How US Private Prisons Profit from Immigrant Detention

By: Melanie Diaz and Timothy Keen, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

In February 2015, a large-scale prison uprising broke out at the Willacy County Correctional Center in Raymondville, Texas. The detention center has experienced riots like this in the past over several other issues, such as inadequate health services, inhumane conditions, and sexual abuse.[i] However, the grievances that sparked this most recent uprising are representative of a larger and more elusive epidemic. The covert and insidious world of the prison industrial complex (PIC)[1] is witnessing the rise of for-profit prisons largely devoid of oversight and regulatory measures, allowing rampant human rights abuses to persist.[ii] Unfortunately, events that took place in Raymondville are far from isolated incidents under this new paradigm.[iii] Operating in the shadows of U.S. bureaucracy, private prison corporations (PPCs) have garnered an infamous reputation for profiting from the government-subsidized business of immigrant detention. Due to this, for-profit prison corporations lobby extensively and provide exorbitant political contributions so that Congress will appropriate more money into immigration enforcement, fueling the revenue of the PIC.

How It Works

The increased detention rate of undocumented immigrants in the United States is primarily caused by a cyclical process occurring between three main actors: government agencies, private prison corporations (PPCs), and Congress. Each of these entities play their own role in adding to the existing problem, but together they create a cycle that is difficult to break. While Congress passes anti-immigration legislations, government agencies enforce these laws and contract with PPCs to facilitate an increasing number of federally convicted detainees. In return, PPCs, whose profits are dependent on the number of incarcerated individuals, rely on lobbying efforts to influence Congress into passing laws and appropriating spending to increase strict immigration policies.[iv] These efforts allow PPCs to reap better financial deals from contracts with government agencies, like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which enforce the anti-immigration laws passed by Congress.[v] These combined factors cause incarceration rates to skyrocket, thus making PPCs the ultimate winner in this deceptive cycle that hinders progressive immigration reforms and the promotion of immigrant rights.

The Role of ICE

The government agency responsible for the enforcement of immigration laws is the Bureau of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), organized under the DHS. According to ICE’s website, the agency’s mission is to identify, apprehend, detain, and remove “criminal aliens and other removable individuals located in the United States.”[vi] In 2005, however, the DHS launched its zero-tolerance Operation Streamline policy, making it a federal crime for undocumented immigrants to enter and re-enter the United States. This immigration policy, which criminalizes more immigrants than before, is one of the primary reasons for the rise in detention rates. Wayne Cornelius, Director of the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies (CCIS) and former President of the Latin American Studies Association, describes the anti-immigration laws throughout the early 1990s as “prevention through deterrence,” and Operation Streamline is just a later policy of this same tactic.[vii]

ICE is attempting to deter immigrants from coming to the United States by criminalizing undocumented entry, and housing migrants in detention centers. The United States has even detained immigrants seeking refugee status, which is an act that is highly controversial in the public arena. The Artesia Detention Center, for example, housed 287 families from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in 2014.[viii] These families were completely made up of mothers and children (no men at all), totaling to 603 people.[ix] Not only is it an international abnormality for children immigrants to face detention, but it is also extremely difficult for these women and children to receive separate hearings to determine their refugee status. Finally, the result of ICE’s attempts to increase the number of detained people is the predictable over-crowding of its own facilities. Therefore, ICE has begun to reach out to PPCs in search of a solution.

How PPCs Benefit

PPCs are a growing industry that recognizes increasing border patrol as a method to secure immigrant detention rates and thus increase their profits. Between 1990 and 2010, the private prison industry in the United States increased by 1600 percent. Annually, PPCs earn about $3 billion USD, with over half of the profit coming from facilities holding undocumented immigrants.[x] In the United States, there are currently 13 privately-operated “Criminal Alien Requirement” (CAR) prisons, with the five in Texas housing almost 14,000 immigrant prisoners altogether in July 2014.[xi] The two biggest corporations running these private prisons are the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), which operates 67 prisons in the United States, and the GEO Group, which operates 95 in the United States and abroad in countries such as the United Kingdom.[xii] These PPCs do not work alone, though. Government agencies often provide the companies with contracts in order to reduce their costs, and over the years, the amount of the public-private contracts have only increased. For example, in 2005, the GEO Group received $33.6 million USD from ICE contracts and CCA received $95 million USD.[xiii] However, by 2012, these ICE contracts had risen to $216 million USD and $208 million USD, respectively.[xiv]

