Reexamining the U.S.-Honduran Relationship

Last March, U.S.-Honduran relations came under studied scrutiny after Representative Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) and 93 other House members sent a letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton advocating an across-the-board cutoff of all military and security aid to Honduras. In the Senate, Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) and six of her colleagues wrote a complementary letter to express their growing concern over whether Honduran authorities were acting in full accordance with the provisions of FY 2012’s appropriations bill. The House proposal and the Senators’ associated concerns have emerged in reaction to Honduras’ enduring shabby human rights record, which has been stained by near-daily violations dating back to the 2009 coup against constitutionalist president Manuel Zelaya and the subsequent installment of a golpista regime. Since then, Honduran security forces have been in the international hot seat for using excessive force against demonstrators and standing idly by as the country’s civilian death toll has mounted.

Human rights organizations have highlighted the volatility which so plagues the country by underscoring the fact that at least 22 journalists have been murdered in Honduras over the past two years. Indicative of an overall lack of public safety, these killings have effectively deterred many reporters from inquiring into the country’s rampant corruption and human rights abuses, staunching media efforts to expose such issues. Indeed, the situation is made worse by the fact that many of the slain journalists were targeted for either openly expressing their disapproval of the 2009 coup, or because they actively reported on the human rights abuses made so ubiquitous in Honduras after the overthrow. Impunity, rural violence, attacks on journalists and LGBT community members, and a lack of respect for civil liberties are among the factors behind the relatively large number of casualties cited in the Congressmen’s letters, which evoked questions as to whether Honduran authorities are apportioning U.S. aid appropriately.

Honduran government officials, meanwhile, have been dismissive of all speculation over whether the attacks on journalists were related to the victims’ journalistic endeavors. The fact that civil liberties as basic as freedom of press and assembly have been so thoroughly undermined makes it apparent that the attainment of authentic democracy, rather than the simulacrum presently masquerading in Tegucigalpa, is, at this point, a lofty goal. The current administration in Honduras has failed to offer an explanation for the myriad of post-coup abuses, and conflict between supporters of the current regime and advocates of the ousted Manuel Zelaya continues to afflict Honduras.

Washington, for its part, has been quietly providing Honduras with security aid for the last 16 years, though in 2011, a Gallup poll reported that only 31 percent of Hondurans believe the Obama administration to be doing an adequate job of strengthening ties between the United States and Honduras, an indication of the dwindling impact of U.S. leadership in the region. One must question the stance taken by the State Department in response to a regime installed in the wake of an anti-democratic coup. A sizable portion of the Honduran electorate is fervently opposed to any government with golpista origins, but their public protests are routinely doused, even when the remonstrating citizens pose no danger to Honduran society. The United States claims to champion core democratic values at the international level, yet it has, with Honduras, continued to back a country whose supposedly democratic foundation leaves much to be desired.

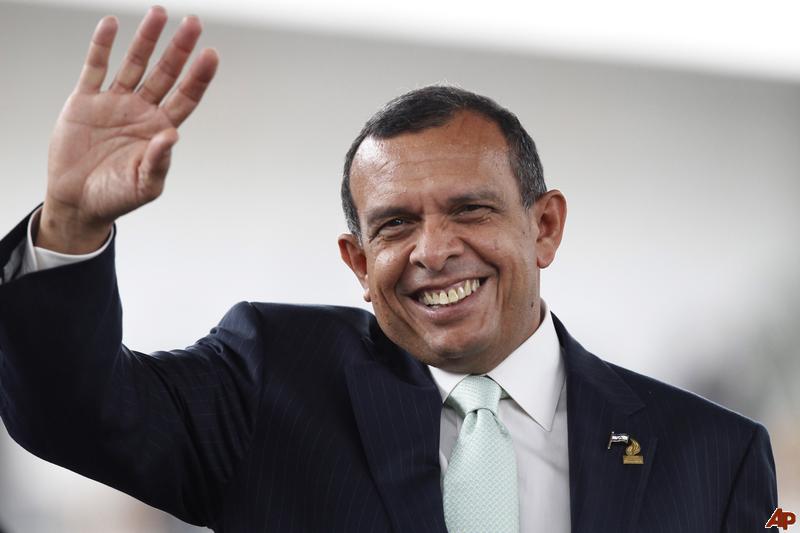

According to the State Department, the United States’ mission in the country is to “support… democracy and respect for human rights.” Under President Porfirio Lobo’s administration, however, claims that a true democratic system has been implemented, or that the United States has adequately responded to the reprehensible actions of Honduran security forces, are questionable at best. The U.S. Human Rights and Labor Attaché, Jeremy Spector, has even gone so far as to label dissenting citizens “thugs.” Instead of holding Honduran military and police officials responsible for the social discord which became so commonplace after the coup, Washington has vilified demonstrators expressing their dissatisfaction with the Lobo regime.

