The End of an Era: The Sun Sets on Mexico’s Pemex

By: Kelly Morrison, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

In July, the Mexican Congress is set to pass secondary legislation to further transform Mexico’s energy division.[1] For the first time in the 76 years since President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized the industry, the private sector will be able to share in the wealth of Mexico’s oil.[2] Though the international community is eagerly awaiting the chance to partake in the riches of Mexican oil, the domestic community is more skeptical of the pending changes. The Mexican Constitution guarantees state control over Mexico’s natural resources, and profits from state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) make up a third of the country’s tax revenues.[3] Therefore, the country’s oil has special significance for most Mexicans. To many, control of this vital natural resource is equated with national sovereignty and the self-sufficiency of the Mexican state. Accordingly, it seems that the country’s energy policy may prove to be the most contentious of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s reform initiatives.[4]

The proposal to allow the private sector to invest in Mexico’s oil industry will have significant social, economic, and political ramifications.[5] Private influence in Mexico’s most treasured national industry will have consequences for Mexican citizens’ social and cultural identity. The reforms will also impact domestic and international energy security.[6] Finally, the reform package has caused discord among Mexico’s three major political parties and will affect their prospects in future elections. This article will assess the diverse consequences of energy reform for the Mexican state and its people. With a history of corruption and inefficiency, no one can deny that Pemex is in need of reform. However, one must consider the negative externalities of Peña Nieto’s proposal before deciding whether this reform package is the best option for Mexico.

The Details

Last summer, Peña Nieto re-opened debate on the country’s oil and gas sector by introducing his reform proposals to the public. By December 20, both houses of the Mexican Congress and a majority of the Mexican states had passed constitutional amendments to allow for some private investment in the oil industry. The legislation revised Articles 25, 27, and 28 of the Mexican Constitution and added 21 transitional articles to institutionalize the changes. Previously, Pemex was a public entity akin to a department in the national government. With the reforms, however, Pemex became a “productive state enterprise.” Thus, foreign and domestic private companies, as well as other state-owned oil enterprises, will now be able to share profits with Pemex.[7]

The constitutional changes did not alter ownership of oil and natural resources at the wellhead or in the subsoil. These resources still technically belong to the Mexican state and to its people. According to Brookings energy expert Diana Villiers Negroponte, however, the constitutional reforms allow the Mexican Secretary of Energy (SENER) to “grant licenses to private institutions […] for all downstream activities, i.e. refining, pipelines, petrochemicals, transport, and even management of gas stations.” The National Commission of Hydrocarbons (CNH) will manage contracts for these endeavors, though Pemex will keep priority in the first round of bidding for contracts (la ronda cero). Pemex will also be subjected to independent regulatory bodies.[8] This new regulatory structure is one of the most important aspects of the reforms, considering the fact that Pemex has been known to feed patronage and clientelistic systems.

Congress must now pass secondary legislation in order to implement the constitutional adjustments. The new measures will define the exact relationship between Pemex and the private sector. They will also clarify the framework established for regulatory bodies.[9] For this reason, domestic and international investors have kept an eye on the drama that is unfolding in the Mexican legislature. American oil companies like Exxon and Chevron have expressed interest in bidding on downstream activities.[10] Chinese firms and Brazilian oil industry Petrobras are also looking for opportunities to partner directly with Pemex.[11] SENER estimates that Mexican oil reserves, including untapped resources, totaled 44,530 million barrels as of 2013.[12] Furthermore, as the world’s ninth largest oil producer, Mexico is a prime country for investment.[13] It makes sense why the private sector is eager to invest in Mexican oil.

