Polar Ideologies Surface Due to Tempered Growth in South America

- Global risk aversion, primarily stemming from uncertainty surrounding the Eurozone recession, has reduced commodity demand from Asia as well as capital outflows, which has moderated growth in South America.

- While Colombia’s response to slowed growth has gravitated more towards free market principles, Brazil has demonstrated a state-active approach in seeking recovery.

- Rural communities and the agricultural sector in Colombia are expected to be negatively impacted by the elimination of tariffs due to the free trade agreement the Colombian government signed with the European Union in June 2012.

- Brazil’s response to decelerating growth has involved spurring consumer demand with stimulus packages as well as protecting domestic manufacturing industries with protectionist measures and tax breaks.

Tempered Growth in South America

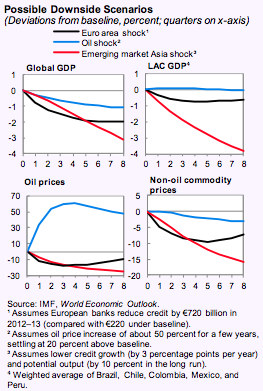

Despite its advantages, commodity export-led development eventually culminates in a gradually built-up dependency on foreign demand that can leave a domestic economy highly susceptible to foreign markets. The term ‘Dutch disease’ as coined by The Economist refers to an economic vulnerability that develops when surges of demand in select raw commodities appreciate the local currency. The subsequent rise in export prices makes other sectors less competitive and renders commodity demand a governor of growth.[1] This is a situation South American economies, specifically Brazil, Peru, and Chile, are facing due to China’s slowing economy. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a decrease in demand from Asia would have the greatest economic impact of any potential spillover shock in Latin America, even more than a further deterioration of the debt crisis in Europe.[2] Uncertainty shrouds global economic activity, posing dangers of diminishing export revenues, larger current account deficits and capital outflows – political incumbents have in many cases faced the ‘Protectionist Dilemma.’[3]

Brazil and Colombia have approached this trade-off in different ways. Since July, Colombia has loosened its monetary policy by cutting interest rates to stimulate growth, seeking to ease currency appreciation by deepening currency reserves through a 20 million USD daily dollar-purchasing regime adopted in March that has been supplemented with additional lump purchases.[4] In June, Colombia also deepened its commitment to free trade liberalization with the ratification of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the European Union (EU). Meanwhile, Brazil has attempted to encourage consumption and investment through a series of macroeconomic policy adjustments and stimulus packages. President Dilma Rousseff’s administration has also demonstrated its familiar preference for protectionism over sustained foreign competition and deindustrialization. Its trade association with Venezuela, now under Mercosur, is yet another indication of the government’s focus on collaborative state-led ventures.

While Colombia has pursued trade liberalization and accepted the inherent characteristics of its economy, Brazil has sought to transform its trade structure by using protectionist measures to protect domestic industries, and also by adopting select industrial policy to aid them. Colombia’s economic policy has focused on deregulation, trade liberalization, fiscal consolidation, and the promotion of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI); a set of measures that echo the decrees of the ‘Washington Consensus.’[5] A term first used by economist John Williamson in 1989, the Washington Consensus were a set of prescriptions that described the economic policies the IMF, World Bank, and US Treasury Department believed were necessary to help lift Latin American countries out of their economic crises. The consensus has since been discarded to different degrees by governments of South America. This has coincided with a resurgence and growth of a strategy labeled by economist Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira as ‘neo-developmentalism,’[6] in which the state is appointed as the primary agent to lead a nation’s economic development. Whether through trade protectionism, nationalization or the subsidization of industries, Argentina and Venezuela have most fervently demonstrated neo-developmentalist tendencies. Brazil has rather sought the most balanced prescription of economic orthodoxy and neo-developmentalist rationality.

