in the annual budget of the State Department under USAID to channel Congressional funding and offer international political assistance to national political groups that serve its geopolitical interests. In 1990, the NED spent $16 million to influence the elections in Nicaragua, founding the anti-Sandinista opposition. Once it achieved its objective (of ousting the Sandinistas), it never stopped working with “promotion of democracy” efforts. It has had sizeable budgets and used its ample experience with regime change operations in April 2018 in Nicaragua (KAUFMAN, 2019).

In 2007 the U.S. redesigned its strategy since the Nicaraguan political parties aligned with its policies had lost significant prestige due to their high levels of corruption (one of the highest in Latin America at the time), their neoliberal policies, and the disdain the governing classes openly displayed toward the working class. For this reason, the U.S. created more efficient ways to fund and control organizations to give them the appearance of objectivity. They depicted themselves as aligned with social policies—beyond politics—to give the appearance of “independent” civil society with a human face and without ties to a particular political party (Blum, 2005).

The NED publicly spent $4.4 million since 2014 to build up the opposition in Nicaragua. For 2017 alone it was more than $700,000. The funding targeted human rights organizations and the media. It was also for social media, with the idea of training young people for “political advocacy,” (WADDELL, 2018, p. 3) fostering debate and generating information about crime and violence (BLUMENTHAL and McCUNE, 2019).

The funds were distributed to non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The NGO Let’s Make Democracy (Hagamos Democracia) received $525,000 in NED funding from 2014 to 2018, and the Institute of Strategic Studies and Public Policy (Instituto de Estudios Estratégicos y Políticas Públicas—IEEPP) received at least $260,000 from the NED. In 2018, the USAID budget for training civil society was $5.2 million (BLUMENTHAL and McCUNE, 2019). For years the organizations built and supported by the NED have received generous million-dollar budgets to “lay the groundwork for insurrection in Nicaragua” (WADDELL, 2018, p. 3). They used scholarships to learn English, diploma programs, graduate studies, and courses with enticing names like “democracic values, social media activism, human rights and accountability”, at exclusive private universities to attract and lure young people. The scholarships were publicized on social media, at public and private universities, and in youth base communities of the Catholic Church. The young people applied online. This author conducted some interviews in 2019 that reveal how alluring these courses were:

I heard about it through the youth pastors at the Cathedral. All youth pastor leaders had to apply and they told me to apply on social media. They told us it was an open consortium in which IPADE, the embassy, USAID, IEEPP, the American University, (St.) Thomas Moore University, and American College all participated. Once you were there, they told you about investment funds, international scholarships to the U.S., internships and volunteer opportunities, international travel. For them to finance you in big programs or entrepreneurship opportunities, you had to be part of the consortium. They would say it was apolitical and that mostly it was for development, but once you started a program, they monitored you. (Interview of ALP, February 11, 2019)

It is estimated that 2,000-5,000 young people were trained as democracy promoters, influencers, community journalists, and other titles (BLUMENTHAL and McCUNE, 2019). The courses included project preparation, reporting, videography, photography, social media, website creation, and fundraising:

We participated in competitions and whoever had the best initiatives would get a financial reward. And what I saw in April was that the most successful ideas on the networks during their programs were some to paint posts. That was the idea to paint posts in blue and white. In April they also would put you in touch with sponsors outside the country to implement your own impact projects. At other times they would draw you in with community projects from IPADE and other NGOs that made the links; in the churches they had a lot of young people. These were the same ones who took charge in the church… the church would give you a recommendation, the first interview to belong to the workshops you had to give references. When I applied, I put down several from the church and another who had participated. I realized that it was a competitive space to capture young people. The kids who excelled were the ones who didn’t appear to be political. There were scouts, environmentalists, even kids from the Sandinista Youth. They would give you some assistance, a per diem, meals at hotels, transportation costs. They wouldn’t pay you, but they paid for your costs and courses and give an endorsement for you to look for work in those same NGOs. (Interview of DAR, March 7, 2019)