Not Privatization

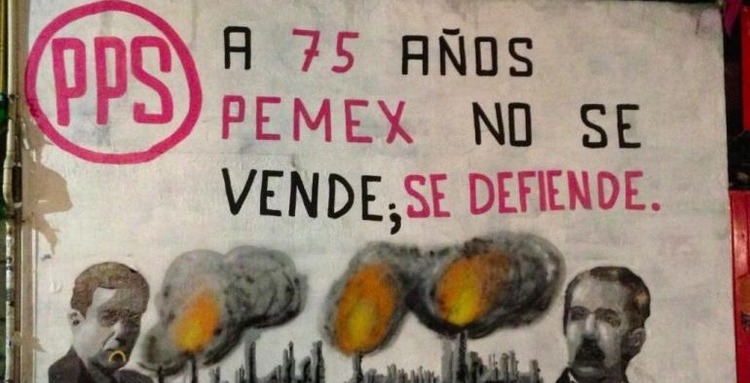

State control of the oil industry is a key part of Mexico’s national identity. Each year Mexicans celebrate Oil Expropriation Day with speeches and parades, honoring former president Lázaro Cárdenas for fighting to nationalize the industry.[14] Indeed, Pemex profits have given Mexicans a lot for which to be thankful. According to Jesús Zembrano Grijalva, president of the center-left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), Pemex has funded important welfare and national advancement projects that have bettered the lives of many Mexicans.[15] The revenue stream from Pemex explains why so many Mexicans have had such visceral reactions to the prospect of private interference in the energy sector. While many Mexicans do believe that Pemex should be reformed, about half of those polled last summer were found to be against the private sector’s involvement with the company.[16] Without a nationalized oil industry, many Mexicans wonder how the government will maintain sufficient tax revenues to fund its programs.[17

Members of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) argue that Pemex will be more efficient when it partners with international corporations, since Pemex does not have the technology it needs to extract oil from the deep waters of the Gulf. Those pushing for reforms note that Pemex possesses neither the technical sophistication, nor the capital necessary to exploit Mexico’s untapped resources.[18] Nevertheless, there is no guarantee that public-private partnerships will be advantageous for all of the parties involved. Nor is there an assurance that private industries will share their technology with Pemex and Mexican companies. Although general production may increase as a result of the reforms, one cannot be certain that Mexicans will directly benefit from these changes. Without efficient regulatory agencies, profits from the oil industry may simply flow into the pockets of foreign investors.[19] Ultimately, the PRD puts forth the most coherent counter-argument to the reforms: Mexico needs more comprehensive reform and efficient regulation if its oil industry is going to improve. The current package is simply insufficient to achieve these real changes.

For these reasons, Mexicans are rightly concerned with the sovereignty of their national oil industry. Aside from having an effect on tax revenue, the reforms will likely affect the 153,000 average citizens who work for Pemex. Recently, Peña Nieto promised that these employees would keep their jobs following the reforms.[20] However, one cannot be certain how foreign influence will impact the company’s workers, its management, and Mexico’s social sphere in general.[21] Given the social ramifications of these landmark changes, the Mexican government has struggled to convince its population that the pending reforms are in their best interest. As part of the effort to sell the reform package to the public, the government has spent 105 million pesos (more than $8 million USD) on a campaign that calls for citizens to say “no a la privatización: y si a la reforma energética” (“no to privatization, and yes to energy reform”). However, according to Justine Dupuy, a researcher with a Mexican research and analysis center, the public campaigns are merely propaganda. She fears that without constructive debate over the issue, the process towards energy reform will fall short of being entirely democratic.[22] Given the rushed nature of the reform process, and the lack of consultation with the Mexican people, the PRD argues that her qualms have merit.

Energy Reform: Donde el Pacto por México se Rompe

In spite of the societal implications of the new energy policies, Pemex is definitely in need of change. In fact, this is one of the main reasons why Mexico’s PRD stands against the current legislation. In a discussion at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington D.C. this March, party president Zembrano Grijalva explained his main concerns relating to the reform bill. He argued that the regulatory agency tasked with monitoring the oil industry would be unable to successfully regulate Pemex.[23] Rather than selling off aspects of the oil industry to the private sector, he proposed that effective reform and regulation of Pemex itself could increase the company’s efficiency. By reworking the company, production would improve and the oil industry would stay in the hands of Mexican citizens.[24]

Moreover, the PRD is worried about the individuals who would be impacted when the private sector begins working on public lands. The leftist party recognizes the environmental consequences that the reforms might bring and believes that the reform legislation should include environmental protection provisions.[25] Furthermore, the PRD is also concerned with the process of the reforms. Since, Peña Nieto rushed the legislation through Congress, the PRD feels that Congress shirked its responsibility to listen to the Mexican people. Thus, the PRD has proposed a consulta nacional(referendum) to give the Mexican people a voice in the reform process. Mexico will likely place a clause to overturn the legislation on the ballot during next year’s mid-term elections.[26]