While these contracts allow PPCs a great deal of financial advantage to run their facilities, cost cutting is a common profit-saving tactic, which oftentimes results in inadequate inmate living conditions. For example, despite annual revenues of $1.4 billion USD in 2012, the GEO Group has been criticized for its cost-cutting practices that have created issues, such as insufficient wages and benefits for workers, poor oversight of prisoner maltreatment, and prisoner riots.[xv]

Less Accountability with PPCs

Contracting with PPCs for detention facilities, however, is an issue because they are not held accountable to the same regulations that the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), a government agency that manages federally-operated prisons, sets for public prison facilities[xvi] It has been reported that some PPCs hide behind “trade secrets” and their private status in order to avoid publicizing documents.[xvii] This loophole in the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) of 1967, a federal law allowing for disclosure of governmental documents, allows PPCs to run regardless of human rights abuses that they fail to report to the public due to their fear of budget cuts. For instance, an Amnesty International (AI) report sheds light on the human suffering that is oftentimes found in PPCs, with abuses ranging from malnourishment to a lack of medical assistance for inmates.[xviii] AI also reports high levels of sexual harassment of transgender people who are oftentimes sentenced to long-term solitary confinement due to the lack of better safety precautions.[xix] Yet, despite these human rights violations, the private prison industry continues to operate largely unrestrained as a result of a lacking transparency and ability to circumvent regulatory measures.

However, there have been numerous attempts by Congress to introduce legislation that adds more transparency and accountability to the activities of PPCs. Yet despite the fact that a public-private partnership is still subject to the disclosure laws within FOIA, PPCs have suspiciously lacked in transparency. Legislation changes have repeatedly been put forth to Congress, without success, to cancel PPCs’ usage of FOIA’s loopholes.[xx] This consistent failure is possibly due to PPCs’ lobbying efforts, with CCA spending over $7 million USD on transparency legislation prevention maneuvers since 2005.[xxi]

Another issue with private prisons is that, oftentimes, these prisons are strategically located in rural and isolated areas in an effort to restrict detainees from proper access to due process. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reports that immigrant detainees often suffer from a lack of headway on their immigration cases due to the prisons’ geographical isolation in towns that are too small and underdeveloped to have sufficient lawyers present.[xxii] In addition to this, two recent Supreme Court rulings further restrict access to proper litigation in cases of prisoner maltreatment and abuse. The Correctional Services Corp. vs. Malesko (2001) ruled that private prison companies cannot be subject to and are not liable to violations of constitutional rights.[xxiii] More recently, Minecci vs. Polard (2012) ruled that individual private prison guards could no longer be held accountable for violating prisoners’ constitutional rights so long as the guards are following state laws.[xxiv] These Supreme Court rulings therefore justify and allow private corporations to act more autonomously, with less judicial oversight or accountability.

Money Talks

Proponents of PPCs contracting with the U.S. Government could certainly make the argument that they act within the contours of any typical business. That is, responding to external demand for a particular service; in this case, immigrant detention centers. This argument, however, is only legitimate when the PPCs are not actively involved in altering market demand to suit their monetary interests. Extensive revelations on the lucrative cycle of lobbying and campaign contributions suggest otherwise that private prison corporations, such as CCA, have dubious records of influencing immigration enforcement policy. [xxv]

While PPCs deny allegations of influencing policy through lobbying and campaign contributions, their own statements contradict this. For example, the industry has widely exploited the United States’ post 9-11 paranoia towards immigrants. James E. Hyman, Chairman of the large private prison corporation Cornell Companies, stated: “It is clear that since September 11 there’s a heightened focus on detention…The federal business is the best business for us, and September 11 is increasing that business.”[xxvi]

Exploitation of tragedy and social issues, however, is a norm in the PIC.  In reference to their 2010 annual report, CCA stated that policy reform regarding immigration could affect the number of people arrested and detained, resulting in decreased demand for its detention facilities.[xxvii] In fact, CCA believes that progressive immigration reform would greatly limit their main source of profit: immigrant detainees. Thus, the industry has developed a strategy to maintain their lucrative business model through political channels.