Spurring Economic Growth in Colombia

Colombia witnessed its first interest rate cut in two years after central bank board members voted to drop the rate to 5 percent (now 4.75) on July 27, 2012.[7] The Andean country now joins the expanding group of states, which includes India, China, Brazil and the EU, who within the last five months have all responded in similar vein. Unlike Brazil and other commodity exporting economies in South America that are being negatively affected by decreased demand from Asia, Colombia’s markets are more dependent on US consumption; Colombia exports only 3 percent of its goods to China as oppose to 38 percent to the U.S.[8] The slowdown in China’s economy has therefore impacted Colombia’s growth prospects less severly. Nonetheless, the country follows a commodity-exporting led model that is vulnerable to shifts in demand. Mindful of this vulnerability and the simultaneous strengthening of the Colombian peso, the benchmark interest rate has been lowered to boost export competitiveness for Colombia’s coal and oil energy sectors.

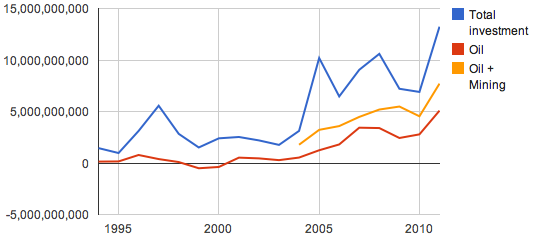

Judging from former finance minister Carlos Echeverry’s comments regarding Colombia’s economic aspirations, it seems that establishing investor confidence has been one of the principal goals of the country’s economic policies. Improved domestic security conditions and deregulation have been rewarded with continued upgrades to the country’s investment status since 2011. Now, Colombia’s maturing business climate is attracting record levels of foreign investment.[9] While the flow of certain goods and services in Brazil has entrenched itself in protectionist measures, Colombia has demonstrated that its economy is one of the most open in South America. On the surface, the country’s persistence with the free market approach seems to be paying off. The rising rate of FDI is one stark indicator of greater investor confidence. FDI inflows that amounted to 7 billion USD in 2010 are forecasted to reach 17 billion this year which, although somewhat optimistic, are comparable to levels of FDI seen in Chile and Mexico.[10] It remains to be seen to what degree higher rates of FDI will be directed outside the scope of the oil and mining sectors.

Source: Colombia Reports

Adherence to Open Market Principles

Whereas Brazil’s state-led interventions have in some cases produced uneven gains and alienated neighbors, Colombia’s free market approach has encouraged greater regional trade solidarity with the creation of the Pacific Alliance in 2011. Deemed as “the most significant integration process in Latin America,”[11] by President Juan Manuel Santos, the Pacific Alliance follows a clearly different path than Mercosur’s. Not restricted to a common trade policy, the countries that compose the Pacific Alliance are able to pursue trade liberalization on a bilateral basis through FTAs. As a result, they are much less inhibited in implementing measures to increase their competitiveness, levels of employment and economic growth. The wave of trade liberalization isn’t showing signs of dissipating either; the US FTA with Panama and Colombia, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the recent EU-Peru/Colombia FTA are a sampling of the latest agreements that will structure economic growth in the region.

EU-Peru/Colombia Free Trade Agreement

While public debt burdens and tamed growth continue to constrain advanced economies, producers and investors have been looking for ways to make inroads into emerging foreign economies. Further expansion into foreign markets, including those in Latin American countries, would contribute up to 90 percent of the EU’s growth, according to EU Trade commissioner Karel De Gucht.[12] Five years after the negotiations began in 2007, the trade union now stands to level the playing field after the formal signing the EU-Peru/Colombia FTA on June 26, 2012.

By creating opportunities for European firms in a variety of sector, including: mining, energy production, infrastructure development, manufacturing and services, the agreement is expected to proliferate bilateral trade that reached 26 billion USD in 2011.[13] The EU expects to save nearly 314 million USD from the elimination of customs duties. European exporters of car parts are expected to save 40 million USD, exporters of chemicals are expected to save 20 million USD, and exporters of textiles are expected to save 73 million USD.[14],[15] Meanwhile both Colombia and Peru’s economies are expected to receive welcomed boosts to their GDP growth as a result of the FTA.

