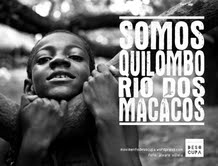

Quilombo do Rio do Macaco: A Growing Military Presence Places One Brazilian Community at Risk

The late Afro-Brazilian scholar Abdias do Nascimento set a unique flame to Brazil’s quilombos, or maroon colonies, which had been established by runaway slaves as well as free people, in many of his writings. He described them as the result of the “vital exigency for enslaved Africans to recover their liberty and human dignity through escape from captivity, organizing viable free societies on Brazilian territory,” and used quilombos as the basis for his ideology of resistance against racial oppression. Nascimento’s writings express admiration for the collectivism and independence characteristic of these communities, which exist nationwide.

By and large, these locales developed as autonomous pockets, to be found deep within Brazil’s interior and free from colonial or imperial control. To this end, quilombos have been the subject of much debate in Brazil, especially with regard to minorities’ land rights. Beginning in the early 1980s, activists like Nascimento argued for the recognition of these communities, and brought their status as neglected “historic sanctuaries” to public attention.(1)

On June 5, residents of one Bahian quilombo clashed with members of Brazil’s military. The inhabitants of Quilombo do Rio do Macaco drew media attention as officials from the Aratu Naval Base encroached on the community’s fringes. Residents were deprived of access to basic resources such as electricity and potable water, while Navy officials restricted travel to and from the quilombo. Unsurprisingly, the community has yet to be officially designated a quilombo by the Brazilian government, preventing inhabitants from living there as free quilombolos, or inhabitants of quilombos, according to Articles 215 and 216 of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution.

Here Comes the Navy

Beatriz Mendes, a writer for the Brazilian news magazine Carta Capital, traces the origins of the present conflict to the mid-1950s. According to Mendes, the city of Salvador donated land surrounding Quilombo do Rio do Macaco to the Brazilian Navy in 1954. Shortly after this exchange of land, the military erected a dam on the River Macaco, and during the 1970s authorities constructed a naval base to house marines on the acquired territory. The construction of the naval base displaced approximately 60 families, effectively souring relations between the community and the military facilities.(2)

Current residents of Rio do Macaco are generally the third or fourth generations to call this area of Bahia home. A video released by a sympathetic blog following the conflict, titled “Bahia na Rede” (Bahia on the Net), emphasizes the quilombo’s unique history as an autonomous community and claims to the land.(3) One resident speaks of how his parents, grandmother, and great-grandmother were born in Rio do Macaco. Another woman in the video traces her ties to the community centuries back, referencing her grandmother of 111 years of age.

Despite the inhabitants’ compelling histories, however, officials defend the base’s existence. The Navy maintains that the base was constructed for the sole purpose of “logistic support for the naval, air, and marine forces of the Brazilian Navy stationed at Aratu or in transit.”(4) Many military officials continue to deny any future plans for unlawfully dislocating additional residents.

Regardless, marines are little better than an occupying force that has repressed quilombolo life for decades. The documentary produced by Bahia na Rede captures the utter terror that villagers experience. As one woman describes, “At night no one can rest. No one is sure they will make it to the morning. ”(5)

Constant Threat

Beginning in 2010, the military developed a program of indiscriminate land appropriation. According to Beatriz Mendes at Carta Capital, the Navy filed a lawsuit in the federal court system to affect its claims through the Attorney General’s Office in an attempt to seize the quilombo’s territory. The Navy plans to relocate the residents of Rio do Macaco and cultivate the appropriated territories for the military’s needs. Naturally, this has resulted in the mobilization of quilombo residents, who earlier this year protested at the Aratu naval base. Interestingly, President Rousseff perused local beaches on the base during her holiday, and locals have vehemently criticized her for ignoring their pleas.(6)

Support from NGOs and independent human rights activists have postponed the repossession of these territories until August of this year, thereby offering quilombolos ample time to develop their own case before the public. Organizations such as the Palmares Foundation and the National Institute of Colonization and Reform (INCRA) support the community and declare Rio do Macaco a rightful quilombo under the 1988 Constitution. Consequently, residents of Rio do Macaco can now submit pleas for official government recognition and invoke Article 215 of the Constitution, which specifically protects indigenous and Afro-Brazilian land rights. Without official government recognition of the quilombo, residents are virtually hopeless in the face of military oppression.