What was so appealing and attractive to the young people was the possibility of taking international courses, diploma programs, and international scholarships with no cost to them:

Foreigners showed up at every workshop and went around supervising. Sometimes they even did the training—foreigners from Spain, Chile, the U.S.—the U.S. ambassador always came to the graduation ceremonies. First they did it by locality, then by region, and country. The courses were always taught in expensive hotels and elite locations. (Interview of PAM, April 5, 2019)

Often these kids got to see places like Selva Negra in Matagalpa, the hotels in Bolonia in Managua, the Hotel Hex in Estelí, Café Iguana in Juigalpa. There are even kids who were taken outside the country. (Interview of DAR, March 7, 2019)

As the soft coup operation got underway, most of these young people were activated:

You don’t think it’s for such evil purposes, but you somehow feel deceived. It felt as though they were preparing an army for combat. Then you would see the kids who were in those courses, the leaders, and you felt duped. (Interview of FML, February 6, 2019)

This training process was the key component for spinning a web of young people with all the tools of communications and networking, trained and prepared to carry out actions in the streets that would have great symbolic impact. Many of these young people were poor or were from the lower or upper middle class. It was a successful training process since they developed a sense of “pride,” belonging, and “group identity” by participating in these programs. They wound up aligning themselves with the foreign interests. The education they received about the political and social reality of the country was removed from its historical and political context. This served to generate partial social consciousness. They did not analyze the history of Nicaragua in the regional political context, nor was there any critical thinking about the training process itself. The objective was to “de-ideologize” them and put their class consciousness to sleep, along with their sense of the historic moment; their subjectivity was colonized. It was reactionary training disguised as revolutionary training.

Young people are the most vulnerable because they are more drawn to the mind-numbing culture industry (for entertainment, fashion, art, advertising), with all of its signs, symbols, and well-constructed psychological manipulation, which fosters a mentality of individualist, banal, and superficial consumerism. This is why the most prominent representatives of the entertainment industry in Nicaragua (artists, super models, designers, and influencers) became the “iconic symbols” of the April protests. During an interview, the parent of one young person who participated in the roadblocks and the takeover of public universities said:

First she won a scholarship to study English at the U.S. Cultural Center, and from there she just went from course to course. She never told me anything, just that she was going there… but she was changing and she became very self-centered, very arrogant. She thought that her analysis of the country was the only truth. She became so selfish and proud that she is no longer my humble daughter. She also became very consumer-oriented and no longer accepts that she is poor. (Interview with AAS, January 11, 2019)

The strategy particularly targeted millennials because they are more susceptible to fake news and have grown up benefiting from the government social programs in education, health, and sports. They do not remember the neoliberal period of the 1990s or their country’s history.

Over the course of two to four years, these young people built very strong apolitical social networks locally and nationally. They interacted with thousands of people about buying and selling things, destinations for partying, and local entertainment. For example, they used such Facebook pages as “Masaya Gossip and More,” “Chontales Entertainment,” “Eastern Market,” and “Buying and Selling Nicaragua.” Once all of these networks were established, they just had to wait for a key moment to activate them. This was tested with #SOSINDIOMAÍZ when they tried to blame the government for the fire in the Indio Maíz forest preserve. The next was #SOSINSS when reforms to the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute were announced.

THE OFFENSIVE AGAINST INTANGIBLE TERRITORY

During the first few days of turmoil, Facebook became the main source of fake and real news in Nicaragua. Hundreds of accounts purchased ad pages with very disturbing scenes of violence, many which were later determined to have come from El Salvador, Honduras, and even countries as far away as Paraguay. But the impact was that young Nicaraguans shared these Facebook ads which, once shared on Facebook, no longer appear as paid advertisements and looked like all other shared content. This is how a lot of false news reports were disseminated throughout the country, such as reporting deaths that had not occurred and even accusing the government of installing snipers to kill civilians.

