Scientific Progress at an Inhuman Cost

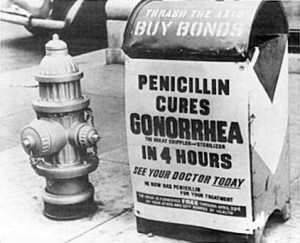

From 1946 to 1948, the United States conducted medical research in Guatemala to determine the effectiveness of penicillin in preventing and treating sexually transmitted diseases, including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid. To carry out their study, U.S. researchers knowingly infected Guatemalan prisoners, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and soldiers with multiple illnesses by means of experimental inoculations and direct contact with infected participants. More than 1,500 subjects were exposed to a variety of diseases and were given little to no information about the study. Of those infected, about 700 were treated with what was considered the modern wonder-drug, penicillin. Following the historic Nuremberg Trials in 1945-1946, a consensus on international ethics was achieved, but at the time of the Guatemalan experiments, these agreed-upon standards were not in effect.

In June 2010, Professor Susan M. Reverby of Wellesley College exposed the unethical experiments in Guatemala, relating it to the Tuskegee experiments in Alabama (1932-1972), in which African-Americans were secretly injected with syphilis-causing bacteria without informed consent. Moreover, the subjects were not effectively treated despite the existence of a penicillin treatment. The studies in both Guatemala and Tuskegee were supported by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) and were overseen by the same man, Dr. John Charles Cutler. Even worse, the experiments in Guatemala were funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Pan American Sanitary Bureau in collaboration with several Guatemalan government agencies.

Although more than sixty years have passed, archives related to the work have surfaced only recently. What were the researchers trying to hide by not publishing the study? What convinced Cutler to archive the records decades after the experiments? Professor Reverby turned up evidence that Dr. Cutler stated in a letter to PHS Physician R. C. Arnold, “we are holding our breaths, and we are explaining to the patients and others concerned with but a few key exceptions, that the treatment is a new one utilizing serum followed by penicillin. This double talk keeps me hopping at times.” In another letter, he admitted that “a few words to the wrong person here, or even at home, might wreck [the study] or parts of it.” Cutler was aware that the research was intrinsically unethical and he deliberately suppressed information.

Cutler and the other researchers on the Guatemala project infected subjects with life-threatening germs withoutinformed consent, even though an ethical standard was recognized. In 1943 and 1944, Cutler was involved in similar syphilis research performed at the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. Prisoners signed consent forms to participate in the study in exchange for commuted sentences or monetary compensation. The study was later discontinued in Terre Haute, only to soon commence in Guatemala. Cutler, as well as the other researchers and funders hoped that a life-saving discovery in Guatemala would justify the controversial scientific investigation techniques conducted in Indiana. In addition to the unconsented involvement of prisoners, soldiers, psychiatric patients and prostitutes, Guatemalan children from an orphanage and school were involved in serological experiments without their parents’ consent. Cutler and his team of practicing medical professionals knew that the experiments were at the very least highly questionable, yet they proceeded with them.

Since the original records have been unearthed, The New York Times reported that at least 83 people had died from the experiments. Because of the inconsistency of the records, a final accurate number has not been determined. In September, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues published a full report of the study. In one particular case, a woman was deliberately infected in the eyes, urethra, and rectum, even though it “appeared [that] she was going to die,” which she did soon after. Adding to the terror of the experiments, seven Guatemalan epileptic women were injected with syphilis in the back of the neck through the method of cisternal puncture to test a theory that syphilis could cure epilepsy. Two test cases had severe headaches, one was paralyzed in the legs; five received preventative penicillin after the injection, one of whom died; one did not receive treatment.

The medical studies conducted in Tuskegee, Terre Haute, and Guatemala were unethical in the extreme. Advocates for the Guatemalan parties have insisted that they deserve more than mere verbal apologies from Washington, while the U.S. cannot officially undo their actions. Some of the surviving victims and their families continue to suffer. These researchers transmitted diseases to thousands of Guatemalans without proper treatment, which brought on grievous health issues. Even though apologies are profoundly necessary, those affected must be compensated for the subsequent costs of healthcare and for their psychological and physical suffering. There is no telling what other unethical studies have been archived and are waiting to be revealed. While nothing can undo the tragedy that these victims of human subject studies endured, the U.S. should at the very least set up a fund as a means of beginning to provide redress for the cases that have since surfaced.

This analysis was prepared by COHA Research Associate Linnea LaMon