Paraguay Makes Step Forward for Women’s and Indigenous Rights

Traditionally, the forces of conservatism and Catholicism have dominated much of Paraguayan society. However, the nation’s efforts to secure rights for both women and indigenous peoples at a recent June 9th U.N. conference in Geneva, Switzerland provides evidence for a refreshing and progressive step forward.

Paraguay: Demographics and History of Conflict

According to recent data reported by the World Bank, women comprise 74% of the Paraguayan workforce.1 Women occupy the majority throughout the country in terms of workforce population, yet relative to men they have traditionally enjoyed only restricted rights, especially in sensitive areas such as birth control and abortion. Although various feminist organizations in the country conducted awareness-raising campaigns throughout the early 1990s that led to the constitution’s most recent revision in 1992, the Paraguayan constitution still provides only scant protection for the country’s women.

Luckily, the 1992 revision implemented a “family code” in the Paraguayan constitution that gave men and women equal rights within the household, particularly with regards to parental authority.2 The code established 16 as the legal marriageable age, and provided both men and women with equal inheritance rights.3 Among other government-sponsored initiatives to combat violence against women have been the incorporation of sexual harassment into the labor code of 1996, and the modification of the constitutional Criminal Code to include references categorizing violence against women (VAW) as a federal crime.4

Paraguay’s Persistent Human Rights Abuses

Yet despite previous legislative successes in the broad struggle for women’s rights, various aspects of discrimination remain. Laws that purportedly protect women’s rights are weak, and therefore not always effective. Violence against women remains the primary infringement of women’s rights today.5 For example, recent legislation has classified domestic violence as a punishable offense, but only when the violence is strictly physical. It does not protect against psychological, emotional, or economic forms of abuse.6 Additionally, a Paraguayan woman must suffer habitual violence before she can seek legal protection.7 Such inane policies have contributed to the growing marginalization of women throughout Paraguay, the effects of which are still being seen today.

Another persistent problem has been the acknowledgement of the rights of indigenous people inhabiting different regions of Paraguay. According to Paraguay’s General Directorate of Statistics, Surveys, and Censuses, there are over 100,000 indigenous people in the country belonging to 20 ethnic groups and more than 5 language families.8 However, these indigenous peoples represent a mere 2% of the entire population of Paraguay, and these scant numbers are often the cause of why they have been the victims of continued discrimination and abuse.9 Among those most affected have been the rights of the Guarani and Chaco people, archaic bands of tribesmen who survived imperialistic exploits of the Spaniards during the 16th century.

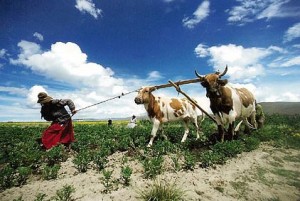

Much of the abuse towards indigenous tribes has come in the form of government mandates of forced labor, an issue which some researchers have extensively documented. In fact, the International Labor Organization (ILO) issued a report in 2005 detailing the history of debt bondage and marginalization in the

Paraguayan Chaco. The report concluded that over 8,000 indigenous workers were being forced into servitude in both rural and urban settlements.10

Still other abuses at the hands of the Paraguayan government have involved excessive and unnecessary use of deadly force against its country’s citizens and continued failure to grant further rights to their indigenous peoples. In a 2005-2006 case on indigenous rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of the Yakye Axa and Sawhoyamaxa rural communities and demanded that the Paraguayan government return the communities’ ancestral lands within a time-frame of 3 years, work towards community development in the regions, and provide better access to education and healthcare.11 However, the government has not yet granted these peoples the title deeds to the lands in question.12

Paraguay Makes Progress

Progress for the country came in late February of this year, through the process known as the Universal Practical Review (UPR), which is a basic review of human rights conducted by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) taking place every four years. At the conference, the UNCHR recommended that Paraguay “analyze the extent of illegal and unsafe abortions and introduce measures to protect the universal right of women to life and health” in order to further women’s rights in the country. Additionally, the Commission further recommended that Paraguay eliminate disparities affecting its indigenous peoples such as the Chaco and Guarani, and to allow such peoples safe returns to their ancestral lands, a claim purportedly not satisfied up until early last month.

Finally, last month, Paraguay affirmed in both word and deed that it would “open debate on the subject of abortion in depth” and commit itself to reforming its policies in other areas as well.12, 13 Reform of the country’s labor and social laws will take much time to implement, but many expect the situation to noticeably improve over the coming months.

References for this article can be found here.