This explosion of digital information stirred up a sense of solidarity among the youth and society for the “defenseless protesters” and against the government, which had been denominated as “the dictatorship” on Facebook. This kind of narrative holds a lot of sway in Nicaraguan society, because of the long and heroic struggle of students against the Somoza dictatorship. It did not matter so much that it was untrue; what mattered was that they had achieved the capacity to repeat such messages hundreds of thousands of times, through all media outlets available to the Nicaraguan people (HENDRIX, 2018). Among the scenes posted there were fake photographs and photos from other countries and other times, along with manipulated videos and still shots, and a very sophisticated campaign spread them through Facebook ads (TRUCCHI, 2018).

Social media was used on such an overwhelming scale to create a state of shock, panic, and paranoia that absurd reports—hard to believe for the Nicaraguan context—became “the truth.” For example, they said that cities were being bombed and that small planes were spraying the major cities with agrochemicals; that Cuban snipers had come to Nicaragua; that Russian drones were attacking young protesters, among other messages which both before and after were and are patently absurd, but at that time managed to mobilize a certain segment of the youth to protest.

The dynamic of social media is such that what goes viral today loses meaning and importance tomorrow. Once the lies are disproven, it no longer matters because the feelings have been spread and violence has been generated. In communications this is called a “false positive.” Some examples are: as the protests began, recordings of young people came out on WhatsApp[1] in which they said, “we are college students and there is a death at the Central American University (UCA).” There were videos of young people screaming, “They are attacking us, the police are attacking us, there are so many wounded!” Later it was discovered that no one ever died at the UCA, and when one looks at the videos it is apparent that the narrative did not correspond to the images.

The conflict was managed through the signifcant dominance of Facebook and WhatsApp. This is where the strategy of stealing intangible territory—Nicaragua’s Sandinista heritage—was implemented. For example, all the student organizations financed by foreign NGOs were given names associated with the date April 19, despite the fact that the protests had begun on the 18th and the worst violence did not begin until the 20th. The importance of the 19th is well-known in Nicaraguan society because the 19th of July is the anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution. Thus, “occupying” the 19th was an attempt to confuse members of the Sandinista Party and prevent them from resisting regime change. On social media, the opposition groups urged people to go viral with the phrase, “It’s no longer July 19th, now it is April 19th.” They even mentioned this in their public speeches, t-shirts, and propaganda.

By the same token, during acts of violence or street vandalism, right-wing groups sang historic songs of the FSLN while they burned the party’s red and black flag, or while they destroyed or painted over Sandinista monuments, replacing the red and black with the blue and white of the national flag. For weeks, most of the streets in all the cities of Nicaragua were painted blue and white—and this was often done by people hired by the Catholic Church, the right-wing parties, and some families of the local oligarchy. All of these things—the use of symbolic dates, using Sandinista revolutionary songs in their protests, and abruptly changing the colors seen by the public—are tactics mentioned by Gene Sharp (1993). He talked about the use of signs and symbols in his books on “soft coups” which were followed by the organizations funded by the NED to carry out color revolutions in Eastern European countries, such as the former Yugoslavia (BLUMENTHAL and McCUNE, 2019).

These actions marked a new stage in the strategies to seize control over territory in Latin America. Another tactic the opposition used throughout Nicaragua was roadblocks, which also served the purpose of conquering tangible territory. The idea was to mimic the barricades used during the popular uprising against Somoza in 1979. The same has been done in Syria, when the opposition jihadists, with the assistance of western intelligence services, used roadblocks to establish “no go” zones in which neither the government nor the media could enter, allowing the jihadists to create their own narrative about the conflict which did not reflect reality (BLUMENTHAL, 2018).