In reference to their 2010 annual report, CCA stated that policy reform regarding immigration could affect the number of people arrested and detained, resulting in decreased demand for its detention facilities.[xxvii] In fact, CCA believes that progressive immigration reform would greatly limit their main source of profit: immigrant detainees. Thus, the industry has developed a strategy to maintain their lucrative business model through political channels.

According to the Justice Policy report titled “Gaming the System”, the strategy of these for-profit prison corporations to influence policy is based on three primary factors: lobbying, campaign contributions, and associations.[xxviii] This tactical trifecta has allowed PPCs to heavily influence U.S. policymaking in order to maintain a status quo, restrict regulatory measures, and enact tougher enforcement laws.

CCA as an Example

CCA representative, Steven Owen, has explicitly remarked that CCA does not lobby to influence immigration enforcement legislation.[xxix] Digging a little deeper into such statements, however, reflects an entirely different reality. According to CCA’s 2013 Annual Report on Political Activity and Lobbying, the for-profit prison corporation openly admits to appropriating funds for lobbying and political contributions to federal and state candidates even in states where inflated corporate contributions are not allowed. In addition, given the recent Supreme Court decision on Citizens United Vs. The Federal Election Commission, which eliminates caps on campaign contributions, CCA’s contributions to political campaigns are made easier by the Supreme Court ruling. In fact, CCA spent a grand total of $769,000 USD on political contributions according to their 2013 Annual Report on political expenditure.[xxx] Their lobbying expenditures in the report, on the other hand, were exponentially higher, with costs on direct and indirect lobbying reaching a whopping $4.4 million USD.[xxxi]

In its 2013 Annual Report, CCA explicitly stated that it focuses on government activities that primarily affect their private detention facilities. CCA also made the assumption that policies regarding the construction and operation of detention facilities are completely separate from immigration enforcement policies. Considering the fact that CCA contracts with ICE, whose chief goal is to enforce legislative measures regarding immigration, CCA’s argument that they do not actively lobby to influence immigration policy is proven fallacious.

In fact, CCA and other similar private prison corporations certainly have a cash incentive to lobby against easing immigration policy. In 2011, CCA received $208 million USD in revenues from ICE contracts, compared to $95 million USD in 2005, according to company filings with the Security and Exchange Commission.[xxxii] Furthermore, in 2011, the Justice Policy Institute found that 50 percent of CCA’s revenues derived from its state contracts.[xxxiii] So without government contracts, CCA would essentially have its profits cut in half. This means that the industry is incentivized to lobby for secured and increased contracts from the government.

Immigration Enforcement Legislation

In 2010, National Public Radio (NPR) undertook an in-depth investigation into the drafting of one of the most controversial immigrant enforcement laws in recent history: Arizona SP1070. Ratified by then Arizona Governor Jan Brewer in 2010, the law entitles law enforcement authorities to arbitrarily arrest people whom are suspected of being in the country illegally.[xxxiv] Critics of the bill believe that it has provoked pervasive racial profiling of Latin American communities based on the law’s provisions to suspect people based solely on how they look or sound. The ACLU reports that the legislation inspired other states to make copycat laws in Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah.[xxxv] The ACLU indicates that Arizona’s state legislators were not the only ones involved with drafting the bill. In fact, it was heavily influenced by external stakeholders, such as PPCs, who would profit from its passing since it would ramp up immigrant incarceration rates.[xxxvi] According to the NPR, several PPC representatives were directly involved with drafting the highly controversial bill.[xxxvii] To make the connection between prison corporations and state legislators elusive to the public, PPCs operated through one of the most conservative and powerful lobbying organizations: The American Legislative Executive Council, otherwise known as ALEC. A conglomeration of powerful corporate industries, ALEC has an infamous track-record for engaging in secretive dialogue between state legislators and corporate representatives to draft model legislation, and CCA is an active member of the organization.[xxxviii]

NPR’s report also revealed that Arizona’s state legislators secretly met with CCA representatives operating through ALEC at the Grant Hyatt Hotel in Washington, D.C.[xxxix] In the meeting, the group of stakeholders discussed, debated and voted on what would become a draft for Arizona’s SB1070, and four months later, the content of the law was almost verbatim.[xl] Coincidentally, 30 of the 36 co-sponsors of the bill received donations over the next six months, from both prison lobbyists and prison companies.[xli] Even more illuminating, Governor of Arizona, Jan Brewer’s top two advisers were former private prison lobbyists. With these revelations in mind, it is clear that PPCs are not only spending vast amounts of money on lobbying and campaign contributions, but are also highly associated and connected to state legislators who are drafting draconian immigration enforcement bills to further their corporate interests.