The PRD is not the only party that wants to adjust the secondary legislation. Though the center-right National Action Party(PAN) has been an ally of the PRI during the reform process, the party has proposed adjustments to the current legislation. According to TheWall Street Journal, PAN senator Jorge Luis Lavalle estimates that 10 percent of the bill needs to be altered.[27] The party wants to ensure that the Senate can approve nominations to Pemex’s independent advisory board instead of giving the presidency carte blanche to make appointments. The PAN also wants to make sure that those who lose their land to the private sector be compensated.[28]

All in all, energy reform has been the most controversial of Peña Nieto’s initiatives. Though the PRI, the PAN, and the PRD were united in Pacto por México(Pact for Mexico) in 2012 to pass reforms in the education, telecommunications, and finance sectors,[29] Zembrano has declared that energy reform is where el pacto se rompe(the pact breaks).[30]

Looking Forward

The Mexican oil industry is certainly in need of reform. However, the PRD is correct in asserting that effective regulation for the oil sector is key. Additionally, that the government should consider the societal and environmental implications of their actions before moving forward.

As with any economic issue, Mexican energy reform is sure to result in winners and losers. The PRI has opted for what may be the most efficient option: allowing the private sector to invest in Pemex and the oil industry in general. However, the PRD seems to be more concerned with nationalistic interests. Given the pride and history associated with the oil industry, one must wonder how this dichotomy will impact future elections. If the PRD has correctly interpreted the wishes of the Mexican people, the party’s stance may increase its prospects of success in future elections. Zembrano hopes Mexican citizens will remember this moment when they take to the ballot box during the midterm elections next year. He also hopes that this issue will be a defining moment for the Mexican left. If this issue is as important as some surmise, perhaps a PRD candidate could take the presidency in 2018, for the first time in 60 years.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

References

[1]Francisco Reséndiz and Ana Anabitarte Enviado, “Peña, Reformas “A Más Tardar en Julio,” El Universal, June 10, 2014, accessed June 10, 2014, http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion-mexico/2014/penia-reformas-34a-mas-tardar-34-en-julio-1016033.html

[2] George Philip, “The Political Constraints on Economic Policy is Post-1982 Mexico: The Case of Pemex,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 18, no. 1 (1999): 35-50

[3] David Alire Garcia, “Mexico to Keep Pumping Pemex for Money Despite Promised Reforms,” Reuters, October 30, 2013, accessed June 8, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/10/30/mexico-reforms-pemex-idUSL1N0IB0OI20131030

[4] “Pact for Progress: A Conversation With Enrique Peña Nieto,” Foreign Affairs (January 2014): 4-10

[5] Andrew O’Reilly, “Mexico’s Peña Nieto Pushes Oil Reform Despite Strong Opposition, FoxNews Latino, August 7, 2013, accessed June 4, 2014, http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/money/2013/08/07/mexico-pena-nieto-pushes-oil-reform-despite-strong-opposition/

[6] “Giving it Both Barrels,” The Economist, August 17, 2013, accessed June 4, 2014, http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21583664-government-has-made-promising-start-it-may-struggle-bring-historic-reform?zid=305&ah=417bd5664dc76da5d98af4f7a640fd8a

[7] “The Future of Energy Reform in Mexico,” Discussion from Brookings, Washington D.C., January 16, 2014, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/events/2014/1/16%20energy%20reform%20mexico/energy%20reform%20mexico%20uncorrected%20transcript.pdf

[8] Diana Villiers Negroponte, “Mexican Energy Reform: Opportunities for Historic Change,” Brookings, December 23, 2013, accessed June 4, 2014, http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2013/12/23-mexican-energy-reform-opportunities-historic-change-negroponte

[9] Noe Torres, “Mexico Senate Pushes Back Talks on Key Energy Reform Legislation,” Reuters, June 5, 2014, accessed June 8, 2014, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/06/05/uk-mexico-energy-reforms-idUKKBN0EG0AK20140605

[10] Gregg Laskoski, “The Promise of Mexican Oil,” US News, June 4, 2014, accessed June 9, 2014, http://www.usnews.com/opinion/economic-intelligence/2014/06/04/why-us-oil-companies-want-to-partner-with-mexicos-Pemex

[11] Adam Williams, “Pemex in Talks for $4 Billion Investment Fund With China,” May 28, 2014, accessed June 4, 2014, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-05-28/Pemex-creates-4-billion-investment-fund-with-china.html