In March 2012, President Lobo received his lowest approval rating since his inauguration two years ago: a dismal 4.6 out of 10, down from the 5.11 rating he received last year. During his presidential campaign, Mr. Lobo vowed to reinvigorate state security. Yet two years after the coup, Honduras now ranks as the hemisphere’s most dangerous country. It appears that while the Honduran state has failed to quell violent crimes, it has been particularly successful at silencing journalists, denying the citizenry of its constitutional right of access to information. The current leaders of Honduras have consistently demonstrated that they are motivated more by self-interest than democratic principles, and yet Washington’s support continues, unabated.

To be sure, eliminating aid to Honduras wholesale would pose certain challenges. Inarguably, much of the Western Hemisphere, faced with numerous security crises and an insidious volatility induced by organized crime, drug traffickers, and the unrelenting violence of street gangs, has come to depend upon a certain amount of U.S. assistance. Cutting off aid to Honduras could enable foreign drug cartels to flourish even more than they already do under the present status quo, in which virtually the entirety of the Honduran prison system is inundated by imprisoned gang members. With the cessation of U.S. aid, the flow of drugs from Central America to Mexico and the United States could very well increase, potentially leading to a spike in rates of drug abuse and crime throughout the region. An astounding 84 percent of South American cocaine passes through Central America before making its way into the United States; the trafficking of illicit drugs is a significant hemispheric hazard that must not be overlooked. Thus, if the United States were to halt aid to Honduras, it would have to maintain its commitments to other Central American countries so as to combat the expansion of Latin America’s cartels.

As is, the United States has invested much in Honduras as a launching point for the implementation of the Central American Regional Security Initiative, an effort to combat criminal activity and promote a more stable social order throughout the region. In light of the persistent turmoil in Honduras, however, it appears as though this initiative—which has cost American taxpayers upwards of $260 million since its inception—has been ineffective at curbing the appalling amount of violence perpetuated by Honduran military and police forces, the very groups theoretically responsible for cracking down on such bloodshed. Violence racks the country now more than ever, with gang-related incidents driving much of the country’s appallingly high murder rate, which, according to the United Nations, stands at 82.1 per 100,000 people—the highest per capita homicide rate in the world. Further, the Honduran government has neglected to investigate a rash of crimes, some of which involve military and police personnel accused of a broad range of violent transgressions, demonstrating a serious lack of democratic capacity and calling into question its ability to function without being propped up by U.S. aid.

Still, Honduras, due in no small part to U.S. assistance, has made steady improvement over the years in terms of sustainable economic growth and rates of primary school graduation and maternal mortality. American initiatives, including USAID’s “Feed the Future” program, which aims to cut extreme poverty in half by 2015, have ambitious goals, and, in Honduras, are often successful in meeting them. The U.S., for instance, has been heavily involved in repairing the Honduran economy, with its twin maladies of high underemployment and wide income disparity, and according to the CIA World Factbook, “nearly half of Honduras’ economic activity is directly tied to the U.S., with exports to the U.S. accounting for 30% of GDP and remittances for another 20%.” The importance of U.S. development aid to Honduras cannot be discounted.

After experiencing Central America’s first coup d’état in over 25 years, Honduras is more vulnerable than ever, and action must be taken. Without due diligence, Honduras could well become a permanent sanctuary for narcotraffickers, or become further marred by government-approved violence. If the United States insists on continuing to fund Honduran security forces, then a better oversight system must be implemented.

On the other hand, were Washington to cut off security aid entirely, Honduras would assuredly retain its dubious distinction as a nation of human rights disasters, unrelenting drug trafficking, and strikingly undemocratic “democracy.” As things stand today, Washington continues to support the unequivocally corrupt Lobo administration thanks largely to the American airbase in Honduras which is so central to U.S. military strategy in the region, and the influence of Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.), chairwoman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. The Republican legislator, alongside her Cuban American constituency, has co-opted the State Department into backing the Lobo administration. Such influence, a kind of coup in itself, cannot be allowed to go on unchecked.

Ultimately, Washington must decide whether continuing to support an oppressive regime is truly in the best interests of the Honduran people. So, too, must it consider the good its development aid has done, and what, if anything, the impact of its security assistance has been. Whatever the decision, one thing is certain: the U.S. must reevaluate the nature of its Honduras policy.

To read more about Honduras, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.