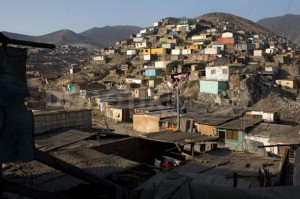

Some “Young Towns” in Lima Not So Young Anymore

Regardless of their name, shantytowns, slums, Villas Miseria, favelas, or Pueblos Jóvenes (young towns) as they are known in Peru — these settlements have been a ubiquitous presence in nearly all major Latin American cities for decades. They are seen by some as a cesspool of poverty, crime, and misery, a community resting precariously on the margins of society. However, significant advancements made recently in education, sanitation, and infrastructure in the Pueblos Jóvenes Slums of Lima, Peru suggest that these once disadvantaged, ostracized communities are now of a different complexion. Even amid widespread poverty, economic development has managed to creep its way into once squalid corners. Moreover, the shantytowns surrounding Lima encapsulate both Peru’s optimistic future and the long road that still remains ahead.

Lima’s Pueblos Jóvenes Continue to Struggle

Today, approximately 50% of Lima’s population lives in poverty, an ongoing challenge for planners and policy-makers. Yet, these informal settlements are more organized than in other cities. Unfortunately, many residents of Lima’s informal settlements feel forgotten or failed by the Peruvian government, and oftentimes with good reason. As Ian Vásquez of the Cato Institute states, “[P]eople in Lima’s squatter settlements rely on their wits to overcome any number of obstacles thrown up by government.” The low quality of public schools in these districts forces families to pay for private schools if they want their children to receive an adequate education. Meanwhile, the failure of SEDAPAL, Peru’s government organization responsible for water provision, to meet the water needs in these communities forces residents to purchase often unsanitary water from trucks that costs 10 to 15 times more than piped water would.

But, the Times They are A-Changing

Located in the Northern region of Lima’s metropolitan area, Los Olivos is one example of real change and concrete improvement in an area that began as a pueblo jóven decades ago. “No longer a slum, [Los Olivos] is a vast lower-middle-class suburb, boasting the MegaPlaza (billed as one of the largest shopping malls in South America), gated neighborhoods, mammoth casinos and plastic surgery clinics.” Despite the formalization and gentrification of one community, almost 50 percent of those falling within the middle-income brackets live in Lima’s Conos, in precarious settlements to the North, East, and South of Lima. Much of this population is largely of migrant origin and employed in the informal economy.

Even in more recently settled communities like Pachacútec, established only 11 years ago and roughly 30 miles from the city center, great improvements can be witnessed. This neighborhood, named after the triumphant founder of the Incan empire, today maintains paved roads, electricity and water; this development has been driven largely by Peruvian entrepreneurial spirit. Gastón Acurio, famed Peruvian chef, views culinary training as one means of escaping poverty. To this end, he has established the Pachacútec Culinary Institute which trains participants in culinary principles only after completing coursework in math, language, history and geography. Participants must complete several internships and take English classes. The goal of thisendeavor is to train new chefs in the rich Peruvian culinary tradition while simultaneously lifting participants out of poverty and equipping them with a marketable skill set.

Positive change is evident in the oldest settlements surrounding Lima, however with few exceptions those formed within the last 10 years still experience a large degree of isolation and suffer from extreme poverty. Worse yet, much of the solidarity among the poor populations of Lima present during the 1980s no longer exists. The oldest settlements – Comas, San Martín de Porres, Los Olivos, Independencia and San Juan de Miraflores – have reached a very high level of integration into Metropolitan Lima, as evidenced by a greater connection to the municipal water distribution network and an increasing level of economic and social inclusion. Middle-aged districts, those that emerged in the 1970s such as Villa El Salvador, see water connection rates of 50 to 79 percent, while more peripheral, recently settled areas see connection rates of 25 to 49 percent. In the youngest districts, most sparsely populated and furthest from the heart of the capital, less than 25 percent of homes have access to running potable water.

Looking toward the future

The signs of true change in Lima’s pueblos jóvenes represents both further growth and the progress yet to come. Largely due to the efforts of the settlements’ inhabitants themselves, with only limited and intermittent support from the government, life in many of Lima’s slums has improved greatly. Once haplessly built shantytowns have been transformed into vibrant communities. However, a significant amount of development remains incomplete and poverty still spreads throughout much of Lima’s population; many more pueblos jóvenes remain largely ignored.

Written by COHA Research Associate Daniel Whalen

This is the third issue in a series exploring the concept of the New Latin America by focusing on recent developments that highlight how the present region contrasts with its past.