For my Friends, Anything: Temer’s Presidential Dilemma in Brazil

By Dr. Sean Burges, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

There is an old saying in Brazil attributed to Getulio Vargas, one of the country’s presidential giants (1930-1945 and 1951-1954): “For my friends, anything; for my enemies, the law.” Dilma Rousseff, who last week was impeached and then removed from office as Brazil’s president, may well be reflecting ruefully on her predecessor’s cutting wisdom. Indeed, this modest line tells its audience a great deal about why Dilma was fired by Congress and what is likely to transpire over the next two years and four months of the Michael Temer presidency.

One way of explaining Dilma’s fall is her highly noticeable lack of friends. After all, her patron Lula was faced with a far greater scandalous charge in 2005 when his administration was caught buying congressional votes in order to pass his legislative agenda. But Lula also had taken great care to ensure he had lots of friends in Congress. Of course, this was not hard during a time when easy money was engulfing the country thanks to the commodity boom. By the time Dilma took office the Lula-era gravy train had dried up and she had little pork to distribute, leaving her to rely on the less than generous munificence of the Worker’s Party congressional machinery.

Perhaps Dilma could have shored up the necessary friendships by attentively nurturing interpersonal ties with individual legislators in lieu of more visible pay offs. The problem here was that Dilma lacks the irresistible charisma of Lula and was far more interested in focusing on policy matters than practicing what former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso has termed the ‘art of politics’. Throughout her first term in office she reportedly received just thirteen deputies and two senators.

Worse, Dilma gave little indication that she would be responsive when to her friends when needed. During her first year in office she hung six of her ministers out to dry when serious corruption allegations were brought against them. In the complex game of Brazilian coalitional presidentialism this was a menacing omen for her congressional partners represented by these ministers. The resultant unease they felt was only magnified when Dilma stepped aside and apparently did little to constrain the ongoing Lava Jato corruption scandal investigations. These have implicated an astonishing number of prominent political figures from all parties.

Suggestions of malfeasance and the actual pursuit of a politician suspended for their alleged crimes are two very different things—the list of the suspected and the indicted sitting members of Congress is depressingly long.[i]

Dilma’s ostensible puritanism on the issue of corruption might have been overlooked at feeding time by the political elites had the trough continued overflowing. But an economic crisis put an end to the increasingly sparse feast, which meant that Dilma’s pattern of doing little to speed the tortuously slow wheels of Brazilian justice was no longer enough to define ‘friendship’. Fernando Collor de Mello tried to warn her about the dangers of neglecting Congress; his failure to keep supplying the feeding frenzy during a period of economic crisis was a major contributor to his own impeachment when president in 1992.

So where do things go from here? Temer would do well to keep Vargas’s advice of ‘for my friends, anything’ to the fore in his thoughts. His ‘friends’ in the Senate certainly seem to have warned him that they expect everything.

Lost in the excitement of Dilma’s impeachment was a questionable little legal trick quietly negotiated by her Workers’ Party with Supreme Court President Ricardo Lewandowski, and Senate President and Temer loyalist Renan Calheiros. Article 52 of the Brazilian Constitution is clear that an impeached president also loses their right to participate in politics for a period of eight years. Yet the formal communication of Dilma’s impeachment does not cite the Constitutional clause, referring instead to Law 1,079, which simply allows her removal from the presidency without apparently suspending her right to participate in politics, including the right to run for elected office.[ii]

When this became clear Temer was reportedly furious that Calheiros and other members of his coalition in the Senate had pursued this questionable approach to impeachment without clearing it with him. A blunt warning was issued to his cabinet that he would not tolerate dissent from members of his congressional coalition.[iii] Although full of bluster, it is doubtful that the demonstration of presidential rage will have much effect in the face of what is likely a very clear warning from his ‘friends’ that they still expect everything from him, not ‘the law’.

Dilma’s impeachment has been inextricably wrapped up in the ongoing Lava Jato corruption investigation involving Petrobras, the country’s major construction companies, and the leading political parties. Temer, who will be banned from running for public office for eight years from 2018 for campaign violations, has been directly implicated in the affair by Senator Delcídio do Amaral’s plea bargain with prosecutors. The next two in line for the presidency, Chamber of Deputies President Rodrigo Maia and Calheiros, are likewise implicated. As the Lava Jato investigations progress it is beginning to look like almost everyone of political note from any of Brazil’s parties and with a national presence is likely to be somehow involved. Little surprise, then, that some of Temer’s party pushed the impeachment process forward in the hope that it would allow them to squash the corruption investigations. Indeed, Temer’s first Planning Minister Romero Jucá, was fired after he was caught discussing how Dilma’s impeachment could be used to kill off the Lava Jato investigation.[iv] Although considerable more subtle than Jucá’s careless telephone calls, Calheiros’ gambit looks very much like a reminder that the ‘friends’ expect Temer to quietly squelch the investigative zeal of the judiciary.

