The Cuban Five for Alan Gross: A Swap That May Make Preeminent Sense

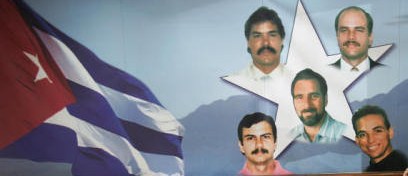

Thirteen years after their imprisonment, the ill-fated Cuban Five have been looked upon, depending on one’s perspective, as either tragic figures or infamous conspirators. Consisting of five Cuban intelligence officers, the detainees were convicted in 1998 of spying on U.S. military installations, a charge vehemently denied by Havana, which claimed that their role was to monitor Miami-based “terrorist” exile groups that were regularly plotting and carrying out attacks against their homeland. On October 7, 2011, one of the Five, René González, was released from federal prison after serving his sentence. However, according to the terms of his release, one could argue that only the nature of his confinement has changed. González, who has dual U.S.-Cuban citizenship, will be forced to serve three years under supervision in the U.S. This could expose him to threats from extremist exile terrorists based in Florida, undoubtedly adding to the misery weighing on González and his family. Since her husband’s detainment, González’s wife has not even been allowed entry into the U.S., still another disturbing aspect of the Obama administration’s already crumbling Cuba policy.

The failure to take the positive step of allowing González and the remaining members of the Cuban Five to return to the island has been met with outrage as well as storms of criticism back in Cuba on all levels of Cuban popular opinion. Campaigning on the grounds of humanitarianism and fundamental social justice, scores of groups including the African National Congress, the Cuban Parliament, as well as the International Committee for the Freedom of the Cuban Five, have urged President Obama to grant the unconditional release of the Cuban intelligence officials.

While González is the first of the Cuban Five to be released, the main question that remains then is how the would-be ‘carrot’ that has now been dangled before the Castro administration can be made to influence the status of Alan Gross, a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) contractor imprisoned for alleged espionage activities in 2009, who the White House would love to see released. Since González was released from detention, the president of the Cuban Parliament Ricardo Alarcón has dismissed the notion of a unilateral gesture that would bring about the early release of Alan Gross. In a stinging attack, Alarcón described former UN Ambassador Bill Richardson’s diplomacy as “amateur,” adding that he has “entangled everything” by suggesting a direct swap of González, who was close to finishing his sentence, with Alan Gross, who has only begun his.

Judging by the failed, but not necessarily useless humanitarian visits to Cuba by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Richardson, the point is being driven home to President Obama that he will have to make substantive rather than illusionary concessions to mend frayed U.S.-Cuban relations. The release of René González could be a constructive bilateral gesture, though its impact has now been somewhat mitigated by the spat surrounding its conditions. At the same time, Obama might respond to global voices calling for the release of the jailed Cubans and use his constitutional powers to offer executive clemency to the Five as part of a deal for Alan Gross’ release.

Both countries seem stuck in a fallow Cold-War scenario, reluctant to lose what could prove to be only pseudo leverage over one another. If Obama wants to stay true to his words relating to his vision of a new beginning with Cuba, he might start by eliminating useless bromides from his rhetoric and offer a serious deal to Havana that would provide a self-respecting government grounds for acceptance.

This analysis was prepared by COHA Research Associate Faizaan Sami.