The private prison industry has not only been involved with writing legislation for Arizona SB1070. Other reports have shed light on its long history with ALEC consisting of a task force that established model legislation including mandatory minimum sentencing, three strikes laws that give repeat offenders 25 years to life, and “truth-in-sentencing” laws that require that prisoners serve most or all of their time without a chance for parole.[xlii]

Quotas & Congressional Appropriations

While PPCs do influence legislation directly, their efforts are also indirect as they concentrate on influencing congressional appropriations. The more appropriations that they can persuade congress to funnel into the DHS, the more money becomes available to them in federal contracts. A prime example of this is the bed quota or occupancy quota.

The bed quota, which mandates that ICE must hold at least 34,000 individuals on a daily basis, is a contractual agreement between ICE and PPCs.[xliii] The quota secures and maintains revenue streams for PPCs by forcing ICE to meet a minimum standard based on an arbitrary quota, which has increased from 10,000 beds to 34,000 over the last 15 years.[xliv] It is particularly unprecedented in that no other law enforcement agencies have occupancy quotas.[xlv] A 2013 report by In the Public Interest, a resource center on privatization and responsible contracting, found that 65 percent of all private prison contracts with the Government include clauses on occupancy quotas.[xlvi] These clauses generally contain a rigid minimum 90 percent occupancy guarantee, with some prisons requiring as much as 100 percent.[xlvii] It is no surprise that PPCs profit from the bed quota and actively lobby for increased appropriations to fuel their lucrative industry. In their 2010 annual report, CCA stated that “filling these available beds would provide substantial growth in revenues, cash flow, and earnings per share.”[xlviii] Since the bed quota officially went into effect after 2010, the share of detention beds operated by PPCs expanded from 49 percent to 59 percent, while 69 percent of all lobbying expenditures by private prison companies have included direct lobbying of DHS appropriations and immigrant detention issues.[xlix] There have been attempts in Congress to eliminate the bed quota from federal contracts with prisons, but all have been shot down due to the immense political leverage of PPCs.

In an effort to ensure that profits from contract conditions are maintained or increased, PPCs have been strategically targeting members of Congress who are in committees that deal with immigration reform. For example, Florida Senator Marco Rubio is a member of the Senate Sub-Committee on Homeland Security and has received $27,300 USD in contributions from the second largest prison corporation, the GEO Group.[l] Another example is Arizona Senator John McCain who received $32,146 USD from CCA, and has since introduced legislation appropriating greater funds for immigration detentions through Operation Streamline (2005).[li] Both McCain and Rubio are also members of the “Gang of Eight,” a bi-partisan group of eight senators who spearheaded the Comprehensive Immigration Reform (CIR) in 2013. PPCs have spent more than $200,000 USD on political contributions and lobbying to “gang-of-eight” members.[lii] Consequently, greater appropriations to the DHS will result in the agency having to find a way to spend that money for that particular year. Increased congressional appropriations to ICE increase the potential for ICE to contract with private prisons. In effect, this pattern can cause greater detainment of undocumented immigrants. In fact, this year’s DHS appropriations act saw an increase of $400 million USD compared to the fiscal year of 2014, and includes amendments that limit President Obama’s recent executive actions on immigration and requires the DHS to enforce current immigration laws.[liii] In 2014, lobbyists from CCA issued six reports lobbying for the passing of the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act of 2015, specifically in regards to funding for the Bureau of Prisons, the Immigration and Enforcement Agency, and the U.S. Marshalls.[liv] In addition, 2014 saw the GEO Group’s 28 reports of lobbying in the following sectors: homeland security and the Immigration and Law Enforcement.[lv] Despite this evidence, however, GEO Group Vice President of Corporate Relations, Pablo Paez, states that the “GEO Group has never directly or indirectly lobbied to influence immigration policy.”[lvi][lvii]

Costs to the American Taxpayer

By far, the most dominant justification for pursuing public-private partnerships with prison corporations is that it saves the state taxpayers’ money, and at face-value it may seem to be true.[lviii]  ICE, which is funded by government taxes, outsources management of prison facilities to the private industry thus transferring costs over to private corporations and not the taxpayers. If only this was the true reality. Put simply, the more Congress succumbs to the private prison industry’s lobbying efforts to funnel more money into the DHS, the more prison populations have increased. And, alas, the taxpayer pays the ultimate costs as increased numbers of detainees eventually drive up taxpayer expenditures.