It was a well-designed, planned, and organized physical and ideological attack in which physical spaces, objects, systems, and power relations remained immersed in tangible and intangible territories (MACANO, 2009). The roadblocks converted public spaces into areas in which the opposition used violence to control the circulation of people, vehicles, and supplies. They paralyzed international commerce, made it possible to burn and loot public and historic buildings, and torture, burn, and publicly murder people known historically to be Sandinista. This resulted in the weakening of the national and local economies, the loss of 100,000 jobs, and the loss of US$182 million worth of government infrastructure, schools, hospitals, and historic sites that were burned, looted, and completely destroyed (ACOSTA, 2019). It also led to a reduction of the national government budget and left people dead, wounded, and psychologically traumatized. It left thousands of Nicaraguan families divided and broken.

The international media served as an echo chamber for the narrative created by the media circus and spread through thousands of fake accounts and by citizens who were either dissatisfied with their government or confused. Through these accounts the regime change forces sought to control the intangible territory of day-to-day ideas and people’s thoughts and feelings (MACANO, 2019). They particularly wanted to control the attitudes of the youth toward the FSLN by confusing and polarizing society.

The communications strategy of the groups funded by the NED consisted of stirring up hatred and intolerance between two sides in Nicaragua: part of the population was indignant about the “murderous” government, and the other side was terrorized and confused. They used hatred for the FSLN as an escape valve for personal and social frustrations.

People who took opposite views of the conflict disagreed as to whether there were right-wing armed groups attacking the homes and families of Sandinistas throughout the country. The researcher Enrique Hendrix (2018) shed light on this when he published the results of his case-by-case analysis of the circumstances surrounding 167 of the deaths from the conflict reported by the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (CENIDH). He concluded that CENIDH had reported 4 repeated names, 14 names with incomplete information, 19 people whose deaths (including car accidents, suicides, etc.) were unrelated to the political conflict, 35 bystanders killed in violence not attributable to either opposition or pro-government forces, 51 people who were directly involved in opposition actions, including protests, shoot-outs and roadblocks, and 44 people killed by opposition attackers. However, this latter group of victims was never reported on by the private media companies.

However, in Nicaragua, the best predictor of someone’s opinion on the matter is one’s social class. People from working class neighborhoods, who don’t own cars, and who experienced firsthand the roadblocks, violence, and political persecution—even if they are not Sandinista supporters—tell what they experienced. Those from the middle and upper classes, who from the comfort of their homes in gated communities, encouraged the violence or repeated news reports of questionable veracity, generally tend to have another opinion and repeat the discourse about a dictatorship.

In this case it was one’s roots and class consciousness, rather than one’s ideological background that made the difference. Many people who were counterrevolutionaries in the 1980s—people from poor neighborhoods or the countryside, peasants or workers—were not fooled by the media onslaught. Other people who in the 1980s were emissaries of the revolution from the middle and upper classes, and who are now linked to the NGO sector, had a different position. The ideological territory was demarcated, labels disappeared, and people’s principles, values, and identities became apparent.

Terror has been used as a tool of empire throughout Central America’s history. The Spanish Conquistadors used it against rebellious indigenous people. Then the U.S. Marines used it in their invasions of Nicaragua. Latin American dictators used it in the twentieth century, the contras used it in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and the Nicaraguan opposition used it in April of 2018:

Terror has always been used for conquest to alter people’s perceptions of themselves and the group they belong to; force has been used to alter and deform the consciousness of individuals in terms of being, thinking, and doing. (Valenzuela, 2009, p. 204)

In such a scenario, the parties to the conflict were not clear. The government called upon the demonstrators to sit down and work out an agreement in what was called the National Dialogue. Representing the opposition protesters were: two Aspen Institute fellows, María Nelly Rivas, the representative of Cargill in Nicaragua, and Félix Maradiaga, the Director of the IEEPP (ZEESE and McCUNE, 2018); Michael Healey, representative of UPANIC, a conglomerate of single crop agro-exporters; and other people from families that have been prominent over centuries of Nicaraguan history, such as Juan Sebastián Chamorro, who bears that iconic surname of the Nicaraguan oligarchy (NÚÑEZ, 2014).

