El Salvador: The Truth Commission and the Jesuit Massacre

- Twenty Salvadoran soldiers await trial in Spain for crimes against humanity perpetrated during the Salvadoran Civil War.

- The extradition of war criminals to be tried under the Spanish judicial system draws attention to profound weaknesses in Salvadoran trial.

- A growing number of Salvadorans are beginning to show unease that the nation’s moderate President Mauricio Funes will move the country beyond the social causes of conflict in the 1980s.

Crime without Punishment

The outbreak of the Salvadoran Civil War in 1980 initiated twelve years of violent conflict within Central America’s most densely populated nation. For years, President Ronald Reagan employed a traditional Cold War platform to reinforce conservative governments, insisting that the leftist insurgency organization, the Frente Faribundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), posed a dangerous threat to global democracy. The Jesuit massacre in 1989 forced the international community to recognize the horrendous scores of crimes against humanity that transpired throughout the Salvadoran Civil War. In 1991, the Salvadoran courts finally convicted twenty members of the military of war crimes; but this relatively small step towards justice rang hollow when all twenty soldiers were released only two years later under the terms of an international amnesty law.[1] Spanish Judge Eloy Velasco recently reopened the case under the universal jurisdiction law, expressing his personal objection regarding the failure to bring the militants and associated death squads to justice.[2] While the resurrection of the case may represent a small triumph for civic rectitude and the eight victims of the Jesuit Massacre, it is quite possible that the culprits would once again escape conviction, as few precedents are in place regarding universal jurisdiction law.[3]

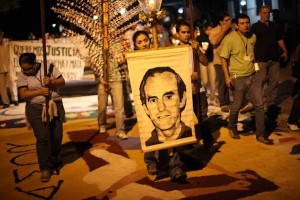

The Jesuit Massacre

On November 16, 1989, twenty Salvadoran soldiers murdered six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter. The Jesuits had a long-standing affiliation with liberation theology, and government officials suspected the priests of sympathizing with the FMLN insurgency. The six priests had advocated peaceful negotiation between the rebels and the government, and Judge Velasco has since held that the Jesuits’ promotion of peaceful negotiation between the rebels and the government was likely “the fundamental motive for the killing.”[4] The slain priests were affiliates of the prominent University of Central America (UCA) and were major contributors to Salvadoran intellectual life. The brutal execution of these unarmed men and women elicited public outrage while providing the impetus for the inevitable intervention of international and regional peacekeeping organizations.[5] The United Nations helped broker the Chapultepec Peace Accords of 1992, ordering an immediate cease-fire and the implementation of social, political, and economic reforms.

To guarantee the successful enactment of the Accords, the UN established the Truth Commission and the Ad Hoc Commission to “investigate past human rights abuses and propose corrective measures to prevent future abuses.”[6] The Truth Commission eventually found former Defense Minister and Colonel René Emilio Ponce responsible for mandating the execution of the priests.[7] Another former minister of defense, General Rafael Humberto Larios, and eighteen other soldiers were indicted in Spain on charges of crimes against humanity and terrorist killings.

The Case

On May 31, 2011, Judge Velasco distributed international warrants to the Spanish police and Interpol demanding that the defendants be present for trial within ten days of issuance.[8] The Spanish judge claimed jurisdiction over the case based on a preexisting extradition treaty with El Salvador and allegations of foul play in the original trial proceedings.[9] Velasco expressed his disdain for the farcical trial previously held in El Salvador, asserting that the “judicial process was a defective and widely criticized process that ended with two forced convictions and acquittals even of confessed killers.”[10] The case’s outcome is yet to be determined, but it is clear that Spanish officials have a vested interest in the conviction and incarceration of the perpetrators, as five of the six Jesuits killed in the 1989 massacre were of Spanish birth.[11]

The Legacy

January 16, 2012, will mark the twentieth anniversary of the Chapultepec Peace Accords, but painfully limited progress has been achieved since the treaty’s symbolic ratification. The bloody civil war resulted in some 75,000 casualties, 85 percent of which were supposedly perpetrated by soldiers, security forces, and death squads.[12] While the Truth Commission’s investigation into the perpetrators of war crimes is certainly a step towards justice, the flawed prosecution of the men responsible for the Jesuit massacre reveals the prolonged ramifications of the war. In spite of the symbolic success of the Chapultepec Accords, El Salvador still struggles to eradicate the social injustices that spurred the outbreak of the ghastly conflict and the continued appalling procedures it witnessed.

The 2009 election of FMLN President Mauricio Funes put an end to two decades of conservative rule in El Salvador. Throughout his campaign, Funes compared himself to U.S. President Barack Obama as a symbol of revolutionary social change.[13] In spite of the President’s initially fervent support, the Salvadoran people have grown critical of Funes and his administration’s general lack of progress, as well as his lack of political courage.[14] Since his election, Funes has made some effort to combat his nation’s characteristic impunity, placing a particular importance on the prosecution of human rights violations and venality.

Preliminary hearings opened on April 5th to investigate corruption charges against high-level officials of the previous ARENA administration; and the trial of a former Salvadoran general accused of war crimes and human rights violations, commenced in Orlando, Florida on April 18th.[15] These cases demonstrate the President’s aspiration to prosecute corrupt officials and war criminals within a reasonable time frame, in addition to his understanding of the nation’s severely flawed judicial system. The need to extradite cases to Spain and the U.S. is worrisome, as it could become increasingly difficult to combat impunity without a stable and effective judicial system in El Salvador. Regardless of the jurisdictional politics of the Jesuit massacre trial, Spain’s attention to the case represents an emblematic victory for the massacre’s victims.