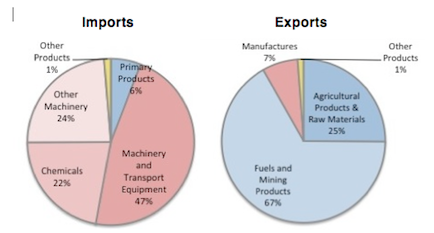

Data: EU Trade Commission

While Colombia occupies a small share of the EU’s total trade volume, for the South American nation, the EU is among the biggest sources of its trade income. Primary products account for 92 percent of Colombian exports to the EU, the majority of which are minerals, mining products and agricultural products. Conversely, manufactures account for 90 percent of Colombian imports, the majority of which are transport and machinery imports followed by chemicals. EU manufacturers and extractors can expect to benefit from technical regulations that, once implemented, will facilitate exports of other sophisticated machinery and pharmaceuticals previously prevented by trade barriers.

Nevertheless, the unregulated exploitation of land and labor resources by foreign companies that could follow the liberalization of trade and tariffs is one of the prevailing concerns for Colombia’s agricultural sector and resource-dependent rural communities. The EU satisfies half of its energy needs through imported raw materials and by 2030, its demand for energy imports is expected to rise to 65 percent.[16] Meeting its 10 percent quota for agro fuels for the predicted consumption would require 2.5-3 million hectares of land for sugar cane and palm oil production.[17] While there are gains to be made from the development of Colombia’s ethanol industry, they may come at the cost of exhausting natural resources and causing displacement of rural communities as the country’s tropical expanses potentially bear the brunt of such an appetite for tariff free agro fuels.

By leveling the playing field, the unrestricted influx of agricultural imports will likely harm Colombia’s domestic agriculture. Farmers who were already competing against heavily subsidized U.S. agriculture will now have to deal with the EU, which under its Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) subsidizes its agriculture industry with up to 67 billion USD; almost half of the EU’s annual budget.[18] The risk is if farmers get priced out, they will be constricted to cultivating select cash crops such as bananas, fruit, coffee, flowers or even cocaine, opening the way for Colombia to become a prominent importer of foods. This is just one of the many asymmetries between both economies, which suggest that outward pressures could be too great to encourage diversification.

To offset the impact of the country’s trade liberalization, the Colombian government is doing what it can to subsidize farmers. In May, the Minister of Agriculture, Juan Camilo Restrepo Salazar announced a 571 million USD subsidy package to provide farmers with sufficient resources to boost “crop yields, improve livestock genetics and overhaul farms.”[19] In August, Congress also received a bill aimed at creating a family compensation fund for small farmers.[20]

However under a FTA framework, Colombia’s capacity to compensate for market failures and its ability to implement policies to either protect certain sectors or reverse rural unemployment will be limited. Market forces will instead focus Colombia’s economy on sugar, palm oil production and mining, thus further deepening the dependency on commodity export-led growth. The Santos administration remains satisfied that increased market access to commodities and greater investment in the procurement of those commodities will bode well for the nation’s primary engine for economic growth.

Taxing Trade Frictions Within Mercosur

Following the ratification of the EU-Peru/Colombia FTA, the EU trade commissioner used the occasion to promote an open market framework for South American economies. According to the trade commissioner, only in this way will the region be able to diversify to produce value-added goods and build on the success of the its commodity exports. However, while global markets remain volatile, domestic political pressure continues to provoke state intervention and export activism from states like Argentina and Brazil, particularly as multilateral avenues for settling trade disputes like the WTO have been tedious.