These people said they were demanding social rights and claimed they were backed by “grassroots” organizations, such as the anti-canal movement financed by Hagamos Democracia and the NED (ZEESE and McCUNE, 2018) and demanded the immediate removal of the president. But they represented big money in Nicaragua and multinational interests aligned with the U.S. During an interview, a construction worker in the informal sector expressed his perception of the Dialogue:

The rich do not care about the poor and never have… Most of the people representing the Civic Alliance[2] in the National Dialogue were white, tall, and well-spoken. Their speech sounded learned and they represented unknown organizations… On the government side we saw everyday people with ordinary last names, they were black, olive-skinned, tall, fat, thin. Their speech was ordinary and their organizations were familiar… . (Interview of TLD, February 11, 2019)

There are grassroots organizations with long histories of social struggle, such as the teachers’ union, the transportation workers, farm workers, and nurses unions, and others—all who had resisted the neoliberal governments for 16 years and are well-known for their long social struggles in which they held national strikes and sometimes paralyzed the country in the 1990s. These are the authentic social movements that mobilized the population, making it possible for the FSLN to return to power. All of them spoke against the attempted coup. Cooperatives of taxi drivers and peasant farmers likewise supported the government during the National Dialogue. Very importantly, the National Student Union of Nicaragua (UNEN) stood firm against the coup throughout the conflict. As a result, it was the target of repression and a slander campaign by the armed right wing.

These grassroots organizations were aware of the strengths and weaknesses of their government and took a stance that violence was not necessary, nor was it necessary to destroy the economy or seek foreign intervention or U.S. sanctions to bring about regime change. These organizations represent the popular economy, which is the true productive economy in the country (NÚÑEZ, 2015).

The dialogue made no progress and the violence continued. Two months later in different parts of the country, the population created its own alternative forms of communication to counteract the dominant narrative. People took back social media and built their own geographical trenches to defend their neighborhoods and public spaces as alternative responses to the violence that was spreading throughout the country.

BARRICADES, TERRITORIAL LEADERSHIP, AND TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE RESISTANCE

The people resisting the coup attempt revived the concept of barricades from the 1970s. These barricades were places of collective security with defined schedules and roles to protect territorial security. They brought together young people, old people, street vendors, market vendors, unemployed people, peasants, retirees, government workers, housewives, former members of the military—but above all workers in the popular economy and residents from all over. People were not united by ideology, but rather the need for collective protection and their opposition to the violence and abuses committed at the roadblocks.

The local population took charge of logistics in these spaces because the geographical roadblocks prevented people from getting access to food, transportation, and logistics. The basic tasks of these organized spaces in the neighborhoods included physical protection of the neighborhoods and government institutions, creating spaces that were free of hatred and discrimination, and sharing stories and communicating on an individual basis about what was happening. The barricades sponsored cultural activities and prayer sessions and established a presence on social media. Generally speaking, they were located in someone’s house at the entrance to a neighborhood and around government institutions or FSLN offices. Through everyday life they reconstructed the truth and redeemed its value, and with this they reconstructed the historical memory of these territories. This proved that forms of territorial resistance “never occur in the abstract; they begin to occur on the ground and as a function of the conflict established by the oppressors” (SANTOS, 2009, p. 385).

Table 1 – Disputed territories and strategies resulting from the political conflict in Nicaragua that started in April 2018

| Groups in Conflict / Disputed Territories | Church-oligarchy- media companies-U.S. embassy axis | Government-party-neighborhood-peasant axis |

| Tangible ● Streets ● Infrastructure ● Schools and universities ● Transport ● Funding |

● Destruction, looting, and burning blamed on government while no private sites were ever affected ● Sites used for torture, kidnappings, and murders ● Charging expensive tolls to get by each roadblock ● Using international funds through NGOs, USAID, and NED ● Paralyzing government functions and interrupting daily life ● Uniform actions throughout the country |

