Overcoming Entrenched Perceptions: Women and Leadership in Costa Rica

Examining Costa Rican leadership reveals persisting gender inequality while the country also separates itself from others thanks to its high number of women in public office. The Central American country presents an interesting case due to its long democratic history, higher ratings of gender equality compared to other Latin American countries, unique political gender quota system, and, contrastingly, its poor international standing regarding women’s leadership in the private sector. Although quotas have increased the number of Costa Rican women in public office, they have not significantly altered the social norms and challenges women encounter in pursuing leadership roles, which are preventing substantial gains for women in the private sector.

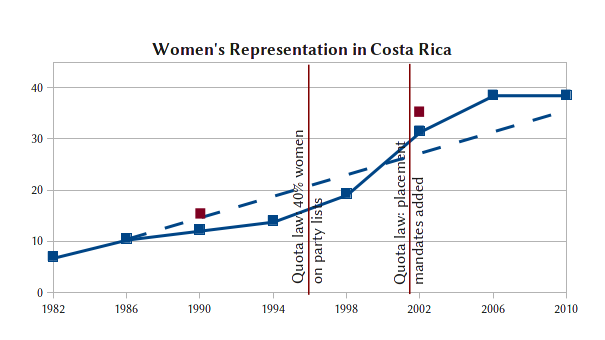

Costa Rican gender quotas were first legislated in 1996, but enforcement of the 40 percent minimum was initially weak. Various mechanisms have been implemented to administer the quotas across local and national levels of governance since they were first passed. Costa Rica will intensify its affirmative action in 2014 when a new system based on parity will be applied, suggesting that more analysis of quotas and their impact on Costa Rican governance and private sector leadership is in order.

Photo source: Tico Times

Women in Leadership Worldwide

Women working towards leadership positions face many barriers across sectors and in most global contexts. Women make up only 20.4 percent of legislative seats worldwide, and of the 500 largest corporations in the world, only 13 have a female chief executive officer. [1] Likewise, women hold only 21 percent of senior management positions globally. [2]

Widespread misperceptions of women’s inability to lead are particularly difficult to change. Both in the workplace and in the political arena, women are often viewed as less qualified and more likely to prioritize family over their careers. Women frequently adopt stereotypically male characteristics in order to be perceived as good leaders because men conventionally set the norms and standards of leadership. Across sectors, women may feel the need to show their allegiance to male elites in order to gain respect and acquire power, potentially restricting their ability to assert unique perspectives. Additionally, barriers to women’s equal participation in the labor force may limit their opportunities to ascend the chain of command. For example, the lack of universal childcare may reduce the number of hours female workers can dedicate to their jobs, especially considering the gendered breakdown of domestic and child-rearing responsibilities.

In politics, women encounter sexism within political parties and face the challenge of gathering sufficient campaign funds, but affirmative action can help address these disadvantages. In contrast, affirmative action methods are rarely employed to increase women’s leadership in the private sector. More women in leadership across sectors could help adjust the standard of male leadership while encouraging citizens and business leaders to consider the benefits of more gender-equal decision-making.

Gender Quotas in the Public Sphere

Gender quotas have been utilized in various forms throughout the world since socialist and social democratic parties in Western Europe first employed them in the 1970s. [3] Quotas generally fall into three categories: reserved seats, party quotas, and legislative quotas; all types share the goal of increasing descriptive representation of women so that the number of women in office better reflects the population’s gender breakdown. [4] Supporters of gender quotas argue that they are based on the principals of fairness and equality and that they are necessary to significantly increase women’s political representation in the near future. [5] Some also assert that increasing the number of women in power changes policy outcomes, improves the ability of women to form strategic coalitions, and potentially motivates men to address issues particularly relevant to women. [6] Furthermore, quotas symbolically impact political processes by positioning female leaders in the public eye, thus signaling that women are capable of leading. [7]

In contrast, some scholars and policymakers maintain that gender quotas discriminate against men, bring underqualified women to positions of influence, reinforce stereotypes about women’s political inferiority, and are unnecessary because qualified women will gain political power on their own merit. [8] These arguments do not take into account the structural barriers and social norms preventing women from achieving equal political participation, and thus the need for affirmative action and targeted policy changes.

