En Route to a Failed State—Corruption in the Paraguayan Legal System, the Illicit Market, and Transnational Security

President Fernando Lugo’s speedy impeachment process highlighted the corrupt Paraguayan legal system that continues to enable the political elite to place their interests above those of the citizenry. The Colorado Party used violence between campesinos and the National Police to galvanize Congress and push Lugo, who had consistently clashed with the Colorado Party, out of office. Although many Paraguayans had lost faith in the former president, the motive for the impeachment was, at the very least, self-serving. This corruption is not a new phenomenon in Paraguay politics, as it stretches back to land distribution regimes after the War of the Triple Alliance. However, the Paraguayan populace has begun to show resistance against this historic trend. On May 25, more than 5,000 Paraguayans protested in Asunción against the appropriation of additional congressional funds to the Supreme Court for Electoral Justice (TSJE), an institution that is infamous for bolstering caudillismo in the government. Ultimately, this struggle for access to the state lies at the heart of Paraguayan culture and fosters institutionalized corruption in the country’s legal and political systems.

The government’s failure to provide welfare and security for its citizenry has not only led to the largest illicit market in the Western Hemisphere, centered in Ciudad del Este. But also, this systematized failure has resulted in growing trepidation from its neighbors over trafficking and augmented international alarm concerning organized crime and terrorist connections operating throughout the region. To his credit, Lugo supported land redistribution and the rights of the Paraguayan poor, as he introduced legislation to improve low-income housing, treatment in public hospitals and income inequality. Further, he gave rights to the voiceless Paraguayan indigenous population and refused to take a salary because he believed money belonged to the citizens. But he ran on an anti-corruption platform, and the corruption related reforms he was able to pass through the opposition-controlled Congress at best only superficially changed policy because they left the caudillos in place. Although Paraguay has yet to reach the ominous “failed state” status, the growing distrust between the government and its people threatens both internal and external security while adversely affecting trade relations with the other Southern Cone countries and the United States.

Corruption in the Legal Sector

Corruption in Paraguay became an art form under the Alfredo Stroessner military dictatorship when military officials helped organize and participated in the narcotics and contraband trade with complete impunity. The United States accused the dictator’s son, Colonel Gustavo Stroessner, of running an international cocaine ring, setting a precedent for legal and military involvement with the illicit trade.(1) When the dictatorship ended bloodily in 1989, this connection became institutionalized. In February 2011, Brazilian authorities arrested Colonel Waldimiro Ausberto Gill Bejarano on charges of smuggling thousands of dollars worth of prescription drugs across the border. Similarly, the National Police arrested Ciudad del Este’s former police chief Hermes Enrique Argaña in February 2012 on drug smuggling charges. Argaña had previously been convicted of murder in 1990, highlighting the historic and pervasive corruption in the police force that allowed him to both secure his freedom and rejoin Ciudad del Este’s police.(2) This connection between the legal enforcement and illegal activity went a long way to destroy Paraguayans’ trust of the police, leading to a rise in privatized security and subsequent extra-judicial killings.(3) According to a La Nación poll in May 2012, 76 percent of respondents had no confidence in the national police, and 90 percent believed that crime had increased in the previous year.(4) These statistics signify that Paraguay has lost institutional control of—or rather never gained control of—its legal system, a reality that helped to doom former President Lugo, who ran on an anti-corruption, anti-violence platform.

The corruption easily extends from the local police to the Paraguayan Supreme Court and the TSJE. The conservative research group Freedom House reported in 2011 that, in Paraguay, “courts are inefficient and political interference in the judiciary is a serious problem, as politicians routinely pressure judges and block investigation.”(5) The Paraguayan constitution permits criminal detention without trial until the accused has completed the minimum sentence for the alleged crime. This policy continues to support illegal imprisonment and torture during incarceration, particularly in rural areas where the police repress indigenous communities instead of halting smuggling operations. Moreover, although the judiciary is nominally nonpartisan, over 60 percent of judges are members of the historically all-powerful Colorado Party, with bribes and fear of prosecution as its modus operandi. The International Intellectual Property Alliance reported that, to support this current system, the Supreme Court refuses to investigate allegedly corrupt judges, although Plan Umbral I, embraced by its sitting judiciary, created mechanisms through which citizens can file such complaints and request inquiries.(6) When prosecutors do call forth investigations, the courts have generally disregarded misconduct as well as refused to hear the cases against tainted judges. However, Paraguayan judges rarely call this investigatory process into action, as there is no mechanism to anonymously file such reports, thus promoting an aura of fear that filing a complaint is likely to prejudice judges hearing existing cases.

