No Longer Activa e Altiva: Brazil’s Foreign Policy Stumbles under Temer

By Maria Rodriguez-Dominguez, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

Over a decade ago, the world witnessed the emergence of a relentless rising power. As a result of an effective and carefully implemented foreign policy, the South American giant and fifth largest country in the world quickly consolidated itself as regional leader par excellence and was joining efforts with other nations to shift the global balance of power. This trend may have been less energetic during President Dilma Rousseff’s mandate, but the Brazilian foreign policy post-coup is merely a shadow of its former self. Additionally, the post-ideology stance of the new government is far from being genuine as its diplomacy encompasses a neoliberal view that favors an alignment with the United States over regional integration, and South-South cooperation.

Brazilian Diplomacy under Lula and Dilma

Luiz Felipe Lampreia, Minister of Foreign Affairs under President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, once declared that “o Brasil não pode ser mais do que é” (Brazil cannot pretend to be something more than it is).[i] Lula’s foreign policy, carefully articulated by Celso Amorim (Minister of Foreign Affairs), Marco Aurélio Garcia (Special Advisor) and Samuel Pinheiro Guimaraes (Secretary General of Foreign Affairs) demonstrated that a “diplomacia activa e altiva (active and prominent diplomacy), could serve to consolidate Brazil’s regional and international influence. In addition to observing historical principles of Brazilian diplomacy, such as non-intervention and self-determination, the quartet embraced new precepts, such as non-indifference and emphasized regional integration and decentralization of global power through the promotion of multilateralism and South-South cooperation.[ii] [iii]

Although the country’s agenda prioritized regional integration through the Southern Cone Market (Mercosur), Lula’s foreign policy was successful in strengthening bilateral relations with other Latin American nations, regardless of the governments’ political orientation.[iv] For example, Brazil acted as a credible interlocutor with both the opposition as well as the government during the Venezuelan crisis in 2003 and backed the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) as an important mediator vis-à-vis the regional political crises and the Andean diplomatic crisis in 2008, just as it did in the Honduran Coup in 2009.

Similarly, Brazilian foreign policy was consolidated as an effective instrument to advance the country’s interests and to shift the balance of power through multilateralism. Despite its profound shortcomings, Brazil’s leadership in the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) represented the nation’s largest engagement in peacekeeping operations to date. Together with other regional powers and developing countries, Brazil strongly advocated for the reform of the United Nations Security Council to expand the number of permanent and non-permanent members in an effort to more accurately reflect current political realities.[v] For more than a decade, Brazil actively engaged with other so-called BRICS countries (a group of emerging markets made up of China, Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa), to call for new initiatives such as the BRICS Development Bank, and even moved to diversifying its trade strategies to reduce its dependence with the United States. As a result, China became Brazil’s largest trading partner in 2009.[vi]

Despite the move away from its traditional U.S.-trade centrism and the opposing views concerning international trade, the governments of Lula and Dilma maintained an amicable relationship with Washington. Negotiations on ethanol production, as well as efforts to resolve trade disputes through the mechanisms of the World Trade Organization (WTO), are a few examples of the cooperation that defined the bilateral relationship.[vii] The economic results of this active foreign policy were positive for Brazil and included a surplus of $308 billion USD as of 2014, and a global trade participation rate of 1.46%.[viii] Reaffirming Brazil’s sovereignty, Dilma cancelled a visit to the United States in 2013 over alleged spying revelations. However, both governments went on to re-establish a fruitful relationship that eventually facilitated Dilma’s visit two years later.[ix]

More concerned about the domestic economic slowdown, Dilma Rousseff may not have emphasized foreign policy as much as her predecessor. However, her administration was able to achieve key diplomatic victories through the appointment of José Graziano da Silva, the architect of the laurate Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) program, as Head of the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2011 and Roberto Azevêdo as Director General of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2013.

The End of Ideology in Brazil’s Foreign Policy?

Despite the positive record of Brazilian diplomacy over 13 years, the government of Michel Temer announced a reorientation toward a so-called “non-ideological” diplomacy much more focused on trade.[x] According to Aloysio Nunes Ferreira, the current Minister of Foreign Affairs, the goals of the new foreign policy are defense of national interests and engagement with the rest of the world.[xi] For anyone with an understanding of the foreign policy carried out by the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) governments, these assumptions seem redundant as both objectives were largely achieved by Lula’s and Dilma’s administrations.

Both Nunes Ferreira and José Serra, the previous Minister of Foreign Affairs, have accused PT foreign policy as being too ideological. However, they conveniently disregard the fact their current foreign policy is based on a neoliberal ideology which highly favors the business groups that keep the Temer government in power.