Although opinions on affirmative action mechanisms differ, the ability of quotas to enhance women’s political representation depends on various characteristics of political structures and processes. For instance, legislative quotas are more compatible with proportional representation than single winner electoral systems, which are used by countries like the United States and Chile. Similarly, election processes that employ a closed-party list system, in which political parties present lists with candidates in rank-order and voters cast their ballot for the party as a whole, not individual candidates, are more likely to bring about the intended results of quotas. [9] Enforcement also plays a large role in increasing the effectiveness of quotas. For example, placement mandates on closed lists prevent political parties from clustering women at the bottom of the list where they are unlikely to be elected. [10]

Latin American countries first began imposing legislative gender quotas after women’s political representation gained international attention in the 1990s, specifically at the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. [11] Twelve Latin American countries use gender quotas today, but success varies due to political context and implementation. [12] Female Latin American politicians have explained that quotas bring about policies that better represent the interests of women and educate societies on gender-related issues. [13] Moreover, two-thirds of the Latin American public considers quotas to be beneficial for their individual countries and the region. [14] However, studies do not consistently show that quotas reach their desired results of increasing the number of women in office and bringing about legislation that accounts for gender perspectives—the understanding that gender-based differences in status and power influence short and long term interests of women and men. [15]

Quotas in Costa Rica have proven to be some of the most successful gender reforms in the hemisphere. The 1990 ‘Law for the Promotion of Women’s Social Equality’ (Law No. 7142), inspired by the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and written by feminist lawyers and activists, began the national debate on affirmative action to increase women’s political representation. Although earlier drafts of the legislation included a quota mechanism, the law’s final wording did not provide specific means for increasing representation. In response to Law 7142, several political parties amended their by-laws, but without effective implementation mechanisms. [16]

The debate continued and various proposals to amend the Electoral Code were put forward before Costa Rica adopted a minimum gender quota of 40 percent in 1996 after a push from the then-called Center for Women and Family (CWF). [17] The reform was binding for political parties, but did not specify how they should accomplish the quota’s objectives within their existing structures and did not impose sanctions on parties that failed to respect the quota. Similarly, earlier drafts of the 1996 law contained a provision that required that the 40 percent quota refer to electable positions, but the final draft did not. This meant that political parties could satisfy the quota by nominating women for positions that they had little chance of winning due to their low rank on their party’s candidate list. [18]

Once the 40 percent quota passed and the CWF organized an awareness-raising campaign, CWF officials filed a request to Costa Rica’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal to clarify how the reform would be upheld. [19] The Tribunal’s resulting decision improved enforcement by declaring that candidate lists would be turned away if they did not fulfill the minimum quota, but did not stipulate the placement of female candidates on the lists. [20] Nonetheless, the Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC) decided to alternate women and men on the municipal-level candidate lists due to pressure from the spouse of the PUSC presidential candidate, Lorena Clare Facio. [21] This measure slightly increased the number of women in public office but had limited impact due to the selective nature of non-national and internal party quotas. [22]

The 1998 election demonstrated both the potential and the weakness of the original Costa Rican quota system. While women’s representation at the municipal level increased from 14 to 34 percent, women only made up 19 percent of elected deputies in the Legislative Assembly. [23] After these results, one Costa Rican newspaper stated, “once again, the most recent elections have highlighted the strength of the customs, attitudes, and practices that have historically excluded women from decision making and the exercise of political power.” [24] The lack of regulation and the overwhelming incompliance of political parties were two major flaws of the 1996 Costa Rican quota system. [25]