On June 4, Guellwar Adun, an apologist for the quilombolo cause, posted a series of photos on Bahia na Rede. These photos include portraits of the local community and highlighted bullets that farmers found near the village. An accompanying post said, “What we see here is a shame for a nation that aspires to democratic ideals. We must act so that our government will respond!”(7) Unattributed text also referred to controversial policies whereby marines prevent any construction in the community that they have not authorized.

Federal Judge Evandro Reimão dos Reis of the 10th circuit in Bahia supported these claims, and prohibited construction in the territories comprising Quilombo Rio do Macaco.(8) These policies culminated in the events of May 28, which quilombolos have used as a new focal point for their protests. According to Bahia na Rede and Cedefes, armed militants invaded the quilombo and prevented the reconstruction of resident Jose de Araujo’s home. Their violent tactics and complete disregard for residents’ rights reveal the roots of the widespread panic prevalent in this part of Bahia.

In turn, Commander Queiroz of the 2nd Naval District has officially declared, “The construction of this building without authorization demands intervention of the courts. … Here lies an undefined community, which irregularly occupies these territories.(9) The military’s failure to recognize quilombolo land rights constitutes, as many activists point out, a direct violation of local residents’ sovereignty and basic human rights. Jose de Araujo added, “This is unacceptable, this isn’t living … a crime against humanity.”(10)

Other violations include seizure of the local postal services and regular intimidation by armed officials. More specifically, representatives for INCRA blame the Navy’s austere travel restrictions to and from Rio do Macaco on the civilian residents’ inability to effectively develop their case. Inhabitants are often prevented from leaving the territory to plead their case and supportive organizations are prevented from breaching the base.

Response

The events at Rio do Macaco have attracted a great deal of attention, in many ways reflecting the government’s misguided policies regarding minorities in Brazil. On May 2, residents traveled to Brasilia to present their case to the Committee of Human Rights and Minorities. According to the Parliamentary Advisory of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party), these quilombolos submitted official records that documented a history of aggression on the part of the Marines and military officials stationed at Aratu. Many of their claims described an “intolerable situation … with fear that the worst has yet to come.”(11)

Earlier protests pleading for assistance have finally garnered attention. More recently, representatives for the Committee of Human Rights (CDH) and the Minority of the Chamber of Deputies in Bahia have arrived to investigate the case. In Rio do Macaco, committee members heard the case of quilombolos in a public forum, accompanied by several other important government and NGO officials. To date, no official resolution has been reached, although the CDH has tried to facilitate dialogue between the military and locals of Rio do Macaco. Representatives also have pointed to the culpability of the Attorney General’s Office regarding the conflict, especially for hearing the apparently unjustified claims of the military.

By contrast, the military insists that residents are exaggerating their case. Commander Queiroz has argued once more that it is conventional for marines to carry out armed patrol, given it is a military base. Although no official calendar has been made, some Navy representatives have expressed plans to convert other territories comprising the Rio do Macaco zone into residential buildings and a hospital for marines.(12) Certainly, these projects would demand the relocation of the 500 quilombolos of Rio do Macaco.(13) The relocation of these people is not a viable option, however, and they are not yet willing to leave. Quilombolos of the Rio do Macaco region have lived there for more than a century, and have laid claims to the land long before the arrival of the military. If nothing else, one possibility would be for the Navy to abandon the base and return appropriated territories to these people.

In essence, this is very much a humanitarian issue. Critics insist that the military has robbed these people of their rights as citizens, and Brazil’s sluggish judicial system has allowed officials to take advantage of the community’s uncertain legal status. As long as Rio do Macaco retains this liminal status, Marines will almost certainly continue to encroach on these territories and ultimately force these marginalized groups from their land.

As Brazil continues to democratize, the government should take stronger measures to defend the rights of its citizens against endemic military aggression. This is especially crucial when it comes to historically oppressed populations. Attacks on rural populations such as those dwelling in Rio do Macaco constitute violations of constitutional rights and ought to be prosecuted as such. The matter deserves greater international media coverage so as to pressure the Brazilian government to take action on behalf of quilombo communities.

To view citations, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.