The federal government tends to bolster this systematic corruption by creating a large client network to augment electoral success. Congress recently was embroiled in a conflict over extending funds to the TSJE, as it continues to allot cash to support political operatives. Because many social services in Paraguay lag behind comparable institutions in neighboring Latin American countries, Paraguayans believe that budget increases often represent serious misallocations of public funds. The TSJE is the body responsible for the administration of and legal decisions regarding all electoral events in Paraguay, and because the appointments are made via a quota system rather than a merit-based one, many Paraguayans see this panel as a symbol of court corruption.(7) However, beyond the TSJE, the entire judicial system, from the Supreme Court of Justice to the lower courts, is subject to politicized bargaining, with nominations made on the basis of political service and instances of loyalty. Paraguayans view the courts with an even more pessimistic attitude than the police force, with only 11 percent possessing any confidence in the application of equality before the law and less than one third espousing faith in the judicial authorities.(8) Therefore, the higher courts as well as Congress continue to support the corruption routinely seen on the lower levels of the political and legal system.

Economic Implications

Although corruption exists in almost every sector in Paraguay, the most fraudulent undertakings principally occur around the illicit market in the Tri-Border Area (TBA). The border area between Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil—dotted by the cities of Ciudad del Este, Puerto Iguazú, and Foz do Iguaçu—forms the TBA, a region that has long been scrutinized for drug trafficking, the smuggling of goods, and organized crime syndicates. The Friendship Bridge spanning the Paraná River between Foz do Iguaçu and Ciudad del Este carries a majority of the $1.2 billion USD in bilateral trade that passes between Brazil and Paraguay, a relationship that accounts for nearly a quarter of all Paraguayan legal trade.(9) The United States government predicted that roughly 30,000 to 40,000 people and 20,000 vehicles cross the Friendship Bridge daily and that immigration officials check only 10 percent of the baggage or vehicle loads.(10) Although the region technically falls under a free trade zone, tourist purchases of over $300 USD are subject to a base tariff. Due to the arbitrage possible between the two countries, along with the availability in Paraguay of many goods banned in Brazil, smugglers routinely bribe border officials in order to avoid paying excise taxes, highlighting the permeability of the border, which has fostered a deep-seated smuggling culture.

Allegations regarding Paraguayan military support for drug smugglers recently have led to a growing distrust between Brazil and Paraguay. For example, in April 2011, more than 6,000 rounds of ammunition went missing from a Paraguayan air force base in the municipality of Luque, raising concerns that the military was trafficking weapons to criminal groups and drug smugglers. Days after the event, several anonymous military officers expressed their concern to local media over corruption in their ranks.(11) Addressing the speculation that Brazilian drug gangs have moved some of their operations into Paraguay, Brazil’s Federal Police Representative Antonio Celso dos Santos commented to the newspaper Folha de São Paulo, “If you are a criminal and must find a place to work, you will go to a place with little police presence, where the chance of getting caught is small, there is great mobility, and which is close to the consumer market. That place is Paraguay.”(12) These concerns led Brazil to pledge additional funds to close the border through increasing patrols and instituting a satellite surveillance program. The border tensions heightened in October when Paraguayan marines fired at Brazilian border police as the Brazilian contingent attempted to apprehend a drug smuggling barge on the Paraná River.(13) This alleged Paraguayan backup for the drug cartels operating from Paraguayan terrain served only to amplify the trends toward police corruption as well as governmental clientelism, both of which sustain the illicit trade.