Accordingly, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal took critical steps to further quota implementation in 1999. For example, Law 1863 required that the gender quota apply to electable positions and expanded the quota’s application to more public offices. [26] Additionally, Law 1863 demanded that quotas must be respected in each district, cantonal, and provincial assembly and that political parties incorporate the quota into their by-laws before the next election. Lastly, the Civil Registry took on new enforcement roles, such as refusing to register candidate lists that do not comply with the quota provisions. [27] Right before the 2002 election, the Supreme Election Tribunal took further action to impose a placement mandate requiring that women and men alternate on candidate lists, which has shown a distinct effect across parties and significantly improved adherence to the 40 percent quota. [28] The aforementioned regulations met significant resistance within political parties, demonstrating that many male elites wanted to undermine the quota system and refrain from tackling the deep-seated sexism that hampers women’s realization of their political and economic rights. Notwithstanding, the updated quota system that applied to the 2002 elections brought about significantly higher women’s political representation in Costa Rica.

In the 2002 election, women’s representation reached 35 percent in the Legislative Assembly and 47 percent in the municipalities, up from 19 percent and 34 percent, respectively. In the 2006 election, women’s representation in the Legislative Assembly increased to 38.5 percent and about 50 percent at the municipal level, percentages that changed little in the 2010 election. [29] The placement mandate, the engagement of political parties, and the Civil Registry’s ability to uphold the quota requirements were critical to the large increase. The major parties, PUSC and the National Liberation Party, have reformed their by-laws to accommodate the 40 percent minimum. Demonstrating evolving standards within political structures, the emerging Citizen Action Party internally augmented the quota to 50 percent on its own volition. [30]

The most recent set of changes to the Costa Rican quota system, passed in 2009 and set to take effect in 2014, contains the potential to bring about an equal number of men and women holding public office. The revised Electoral Code institutes the principal of parity and requires political parties to use strict alternation of men and women on their candidate lists. [31] Likewise, all delegations, electoral lists, and other bodies with even numbers must be composed of 50 percent women and 50 percent men; when the number is odd, the difference cannot be more than one person. [32] The new legislation also permanently allocates state funding for capacity building of men and women in the public sphere to enhance policymaking and ensure that women in government can fully utilize their political voice. [33]

Analyses of the Costa Rican quota system show that its engagement of political parties, application across all levels of government, and placement mandate were particularly critical to its success in increasing women’s political representation. For example, stipulations prevent districts with over 40 percent women’s representation to offset districts where the percentage is less than 40 percent, helping bring about over-compliance at municipal levels. The Costa Rican quota model has successfully increased descriptive representation of women in the public sector, but most legislation remains void of gender perspectives and machismo has not fully disappeared. Despite more women legislators and the 2010 election of Costa Rica’s first female president, Laura Chinchilla, the Costa Rican public’s idea of what it means to be a leader remains partial towards male dominance while institutional barriers and social norms continue to limit women’s leadership opportunities.

Photo source: Celebration of Women

Spillover into the Private Sector

Some may assume that groundbreaking numbers of women in government would change the society’s perceptions of women in leadership; however, persisting gender discrimination in the private sector demonstrates that this is not the case. Women make up 46 percent of public sector leadership positions in the country, yet they only make up 23 percent of private sector leadership positions. [34] Likewise, recent data collection shows that women make up 18 percent of company presidents and 31 percent of general management, signifying that opportunities for women vary drastically depending on the type of leadership position they seek. [35]

This divergence is clear when Costa Rica is compared internationally. Costa Rica ranked 29th of 132 countries in the 2012 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, tying for first place for Educational Attainment and earning 21st place for Political Empowerment. Nonetheless, Costa Rica ranks 99th for Economic Participation and Opportunity for Women, which is measured in part by counting the number of female legislators, senior officials and managers. [36]

Gender inequality at senior levels of Costa Rican private companies receives little attention, and available research is underdeveloped and absent of gender perspectives. A recent survey reported that the challenges of work-life balance and finding women with necessary qualifications remained the largest barriers to increasing the number of women in leadership positions in the private sector. [37] First, these findings do not take into account the perceptions of women in the workplace, particularly when striving for promotion. Second, finding and training qualified women is doable considering Costa Rican women’s high educational attainment. Women may demonstrate less professional experience on average, but this shortcoming is likely due to prejudices against women throughout the Costa Rican economy and the institutional barriers that impede women’s professional development.

