The Asháninka: Illegal logging threatening Indigenous Rights and Sustainable Development in the Peruvian Amazon

By: Mariana Araujo Herrera, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

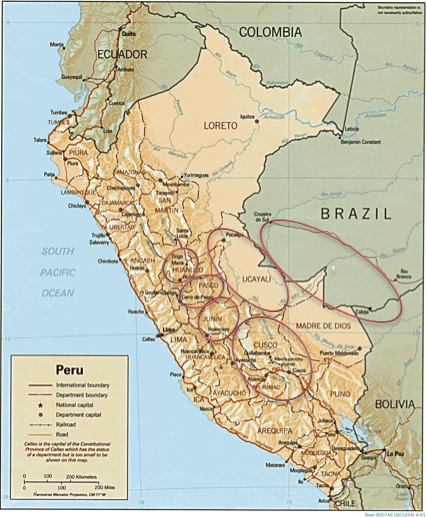

September marks one-year since the murder of Edwin Chota and three other Asháninka natives by a group of illegal loggers. On September 1, 2014 Chota and three other members from his community were traveling to the border of Brazil to join up with Asháninka villagers to discuss the growing problems caused by the illegal timber industry. Shortly before they were able to meet with the neighboring village, they were intercepted by a group of illegal loggers and shot to death. Edwin Chota was the leader of the Asháninka community in Saweto Ucayali and an outspoken advocate for indigenous rights, in which his primary focus was to put an end to the illegal logging industry. Between 2002 and his untimely death, Chota strongly advocated for a peaceful and sustainable community in the Peruvian Amazon. He relentlessly fought the illegal timber industry in order to prevent the destruction of the indigenous Peruvian homeland, asking the Peruvian authorities for recognition of the titles of native properties. Today, out of the 250 thousand acres of land and 243 communities in the region, 212 have been given the titles to their land.[1]

Illegal logging in Peru became prominent in the 1970s in the highlands of Ucayali and Bajo Urubamba. Since then it has spread all throughout the Peruvian Amazon. The practice of illegal logging normally deeply affects the Amazon and is detrimental to the communities in the region. The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Ucayali and Loreto found that between 78 and 88 percent of the timber extraction in the area is done without proper certification.[2] In 2002, INRENA reported to the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) that about 500,000 cubic meters, 40 percent of the national product of timber, is extracted illegally.[3]

The timber extraction business is highly lucrative. There is a high demand for paper, paper packaging, and extract of timber products. The industry enjoys a high profit margin. According to the World Bank, the illegal logging industry realizes some $10 billion in revenue annually.[4] Just as the profits are high, so is the level of environmental destruction. The damage being done is almost irreparable, creating devastating deforestation, loss of biodiversity, risk of animal extinction, and increasing problems related to climate change. The industry triggers a chain of events resulting in a sequence of human rights abuses and violence amongst indigenous communities, including the Asháninkas.

The Asháninka community is one of the largest indigenous groups to be found in South America, with a population estimated up to 70,000 people.[5] The Asháninka’s homelands stretch from the state of Acre Brazil to the Amazon rainforests in Peru.[6] While the various communities in this region are located in geographically distinct communities, the Asháninkas are all united through the same lifestyle, language, and beliefs. They maintain very close ties with their neighboring communities, often traveling by boat to pay each other visits and provide support in times of difficulty. The Asháninkas have a variety of cultural beliefs that enrich the country. The community of Edwin Chota is located in Saweto Ucayali, close to Peru’s border with Brazil.

The Asháninkas maintain a subsistence lifestyle and as such are inextricably connected to the land on which they live. They use the land for housing, agriculture, hunting, and fishing.[7] Within the communities, responsibilities are divided based on genders. Men are in charge of hunting, which also consists of tapir, boar and monkeys, and women maintain gardens of fruits and vegetables, contributing to a large portion of their nutrition. The Asháninka often paint their faces; it is a tradition they use to exteriorize their feelings and moods. They use the seeds from the achiote trees, which provides them a pigment known as urucum. This pigment has now become one of the world’s most important natural food colorants.

The Asháninka people hold a strong spiritual connection with the land. As a community that works together to take care of the rainforest, they periodically migrate to a different location in order to let the land regenerate.[8] This migration exemplifies their dedication to protecting the land and maintaining a sustainable environment that they can return to. Unfortunately, illegal logging in the areas of the Asháninka communities has had a devastating impact on their lifestyle.

The ongoing dispute between illegal loggers and the Asháninka communities, however, is not the first instance in which the livelihood of the Asháninkas has been under threat. During the 1980’s and 1990’s the terrorist group Shining Path and the counter-insurgency forces threatened the Asháninka, several communities disappeared all together.[9] Foreign companies have also invaded the region to engage in rubber tapping and cultivating coffee plantations. In 2010 the Brazilian and Peruvian governments allowed Brazilian companies to build large dams,[10] leading to further displacement for the Asháninka. Survival International, an international non-governmental organization, is pushing the Brazilian and Peruvian governments to protect the homelands of the Asháninka in the region. COHA stands with Survival International on their efforts to protect the rights and defend the lifestyle of this indigenous group. However, a larger response is needed from the international community—especially from organizations that focus on aiding minority groups.