ICE, which is funded by government taxes, outsources management of prison facilities to the private industry thus transferring costs over to private corporations and not the taxpayers. If only this was the true reality. Put simply, the more Congress succumbs to the private prison industry’s lobbying efforts to funnel more money into the DHS, the more prison populations have increased. And, alas, the taxpayer pays the ultimate costs as increased numbers of detainees eventually drive up taxpayer expenditures.

Today, reports indicate that the United States incarcerates up to 34,000 immigrants per day, costing taxpayers $2 million USD annually.[lix] Every individual detainee costs around $159 taxpayer dollars per day, according to a report by the National Immigration Forum, an immigrant advocacy organization.[lx] Furthermore, the aforementioned bed quota has additionally attributed to hikes in costs to the taxpayer in recent times.[lxi] For example, the third largest for-profit prison corporation, Management and Corp., threatened to sue the State because the contractual condition for the occupancy quota was not fulfilled, claiming the depreciation of inmates resulted in a $10 million USD loss in profits.[lxii] After a series of negotiations, state officials and prison corporate representatives agreed that the State would pay a total of $3 million USD in fines for empty bed fees.[lxiii] This is but one example of how governmental institutions submit to the interests of the powerful for-profit prison industry, costing Congress its legitimacy and taxpayers their hard-earned money.

Failing Policies and Alternatives

With harsher immigration policies and higher rates of immigrant detention, Washington has hoped to deter migrants from coming to the United States. According to the International Detention Coalition, “detention does not deter irregular migrants,” which explains the surge of 51,000 unaccompanied child migrants from Mexico and Central America that arrived to the United States between October 2013 and June 2014.[lxiv] In essence, “prevention through deterrence” has been proven not to work and instead has created other issues, such as unreported human rights abuses in PPCs, more deaths due to new and more dangerous routes into the United States, and increased likelihood of permanent residency for undocumented people. According to a 2014 ACLU report, BOP still had not responded to FOIA requests about oversight within PPCs, causing alarm at the number of human abuse cases that may go unrecorded in these facilities.[lxv] In relation to the increased number of immigrant deaths, Wayne Cornelius, Director of CCIS, has reported that between 1995 and 2004, over 2,460 migrants died on their way to the United States as “the probability of dying versus being apprehended by the Border Patrol has doubled since 1998.”[lxvi] Lastly, in light of stricter anti-immigration policies, undocumented people are now more likely to permanently reside in the United States, since the increasing cost of crossing the border has made cyclical immigration patterns less likely due to immigrants’ fears of being unable to return to the United States after their first arrival. [lxvii]Obviously, current U.S. border policies have a negative impact on migration issues, and given this, Congress has a responsibility to start fixing the failing U.S. immigration policies.

To combat the uncontrolled power of PPCs, the Government must begin increasing means for PPCs’ transparency. The Puente Human Rights Movement also recommends that the Government open an independent office dedicated to monitoring the actions of PPCs and ensuring that they are held accountable for any human rights violations.[lxviii] Furthermore, since taxpayer dollars go into the government agency contracts given to PPCs, the ACLU advocates for Congress to amend the FOIA legislation to apply to PPCs so that the public will have access to the information on what they are funding and that transparency within this industry is heightened.