As opposed to all of the foreign ministers under Lula and Dilma, who were career diplomats, Serra and Nunes were long-time politicians from the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Brazilian Social Democracy Party, PSDB). Moreover, the fact that both of them have been included in the Lava Jato (Car Wash) Operation, suspected of corruption charges, puts into question the so-called pragmatism that they preach. To indicate the severity of events, in 2015 for example, the Brazilian Supreme Federal Court authorized the investigation of Nunes Ferreira for bribery during his campaign for the Senate in 2010.[xii]

By accusing the PT diplomacy of ideological, Temer’s government is hypocritical because it is forgetting the fact that its foreign policy is based on a market ideology that seeks to preserve the former status quo which was strongly aligned with U.S. interests. It is no coincidence that on his first trip abroad to India and Japan, Temer was accompanied by Blairo Maggi, the Minister of Agriculture, also known as the “Soy King,” who has been accused of being one of the biggest deforesters of the Amazon rainforest.[xiii]

The reorientation of Brazilian foreign policy has been especially visible at the regional level, particularly with regard to the role sought by Mercosur and Unasur. As opposed to the previous integration efforts, Temer’s first action was to block, together with Argentina, Uruguay from passing Mercosur’s presidency pro-tempore to Venezuela. Venezuela was finally able to preside over the regional organization, as Uruguay insisted at the time on respecting the organization’s rules regarding succession of the presidency.[xiv] This overt attack against the Andean country negatively affected Brazil’s regional leadership, as it lost its ability to act as mediator in the Venezuelan crisis as it had in 2003. Additionally, Temer has favored the Organization of American States (OAS) as the main conflict resolution organ, disregarding the previous role of Unasur to effectively solving political crises within the region.[xv] This is problematic because it reveals a growing realignment with the United States as opposed to Unasur’s regional independence.

As Brazil’s involvement with the BRICS is weakening, Temer’s government has ardently sought alignment with the United States. For instance, Nunes Ferreira recently revealed the administration’s intention to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement rather than through Mercosur, arguing that “the two largest countries in the Americas share a great deal in common… and should work together to build a mutually beneficial agenda.”[xvi] To further advance such an agenda, the government has approved measures that directly favor U.S. interests, such as the end of the compulsory participation of the state-run company Petrobras in the exploration of oil in the Pré-Sal reserve. There is also a bill that would allow foreign governments to use the Alcântara launch base in the State of Maranhão.[xvii] Brazil has also renounced its intention of reforming the U.N. Security Council, which José Serra wrote off as “a fight for the big guys.”[xviii]

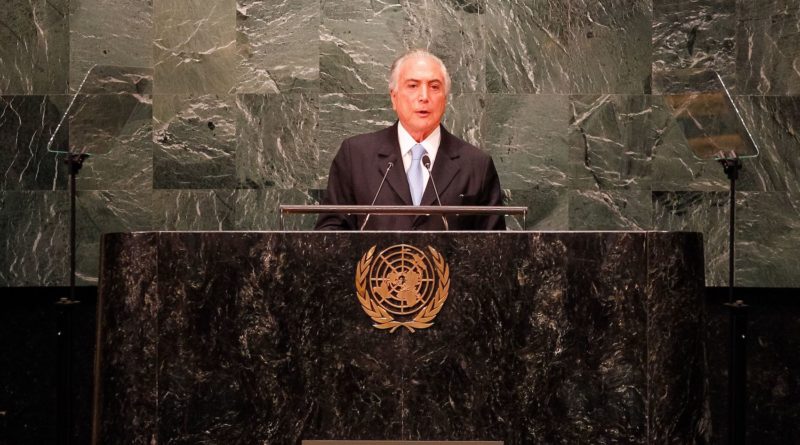

This shift toward a more submissive foreign policy was criticized by David Rothkopk, former editor of Foreign Policy magazine in an interview with the BBC in May 2016, who declared, “if Serra thinks that reforming foreign policy means to undo what Lula has done, he is not acting in the best interests of Brazil”.[xix] According to Rothkopk, establishing trade policies with only certain countries, keeping a low profile in multilateral relations, and adopting a “skeptical-reflexive” tone with the United States will not be positive for Brazil.[xx]Indeed, after more than a year in power, Temer and his two foreign ministers have shown that neither sovereignty nor the promotion of multilateralism is an essential component of their administration’s diplomacy. Moreover, Temer’s controversial takeover and his suspected involvement in corruption episodes have taken a negative toll on Brazil’s reputation at the international level. Several foreign leaders such as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. Vice President Mike Pence have opted not to visit the country and Temer’s team has had a hard time setting bilateral meetings in international fora such as the G20 meeting in Germany and the most recent session of the U.N. General Assembly.[xxi]

