Small Earthquake in Alberta

By: Nicholas Birns, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

One of the Western Hemisphere’s last single-party states finally gave way to an opposition government this week. And no, I am not speaking of Cuba, but of the Canadian province of Alberta, where the Conservative Party held sway for forty-four years, –a record rivaled in the hemisphere only by Mexico’s PRI hegemony from 1929 to 2000 and that of Paraguay’s Colorado party from 1947 to 2008. This development is not just of quaint or local interest, but could signify a tectonic generational and political shift against free-market conservatism and libertarianism, and towards a more populist and egalitarian agenda. It also has the potential to augur a federal Liberal or NDP victory in Canada this year, which would decisively alter the course of Canada’s energy, security, and diplomatic attitudes with respect to Latin America and the larger hemisphere.

Alberta has long been considered the Texas of Canada: oil-rich, pro-free-market, culturally conservative, and adamantly rejecting any form of government regulation or socialism. Whereas Republicans have only held control of Texas for a paltry twenty years, Alberta has been under Conservative sway for twice as long. In other Canadian provinces, parties alternated in a variety of configurations, right and left, and, in Québec, nationalist and federalist. But in Alberta it has been a continuous Conservative rule. An Albertan turning fifty this year would have remembered only a string of Tory premiers: relatively moderate Peter Lougheed, Don Getty, Ralph Klein, Ed Stelmach: all white males of affable demeanor, a light and selective comprehension of policy issues, and a hard-right approach to governance. The conservative patrimony was not only electoral but intellectual, as per the prestige and influence of the Calgary school of conservative academic political scientists—including Tom Flanagan, David Bercuson, Rainer Knopff, and Ted Morton, the last of which actually held office in the Stelmach government and ran for the party leadership himself. Indeed, recent attempts to dislodge the Tories from ruling in Edmonton were largely spearheaded from the right–the libertarian WIldrose Party, founded by Danielle Smith and now led by Brian Jean, promised Albertans less a radical shift in policy than a set of new faces. WIldrose was largely favored to win in 2012, but lost, as the Conservatives trumped the novelty of a female leader in Smith by installing a woman, Alison Redford, as the new Tory premier. The failure of the polls to predict the winner in this case, as well as the unexpected triumph of British Columbia Premier Christy Clark in 2013 when the polls had counted her out, led observers to be skeptical when, earlier this year, polls showed the Conservatives, now led by Redford’s hapless and overmatched successor, Jim Prentice, to be trailing not only Wildrose but the leftist New Democratic Party. The NDP had originated as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), founded in Calgary in 1932, and was associated with Prairie radicalism, routinely governing in Alberta’s fellow Prairie Provinces Saskatchewan and Manitoba, in the latter of which its embattled premier, Greg Selinger, is still in office. Alberta has been the incubator of many social movements, both right and left. But Alberta, so similar topographically and culturally to its neighbors, for the most part, has always been very different politically.

Thus the rise in the polls of the Alberta NDP and its leader, Rachel Notley, seemed an anomaly, and journalists and pundits confidently predicted that the actual tally would see the leftists fade and thee Conservatives comfortably back on top. But, instead, the results were directly in line with the polls. The prominent Canadian polling website ThreeHundredEight.com had projected the NDP to win 51 seats; they ended up winning 54. The Conservatives fell behind Wildrose, winning over ten seats to the upstart party’s 21.

Notley’s ascent to the Alberta premiership shows how stark the difference is between her generation and its predecessor, her father, Grant Notley, who died in a plane crash in 1984, was the NDP leader on the provincial level at the time of his death. Grant Notley was an admired man who built up the Alberta NDP considerably, but his quest for power turned out to be a quixotic one in a province whose center of political gravity was so far to the right. His daughter though, will lead a changed Alberta. Edmonton, the provincial capital, has always been politically liberal, but was continually outvoted by rural areas of the province as well as Alberta’s traditionally more conservative other major metropolis, Calgary, But Calgary has changed in recent years, having first elected and then reelected a popular, left-leaning, Tanzanian-born Muslim mayor, Naheed Nenshi, who has galvanized a pro-environment, pro-multicultural base in his city, earning the vituperative criticism of right-wing journalists such as Ezra Levant. With both major cities willing to consider more progressive policies, the rural base that had long been the conservatives’ anchor was free to actually consider alternatives and to buck the oil-driven hegemony that had never truly held a popular consensus in the province, even if dominating its political culture.

The British historian Sir Alistair Horne titled his 1972 book on the election of the Marxist Salvador Allende to the Chilean presidency in 1970 Small Earthquake in Chile. Though earthquakes are more rarely seen on the Canadian prairies than the Chilean cordillera, Alberta’s election of a progressive majority represents a major ground shift in Canadian policies, especially for Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who began his political career in Alberta, and is facing an election this year. Harper has enjoyed a nearly ten-year run in Ottawa, forming first a minority government and then building a majority at the expense of two hapless Liberal leaders, the earnest policy wonk Stéphane Dion and the overconfident public intellectual, Michael Ignatieff. Now, the Liberals have returned to the family of their greatest leader, as the young and highly talented Justin Trudeau, son of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau is neck and neck with Harper in the polls. Politics in Canada are complicated by the fact that the left-of-center electorate is divided between two parties the more moderate Liberals and the more radical NDP. As the Liberals have been largely based in Québec and Ontario, and the NDP on the prairies, the parties have only rarely cannibalized each other’s votes. But recent years have seen a federalization of Canadian politics, with the NDP garnering a substantial number of federal seats in Québec and the Liberals, as said before, holding power for quite some time in the previously NDP-leaning British Columbia. This might complicate the attempts of the Left to dislodge Harper, although a Liberal-NDP coalition is also plausible.