Research by Professor Susan Clancy of INCAE Business School similarly demonstrates the lacking nature of research on female leadership within the Costa Rican private sector. Clancy found that gender stereotypes and biases, work-life conflicts, and women’s choices to have families limit their ability to gain leadership positions in the Costa Rican private sector. [38] Clancy’s research begins to account for entrenched gender inequality and predisposed views of women in leadership roles, but her analysis is not sufficient to understand or address the prevailing discrimination against women at management levels within Costa Rica’s private sector. Her research assumes that women are responsible for family matters and refrains from questioning imbalanced, gendered expectations throughout society.

Diario extra article discusses the Costa Rican Chamber of Commerce’s recent publicity efforts to elevate women leaders in society. The campaign focuses on overcoming prejudices against women in the private sector and highlights women’s leadership potential.

In the last few months, the discussion and action surrounding women’s leadership in the private sector has amplified. Research by the Costa Rican Chamber of Commerce suggests that negative family pressure, low self-esteem (particularly related to the tension between women’s professional and traditional roles), and gender stereotypes are the main factors causing minimal representation of women in private-sector leadership. [39] In response to low rates of women’s leadership in the Costa Rican private sector, the government has displayed the images of eight successful Costa Rican women as part of a national publicity campaign to motivate and challenge women to take on leadership positions. Marilyn Batista, who heads the Chamber of Commerce’s program dedicated to the development of women’s entrepreneurship, argues that the campaign helps promote the idea that women’s roles as wives and mothers should not prevent them from taking on high leadership roles. [40] Additionally, 17 companies have already signed the Costa Rican Chamber of Commerce’s 2013 Affirmative Action Agreement for the Promotion of Women’s Leadership in Business. [41] These steps to increase women’s representation at high levels of government and business are encouraging, yet they lack an understanding of gender constructions and are insufficient to address the full scope of barriers constraining women’s leadership in Costa Rica.

Photo source: La República

Moving Forward with Persisting Challenges in Mind

On the whole, the Costa Rican government and non-government actors must seek to better understand the influence of stereotypes on the society’s gendered power dynamics. Similarly, the Costa Rican government should partner with influential individuals in the public and private spheres to spur further discourse on the barriers women face and the importance of gender-equal leadership.

More specifically, legislators need to vigorously support attempts to understand the country’s persisting gender inequality and tackle the institutional factors that confine women’s opportunities. For example, legislators could review the Costa Rican maternity leave system and potentially add paternity leave to help reverse the norm that women are the primary caregivers in society and to help equalize domestic responsibilities across genders. They could also incentivize private companies and organizations to invest in female leadership development by providing financial resources for recruitment, retention, and training.

Unfortunately, even with extensive, enforced quotas, more female politicians in Costa Rica have not been able to change the standard of male leadership, and thus the biases against women during processes of selecting leaders continue. Additionally, the increasingly gender-equal state institutions have not addressed the factors that contribute to women’s challenges in climbing the professional ladder. Steady implementation of quotas has legally institutionalized women’s political representation in government, but the social norms and challenges leadership-seeking women face have not radically changed, preventing substantial gains for women at the higher echelons of the private sector in Costa Rica.

Jessie Durrett, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

1. “Women in National Parliaments.” Inter-Parliamentary Union, February 1, 2013. http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm.

The World’s Women 2010: Trends and Statistics. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2010. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/Worldswomen/WW_full%20report_color.pdf.