Since the death of Edwin Chota, the government of Peru has finally started to take action. Ana Jara, the former President of the Council of Ministers (PCM), travelled to Saweto 19 days after the murder of Edwin Chota to deliver medicine and social aid for the Asháninka community. Jara also announced the creation of a High Commissioner for the Fight Against Illegal Logging.[11] While it is reassuring to see the government of Peru take these modest actions in support of the Asháninka communities, these actions from the government should have commenced some 10 years ago when Chota first began advocating for sustainable development and indigenous rights in his community. Moreover, there still remains myriad of issues that the Peruvian government must address. These include: increasing property rights, access to education and healthcare, as well as security for minority groups. It is completely unacceptable that a tragedy must occur in order for the government to take action.

After Chota’s death, his community continued to demand property rights to the 80,000 acres that Saweto thinks belong to their community. The Regional Government of Ucayali gave the Saweto Asháninka community the rights to 78,611 acres on January of 2015.[12] Despite this action, the Asháninka continued to express to the Peruvian government their feelings of abandonment and marginalization for not showing involvement in protecting their communities. In line with this was the mismanaging of the investigation of Chota. The main newspaper in Peru, El Comercio, reported that the investigation from the district attorney’s office of the province of Ucayali was stalled and took up to 11 days to find only the first body.[13] Blood samples were taken to Lima to confirm the victims’ identities, which also slowed down the process of finding justice for the families of those murdered.

One year after Edwin Chota’s death, the battle with the illegal loggers still drags on. Even after Asháninka communities were presented with land titles. The government has yet to respond to the requests of the Asháninka for access to health and education. The visit of Ana Jara or any other political power figure to Saweto are not enough, since the involvement should be constant and not only when breaking news put this community in the spotlight.

Poverty for disadvantaged communities is a common theme throughout Latin America. This ends up not only harming minority groups, but also the country as whole. It is time to take action on these issues and treat these indigenous communities as citizens, not outsiders. Edwin Chota’s efforts to protect these communities should not die with him. The United States and the European Union, whom are the main importers of Peru’s timber products, could also play a vital part by creating bans against the illegal timber trafficking.

Most illegal loggers are locals who find themselves with a lack of alternate economic resources that would enable them to provide for their families. Out of desperation, this causes many to take the jobs available in the illegal logging trade without considering the detrimental environmental, social, and economical consequences. This, however, is no excuse for the tremendous damage being caused in the region at all levels. President Ollanta Humala has failed to equalize the expenditures for all regions and has not carried out the promises to reduce poverty that he made during his campaign. The Asháninka are vibrant, intelligent communities that advance sustainable development in the Amazon through their lifestyle and enrich the cultural diversity of the country. Peru must protect these people of the Amazon, and in so doing, protect the pachamama, mother earth.

By: Mariana Araujo Herrera, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured Photo: Indígenas Ashaninka Aldeia Apiwtxa (Pedro França/MinC)

[1] Diario El Comercio. “A Un Año De La Muerte De Edwin Chota: Bosques Siguen Sin Dueño.” Elcomercio.pe. El Comercio, 10 Sept. 2015. Web. 11 Sept. 2015. http://elcomercio.pe/peru/ucayali/ano-muerte-edwin-chota-bosques-siguen-sin-dueno-noticia-1839796

[2] MARONI Consultures SAC. “Análisis Preliminar Sobre Gobernabilidad Y Cumplimiento De La Legislación Del Sector Forestal En El Perú.” Sociedad Peruana De Ecodesarrollo. October 1, 2006. Accessed September 18, 2015. http://www.spde.org/documentos/publicaciones/tala-ilegal/CAP-V.pdf

[3] Ibid

[4] Greenpeace International. “Illegal Logging.” Greenpeace International. January 30, 2008. Accessed September 22, 2015. http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/forests/threats/illegal-logging/

[5] Survival International. “The Asháninka: The Asháninka of Acre State, Brazil, Have Recently Reported Encountering Dozens of Uncontacted Indians Close to Their Community in Simpatia Village.” Survival International. Survival International, n.d. Web. 14 Sept. 2015. http://www.survivalinternational.org/galleries/ashaninka

[6] “Edwin Chota.” Rainforest Foundation US. Rainforest Foundation US, n.d. Web. 12 Sept. 2015. http://www.rainforestfoundation.org/edwin-chota

[7] Survival International

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Diario El Comercio. “Ana Jara Se Dirige a La Comunidad De Saweto.” El Comercio, September 20, 2014. Accessed September 17, 2015. http://elcomercio.pe/peru/ucayali/ana-jara-se-dirige-comunidad-saweto-noticia-1758387

[12] Diario El Comerico. “Ucayali: Excluyen a Saweto De Bosques Para Producción Maderera.” El Comercio, April 6, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2015. http://elcomercio.pe/peru/ucayali/ucayali-excluyen-saweto-bosques-produccion-maderera-noticia-1802436

[13] Diario EL Comercio. “Encuentran Los Restos Del Tercer Asháninka Asesinado En Ucayali.” El Comercio, September 19, 2014. Accessed September 20, 2015. http://elcomercio.pe/peru/ucayali/ashaninkas-ucayali-edwin-chota-encuentran-restos-tercer-ashaninka-asesinado-noticia-1758061?ref=nota_peru&ft=contenido