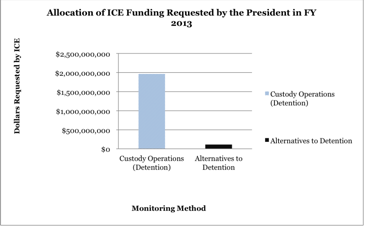

On a brighter note, alternatives to detention do exist. In a House Report by the 112th Congress, it was stated that enrollments in alternatives to detention (ATDs), such as parole or monitoring programs, are as low as $7 USD a day, which is a great financial bargain when compared to the detention costs averaging $159 USD per day.[lxix] It is obvious that costly endeavors to pass anti-immigration policies and deter immigrants with the horror of detention centers are not having the intended effect of limiting immigration. Instead, these tactics are creating more immigrant residency, more immigrant deaths, and more human rights abuses in PPCs, which are gaining enormous annual profits. As another and more progressive alternative to detention, Congress could also consider expanding on development programs in Latin America in order to provide people, including refugees, with alternatives to emigration. Although this will take a longer time to prove successful, it could have the long-lasting impact that Washington is currently aiming for, but without the cost of more immigrant lives.

By: Melanie Diaz and Timothy Keen, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured Image: Immigrants prepare to be unshackled and set free from the Adelanto Detention Facility on November 15, 2013 in Adelanto, California. Photo by John Moore/Getty Images. Accessed from Flikr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/117032936@N08/14484907867/in/photolist-os7SWN-oqJwhC-otUbhK-jhwcJp-hWQTNs-orS7kR-hWRFCk-opkbxi-oGXg8k-i6w9qV-oDMsqU-opjuMj-oi34Xm-jhwkBi-oaDSP9-oHdUz8-ofqbyq-hWRgW3-oHdVsa-oie6Sn-oCs4Tj-oAvypA-ofpRGu-o1KBXX-o1KDtc-hWR4iN-hWQYZE-ojeAet-oAHyrB-ojdEHy-ozYXfB-ogKh1T-ozYVtv-owGEJ1-ogJfR3-okZ2kG-oCdcjD-4PwaxW-4PuaWC-4Prmuu-oWRt-okYXoU-oEeMoi-6Yg8dk-o4YWsP-7UWKvG-8MhJ7y-61fio2-61jyyL-61fmnM

[1] The Prison Industrial Complex refers to the overlapping of for-profit business and government to achieve a particular interest.

[i] Spencer Hsu and Slyvia Moreno, “Border Policy’s Success Strains Resources”, The Washington Post, 2 February 2007, Accessed 30 March 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/01/AR2007020102238.html.

[ii] “Revolt at Ritmo…”, DemocracyNow!.

[iii] “Private Prisons”, American Civil Liberties Union, Accessed 30 March 2015, https://www.aclu.org/issues/mass-incarceration/privatization-criminal-justice/private-prisons?redirect=prisoners-rights/private-prisons.

[iv] “Warehoused and Forgotten: Immigrants Trapped in Our Shadow Private Prison System,” American Civil Liberties Union, June 2014, Accessed 18 March 2015, https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/060614-aclu-car-reportonline.pdf.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] “Enforcement and Removal Operations”, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Accessed 18 March 2015, http://www.ice.gov/ero.

[vii] Wayne Cornelius, “Reforming the Management of Migration Flows from Latin America to the United States”, Brookings: Partnership for the Americas Commission, June 2008, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://www.brookings.edu/about/projects/latin-america/~/media/projects/latin%20america/migration_flows_cornelius.pdf.

[viii] “US: Halt Expansion of Immigrant Family Detention”, Human Rights Watch, 29 July 2014, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/07/29/us-halt-expansion-immigrant-family-detention.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] “Prison Inc: The Secret Industry,” Online Paralegal Degree Center, 2015, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://www.online-paralegal-degree.org/prison-industry/.

[xi] “Warehoused and Forgotten…”, American Civil Liberties Union.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] “Prison Inc….”, Online Paralegal Degree.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] The PRW Staff, “Meet George Zoley, America’s Highest Paid “Corrections Officer”, The Center for Media and Democracy’s PR Watch, 26 November 2013, Accessed 20 March 2015, http://www.prwatch.org/news/2013/11/12320/meet-george-zoley-america%E2%80%99s-highest-paid-%E2%80%9Ccorrections-officer%E2%80%9D.

[xvi] “About Us”, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Accessed 2 April, 2015, http://www.bop.gov/about/.

[xvii] “Warehoused and Forgotten…”, American Civil Liberties Union.