2. Kasperkevic, Jana. “These Charts About Women In Leadership Prove How Far The U.S. Is Behind The Rest Of The World.” Business Insider, March 13, 2012. http://www.businessinsider.com/women-worldwide-still-struggle-to-break-into-leadership-roles-2012-3.

3. Franceschet, Susan, Mona Lena Krook, and Jennifer M. Piscopo, eds. The Impact of Gender Quotas. New York: Oxford Universtiy Pess, 2012. 5.

4. Ibid, 4-5.

5. Htun, Mala, and Mark Jones. “Engendering the Right to Participate in Decision-making: Electoral Quotas and Women’s Leadership in Latin America.” In Gender and the Politics of Rights and Democracy in Latin America, 32–56. New York: PALRGAVE, 2002. 35.

6. Ibid.

Franceschet, 8.

7. Htun, 35.

8. Franceschet, 3.

Htun, 35.

9. Htun, 37.

10. Ibid, 39.

11. Franceschet, 5.

“The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” Lima, Peru: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2003. http://www.idea.int/publications/quotas_la/index.cfm. 21.

12. “The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.”

13. Htun, 34,

14. “The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” 20.

15. “Definition of Key Gender Terms.” PeaceWomen, http://www.peacewomen.org/pages/about-1325/key-gender-terms.

16. Sagot, Montserrat. “Does the Political Participation of Women Matter? Democratic Representation, Affirmative Action and Quotas in Costa Rica.” IDS Bulletin 41, no. 5 (September 2010): 25–34. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00163.x. 26.

“The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” 88.

17. Ibid, 89.

18. Ibid, 90.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid, 90.

21. Jones, Mark P. “Quota Legislation and the Election of Women: Learning from the Costa Rican Experience.” The Journal of Politics 66, no. 4 (November 1, 2004): 1203–1223. 1213

22. Jones, 1214.

23. Jones, 1208

“The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” 96.

24. Ibid, 91.

25. Sagot, 26-27.

26. “Costa Rica.” Quota Project: Global Database of Quotas for Women. http://www.quotaproject.org/uid/countryview.cfm?country=54.

27. The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” 92.

28. Jones, 1214.

29. Sagot, 28.

30. The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences.” 94.

31. “Costa Rica.” Quota Project: Global Database of Quotas for Women. http://www.quotaproject.org/uid/countryview.cfm?country=54.

32. Sagot, 29-30

33. Sagot, 30.

34. “Factor F+m Awards.” Costa Rican-American Chamber of Commerce, March 21, 2013. http://www.amcham.co.cr/committees.php?CID=17.

35. “Costa Rica – Escasa Participación de La Mujer En Puestos de Liderazgo.” Women in Management, March 18, 2013. http://www.wim-network.org/2013/03/costa-rica-escasa-participacion-de-la-mujer-en-puestos-de-liderazgo/.

36. Hausmann, Ricardo, Laura D. Tyson, and Saadia Zahida. The Global Gender Gap Report 2012. World Economic Forum, 2012. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GenderGap_Report_2012.pdf.

37. “Factor F+m Awards.”

38. Ibid.

39. “Costa Rica – Escasa Participación de La Mujer En Puestos de Liderazgo.” Women in Management, March 18, 2013. http://www.wim-network.org/2013/03/costa-rica-escasa-participacion-de-la-mujer-en-puestos-de-liderazgo/.

40. Rodriguez, Andrea. “Campaña Busca Impulsar Liderazgo de La Mujer En Puestos de Gerencia.” La Nación, June 13, 2013, sec. Economía. http://www.nacion.com/economia/Campana-impulsar-liderazgo-puestos-gerencia_0_1347465552.html.

41. Lizeth, Brenda. “Impulsa Cámara de Comercio de Costa Rica Liderazgo de Mujeres.” Monterrey Times, March 6, 2013. http://monterreytimes.com.mx/archivos/36086.