● Protection of physical spaces in working class neighborhoods ● Tolerance and respect ● Freedom of movement ● Use of paths between farms to send food to towns ● Logistics handled by the local residents of each place (to provide coffee, water, beans, tortillas, food, blankets, etc.) ● Allowing everyone to function normally, with nothing hindering them ● Creative actions in each territory |

| Intangible ● Human rights ● Safety ● Historic memory ● Legitimacy ● Identity |

● Freedom of the press ● Maintaining the roadblocks ● Lying and fabricating data, contexts, and co-opting symbols ● The oligarchy, middle class, and young people alienated from their social class ● Dismantling of the social fabric |

● Rights to health, education, housing, etc. ● Recover peace ● Redeem local identity and the historic values of the FLSN ● The working class in neighborhoods and communities ● Strengthen community ● Creativity and new cultural forms, symbols, songs, etc. |

Source: the author

The ones who were “capable of changing the landscape and the terms of the conflict through daily and collective action” (SANTOS, 2009, p. 386) were the longstanding members of the FSLN. In many cases they set aside personal disagreements and offered all their organizational experience, moral strength, and historical consciousness to change the correlation of forces. These spaces were filled with great-grandparents who had fought with Sandino or against Somoza, grandparents who had defended the revolution in the 1980s, parents who had struggled against neoliberalism. Together they conducted collective security watch day and night over trucks, neighborhoods, threatened homes, and offices. They passed along food and strengthened the intergenerational dialogue, social cohesion within territories, interpersonal communication, and local identity.

There was a generational dialogue: the old guard of the Sandinistas showed their mettle to the young people who had often treated them with disrespect. They regained prestige and recognition in the territories as people realized that the outcome of the territorial dispute rested on their shoulders. These men and women shared their organizational, ideological, and leadership experience with the young, who in turn shared their energy and social media skills. The different generations learned from each other. It is noteworthy that they also used social networks to unravel the lies, clarify things, explain, and engage in dialogue.[3]

These historic combatants revealed in interviews that they were never confused about the social and political situation:

We Sandinistas have an awareness that the current reality can change… over my life I have learned that everything changes, but the change should be geared to helping the poorest of the poor, social programs… You aren’t just a Sandinista until age 55 and then you retire and stop fighting. You have to fight for Nicaragua with social consciousness until you take your last breath. If you understand what moves society and the social forces, you don’t feel immobilized or demoralized. You feel certainty that everything can be changed. (Interview of AA, April 2, 2019)

I joined the Frente in 1978. I was a shoemaker. In Juigalpa I joined with Ahmed Campos. I survived prison and Somoza’s torture, and the contra massacres. Three times I was kidnapped by resistance commandos. I have seven bullet wounds in my body and I survived 37 contra ambushes… and I couldn’t let what we had paid for with so much blood since ’79 to just be taken away from us. The enemy is the same, the tactics are the same. The bravery of others—their principles and values—this gives you courage and you don’t mind dying for your homeland. We have to teach our young people to love their country. (Interview of CHA, April 2, 2019)

Nicaragua’s history has been tough. The methods change, but it has been the same enemy since Sandino. The hardest thing was not to lose your cool. It was a psychological war just like the contra war. They are the same methods. (Interview of CAR, January 15, 2019)

In interviews, two young street vendors who had participated alongside the historic leaders of the FSLN said that they felt a need from within to participate:

Look, my Dad died in the war of the 1980s. I was just four months old. That’s why I went out to defend our people, to follow his ideals. There are people who are poorer than me, and I have seen how they always get help—education, health care. But also, I was getting harassed by the roadblock people because I am Sandinista. They threatened me and came to my house and shot it with bullets. So I felt safer at our barricades. I was afraid but I felt closer to my Dad. (Interview of JAR, 28 years old, December 5, 2018).