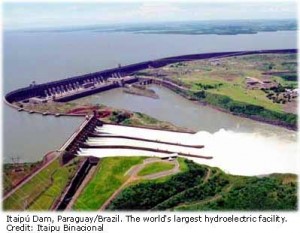

Ciudad del Este is becoming one of the most critical commercial centers in the hemisphere. The city has played an increasingly important industrial role, contributing to Paraguay’s economic explosion in recent years, but it also hosts a rapidly expanding market for illicit goods and money laundering. Global Financial Integrity estimated that illicit cash flows in Paraguay amounted to $1.66 billion USD in 2008, increasing nearly 600 percent from 2000. Most of this growth has occurred in the past five years when illicit flows into Paraguay rose by 30 percent, compared to a 6 percent increase overall in the Western Hemisphere.(14) Further, reports estimate that unofficial exports of contraband total $4 billion USD, the same level as its official, legal exports. The National Police balk when asked to take action against the landlords who enable the piracy, because Ciudad del Este’s district attorney’s office consistently denies attempts to apply landlord liability laws.(15) Aided by both the tourism opportunities in conjunction with the nearby Iguazú Falls and the Itaipú Dam, which generates nearly $300 USD million annually in energy sales to Brazil, Ciudad del Este and the TBA also function as a lucrative funding source for both individuals and their political parties via the fraudulent state-owned enterprises. Thus, this region not only ties into the booming local illicit market, but also into the national patron-client networks.

In addition to simply pirating electronics and smuggling illegal goods, the Paraguayan illicit market also acts as an essential stop for drug trade networks and as an integral money-laundering center for organized crime syndicates. Since the beginning of 2011, authorities in southern Bolivia, Paraguay, and western Brazil have recovered 10 drug-smuggling planes, suggesting that cartels have begun to divert traffic along the Andean route via Paraguay to distract authorities from their suspected movements. President Lugo consistently demoted border security issues to a lower rank on his security agenda than threats posed by the Paraguayan People’s Army guerrillas, which resulted in a steep decline of security patrols. For example, Alto Paraguay, a 31,000 square-mile municipality renowned for drug trafficking, has “just 90 police officers, six patrol cars, no patrol boats, and no capacity to monitor flights.”(16) Weak controls on the financial sector, combined with torpor regarding border enforcement, contribute to the increased laundering activities in the region. The U.S. Department of State has characterized the TBA as a “major drug-transit and money-laundering area,” and estimates its trade houses launder millions to the United States annually.(17) Many Paraguayans believe that the courts do not have the jurisdiction to prosecute the laundering centers, and few trust the legal system to fully enforce the law; thus, this laundering, and consequently the drug trafficking that supports these money flows, will only continue to grow as other major drug-supplying countries slowly eradicate cartels from their border regions.

Paraguayan and Transnational Security Concerns

The illicit market and institutionalized corruption have raised transnational security concerns beyond Paraguay’s borders. As the largest producer of marijuana in South America, Paraguay increasingly gained attention from the United States over Lugo’s de facto decision to carry out a reduction in drug-eradication-policy priorities due to recent required budget cuts.(18) Although Paraguay has reliably partnered with the United States on both terrorism and drug-related concerns, Asunción has deftly thwarted American attempts to develop a military presence for itself in Paraguay and has rejected the expansion of Washington’s “New Horizons” program in South America, conforming to the shared policy in the Southern Cone.(19) Without reliable political and social institutions, Paraguay struggles to control drug trafficking, an issue that clearly already has negatively affected Asunción’s relations with its neighbors, and threatens to harm its seemingly positive relationship with the United States. Moreover, the lack of internal security threatens the Paraguayan populace, due to an increase in drug-related violence in recent years, especially in the rural areas where little to no police presence exists to protect impoverished Paraguayans from the cartels.