[xviii] “Jailed Without Justice: Immigration Detention in the USA”, Amnesty International, June 2008, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://www.amnestyusa.org/pdfs/JailedWithoutJustice.pdf.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] “Who is CCA”, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Accessed 27 March 2015, http://www.aclu-tn.org/whoiscca.html.

[xxi] Ibid

[xxii] “Warehoused and Forgotten…”, American Civil Liberties Union.

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] Ibid

[xxv] Avivia, Shen, “Private Prison Spend $45 Million On Lobbying, Rake in $5.1 billion for Immigration Detention Alone”, ThinkProgress,, August 3, 2012, Accessed 1 April 2015, http://thinkprogress.org/justice/2012/08/03/627471/private-prisons-spend-45-million-on-lobbying-rake-in-51-billion-for-immigrant-detention-alone/

[xxvi] “Detention and Deportation Consequences of Arizona Immigration Law (SB1070)”, Detention Watch Network, Accessed 1 April, 2015, http://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/SB1070_Talking_Points.

[xxvii] “2010 Annual Report on Form 10-K”, Corrections Corporation of America, 2010, Accessed 25 March 2015, http://www.cca.com/investors/financial-information/annual-reports.

[xxviii] “Gaming the System: How the Political Strategies of Private Prison Companies Promote Ineffective Incarceration Policies”, Justice Policy Institute, June 2011, Accessed 30 March 2015, http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/gaming_the_system.pdf.

[xxix] “Steven Hale, “CCA has eight lobbyists on Capitol Hill—and yet it says it doesn’t lobby on incarceration issues. Maybe it doesn’t have to”, Nashville Scene, 22 May 2014, Accessed 30 March 2015, http://www.nashvillescene.com/nashville/cca-has-eight-lobbyists-on-capitol-hill-andmdash-and-yet-it-says-it-doesnt-lobby-on-incarceration-issues-maybe-it-doesnt-have-to/Content?oid=4171659.

[xxx] “2010 Annual Report on From 10-K”, Corrections Corporation of America.

[xxxi] Catalina Nieto, “The Human Face: The Con to Criminalize Immigrants”, WitnessForPeace, 2 February 2011, Accessed 25 March 2015, http://www.witnessforpeace.org/article.php?id=1064.

[xxxii] Chris Kirkham, “Private Prisons Profit From Immigration Crackdown, Federal and Local Law Enforcement Partnership,” The Huffington Post, 26 November 2013, Accessed 30 March 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/06/07/private-prisons-immigration-federal-law-enforcement_n_1569219.html.

[xxxiii] “Gaming the System…”, Justice Policy Institute.

[xxxiv] Randal Archibold, “Arizona Enacts Stringent Law on Immigration”, The New York Times, 23 April 2010, Accessed 1 April 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/24/us/politics/24immig.html?ref=us&_r=0

[xxxv] “Arizonas SB 1070”, American Civil Liberties Union, Accessed April 2015, https://www.aclu.org/feature/arizonas-sb-1070?redirect=arizonas-sb-1070.

[xxxvi] Ibid

[xxxvii] Laura Sullivan, “Prison Economics Help Drive Ariz. Immigration Law”, National Public Radio, 28 October 2010, Accessed 2 April 2015, http://www.npr.org/2010/10/28/130833741/prison-economics-help-drive-ariz-immigration-law.

[xxxviii] “The Dirty Thirty: Nothing to Celebrate About 30 Years of Corrections Corporation of America”, GrassrootsLeadership, Accessed 1 April 2015, http://grassrootsleadership.org/cca-dirty-30.

[xxxix] Laura Sullivan, “Prison economics help drive…”

[xl] Ibid

[xli] Ibid

[xlii] Ibid

[xliii] “Eliminate the Detention Bed Quota”, National Immigrant Justice Center, Accessed 25 March 2015, https://www.immigrantjustice.org/eliminate-detention-bed-quota.

[xliv] “End the Quota Narrative”, DetentionWatchNetwork, Accessed 25 March 2015, http://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/EndTheQuota.

[xlv] Ibid

[xlvi] “Criminal: How Lockup Quotas and ‘Low-Crime Taxes’ Guarantee Profits for Private Prison Corporations”, In The Public Interest, September 2013, Accessed 25 March 2015, http://www.inthepublicinterest.org/sites/default/files/Criminal-Lockup%20Quota-Report.pdf.

