More Pragmatic, Less Ideological: Bringing the U.S. and Bolivia Together?

By: W. Alejandro Sanchez, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Relations between the U.S. and Bolivia have been more or less tense for close to a decade, but now the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) may be the catalyst for bringing La Paz and Washington together. This can be surmised from the January declarations by senior Bolivian government official that La Paz is open to re-start information sharing with the DEA. The goal of this potential partnership would be to crack down on drug trafficking in the landlocked country, which is becoming problematic due to domestic cocaine production as well as cocaine shipments arriving from Peru into the country.

It remains to be seen if bilateral relations are likely to improve in the near future. Should this proposal for intelligence information progress, it could provide the momentum needed for the two governments once again exchanging ambassadors or, at the very least, there could be a good-will meeting between President Barack Obama and President Evo Morales in the upcoming Summit of the Americas. For the time being, it seems that the two governments are starting to take gradual steps to increase cooperation against a common enemy: drug trafficking.

The 2008 Incident

U.S.-Bolivia relations became tense ever since President Morales’ rise to power in 2006. Noteworthy, Morales was the first ever indigenous Bolivian to become head of state. Unfortunately for Washington, Morales did not hold the U.S. government in high regard due to the dark history of U.S. intervention in his country and the rest of Latin America. Additionally, the Bolivian head of state was a close ally of the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who survived a short-lived coup in April 2002.

Due to some of these precedents, Morales likely viewed Washington’s presence in Bolivia with suspicion. In 2008, the situation took a turn for the worst. The Bolivian government expelled the U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia, Philip Goldberg, after accusing him of fomenting internal unrest as he had met with Bolivian opposition leaders, specifically, with Ruben Costas, tgovernor of Santa Cruz. “Without fear of the empire, I declare Mr. Goldberg, the US ambassador, ‘persona non grata,’ … He is conspiring against democracy and seeking the division of Bolivia,” Morales memorably declared.[i] At the time, President Morales certainly had reason to believe that a foreign power was trying to undermine him as major protests rocked Bolivia in 2008, leading to several departments, including Santa Cruz (led by the aforementioned Costas), pursued secession.

Washington replied in similar fashion shortly after the Bolivian president’s decision. “In response to unwarranted actions and in accordance with the Vienna Convention (on diplomatic protocol), we have officially informed the government of Bolivia of our decision to declare Ambassador Gustavo Guzman persona non grata,” State Department spokesman Sean McCormack said then.[ii] Since, the two countries have not exchanged ambassadors.

Currently, the highest-level official in the Bolivian embassy in the U.S. is the chief of mission, retired General Freddy Bersatti, a former commander of the Bolivian Army.[iii] Meanwhile, the highest-ranking officer in Washington’s embassy in La Paz is the Charge d’Affaires, Peter Brenan, who was the former Minister-Counselor for Communications and Public Affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan.[iv]

Bolivia-U.S. Relations: 2008-Present

Apart from the lack of ambassadors, there have been a number of other decisions that have affected bilateral relations. For example, apart from expelling Ambassador Goldberg, in 2008, President Morales also ejected the DEA from operating in Bolivia. More recently, in 2013, the Bolivian head of state threatened to close the U.S. embassy in Bolivia. The reason for this decision was a bizarre incident in which his presidential plane was forced to land in Austria as he was flying back from Russia, where he attended a Summit.[v] Apparently, the U.S. allegedly influenced several European governments to deny the Bolivian presidential jet from entering their air-space because it was believed that NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden may have been hiding in the plane after President Morales had declared that he was considering giving Snowden asylum.

While the Bolivian government ultimately did not shut down the U.S embassy, in 2013 it did expel USAID for “conspiring” against the Bolivian government and population. It is unclear if there was a specific incident that triggered this decision, though President Morales declared that USAID was fomenting peasant communities and unions to rise up against his government.[vi]

USAID denounced the decision by La Paz in a statement that said, since 1964 “[USAID] has strived to help the Bolivian government improve the lives of ordinary Bolivians. All USAID programs have been supportive of the Bolivian government’s National Development Plan, and have been fully coordinated with appropriate government agencies.”[vii] While USAID did have positive initiatives in the landlocked nation, these projects did not protect it from President Morales’ decision.