Given the circumstances, Argentina and Brazil have leveled non-tariff measures against each other only to the detriment of their bilateral export volumes. Argentine restrictions for automatic import licensing on up to 600 items have been causing delays and losses for Brazilian exporters since the beginning of the year.[21] Brazil then retaliated in May when it ended automatic import licensing for several categories of perishables of which Argentina is a major exporter. That means that up to 70 percent of Argentine exports to Brazil now require license applications that can take up to a month to process.[22] Such trade frictions are hardly ideal for two of the biggest Mercosur markets that depend so much on each other; bilateral trade between the two reached 39.6 billion USD in 2011.[23]

Stimulus Measures and Rising Credit in Brazil

While retaliatory protectionist measures against Argentina, and Venezuela’s incorporation into Mercosur have emphasized Brazil’s recent headstrong regional economic policy, on a domestic level, the country’s responses to decelerating growth have revolved around two objectives; the first being to stimulate consumer demand. Consistent cuts to the benchmark interest rate by the Brazilian central bank to a current record low of 7.5 percent[24] and a reduction of reserve requirements that has freed up 18 billion USD, have been fed into the system to loosen the supply of hard currency and stimulate consumption.[25] However, rising credit burdens indicate that efforts to stimulate consumer demand may only produce a marginal impact. Brazilian households are currently allocating over one third of their income to debt payments and default rates were otherwise at a 30-month high in July.[26],[27] While private debt levels may not be an immediate concern, fast credit growth without proper supervision of lending standards will create market bubbles with the same disastrous consequences witnessed in the U.S. and Europe.

In addition to spurring greater domestic consumption, prompting the manufacturing sector to purchase and produce within the country has represented the second preoccupation of Brazil’s Ministry of Finance. The effort to reverse deindustrialization has spanned two years, marked by several stimulus packages totaling 51 billion USD.[28] Although industrial production has been gradually contracting, recent figures indicate a reversal may be occurring due to a series of macroeconomic policy tools that have been utilized by the central bank. In the face of sluggish growth, the automobile sector, which encompasses 20 percent of industrial GDP,[29] was directly supported in May by a temporary reduction of the IPI (industrial product) tax.[30] As a result, carmakers were able to make marginal cuts to retail prices witnessing some degree of success after a record number of automobile sales in July.[31]Rousseff’s administration intends to go further with a stimulus package of 3.2 billion USD to spend on public transport vehicles, defense equipment, and construction vehicles by year’s end.[32] However, in spite of recent state-led stimulus efforts, Brazil’s cost competitiveness will require ongoing attention. High wages and tax burdens for employers combined with infrastructure deficits are a of collection familiar challenges that are keeping production costs high and will likely handicap any substantive revival in the manufacturing sector.

Conclusions

Due to the uncertainty surrounding global markets and the reduction in demand for commodities, South American economies have demonstrated varying responses to decelerating growth. Colombia and Brazil have established accommodative monetary policies to achieve greater domestic consumption and higher export volumes, though both countries have sought competitive advantage in distinct ways.

Despite market volatility, the principal tenant of Colombia’s economic policy has been the establishment of a transparent and non-discriminatory environment for the exchange of goods and services as a means to foster economic growth and competitive advantage; the country’s growing collection of FTAs are evidence of this. As the Colombian economy adjusts to the U.S.-Colombia FTA, the initial feedback has been positive. Trade Minister Sergio-Diaz Granados recently revealed that Colombian manufacturing exports rose by 70 percent in the first two months since the agreement took effect in May 2012.[33] He has also been bullish about the country’s potential to supplant China in producing textile and plastic products at a cheaper cost to give Colombian manufacturers the competitive edge. However, with China having long since established a firm edge on apparel and textile product sales since the suspension of the Multifibre Agreement in 2005, the trade minister’s sentiments should be taken with a grain of salt.[34]

Obviously, Colombia shares the same outlook regarding the EU free trade agreement, but by most indications, the FTA will result in asymmetrical gains that favor the EU. The development of urban and transportation infrastructure, the expansion of large-scale mining and agricultural operations are both transformative forces in their own right, but collectively can result in large displacements of populations and considerable land degradation. The FTA will suit the interests of EU businesses participating in the procurement of energy resources and delegate labor and land laws to eventually become an afterthought. It is no surprise that the arrival of large foreign corporations in Colombia has coincided with diminished civil security for trade union members and increased paramilitary interference. Another major consequence of the FTA will be a flood of heavily subsidized agriculture imports that will harm domestic farmers and threaten food security. Two million job losses in Mexico’s agriculture sector under the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) attest to this particular hazard of trade liberalization.[35]