For years, Brazilian diplomacy was a global example of a dignified and active foreign policy that, along with a group of emergent economies, had the potential to shift the balance of power toward a multipolar world order. Its leadership allowed it to act as a credible mediator within the region while maintaining solid bilateral relationships with an array of governments, regardless of their political orientation. Brazil was also able to advance its national interests through diplomatic initiatives. Despite this exemplary reputation, Temer’s government has disdainfully labeled the previous foreign policy as ideological. That said, it is contradictory that a government that has shamelessly favored the interests of a nefarious group which has kept it in power, can implement an impartial and independent foreign policy. Its current alignment with the United States and its rejection of multilateralism signals that Brazil’s diplomacy is far from being non-ideological. However, as former Foreign Minister Celso Amorim stated: “When policy is carried by the left, it is seen as partisan. When the right carries it, it is perceived as state policy. Perhaps this is because the right has always dominated the state.”[xxii]

By Maria Rodriguez-Dominguez, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Aline Piva, Assistant Deputy Director and Head of Brazil Unit, and Liliana Muscarella Research Fellow

Image: Michael Temer at United Nations Taken From: Wikimedia

[i] Roberto Amaral. “Serra e o servilismo na política externa.” Carta Capital. July 08, 2016. https://www.cartacapital.com.br/internacional/serra-e-o-servilismo-na-politica-externa.

[ii] João Paulo Caldeira. “Lula e Dilma não implantaram diplomacia ‘ideológica’, diz Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães.” GGN. July 04, 2016. https://jornalggn.com.br/noticia/lula-e-dilma-nao-implantaram-diplomacia-ideologica-diz-samuel-pinheiro-guimaraes.

[iii] Amorim, Celso. “A política externa do governo Lula: dois anos.” Ministério das Relações Exteriores. http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/pt-BR/discursos-artigos-e-entrevistas-categoria/7788-a-politica-externa-do-governo-lula-dois-anos-artigo-do-ministro-das-relacoes-exteriores-embaixador-celso-amorim-publicado-na-revista-plenarium.

[iv] João Paulo Caldeira. Op. Cit.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] “Brazil sets trade records, due to Chinese demand.” NPR. January 02, 2012. http://www.npr.org/2012/01/02/144587105/brazil-sets-trade-records-due-to-chinese-demand.

[vii] João Paulo Caldeira. Op. Cit.

[viii] Marcelo Zero. “Nem o barão do Rio Branco salvaria a política externa do golpe.” 247. March 6, 2017. https://www.brasil247.com/pt/colunistas/marcelozero/283605/Nem-o-bar%C3%A3o-do-Rio-Branco-salvaria-a-pol%C3%ADtica-externa-do-golpe.htm

[ix] Dan Roberts. “Brazilian president’s visit to US will not include apology from Obama for spying.” The Guardian, June 30, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/30/brazil-dilma-rousseff-obama-nsa-spying-apology.

[x] Aloysio Nunes Ferreira. “Brazil’s Foreign Policy Is “Back in the Game”.” Americas Quarterly. April 17, 2017. http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/brazils-foreign-policy-back-game.

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Diogo Bueno and José Medeiros. “Aloysio Nunes: uma política externa omissa e submissa.” Carta Capital. March 03, 2017. https://www.cartacapital.com.br/blogs/blog-do-grri/aloysio-nunes-uma-politica-externa-omissa-e-submissa.

[xiii] João Filho. “Gaffes, mistakes, and humiliations define Brazil’s new foreign policy.” The Intercept. October 26, 2016. https://theintercept.com/2016/10/26/gaffes-mistakes-and-humiliations-define-brazils-new-foreign-policy/.

[xiv] Roberto Amaral, op. cit.

[xv] Gilberto M.A. Rodrigues. “Brazil’s Foreign Policy: A Regressive Path?” Aula Blog. September 06, 2017. https://aulablog.net/2017/09/06/brazils-foreign-policy-a-regressive-path/.

[xvi] Aloysio Nunes Ferreira, Op. Cit.

[xvii] Esteban Actis. “La política exterior de Michel Temer.” Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica. August 31, 2017. http://revistafal.com/la-politica-exterior-de-michel-temer/.

[xviii] João Filho. Op. Cit.

[xix] Ibid

[xx] Ibid

[xxi] Ricardo Senra. “Após críticas internacionais, Temer defende proteção à Amazônia em discurso na ONU.” BBC Brasil. September 19, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-41318365.

[xxii] Fernando Caulyt. “”Há contradições em novas diretrizes do Itamaraty”, diz Celso Amorim.” DW. June 14, 2016. http://www.dw.com/pt-br/h%C3%A1-contradi%C3%A7%C3%B5es-em-novas-diretrizes-do-itamaraty-diz-celso-amorim/a-19328437.