The above has created a serious problem for Brazil. It increasingly looks like corruption is endemic in the political class irrespective of one’s ideological leanings. Given the forced retirement looming in his near future, Temer could conceivably take on the role of philosopher king and try to begin a comprehensive cleanup of national politics. The question is whether or not such a policy path would initiate formal proceedings against him. As Calheiros rather publicly reminded Temer, Congress is not under the President’s thumb. If anything the situation may well be the reverse. Moreover, any progress on the badly needed comprehensive political reform necessary to root out systematic corruption will require active consent from the approximately sixty percent of Congress currently under criminal investigation. For many this sounds too much like ‘the law’ and not the ‘anything’ they expect. The political future for Brazil thus looks bleak as ‘friends’ look after more earnest ‘friends’ in Brasília.

The question for Brazilian democracy is whether civil society and the business community can be expected to tire of the situation and try to erase Vargas’ saying from the national lexicon. To do so will take strong political leadership working with a deeply entrenched ethical guide. Despite the growing political protests in Brazil it still remains unclear where we might find the next generation of political leaders and if anyone will be able to trust them as they emerge. Temer’s risky, but possibly only available bet appears to be on restarting the national economy and making everyone a friend willing to turn a blind eye to the law, bent as it might be.

By Dr. Sean Burges, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Sean W Burges is a senior research fellow with the Washington DC-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs as well as deputy director of the Australian National Centre for Latin American Studies at the Australian National University and a visiting professor at Carleton University. He is the author of Brazilian Foreign Policy After the Cold War (Florida, 2009), Brazil in the World: The International Relations of a South American Giant (Manchester, 2017), and over two dozen scholarly articles and chapters on Brazilian foreign policy and inter-American affairs.

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

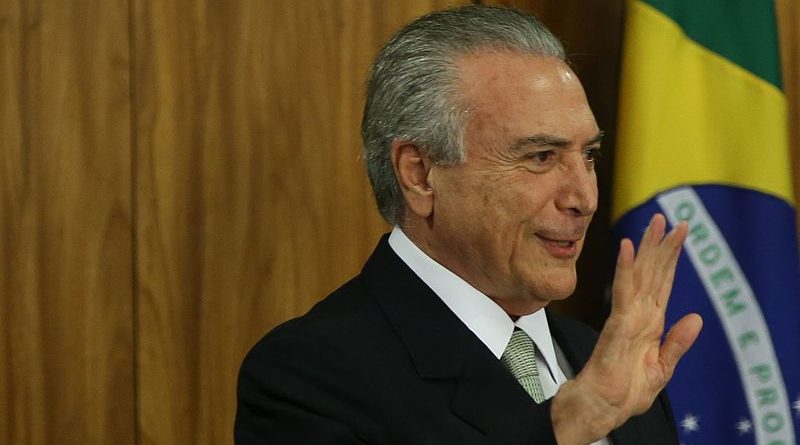

Featured image: Posse de Michel Temer. Taken from Wikimedia.

[i] Poletti, Luma. “Veja a Lista Dos Parlamentares Que São Réus No STF.” Congresso Em Foco RSS. August 3, 2016. Accessed September 09, 2016. http://congressoemfoco.uol.com.br/noticias/veja-a-lista-dos-parlamentares-que-sao-reus-no-stf/.

[ii] De Souza, Josias. “Avisado, Lewandowski Preparou-se Para Manobra Que Suavizou Punição De Dilma – Política – Política.” Política. January 9, 2016. Accessed September 09, 2016. http://josiasdesouza.blogosfera.uol.com.br/2016/09/01/avisado-lewandowski-preparou-se-para-manobra-que-suavizou-punicao-de-dilma/.

[iii] Uribe, Gustavo, Valdo Cruz, and Eduardo Cucolo. “Em Discurso, Temer Diz Que Não Irá Tolerar Ser Chamado De Golpista.” Folha De S.Paulo. August 31, 2016. Accessed September 09, 2016. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2016/08/1809000-em-discurso-temer-diz-que-nao-ira-tolerar-ser-chamado-de-golpista.shtml.

[iv] Valente, Rubens. “Em Diálogos Gravados, Jucá Fala Em Pacto Para Deter Avanço Da Lava Jato.” Folha De S.Paulo. May 23, 2016. Accessed September 09, 2016. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2016/05/1774018-em-dialogos-gravados-juca-fala-em-pacto-para-deter-avanco-da-lava-jato.shtml.