[xlvii] Ibid

[xlviii] “2010 Annual Report on Form 10-K”, Corrections Corporation of America.

[xlix] Christina Filaho, “Adelanto: Unlimited Prison Possibilities”, The Huffington Post, 18 October 2014, Accessed 1 April 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/christina-fialho/adelanto-unlimited-prison_b_5683538.html.

[l]Sasha Chavkin, “Immigrant Reform and Private Prison Cash”, Columbia Journalism Review, 20 February 2013, Accessed 30 March 2015, http://www.cjr.org/united_states_project/key_senators_on_immigration_get_campaign_cash_from_prison_companies.php.

[li]Lee Fang, “Private Prison and Immigration Policy”, The Nation, 27 February 2013, Accessed 28 March 2015, http://www.thenation.com/article/173120/how-private-prisons-game-immigration-system.

[lii] Laura Carlsen, “With Immigration Reform Looming, Private Prisons Lobby to Keep Migrants Behind Bars”, Americas Program, 5 March 2013, Accessed 23 March 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-carlsen/immigration-reform-privation-prisons-lobby_b_2665199.html.

[liii] “House Approves 2015 Homeland Security Appropriations Bill”, The U.S. House of Representtaives, 14 January 2015, Accessed 19 March 2015, http://appropriations.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=393935.

[liv] “Bills Lobbied 2014: Corrections Corporation of America”, Open Secrets, Accessed 19 March 2015, http://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?id=D000021940.

[lv] Ibid

[lvi] “Lobby Report 2014: GeoGroup,” Open Secrets, Accessed 20 March 2015, https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?id=D000022003.

[lvii] Lee Fang, “Disclosure Shows Private Prison Company Misled on Immigration Lobbying”, The Nation, 4 June 2013, Accessed 18 March 2015, http://www.thenation.com/blog/174628/disclosure-shows-private-prison-company-misled-immigration-lobbying.

[lviii] Richard Oppel, “Private Prisons Found to Offer Little in Savings”, The New York Times, 18 May 2011, Accessed 26 April 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/19/us/19prisons.html

[lix] “The Math of Immigration Detention: Runaway Costs for Immigration Detention Do Not Add Up to Sensible Policies”, National Immigration Forum, 22 August 2013, Accessed 1 April 2015, http://immigrationforum.org/blog/themathofimmigrationdetention/.

[lx] Ibid

[lxi] Ibid

[lxii] Ibid

[lxiii] Chris Kirkham, “Prison Quotas Push Lawmakers to Fill Beds, Derail Reform”, The Huffington Post, 20 September 2013, Accessed 25 March 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/19/private-prison-quotas_n_3953483.html.

[lxiv] “Ten things IDC research found about immigration detention,” International Detention Coalition, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://www.idcoalition.org/cap/handbook/capfindings/. ; Alicja M. Duda, “Destined to be the Biggest of Wars – the Humanitarian Crisis of Immigration,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, 27 June 2014, Accessed 20 March 2015, https://coha.org/destined-to-be-the-biggest-of-wars-the-humanitarian-crisis-of-immigration/.

[lxv] “Warehoused and Forgotten…”, American Civil Liberties Union.

[lxvi] Wayne Cornelius, “Evaluating Enhanced US Border Enforcement”, Migration Policy Institute, 1 May 2004, Accessed 16 March 2015, http://icirr.org/sites/default/files/Migration%20Information%20Source%20-%20Evaluating%20Enhanced%20US%20Border%20…pdf.

[lxvii]Wayne Cornelius, “Reforming the Management of Migration Flows from Latin America to the United States”, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, accessed 20 March 2015, http://ccis.ucsd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/WP-170.pdf

[lxviii] “Puente Human Rights Movement Shadow Report: Torture and Human Rights Abuses Within Arizona Immigration Detention Centers”, Puente Human Rights Movement, 15 September 2014, Accessed 18 March 2015, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CAT/Shared%20Documents/USA/INT_CAT_CSS_USA_18544_E.pdf.

[lxix] “112th Congress House Committee Report 112-492”, The House of Representatives, 2013, Accessed 19 March 2015, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/cpquery/?&sid=cp112OLFck&r n=hr492.112&dbname=cp112&&sel=TOC 546602&.