Nevertheless, in spite of the aforementioned incidents, the two countries have tried to “reset” relations – namely, in 2011 La Paz and Washington signed an agreement to reestablish relations.[viii] Despite the State Department supporting the agreement, little has happened since, and relations even slightly worsened in 2013 with USAID’s expulsion.

In other words, bilateral relations between La Paz and Washington have been tense for almost a decade, regardless of there being a Republican or Democrat in the White House. Meanwhile, President Morales was comfortably re-elected for a new presidential term this past October 2014, obtaining 61% of the vote, 37 points more than his closest challenger, Samuel Doria Medina.[ix] President Morales seems to have a firm hold on power for the foreseeable future. (Moreover after the 2014 elections, his political party, the Movimiento al Socialismo, has a strong control of both the Senate and Deputy Chamber).

Finally, it is important to mention that as tense as diplomatic relations may be, Washington-La Paz trade has actually flourished. Trade between the two countries reached $1.7 billion USD in 2014, three times more than in 2009. The major goods that the U.S. imports are gold and quinoa. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that some of the gold being sold is actually Peruvian, which is smuggled across the Peruvian-Bolivian border and then sold as if it had been extracted in Bolivia[x]. Additionally, the U.S. suspended Bolivia’s membership to the Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Act (ATPDEA) in 2008, which gave preferential treatment to Bolivian exports to the U.S., such as textiles.[xi] Hence, while bilateral trade is growing, there are outstanding factors that must be taken into account to understand which sectors of Bolivian society are benefiting from it.

The DEA Opening and Future of U.S.-Bolivian Relations

While lacking positive developments between La Paz and Washington in recent years, the fact that the DEA could once again provide aid to Bolivian security agencies is a positive, even important, development.

In late January, Bolivian Minister of Interior Hugo Moldiz declared that his government was open to improving security relations with Washington.[xii] During an interview with the TV show “Levantate Bolivia,” aired by the Bolivian channel Cadena A, Moldiz declared “we have to move to another stage [of bilateral relations] What does this imply? We will exchange information, there is no need for the DEA to return to this country, but that does not mean, for example, that we cannot exchange [intelligence] information with other countries [and with] the DEA.”[xiii]

Because of this ample room for improvement, it will be important to monitor the upcoming Summit of the Americas that will take place next month in Panama. Currently, all eyes are on whether the Cuban government will be able to participate in the forum, as the U.S. government has historically wielded a veto against Havana from attending.[xiv] Nevertheless, there will be plenty of sideline meetings between the attending heads of state and their delegations on that occasion. Case in point, it will be important to observe if President Obama and President Morales will meet while they are in Panama City and if the two leaders will discuss exchanging ambassadors or, at least, a renewed role for the DEA in Bolivia.

Analysis

Thus, the question may be: what has prompted President Morales to consider opening up to Washington and the DEA at this time? First of all, it is important to clarify that President Morales can be regarded as a pragmatist, and while his ideological convictions are strong, as is his distrust of the U.S., some kind of accommodation can be reached so that La Paz can receive the international support it needs to crack down on drug international trafficking.[xv]

Despite Morale’s significantly high-levels of popularity, this does not imply that the situation in the Andean nation is ideal. Internal security and drug trafficking remain major sources of concern to the Bolivian leadership, particularly as Bolivia is the third largest producer of cocaine in the world. During his time in power, President Morales has supported an increase of coca production, as it is a plant that has ties to the Andean region since pre-Inca times. The problem is that significant portions of coca production in Bolivia end up being transformed into cocaine. According to Minister Moldiz, Bolivia produced some 22 thousand hectares of coca in 2014, out of which 19 thousand was produced legally.[xvi] According to a 2013 report, Bolivian drug traffickers are able to produce 1 kilogram of cocaine from 317 kilograms (700 pounds) of coca leaves.[xvii]

Some examples of recent drug busts are necessary to illustrate the significant amounts of cocaine being produced. In October 2013, the Bolivian police discovered six mobile-production units of cocaine in Apolo, a coca-growing area north of La Paz.[xviii] More recently, in December 2014, the Bolivian police seized 408 kilograms of cocaine and one narco-plane in three separate operations. In just one operation in the Santa Cruz department, the Bolivian police seized the plane and 327 kilograms inside it when the pilots fled the aircraft in motorcycles.[xix] According to Bolivian police, the various Bolivian security agencies seized 1.8 million doses of cocaine in 2014.[xx]