Although ideology-based terrorism has diminished in South America during the past decade, drug trafficking and organized crime have allegedly become increasingly connected to surging international money flows that support terrorist activities in other regions, including Mexico. The United States has identified the TBA as one of the foremost regions for terrorist activity in the Western Hemisphere.(20) Roughly 15,000 Paraguayans of Lebanese descent live in the TBA with connections to the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon, an area known as a drug-trafficking hub and an important locus of Hezbollah’s criminal activity. Hence, RAND reports, “The tri-border area has emerged as the most important financial center for Islamic terrorism outside the Middle East, channeling $20 USD million annually to Hezbollah.”(21) Nevertheless, little evidence beyond bank statements exists to buttress this charge, and most of the drug trade has been pushed from the TBA into northern Paraguay. However, the United States believes illegal activities in the TBA still support Chinese and Asian mafias, reflecting the porous borders and dearth of consistent security forces found in much of the country that would act to dissuade such activities.

Many of the assertions regarding this criminal activity remain unproven, and it is difficult to corroborate the amount of terrorist activity or funds developed in the region; however, some terrorist connections and organized crime likely do exist in Paraguay and present a troubling security concern for the landlocked country. Consequences from the crime networks and illicit economic activity clearly spill over into the hands of the domestic population as well as into Paraguay’s links to international trade; therefore, border security and reducing illegal activity is paramount to maintaining Paraguay’s perception as an emerging market and a democratizing country. However, Paraguay cannot control these two issues without first reforming the caudillismo within its political system and the corruption in the legal system. Thus, the institutional failures within Paraguay’s government have led to, and aggravated, these transnational security concerns.

Conclusion

When Lugo was elected president in 2008, he promised political reforms and a curtailment of the deep-rooted corruption left over from the Colorado Party’s 60 years in power. However, burdened by a congressional minority and growing domestic issues, Lugo failed to enact the proper reforms necessary to restore the Paraguayan populace’s trust in political institutions. With a high court system that routinely supports the Colorado Party, and clientelism reaching all facets of Paraguayan society, newly chosen President Federico Franco faces many difficulties if he is to reduce the illicit market, which would allow him to address the related major security concerns. President Franco must tackle these issues to help justify the impeachment process. Yet he must do so without the help of international partners due to the lack of support for his rule throughout Latin America, particularly with the neighboring Mercosur nations.

It is imperative that reforms start from above, namely from the high courts and Congress, and work their way down to the local contributors. Recent steps, such as raising the National Police’s salary by 40 percent, its first raise in nearly 10 years, and changing police uniforms throughout Paraguay, are promising initial steps. They will help to develop a new face for these institutions and encourage accountability from below by taking away the opportunity cost for corruption. However, more reforms must be instituted to help dislodge those who control the patron-client networks, and hence allow the illicit market to persist. Franco must enact judicial reform, destroying the quota system and replacing it with a transparent system of appointments based on merit instead of loyalty, especially in the Supreme Court and within the TSJE. Helping to simplify the system for political allocation of personnel awards with a streamlined approval process and an age limit for court appointments would allow for greater turnover. Most of all, transparency in all levels of the legal and political system should become one of the first steps in rekindling the bond between the citizenry and the government.

It has been routinely said that corruption runs through the veins of the Paraguayan political and legal systems. If the courts fail to prosecute those involved in patron-client networks, the police fail to arrest drug smugglers and common criminals, and the ingrained politicians fail to draft reform measures, then these institutions will continue to support the illicit market and entrenched drug trade, both of which have been connected to organized crime syndicates and terrorist organizations. Brazil and Argentina’s concerns over border protection and drug cartel activity within Paraguay highlight the escalating international trepidations regarding security. Finally, the Paraguayan people themselves trust neither the police nor the courts. Nor do they believe that the government has enacted sufficient change to reduce crime. Thus, Paraguay could be heading toward “failed state” status if Asunción does not seriously approach transparent reform in a professional and responsible manner. Though corruption often becomes a signature trait of Paraguayan leaders, such as Stroessner and Lugo, it cannot be attributed to a personal weakness, but rather institutions that make the system vulnerable to collapse.

To view citations, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.