No Justice: The U.N.’s Refusal to Compensate Cholera Victims in Haiti

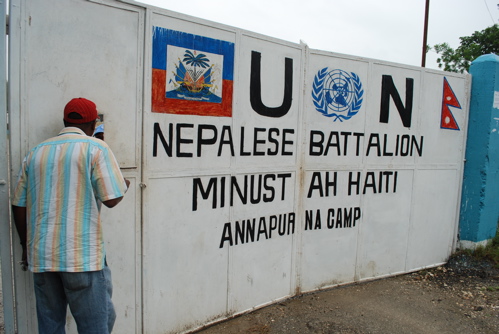

Immediately following the devastating earthquake that struck Haiti on January 12, 2010, which caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands and the resulting homelessness of millions, another tragedy ensued. Nearly 650,000 Haitians contracted cholera, a potentially fatal waterborne disease that had never before been known to exist in the country. [1] After much research was conducted, it was discovered that the disease was all but certainly brought to Haiti by Nepalese peacekeeping troops, who were serving in the U.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH).

The Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), a Boston-based NGO, has filed a lawsuit against the United Nations for compensation on behalf of nearly 5,000 of the 650,000 Haitians who have suffered from cholera. The organization’s failure to take responsibility for its clear involvement in the introduction and the rampant transmission of cholera in an effort to protect its reputation in Haiti and abroad not only diminishes its credibility in the eyes of the international community, but also represents a clear violation of the human rights of hundreds of thousands of cholera-stricken Haitians. [2]

Cholera Strikes and Leaves a Deadly Wake

After an extensive three-week investigation in November 2010 by a team of French epidemiologists headed by Dr. Renaud Piarroux, a professor at Université de la Méditerranée in Marseille who is an expert in cholera, it was concluded that the strain was likely transferred to Haiti through peacekeepers from Nepal, the site of a severe cholera outbreak in late 2010. [3] These peacekeepers practiced very poor waste management at their base near Mirebalais, a town approximately 40 miles northeast of Port-au-Prince. [4] Sewage seeped into the nearby Artibonite River, which provides many Haitians with drinking water, bathing grounds, and irrigation. [5] Due to the Nepalese soldiers’ haphazard waste management policies, it was always suspected by many experts that their base was the original source of contamination.

As waste continued to be released into the river, cholera spread to waterways throughout the country. [6] To make matters worse, because the disease has had no historical presence in Haiti, the Haitian people had virtually no immunity to the disease. [7] People from the town of Mirebalais near the base were the first to develop symptoms similar to those associated with cholera, such as severe dehydration, diarrhea, and vomiting. [8] Still recovering from the earthquake in January 2010, the Haitian government did not have the resources to fight a pandemic such as cholera without international aid. [9] Ironically, the very people on a mission to provide aid to the Haitian people were directly responsible for much of their suffering.

The results of the investigation by the French doctors are indisputable. Microscopic analysis proves that the strain of cholera in Haiti is almost identical to the strain that was found in Kathmandu, Nepal. Furthermore, the team concluded that the cholera was clearly imported from another nation, because it originated “in the center of the country, not by the sea, nor in the refugee camps.” [10]

Despite this overwhelming preponderance of evidence, the United Nations distanced itself from the allegations that it was ultimately responsible for introducing cholera to Haiti. It defended the Nepalese soldiers, insisting that their handling of sewage complied with U.N. standards and regulations. However, the Associated Press reported that the Nepalese troops were disposing of their waste in pits located uphill from a stream in which locals frequently bathed. [11] Furthermore, Al Jazeera filmed Nepalese troops working rapidly to cover up evidence of their lax handling of sewage prior to the arrival of inspectors. [12] Despite efforts to distance itself from responsibility for the outbreak, most experts agree that the United Nations bears full responsibility for the importation of cholera to the region.

Why the Lawsuit?

In November 2011, approximately one year after the cholera outbreak, the IJDH decided to sue the United Nations for compensation on behalf of the victims and their families. [13] The United Nations, however, maintained the position that it was not responsible for the outbreak. The IJDH specifically argues that the victims should be compensated for the poor health screenings implemented by the United Nations prior to the peacekeepers’ departure to Haiti, as well as the inadequate waste management system utilized by Nepalese troops at the base in Mirebalais. [14] Further demands of the IJDH for the United Nations include compensation for the victims and their family members, the implementation of a water and waste management system to contain the cholera outbreak, and a public apology from U.N. officials for the agency’s role in the epidemic. [15]

Although U.N. authorities had knowledge of the current outbreak of cholera in Nepal, they did not take necessary precautions when screening the troops prior to departure. [16] A majority of the troops were not tested for cholera, and the United Nations even permitted troops who were tested to travel for 10 days prior to their deployment to Haiti, providing a wide window of opportunity for the contraction of cholera.[17] These lax pre-departure health procedures combined with the inadequate waste management at the Mirebalais base created an ideal environment in which cholera could easily be contracted and then transmitted.

According to the IJDH, the United Nations should be held accountable for its troops’ poor sanitation practices. After the aforementioned investigations were carried out, it seemed clear that the Nepalese peacekeepers disregarded international standards on waste management while on mission and utilized a sewage system ridden with broken pipes and manually dug open pits. [18] The Nepalese soldiers most certainly were aware that the transmission of cholera could be a significant health concern, yet they created a system that was irresponsible by any international standard.