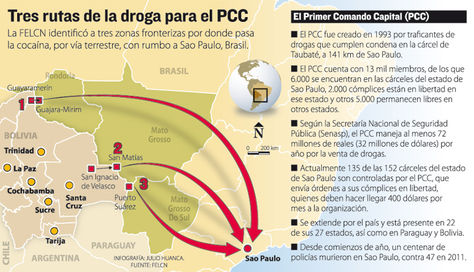

Moreover, the problem is not just Bolivia’s domestic production of cocaine, but also cocaine smuggling from neighboring Peru. There is currently a veritable “narco air bridge” in which drug traffickers are smuggling cocaine from Peru into Bolivia, profiting from the isolated border areas that both governments cannot fully monitor.[xxi]

The recent drug busts in Bolivia can be interpreted in different ways. First, Bolivian security agencies are increasingly effective at cracking down on drug trafficking; or second, there is an increasing production and trafficking of cocaine in Bolivia, which has led to increased drug seizures, but plenty of others still go undetected.

This is not to say that the Bolivian government has been unable to combat drug trafficking; Bolivian security forces are cracking down on criminals. Moreover, in recent years the Bolivian government has acquired helicopters to act as the workhorse and cornerstone of the security forces’ anti-drug trafficking strategy. Given that the regions in which drug traffickers operate are isolated, helicopters are necessary to deploy troops. Hence, from this perspective it is a positive sign that La Paz has purchased Z-9 helicopters from China and Super Puma helicopters from Airbus, headquartered in France.[xxii]

So far it seems that the Bolivian police is the spearhead of the country’s operations against drug trafficking. This brings up the obvious concern that police officers could become entangled in drug trafficking operations, as has been the case in Mexico, to make a quick dollar (or boliviano). In an interview with COHA, Theo Roncken from the Accion Andina-Bolivia initiative argued that he hopes that the Bolivian military will stay away from carrying out these operations so that it will not become as “contaminated” as the country’s police forces. (At the time of this writing, the former commander of the police, Oscar Nina, has been accused of being, along with his family, involved in drug trafficking).

Ramifications

One obvious question about Minister Moldiz’s comments is: why now? In other words, it is important to discuss whether there have been some circumstances that have influenced the Bolivian government into making these candid declarations regarding the renewal of negotiations with the DEA. For the sake of providing a comprehensive analysis, speculation about internal and external factors is pivotal

First of all, there could always be the possibility that sectors within the Bolivian government seek a closer rapprochement with Washington, or at least the DEA. Certainly, the Bolivian security forces could profit greatly from DEA intelligence in order to crack down on internal drug trafficking and to understand regional developments (i.e. criminal initiatives around Bolivia’s neighbors, such as Brazil and Peru). One could speculate whether drug trafficking in Bolivia has become a more serious problem than what is being reported through the country’s media. La Paz may be under pressure to obtain external support to achieve greater successes. Nevertheless, in off-the-record discussions with COHA, an expert on Bolivia explained that the Seis Federaciones del Trópico de Cochabamba, a group of coca-growing unions from La Paz and Cochabamba, are against the DEA operating in their area to crack down on illegal coca-growing.[xxiii] President Morales happens to also be the president of this amalgamation of federations. He will have to walk a fine line between obtaining foreign intelligence to combat drug trafficking without alienating some of his supporters.

There are also geopolitical events that could explain Bolivia’s decision. Namely, just this past December, Washington and Havana jumpstarted a new initiative to improve relations between the two countries. Meanwhile, Venezuela’s economy remains in crisis and popular protests continue. The Bolivian government could have realized that since its closest allies are either in internal turmoil or potentially increasing their ties with the U.S., it would make sense for a change of course and renew ties with Washington. Then again, some are skeptical as to how much relations will improve. In an interview with COHA, Jim Shultz, director of the Democracy Center in Cochabamba, explains that “Bolivia and the US have been talking about restored diplomatic relations for years and never seem to get to the end game.”