These dangers have fostered Mercosur’s pessimism regarding trade liberalization and reinforced its neo-developmentalist ideology of the state’s role as a primary agent to lead economic development. Under this strategy, the state plays a moderate role in creating investment opportunities, with control being exercised over the utility and commodity sectors deemed strategic to development.[36] This has been demonstrated by the collaborative state-led initiatives of Argentina and Venezuela initiated thus far under Mercosur, particularly in energy exploration and production. By its nature, neo-developmentalist ideology delegates a prominent level of influence to human agencies, with one such byproduct being the proclivity for those agents to further perpetuate the status quo. For example, higher standards of social welfare achieved in the last ten years in South America due to the different degrees of departure from the Washington Consensus approach have fueled the demands of the public sector, labor unions, and private businesses. These various interests have propelled the economic agenda to where it is viewed as a popular determinant of state legitimacy. Both Kirchner and Chavez’ administrations have gravitated strongly towards neo-developmentalist ideology and drawn on economic nationalism for political gain. These motives are not so applicable to Rousseff’s administration, which has demonstrated a more pragmatic application of both neo-developmentalism and economic orthodoxy.

The demand-side stimulus measures introduced this year are an accustomed feature of Brazil’s hybrid approach. As far back as 2006, Lula’s Workers Party aimed at increasing aggregate demand with rising minimum wages, the distribution of cash transfers, and the expansion of the public sector. Additional demand-side measures have since marked Brazil’s state-active approach to addressing the structural tendencies of the economy and to promoting domestic consumption.

Industrial policy designed to protect selected industries and gain competitive advantage has marked the second pillar of Brazil’s response to slowing growth. This month, Brasília has responded to high output costs by forgoing 6.41 billion USD in tax revenue to extend tax breaks for 25 industries starting in 2013.[37] This was followed shortly by an announcement of tax cuts for electricity distributors that should help lower rates for businesses by up to 28 percent.[38] Both sets of measures highlight Brazil willingness to reduce fiscal space in order spur growth during a lethargic period.

In terms of trade policy, Rousseff’s administration is risking embroiling the country further in trade disputes. For all the benefits of raising non-tariff barriers against Argentina, the reality is that supply chains are slowing down and creating losses for producers trapped in the country’s trade wars. With recently announced tariffs on a hundred capital goods items, potentially rising to two-hundred, the unfavorable and unpredictable terms of trade that such protectionist creates will deter collaborative investment.[39]

However, elements of the Washington Consensus approach and neo-developmentalism need not be mutually exclusive, as President Rousseff has demonstrated in balancing the state’s role in the markets. The country maintains macroeconomic discipline with commitments to a flexible exchange rate that is tempered with savings; it adheres to an inflation-targeting regime with moderating interest rates; it values fiscal discipline but understands the need to implement income policy and create employment. The partial deregulation of road and railroad transportation projects also shows that the administration can accept diminishing state influence as a necessary means of achieving key infrastructure targets. This emphasizes why Brazil’s distinctive approach to neo-developmentalism and can more aptly considered what economist Cornel Ban brands as ‘liberal neo-developmentalism.’[40]

It is worth noting that protectionist tendencies are common in advanced economies. Bailout packages for private sector banks, the subsidization of agricultural industries, undervaluing currencies and quantitative easing measures have all been features of U.S. and EU economic policies. Thus, proponents of protectionism will question the incentive of adhering to international trade regulations when advanced economies themselves have bypassed such conventions. Particularly, when in some cases expansionist policies adopted by advanced economies have led to unexpected surges of capital inflows into developing ones. Yet Colombia, a free market adherent, is currently growing faster than any of the Latin American countries mentioned in this analysis. The country will soon surpass Argentina as South America’s second largest economy, depending on ones interpretation of Argentina’s exchange rate. While the Colombian emerging economy still catches-up and embraces trade liberalization, letting market forces to guide development may prove to be the most expedient option to follow. Given the market failures associated with commodity-export led development, Colombia’s economic policy could require a greater degree of state activism down the line. However, the policy space aimed at doing so could be greatly diminished by then.