What is undoubted is that the Canada which has provided such succor to US conservatives with its support for war in Afghanistan and its construction of the Keystone Pipeline–is no longer quite so firmly in their camp. A new Canadian government, whether under the leadership of the energetic Trudeau or the more seasoned NDP federal leader Thomas Mulcair, would also change Harper’s policies towards Latin America, Whereas Canada had earlier been–before the 1960s, generally–uninterested in its southern hemispheric neighbors, and then, during the Trudeau era, espousing a generally progressive line in Latin America, with especial outreach to a Cuban government ostracized by the US, Harper’s Latin American policy has been aggressively conservative and free-market. Whereas Canada had once been the good cop to the US”s bad cop, showing respect and outreach towards leftist forces spurned by the US, the opposite has been true of late. Under Harper, the Canadian government has outdone the United States in its hostility towards the region’s dissident and populist forces. In his book, The Ugly Canadian: Stephen Harper’s Foreign Policy, Yves Engler noted Harper’s “hostility towards the leftward shift in Latin America, a number of criticisms of the Venezuelan government, and going out of its way to criticize the Venezuelan government.” Harper recognized the post-coup governments in Paraguay and Honduras while few other hemispheric powers did. Engler contends that the Canadian embassy in Caracas has ben a fount of criticism against the Venezuelan regime, openly criticizing then-Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez without maintaining any pretense of diplomatic neutrality. Though Harper has not carried matters to an extreme—he has not diminished the cordial and lucrative Canadian trade relationship with Cuba, perhaps in knowing anticipation of a US-Cuban rapprochement—his policy towards Latin America has centered around free trade and criticism of leftist regimes, with NAFTA and its laissez-faire implications as a sort of ideological cornerstone.

The web site of the Canadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs says that “Canada is a country of the Americas and, as such, we place great value in fostering lasting and meaningful relationships with countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.” But a Trudeau or a Mulcair administration would construe this relationship in a very different way than Harper and the federal Tories have in ten years of holding power.

Rachel Notley’s victory has led to an exuberant outpouring among the Canadian left, with T-shirts bearing the legend “Notley Crue” being widely sported, and with supporters delighting in Nutley’s initial gestures, including a historic acknowledgement of the province’s Indigenous people The large intake of inexperienced legislators, though, means that Notley’s government will perhaps have an awkward adaptation to holding office. Thus there should be a bit of caution in any of the auguries stemming from the Alberta convulsion. The Alberta election results stemmed largely from local factors and a frustration with a party that had stayed in power much too long to suit a democratic electorate. Yet it is also a token of a rising progressive and socially activist spirit among a Canada that is changing culturally and demographically, and a popular revolt that, across the globe, is defying neoliberal prescriptions of austerity and favoritism towards the wealthy, and demanding a more responsive governance.

As such, this provincial election on the prairies could lead to far wider and more fundamental hemispheric implications.

By: Nicholas Birns, Senior Research Fellow at COHA; His book on contemporary Australian literature and neoliberalism will be out from Sydney University press in September.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

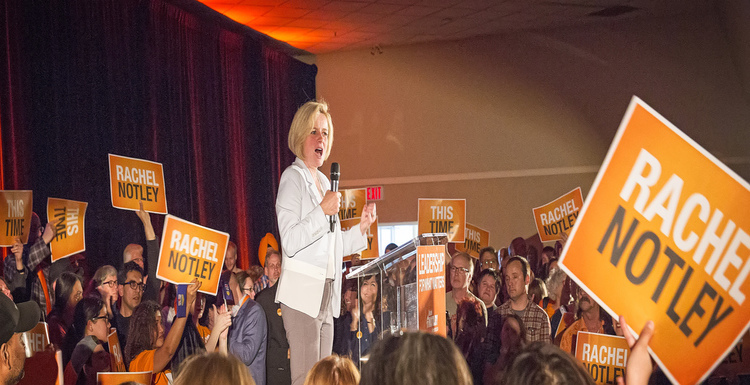

Featured Image: Rachel Notley. By Don Voaklander. Retrieved from Flikr Creative Commons https://www.flickr.com/photos/donvoaklander/17360638461/in/photolist-72auAG-726utK-72aw9E-cpVaZs-spQpqw-srXx1S-ss8mzp-ss8GB8-s8NF34-srXTAj-saFcHZ-spQgHN-sawSQ3-rvjyJk-spQGTh-saFDrn-ss6NYM-saF7ae-saxgSW-sawKRd-s8NJe4-rv7UvQ-ss6qST-rv7Z4Y-srY36W-saxo6C-sax6QS-sawTXy-rvjQo6-rv7LDs-6dsoKu-s8pDwQ-s1zTZp-saQa7Z