President Morales was never as ideological as President Chavez or other members of the Bolivarian movement. If anything, Morales has always been more of a pragmatist when it comes to both domestic and foreign policy. In an interview with COHA, Professor Kevin Healy from George Washington University explains that as early as Morales’ second presidential term, we have seen him move away from some of his more center-leftist domestic initiatives. Thus, it is perfectly logical to assume that the Bolivian government may decide to take a more realist approach towards its relations with foreign powers, such as collaborating the DEA against a common threat. This does not mean that we will see DEA agents in Bolivia in the near future, as Minister Moldiz declared that he was against this and Morales would probably assume that the U.S. agency may try to overthrow him. Nevertheless, there is ample room for short- or medium-term initiatives between the DEA and La Paz that can be mutually beneficial. Professor Healy argues that accepting DEA intelligence, should this happen, does not mean that the Bolivian government is compromising on its ideals.

Moreover, there is the question of whether new DEA-provided intelligence information will affect the Bolivian government’s ongoing initiatives against drug trafficking. The aforementioned Mr. Roncken from Accion Andina-Bolivia argues that his main concern is that “intelligence information, instead of helping provide solutions, could end up supporting discretionary policies” which targets some aspects of drug trafficking but does not address others. For example, the Bolivian government will probably want to avoid targeting illegal coca crops in Chapare and Cochabamba, given that the president receives significant backing from the coca unions in that regions.

Geopolitical Losers?

Finally, there is the question of whether there are any losers from a possible La Paz-DEA rapprochement as extra-hemispheric powers like the Russia and China have profited from growing anti-Washington governments in Latin America. Hence, should Bolivia and Washington begin to improve ties once again, this could isolate those governments from South America.

As for a “great power politics” approach at a potential La Paz-DEA deal, if it ever occurs, this should not be regarded as a “win-lose” situation for countries like Moscow or Beijing. Morales will probably want to continue his relations with all of these nations via various projects (i.e. China’s sale of military helicopters to Bolivia or Russia’s Gazprom searching for natural gas there), but DEA intelligence information could provide his security forces with an advantage in combating drug trafficking that the aforementioned countries cannot.

Conclusions

The late-January statement by Minister Moldiz regarding potential DEA cooperation with Bolivia via intelligence-sharing likely opens the door to a wide array of interpretations regarding the future relations of the two governments. Nevertheless, cool heads must prevail and one must not make the assumption that bilateral diplomatic relations will dramatically improve in the near future.

Nevertheless, the December 2014 announcement of renewed U.S.-Cuba relations came as a surprise, so it is conceivable that a breakthrough could also occur between Washington and La Paz in the near future, particularly if the two presidents meet in Panama. Providing DEA intelligence to combat drug trafficking as well as generally positive trade relations could help ease the way for improving diplomatic relations between the United States and Bolivia. If nothing else, this potential opening highlights that Latin American geopolitics are hardly “ideologically-obsessed” and that there will be ample room for pragmatically-motivated decisions.

By: W. Alejandro Sanchez, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

[i] Jeremy McDermott. “Bolivia expels US ambassador Philip Goldberg.” The Telegraph. September 12, 2008 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/bolivia/2801579/Bolivia-expels-US-ambassador-Philip-Goldberg.html

[ii] Associated Press. “U.S. expels Bolivian ambassador; Chavez joins fray.” USA Today. September 11, 2008. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/2008-09-11-bolivian-ambassador-out_N.htm

[iii] “Chief of Mission.” La Embajada. Plurinational State of Bolivia – Embassy in Washington D.C. http://www.bolivia-usa.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=90&Itemid=55&lang=en +

[iv] “Peter M. Brennan. » Embassy of the United States – La Paz, Bolivia. http://bolivia.usembassy.gov/cda.html

[v] Agencies in Cochambaba. “Evo Morales Threatens to close US embassy in Bolivia as leaders weigh in.” July 4, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/05/bolivia-morales-close-us-embassy

[vi] “Evo Morales expulse a agencia de EE.UU.” La Primera Digital. May 2, 20134. http://www.diariolaprimeraperu.com/online/mundo/evo-morales-expulsa-a-agencia-de-ee-uu_137819.html

[vii] “Bolivia.” USAID. Press Release. June 18, 2013. http://www.usaid.gov/where-we-work/latin-american-and-caribbean/bolivia

[viii] EFE. “EEUU y Bolivia firman hoy un acuerdo marco para restablecer la cooperacion.” Finanzas.com. November 11, 2011. http://www.finanzas.com/noticias/bolivia/2011-11-07/592028_eeuu-bolivia-firman-acuerdo-marco.html