Faizaan Sami, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

[1] “It’s only natural” The Economist. http://www.economist.com/node/16964094 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[2] ” Western Hemisphere: Rebuilding Strength & Flexibility.” Regional Economic Outlook April (2012).

[3] “Latin America’s Protectionist Dilemma.” AIO Media. www.aiomedia.org/noticia.php?i=00160&s=2 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[4]: Medina, Oscar and Matthew Bristow. “Colombia Government Buys $500 Million, Bypasses Central Bank.” Businessweek. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-08-22/colombia-government-buys-500-million-bypasses-central-bank (accessed September 1, 2012).

[5] Williamson, John. 2004 “A Short History of the Washington Consensus” Washington: Institute for International Economics. http://www.iie.com/publications/papers/williamson0904-2.pdf

[6] Bresser-Pereira, L.C. 2009. “From Old to New Developmentalism in Latin America” To be published in José Antonio Ocampo, ed. Handbook of Latin America Economics (Oxford University Press). December 19, 2009. http://law.wisc.edu/gls/documents/lands_canons/from_old_to_new_developmentalism_in_latin_america_bresser_pereira.pdf

[7] “Colombia’s Peso Bonds Increase After Surprise Interest-Rate Cut.” Businessweek. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-07-30/colombia-s-peso-bonds-increase-after-surprise-interest-rate-cut (accessed September 1, 2012).

[8] Valores, Caiman. “Global Headwinds Bite Deeper In Latin America As Colombia Orders First Rate Cut In 2 Years.” Seeking Alpha. seekingalpha.com/article/779291-global-headwinds-bite-deeper-in-latin-america-as-colombia-orders-first-rate-cut-in-2-years

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[9] Samper, Lucy. “Colombia, on the road to reaching record numbers in FDI .” Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo de Colombia. https://www.mincomercio.gov.co/englishmin/publicaciones.php?id=4300 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[10] Murphy, Helen. “Colombia finmin seeks prayers to ease peso gains amid record FDI.” Reuters. uk.reuters.com/article/2012/08/09/colombia-currency-echeverry-idUSL2E8J96ZL20120809

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[11] “AFP: Chile, Peru, Colombia and Mexico form ‘Pacific Alliance’.” Americas Forum. http://www.americas-forum.com/afp-chile-peru-colombia-and-mexico-form-pacific-alliance/ (accessed September 27, 2012).

[12] Chaffin, Joshua. “EU in Trade Deal With Peru & Colombia.” Financial Times. www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f3d04b56-bfab-11e1-8bf2-00144feabdc0.html#axzz21r5AAwlj

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[13] “EU signs comprehensive trade agreement with Colombia and Peru.” Europa. http://www.europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/12/690&type=HTML (accessed September 1, 2012).

[14] “EU signs comprehensive trade agreement with Colombia and Peru.” EU Trade Commission. trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=810 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[15] “Highlights of the Trade Agreement between Colombia, Peru and the European Union.” Europa. http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2011/april/tradoc_147814.pdf

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[16] “Not All Green is Good” FTA EU-Latin America. http://www.fta-eu-latinamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/agrofuels-and-FTA1.pdf

[17] “Meals per gallon: The impact of industrial biofuels on people and global hunger.” Action Aid. http://www.actionaid.org.uk/doc_lib/meals_per_gallon_final.pdf

.

[18] Nielson, Nikolaj. “EU farm subsidies remain cloaked in secrecy.” EU Observer. http://euobserver.com/economic/116211

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[19] Delgado, Diana. “Trade deal with U.S. could harm Colombia farmers.” Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-05-18/news/sns-rt-colombia-usatradel1e8ged6i-20120518_1_colombia-exports-colombian-farmers-planeta-paz (accessed September 1, 2012).