[12] “Secretaría de Energía,” http://sie.energia.gob.mx/bdiController.do?action=cuadro&cvecua=AC04

[13] “U.S. Energy Information Administration,” http://www.eia.gov/countries/

[14] Randal C. Archibold and Elisabeth Malkin, “Mexico’s Pride, Oil, May be Opened to Outsiders,” The New York Times, December 12, 2013, accessed June 8, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/13/world/americas/mexico-oil.html?_r=0

[15]Jesús Zembrano Grijalva, “Mexico’s Energy Reforms: The View From the Left,” Discussion from The Wilson Center, Washington, D.C., May 28, 2014

[16] Miguel Ángel Vargas V., “5 Encuestas Sobre la Reforma Energética y el Capital Privado,” ADN Político, August 20, 2013, accessed June 10, 2014, http://www.adnpolitico.com/gobierno/2013/08/20/5-encuestas-sobre-la-reforma-energetica-y-el-capital-privado

[17] Jesús Zembrano Grijalva, “Mexico’s Energy Reforms: The View From the Left,” Discussion from The Wilson Center, Washington, D.C., May 28, 2014

[18] Sonia Corona, “Las Nuevas Reglas de la Reforma Energética de México,” El País, May 2, 2014, accessed June 8, 2014, http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2014/05/02/actualidad/1399043286_447835.html

[19] Laura Carlsen, “Mexico’s Oil Privatization: Risky Business,” Foreign Policy in Focus, May 27, 2014, accessed June 4, 2014, http://fpif.org/mexicos-oil-privatization-risky-business/

[20] Adam Williams, “Pemex, Mexico’s State Oil Giant, Braces for the Country’s New Energy Landscape,” The Washington Post, June 6, 2014, accessed June 8, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/pemex-mexicos-state-oil-giant-braces-for-a-the-countrys-new-energy-landscape/2014/06/04/07d171d6-ea69-11e3-93d2-edd4be1f5d9e_story.html

[21]Alma E. Muñoz, “Aprobación de Leyes Energéticas, Grave Riesgo para el País: Cárdenas,” La Jornada, June 10, 2014, accessed June 10, 2014, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/ultimas/2014/06/10/aprobacion-de-leyes-energeticas-grave-riesgo-para-el-pais-prd-6523.html

[22] Rafael Cabrera, “Infografía: ¿Cuánto ha Costado Promover las Reformas de Peña Nieto?, Animal Político, November 19, 2013, accessed June 4, 2014, http://www.animalpolitico.com/2013/11/cuanto-ha-costado-promover-las-reformas-de-pena-nieto/#

[23] Shannon Young, “American Media Misses the Story on Mexican Oil Reform,” Texas Observer, February 10, 2014, accessed June 9, 2014, http://www.texasobserver.org/american-media-misses-story-mexican-oil-reform/

[24] Jair López and Édgar Amigón, “PRD Presenta su Propuesta de Reforma Energética,” El Financiero, February 7, 2014, accessed June 11, 2014, http://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/archivo/prd-presenta-su-propuesta-de-reforma-energetica.html

[25] Laura Carlsen, “Mexico’s Oil Privatization: Risky Business,” Foreign Policy in Focus, May 27, 2014, accessed June 4, 2014, http://fpif.org/mexicos-oil-privatization-risky-business/

[26] Miguel Ángel Vargas V., “Consulta Popular, el ‘Talón de Aquiles’ de la Reforma Energética: Zembrano,” CNN México, March 18, 2014, accessed June 11, 2014, http://mexico.cnn.com/nacional/2014/03/18/consulta-popular-el-talon-de-aquiles-de-la-reforma-energetica-zambrano

[27] Juan Montes, “Mexican Conservatives Seek Adjustments in Energy Bill,” The Wall Street Journal, May 28, 2014, accessed June 4, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20140528-710561.html

[28] Alberto Morales and Juan Arvizu, “Busca PAN Siete Modificaciones a Reforma Energética,” El Universal, June 10, 2014, accessed June 11, 2014, http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion-mexico/2014/pan-modificaciones-reforma-energetica-siete-1016183.html

[29] “Pacto Por México,” http://pactopormexico.org

[30] Luis Pablo Beauregard, “El PRI y el PAN Traicionaron su Propia Firma,” El País, December 22, 2013, accessed June 11, 2014, http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2013/12/22/actualidad/1387679173_626206.html