[ix] “Declaran presidente reelecto a Evo Morales en Bolivia. “ BBC Mundo. October 18, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/ultimas_noticias/2014/10/141018_ultnot_bolivia_elecciones_resultados_jgc

[x] “En Peru sospechan que el oro sale de contrabando a Bolivia.” Pagina Siete. December 4, 2014. http://www.paginasiete.bo/economia/2014/12/4/peru-sospechan-sale-contrabando-bolivia-40174.html

[xi] “Bush deja sin ATPDEA a Bolivia; la medida rige desde el 15 de Diciembre.” Economia. Los Tiempos. November 27, 2008. http://www.lostiempos.com/diario/actualidad/economia/20081127/bush-deja-sin-atpdea-a-bolivia-la-medida-rige-desde-el-15-de_26087_34518.html

[xii] “Bolivia plantea intercambio de informacion con la DEA en la lucha antidroga.” Pagina Siete. January 29, 2015. http://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2015/1/29/bolivia-plantea-intercambio-informacion-lucha-antidroga-45652.html

[xiii] “Bolivia plantea intercambio de informacion con la DEA en la lucha antidroga.” Pagina Siete. January 29, 2015. http://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2015/1/29/bolivia-plantea-intercambio-informacion-lucha-antidroga-45652.html

[xiv] Christopher Sabatini. “Giving Cuba a Seat at the Table: The 2015 Summit of the Americas.” ForeignPolicy.com / AS-COA.org. December 16, 2015. http://www.as-coa.org/articles/giving-cuba-seat-table-2015-summit-americas

[xv] W. Alejandro Sanchez and Larry Birns. “The Architectonics of Bolivia’s Foreign Policy.” In: Gian Luca and Peter Lambert (eds). Latin American Foreign Policies: Between Ideology and Pragmatism. Palgrave Macmillan. February 2011.

[xvi] Loren Riesenfield. “Bolivia open to working with DEA: Minister.” InSight Crime. February 2, 2015. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-briefs/bolivia-open-to-working-with-dea-minister

[xvii] Agencias. “Descubren seis fabricas de producción de cocaína en Bolivia.” Emol.com. Mundo. October 29, 2013. http://www.emol.com/noticias/internacional/2013/10/29/627140/descubren-seis-fabricas-de-produccion-de-cocaina-en-bolivia.html

[xviii] Agencias. “Descubren seis fabricas de producción de cocaína en Bolivia.” Emol.com. Mundo. October 29, 2013. http://www.emol.com/noticias/internacional/2013/10/29/627140/descubren-seis-fabricas-de-produccion-de-cocaina-en-bolivia.html

[xix] “Bolivia: decomisan 408 kilos de cocaine y una avioneta en tres operaciones.” RPP Noticias. Internacional. December 9, 2014. http://www.rpp.com.pe/2014-12-09-bolivia-decomisan-408-kilos-de-cocaina-y-una-avioneta-en-tres-operaciones-noticia_749398.html

[xx] “Bolivia: decomisan 408 kilos de cocaine y una avioneta en tres operaciones.” RPP Noticias. Internacional. December 9, 2014 http://www.rpp.com.pe/2014-12-09-bolivia-decomisan-408-kilos-de-cocaina-y-una-avioneta-en-tres-operaciones-noticia_749398.html

[xxi] “ONU: Narcos usan Puente aereo entre Bolivia y Peru.” La Estrella del Oriente. December 9, 2014. http://www.laestrelladeloriente.com/index.php/noticias/todas-las-categorias/seguridad/item/14119-onu-narcos-usan-puente-aereo-entre-bolivia-y-peru

[xxii] “El ejercito de Bolivia recibe seis helicopteros H425 fabricados en China.” Infodefensa.com. September 16, 2014. http://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2014/09/16/noticia-ejercito-bolivia-incorporo-helicopteros.html . Also see: “Bolivia ya cuenta con modern helicopter Super Puma, llegaran 6 en total,” ATB Red Nacional. YouTube video. August 1, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRZzA1rD9bc

[xxiii] “Presidente participa en Ampliado de las Seis Federaciones del Tropico en Cochabamba.” BoliviaTV.bo. January 24, 2015. http://www.boliviatv.bo/sitio/nuestra-historia/politica/24-01-2015/c74d90c4246ce245a755abb058415259/presidente-participa-en-ampliado-de-las-seis-federaciones-del-tropico-de-cochabamba.html