I was afraid, but calm at the same time. I felt that it was a struggle because it is not fair for them to just remove the president like that. I felt that it was necessary, that we had to fight. You can’t pay with bad currency. I learned a lot from the old people. (Interview of MAG, 22 years old, November 1, 2018).

At that time it was very dangerous to be recognized as Sandinista or to associate with Sandinistas. For this reason, people who held economic and political influence in the territories simply retreated, ceding ground to those who were interested in the truth. Even many apolitical people were bothered by the discrepancies between what was reported in the media and the reality they were living through. In the end, they wound up marching with the Sandinistas. The political crisis turned into an unprecedented process of political education in real time for thousands of young people. That is why in 2018 the FSLN got more people into the streets than ever before in its 60 years of history. The popular economy was a critical part of this. It kept people from running out of supplies of the most basic things, helped regain mobility, food, employment, continuity, and normal life for the Nicaraguan people.

There are visible similarities and parallels among these three key moments in Nicaragua’s history: Sandino’s struggle, the contra war, and the attempted soft coup of April 2018. First was the participation and financing of the United States government, the Catholic Church and the local oligarchy, the use of terror, and the use of the media to amplify the hegemonic narrative. This was matched by the territorial resistance of the working classes and their steadfast alliance with the resistance to a coup, and everyday Nicaraguans’ capacity for sacrifice, spirituality, and dignity.

The U.S. government and its local partners tried to eliminate the legacy of Sandino, the Sandinista government of 1979, and the current Sandinista government—still supported by a broad segment of the population—as more than a political actor. They tried to erase them from the minds and hearts of people. During these three times in history the Sandinistas were disparaged and deliberately misunderstood. Their slogans were coopted and their mistakes overblown, while our enemies lied and distorted the facts. They tried and keep trying to strangle us economically. At those three times in our history the blood of Nicaraguan brothers and sisters was shed on both sides of the conflict. But the true Sandinista values and mystique revealed themselves, along with the people’s creativity.

CONCLUSION

The truth about what happened in Nicaragua in 2018 is coming out through the cracks and fissures in the dominant narrative, but this has little impact compared to the destruction and spiritual pain that has our people in mourning. However, the lessons learned will remain for many generations. The Nicaraguan people were political actors and essential protagonists in changing the correlation of political forces from April to July 2018, from community organizing and communications to social media, where a battle for values, identity, and individual and collective histories was fought.

The dialogue between generations and the handing down of values to the youth, from the leaders and historic members of the FSLN, all changed the power relationships. Values and an identity must be instilled in human beings if they are to build new realities and become capable of resisting the dominant system. Dialogue and the ushering in of a new generation are essential for defending our territory from the new strategies for systemic control.

Only Nicaraguans can decide on Nicaragua’s future, without outside intervention, and without sanctions that make the poorest of the poor suffer and damage the country’s vulnerable economy. We are reminded of the internationalist slogan of yesteryear: “Let Nicaragua Live.”

Yorlis Gabriela Luna is a grassroots educator and researcher in Boaco, Chontales, Zelaya, Central, Río San Juan, and Matagalpa, Nicaragua. Email: yorlisln@gmail.com.

An earlier version of this article was published in Spanish in Tensoes Mundiais

Translation from Spanish into English by Jill Clark-Gollub

References

ACOSTA, I. Informe de Gestión 2018: daños económicos a la economía nacional. Managua: Asamblea Nacional, 2019.

BLUM, W. Asesinando la esperanza: intervenciones de la CIA y del ejército de los Estados Unidos desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente, 2005.

BLUMENTAL, Max. US Gov. Meddling Machine Boasts off Laying the Groundwork for Insurrección in Nicaragua. The Grayzone, June 2018. Available from: https://thegrayzone.com/2018/06/19/ned-nicaragua-protests-us-government/ cited: 22 April 2019

BLUMENTHAL, M.; MCCUNE, N. How Nicaragua defeated a right wing US backed coup. In: AGJ – Alliance For Global Justice. Live From Nicaragua: Uprising or coup? [s.l.]: [s.n.], 2019. p. 60 – 77.