[20] “Gobierno buscará crear caja de compensación familiar para los campesinos: Minagricultura.” Caracol. www.caracol.com.co/noticias/economia/gobierno-buscara-crear-caja-de-compensacion-familiar-para-los-campesinos-minagricultura/20120826/nota/1750380.aspx

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[21] “South American integration: Mercosur RIP?” The Economist. http://www.economist.com/node/21558609 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[22] Flor, Ana. “Brazil targets Argentina with trade licenses.” Reuters. www.reuters.com/article/2012/05/15/us-brazil-argentina-trade-idUSBRE84E04G20120515

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[23] Flor, Ana. “Brazil targets Argentina with trade licenses.” Inter American Security Watch. http://interamericansecuritywatch.com/exclusive-brazil-targets-argentina-with-trade-licenses/ (accessed September 1, 2012).

[24] Cowley, Matthew. “Brazil’s Real Opens Weaker After Rate Cut; Eyes on Swaps, Fed, ECB.” Wall Street Journal. online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20120830-708888.html

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[25] Barrucho, Luís Guilherme. “Entenda as medidas do governo para estimular a economia.” BBC. www.bbc.co.uk/portuguese/noticias/2012/05/120528_entenda_medidas_governo.shtml

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[26] Glickhouse, Rachel. “Brazil’s growing middle class debt.” CSN Monitor. www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/Latin-America-Monitor/2012/0711/Brazil-s-growing-middle-class-debt

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[27] “Time to adapt the model, says government policy advisors.” Latin American Economy & Business (July 2012)

[28] “Time to adapt the model, says government policy advisors.” Latin American Economy & Business (July 2012)

[29] Barrucho, Luís Guilherme. “Entenda as medidas do governo para estimular a economia.” BBC. www.bbc.co.uk/portuguese/noticias/2012/05/120528_entenda_medidas_governo.shtml

(accessed September 1, 2012).

[30] Otoni, Luciana, and Tiago Pariz. “Brazil makes new tax cuts to revive economy.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/05/22/us-brazil-economy-idUSBRE84L02G20120522 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[31] “Brazil car sales surge 22 pct to July record-group.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/08/02/autos-brazil-idUSL2E8J1L6R20120802 (accessed September 1, 2012).

[32] “Time to adapt the model, says government policy advisors.” Latin American Economy & Business (July 2012)

[33] “FTA with US already benefits Colombia: Minister – Colombia news.” Colombia Reports. http://colombiareports.com/colombia-news/economy/25518-fta-with-us-already-benefits-colombia-minister.html (accessed September 1, 2012).

[34] “Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) Definition.” Investopedia. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/multi-fiber-arrangement.asp (accessed September 1, 2012).

[35] Gallagher, Kevin. “The end of the ‘Washington consensus.'” The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/cifamerica/2011/mar/07/china-usa (accessed September 1, 2012).

[36] Ban, Cornel. “Brazil’s Liberal Neo-Developmentalism: New Paradigm or Edited Orthodoxy?” forthcoming in Review of International Political Economy. http://www.watsoninstitute.org/ds/downloads/brazil_liberal_neodevelopmentalism.pdf

.

[37] “Brazilian extends tax breaks to two dozen industries to stimulate economy.” MercoPress. http://en.mercopress.com/2012/09/14/brazilian-extends-tax-breaks-to-two-dozen-industries-to-stimulate-economy (accessed September 15, 2012).

[38] Soto, Alonso, and Leonardo Goy. “Brazil cuts electricity costs to boost stalled economy.” The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/international-business/latin-american-business/brazil-cuts-electricity-costs-to-boost-stalled-economy/article4536483 (accessed September 12, 2012).

[39] “Brazil says tariff hikes not protectionist.” UPI. http://www.upi.com/Top_News/Special/2012/09/06/Brazil-says-tariff-hikes-not-protectionist/UPI-76581346949554 (accessed September 7, 2012).

[40] Ban, Cornel. “Brazil’s Liberal Neo-Developmentalism: New Paradigm or Edited Orthodoxy?” forthcoming in Review of International Political Economy. http://www.watsoninstitute.org/ds/downloads/brazil_liberal_neodevelopmentalism.pdf

.