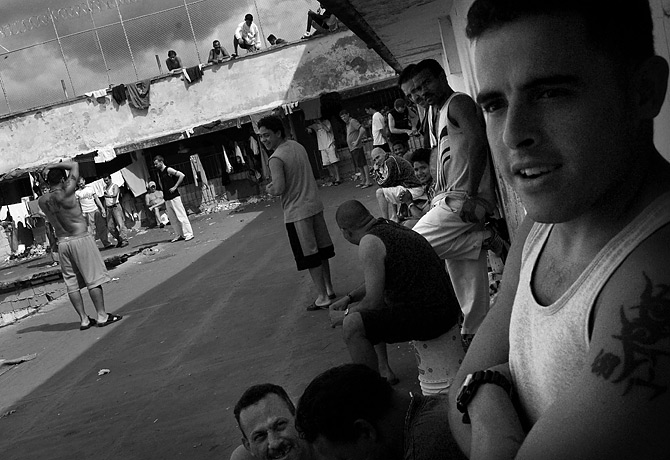

Crowded and Grim: Inside Venezuela’s Prisons

- On July 14th, a stand-off in the Venezuelan prison El Rodeo II reached a peaceful conclusion after 27 days of simmering conflict.

- Violence in Venezuelan penal facilities has steadily worsened in recent years.

- Overcrowding remains a fundamental fact of life for the country’s prison system, and is exacerbated by Venezuela’s tendency to compound prisoners beyond the legal time frame.

On June 12, an outbreak of gang-related violence in Venezuela’s El Rodeo I prison, located on the outskirts of the capital city of Caracas, predictably instigated a 27-day stand-off between inmates and military guards at the neighboring El Rodeo II facility. The negotiations that took place on July 14 between government officials and rebellious inmates led to the peaceful resolution of the conflict and the subsequent removal of 1,019 inmates from the penitentiary.[1] The violent confrontations at El Rodeo, in addition to the relocation of prisoners, drew attention to the ticking time bomb of the overcrowded prison system. Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez has approved various reform measures in order to improve the nation’s prison system, but thus far bureaucratic adjustments and increased funding have made only cosmetic changes in the grossly inadequate penitentiary system.

El Rodeo

An altercation between two rival gangs in El Rodeo I prison, located on the outskirts of the Venezuelan capital of Caracas, exploded into violence on June 12, 2011. This confrontation left 25 dead and many more injured.[2] After mollifying the situation at El Rodeo I, the National Guard attempted to control tension at a neighboring wing of the facility, El Rodeo II, on June 17. Inmates of El Rodeo II greeted the soldiers with a “barrage of gunfire.” It is unclear how the prisoners came into possession of these weapons, but gang activity and the presence of such heavy-duty contraband is common within Venezuelan cell blocks.[3] The first days of the conflict were characterized by the detonation of hand grenades and the frequent deployment of tear gas.[4] The stand-off endured for nearly one month, but finally ended with peaceful negotiations between the inmates and security forces. Though it appears that the inmates were treated fairly, Venezuelan prisons are notorious for their wrenching human rights violations.[5]

Crowded

As a result of the conflict, 831 inmates will be relocated to Yare 2 and Tocuyito prisons.[6] The transfer of such a significant number of prisoners will place profound strain on the country’s overcrowded penal system. In 2006, the Inter-American Court concluded that La Pica prison, in eastern Venezuela, was dangerously understaffed, with “an average ratio of one corrections officer to every 63 inmates.”[7] Following its investigation, the Inter-American Court ordered that Venezuela take immediate action to rectify the prison’s infrastructural shortcomings; however, as reported by Humberto Prado of the Venezuelan Prison Observatory (OPV), Caracas made no efforts to comply with the order.[8]

According to Prado, Venezuela’s penal system has a higher homicide rate than any other Latin American prison system.[9] A significant portion of the violence is attributable to overcrowding, as more than 44,500 prisoners are currently housed in a system designed for just 15,000.[10] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has expressed concerns akin to those of Prado, and has urged the Venezuelan government “to take action to tackle violence and insecurity in its prisons as well as to protect the human rights of inmates.”[11] The feeble, often corrupt security systems in place enable frequent violent outbursts within these institutions, as inmates operate with only intermittent supervision. Though President Chávez made prison reform a priority for 2011, his administration’s efforts have yet to reap tangible results.

Government Spending

Increased funding has done little to improve Venezuelan accommodations. Minister of the Interior Tarek El Aissami claims that the government has spent almost USD 100 million to “humanize” living conditions in the country’s jails, but agreed that these efforts have been unable to combat, “the sheer drama, urgency and complexity of the problems afflicting the prison system.” [12],[13] Chávez created the Ministry of Comprehensive Care for the Prison Service to supervise the system as a whole and to guarantee the preservation of prisoners’ human rights, but such bureaucratic modifications have proven futile.[14] Instead of focusing solely on the reparation of the prison system itself, the Chávez administration should aim to decrease the amount of prisoners held on remand, thus alleviating the debilitating strain on staff and resources caused by overcrowding.

In 2007, 62.6 percent of incarcerated individuals in Venezuela were being held on remand.[15] Marianela Sánchez, a lawyer at OVP, explained, “Above and beyond the harsh conditions and the continuous risk to life, what prisoners resent most are the procedural delays that keep them warehoused without justice having been served in their case.”[16]According to Venezuelan law, it is illegal to detain an individual for more than two years without legal sentencing. However, Sánchez claims that far too many prisoners have been held on remand past the legal time frame proscribed by the country’s constitution, and that, “The justice system gets around this by deferment of procedures, a legal ruse that brings back the bad old days. Deprivation of freedom has again become the rule rather than the exception in our justice system.”[17] The processing and sentencing of accused criminals within legal time frames is an important first step in curtailing overcrowding and reducing violent confrontations.

Conclusion

The troubling state of Venezuela’s prisons represents a deeper regional issue for Latin America. A 2007 study conducted by the United Nations determined that 25 of 26 Latin American nations had severely overcrowded prison systems, and identified 19 of these facilities as “critical.”[18] Since 2007, very few initiatives have succeeded in improving Latin American prison systems. The most recent crisis in El Rodeo exemplifies the calamity of overcrowding in the prison system and demonstrates the need to swiftly and accurately prosecute and incarcerate convicted criminals. The placement of defendants in already over-burdened facilities contributes to overcrowding, making it far more difficult to control and prevent violent confrontations within the institutions. President Chávez has made some effort to increase government funding and bureaucratic oversight of the Venezuelan penal system, but it is clear that these initiatives will fail to enact legitimate long-term change without legal initiatives to expedite the sentencing of remanded prisoners.

References for this article can be found here.