CENIDH – Centro Nicaraguense de los Derechos Humanos. Derechos humanos en un “estado de excepción”. Managua: CENIDH, 2019

CES – Consejo de la Economía Social. ¿Quién produce la riqueza en Nicaragua? Managua: CES, 2018.

DOSPITAL, M. Siempre más allá. Managua: Anamá Ediciones, 2013.

FONSECA TERÁN, C. ¿Quieren hacer una revolución? América Latina en Movimiento, Managua, 4 Jul 2018. Available from: https://www.alainet.org/es/articulo/193898 Cited: 2 Apr 2019.

SHARP, G. From Dictatorship to Democracy. Boston: The Albert Einstein Institute.1993

HENDRIX, E. El monopolio de la muerte o de como inflar una lista de muertos contra un gobierno. América Latina en Movimiento, Managua, 2018. Available from: https://www.alainet.org/es/articulo/194044 Cited: 10 Jan 2018.

KAUFFMAN, C. Introducción. In: AGJ – Alliance For Global Justice. Live From Nicaragua: Uprising or coup? [s.l.]: [s.n.], 2019. p. 10 – 13.

MACANO, B. Las configuraciones de los territorios rurales en el siglo XXI. Brasilia: Javeriana, 2009.

NUÑEZ, O. La Revolución Roja y Negra. Managua: Fondo Cultural Darío y Sandino, 2014.

______. Sandinismo y Socialismo. Managua: Fondo Cultural Darío y Sandino, 2015.

RAMIREZ, S. Introducción. In: Ramírez, S. (ed.). Pensamiento Político de Sandino. Barcelona: Biblioteca Ayacucho, 1988. p. 6-30.

SANTOS, B. de S. El Foro Social Mundial y la izquierda mundial. In: ALVARES, S. et al. Repensar la política desde América Latina: cultura, Estado y movimientos sociales. Lima: UNMSM, 2009. p. 365 – 409.

TRUCCHI, G. Nicaragua: Cuando las mentiras ganan y se convierten en realidad. Tercera Información, [online], 06 May. 2018 Available from: https://www.tercerainformacion.es/articulo/internacional/2018/06/05/nicaragua-cuando-las-mentiras-ganan-y-se-convierten-en-realidad-aceptada Cited: 1 Mar 2019.

VALENZUELA, R. ¿Porque las armas?: de los mayas a la insurgencia. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2009.

WADDELL, B. Laying the groundwork for insurrection: A closer look at the U.S role in Nicaragua´s social unrest. The Global Americans, Managua, 1 May 2018. Available from: https://theglobalamericans.org/2018/05/laying-groundwork-insurrection-closer-look-u-s-role-nicaraguas-social-unrest/ Cited: 20 Apr 2019.

WILLSON, B.; MCCUNE, N. US imperialism and Nicaragua. In: AGJ – Alliance For Global Justice. Live From Nicaragua: Uprising or coup? [s.l.]: [s.n.], 2019. p. 14 – 38.

ZEESE, K.; MCCUNE, N. Correcting the Record: What is Really Happening in Nicaragua? Popular Resistance, Managua, 10 Jul 2018. Available from: https://popularresistance.org/correcting-the-record-what-is-really-happening-in-nicaragua/. Cited: 5 Jan 2019.

—————————-

End Notes

[1] Translator’s note: WhatsApp is an instant messaging and VOIP platform widely used in Nicaragua.

[2] Translator’s Note: the opposition

[3] The dominance of the pro-coup version lasted about two weeks, and then transformed into anti-sandinista hate through postings on Facebook. At that point, people began responding and questioning this version. Young people began producing videos that showed how other videos had faked evidence; young Sandinistas carried out interviews with people who had supposedly been killed by the police, or with people who lived in towns that allegedly had been bombed by government forces. A whole new form of investigative journalism emerged.