Response of the United Nations

The United Nations has taken a number of steps to protect its reputation and maintain its credibility in response to these allegations of wrongdoing in Haiti. The international body conducted its own independent panel to trace the source of the cholera strain encountered in Haiti. Unsurprisingly, its results were far different than those of Dr. Piarroux and his team. The U.N. panel in charge of investigating the cholera epidemic conveniently concluded that the original source of the strain was unidentifiable and that the cause of the outbreak was due to a “confluence of circumstances.” [19] However, the fact that the panel was appointed by Ban Ki-moon, the U.N. Secretary-General, suggests that these findings are not fully impartial. [2o] It seems more likely that Ban, committed to protecting the reputation of the United Nations, designated these panel positions to individuals he believed would produce a report favorable to the international body.

When the IJDH’s suit came about, the United Nations claimed that it had legal immunity from the damages. A section of the 1946 United Nations Convention on Privileges and Immunities affords the United Nations the right to have legal protections for itself and its workers in the nations in which it is operating. [21] To complement this immunity, however, the United Nations also requires that a Standing Claims Commission be created in the event that individuals require compensation from activities directly related to the presence of the United Nations. [22] Unfortunately, no Standing Committee has previously been established since the creation of the United Nations because the agency regularly, and conveniently, has fallen back on its immunity provision. Assuming that this case will not set a major precedent, it is unlikely that a Standing Committee will be established, or that the victims will ever be compensated for their suffering. [23]

The United Nations’ claim of immunity has caused controversy because of the abundance of scientific evidence supporting the claim that its peacekeepers were the original source of contamination. Many feel as if this action on behalf of the United Nations contradicts its platform of the promotion of human rights and the protection of civilians—the very elements on which the organization was originally founded upon in 1945. The United Nations was also created to prevent wrongful acts of death. However, in this situation, the organization was found to be the perpetrator of such acts. The United Nations’ lack of acknowledgement of its role in the outbreak has forever damaged its credibility in the eyes of many in both Haiti and the international community.

What’s Next for Justice and a Healthier Haiti

The cholera outbreak in Haiti also demonstrates that further debate and analysis is necessary regarding the role of peacekeeping missions. Rather than protecting those stricken by cholera in Haiti, the United Nations has attempted to distance itself from the outbreak, proving that its concern for its reputation and credibility is greater than its concern for the health of over 650,000 victims, of which 8,000 have lost their lives to the cholera epidemic. [24]

Though it is unlikely that the United Nations will be held legally accountable, it will forever be held accountable by the people of Haiti. Considering MINUSTAH’s controversial origins, which date back to the 2004 overthrow of President Jean Bertrand Aristide, it is unsurprising that the Haitian population has come to regard the United Nations and international NGOs with distrust. The cholera outbreak in Haiti only validates this skepticism. Haiti does not have the resources to combat the cholera epidemic, which experts say could potentially last a decade. [25]

Rather than dedicating vast resources to preventing the transmission of the cholera epidemic, the United Nations has selfishly opted to protect its reputation, leaving many Haitians to suffer even more than they were in the months immediately following the 2010 earthquake. The Haitian people, already struggling to survive on a day-to-day basis, deserve compensation for this devastating catastrophe that has already taken the lives of thousands, and could potentially destroy the lives of many more victims in Haiti and beyond.

Christie Mount, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

[1] Sarah Dehm, “Cholera in Haiti: Is UN Immunity Now Impunity?” The Interpreter, 21 June 2013, http://www.lowyinterpreter.org/post/2013/06/21/UN-immunity-as-impunity-Seeking-redress-for-Haitian-cholera-victims.aspx.

[2] Rashmee Roshan Lall and Ed Pilkington, “UN Will Not Compensate Haiti Cholera Victims, Ban Ki-moon Tells President, The Guardian, 21 February 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/21/un-haiti-cholera-victims-rejects-compensation.

[3] Anastasia Moloney, “Haiti Cholera Victims Deserve Better from U.N.-Rights Group,” Trust.org, 10 July 2013, http://www.trust.org/item/20130710104532-0qy6b; Renaud Piarroux, “Mission Report on Cholera Epidemic in Haiti by Professor Renaud Piarroux,” UCLA Department of Epidemiology School of Public Health, http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/cholera_haiti_piarrouxreport.html.

[4] Lall and Pilkington, “UN Will Not Compensate.”

[5] Dehm, “Cholera in Haiti.”

[6] Jonathan M. Katz, “In the Time of Cholera,” Foreign Policy Magazine, 10 January 2013, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/01/10/in_the_time_of_cholera.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Haiti’s Earthquake Death Toll Revised to at Least 250,000,” The Telegraph, 22 April 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/haiti/7621756/Haitis-earthquake-death-toll-revised-to-at-least-250000.html.

[10] “Haiti Cholera Outbreak: Nepal Troops Not Tested,” BBC News, 8 December 2010, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-11949181.

[11] Katz, “In the Time of Cholera.”

[12] Deborah Sontag, “In Haiti, Global Failures on a Cholera Epidemic,” New York Times, 31 March 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/01/world/americas/haitis-cholera-outraced-the-experts-and-tainted-the-un.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&.

[13] Dehm, “Cholera in Haiti.”

[14] Ibid.

[15] Lall and Pilkington, “UN Will Not Compensate.”

[16] Dehm, “Cholera in Haiti.”

[17] Lauren Carasik, “The United Nations’ Role in Haiti Cholera Outbreak,” Al Jazeera, 20 December 2012, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/11/20121115101554961482.html.

[18] Katz, “In the Time of Cholera.”

[19] Lall and Pilkington, “UN Will Not Compensate.”

[20] Moloney, “Haiti Cholera Victims.”

[21] Armin Rosen, “How the U.S. Caused Haiti’s Cholera Crisis – and Won’t Be Held Responsible,” The Atlantic, 26 February 2013, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/02/how-the-un-caused-haitis-cholera-crisis-and-wont-be-held-responsible/273526/.

[22] Dehm, “Cholera in Haiti.”

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.