Chávez’s Appointment of His Second-In-Command

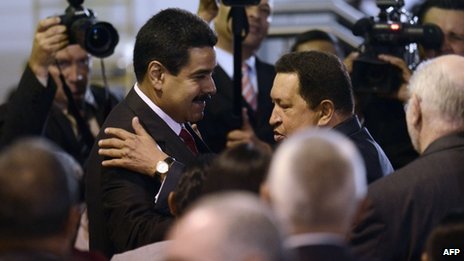

Immediately after winning the October 7th election, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez named veteran Chavista Nicolás Maduro to be the country’s new Vice President. The choice solidifies Maduro’s steadfast loyalty to the Venezuelan strong man and comes at a time of record electoral votes in Chávez’s favor. However, there is room for an analysis of the Chávez tradition of constant reshuffling in his cabinet in the past and how Maduro could change this previously accepted perception of illiberal practices aimed at silencing opposition voices.

The newly reelected President must learn from the past and recognize the influence of Venezuelans who vehemently oppose his administration. After initiating legislation and political measures in 2007 entirely tailored to minimizing the opposition’s impact on the country’s political landscape, Chávez experienced significant setbacks evidenced in citizen response and international interpretation. One such initiative was the creation of a presidential committee devoid of any opposition members to draft constitutional changes. His government also produced a list of citizens forbidden from running for office under suspicions of corruption. The government blacklist consisted of upwards of 270 people, including leading opposition figures, and, furthermore, after the 2008 elections, Chávez denied opposition governors federal funding to which they were entitled.1

Since 2006, Maduro has served as Chávez’s Foreign Minister, being appointed to the post after his previous tenure as President of the National Assembly had ended2. That legislative position, along with his working-class roots as a former Caracas bus driver, highlights the Chavismo principle of anti-bourgeoisie socialism that has consistently drawn supporters from segments of Venezuela’s economically disenfranchised population. For Chávez and the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PDVSA), the appointment of Maduro to a pivotal position in the government’s hierarchy continues a logical narrative of the advancement of the working class with his potential subsequent role as President, should Chávez meet with terminal health problems sometime in the near future. To further take into account that Maduro was Cuba’s favorite candidate for the country’s top domestic position suggests that Chávez might continue to pursue radical measures as opposed to remaining committed to campaign promises.

What does the new VP Selection Mean for Venezuela?

Maduro’s appointment as vice president relates to a larger issue of criticism of Venezuela’s political standing in the region in the past for its illiberal democratic practices, which have been known as a partial democracy and hybrid regimes. If el Comandante’s legacies are truly to stand the test of time, he must realize that a constant shuffling of cabinet members can lead to internal dysfunction. The process is entirely subject to what many critics have dismissed as nepotistic political appointments, especially given that Chávez appointees rarely knew prior to his announcements that they were destined to be selected. Although usually necessary, Venezuela’s recent practice of facilitating quick turnovers for government appointed officials suggests certain levels of institutional weakness. Cecilia Martinez-Gallardo, of the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, has spoken to this point, contending, “appointments [are] the preferred response of politically and institutionally weak presidents.”3 In other words, ailing presidencies tend to make use of constant and frequent cabinet changes in an effort to frantically adapt to new developments in their country’s electoral demographics.

A different view beyond the Martinez-Gallardo analysis would state that frequent cabinet change implies a strong commitment to democracy. However, the ultimate motives for the latest cabinet switch remain to be seen in the case of Venezuela. In the past, Chávez has used regular cabinet shifts to respond to periods of political shock, which some have used as evidence that his actions are replete with illiberal motives. This is further evidenced by the Venezuelan leader’s questionable hesitation to work on a multi-partisan basis. Of course, one frequent charge following Chávez’s lack of multi-partisanship is the claim that such shakeups are often strategically orchestrated to accomplish the perpetual task of silencing the opposition.

Peru’s Humala Flutters His Political Feathers

Peru is an interesting case study of a nation balancing an ideological mission with the pragmatic needs of the country. Peruvian President Ollanta Humala is at least trying to demonstrate that he is committed to balance policy through unflappable political gamesmanship. Last July, Miguel Castilla Rubio became the Minister of Finance for Peru despite the fact that he had served under the previous president and now ideological foe, Alan García. Humala represents the left-wing of the Peruvian Nationalist Party, rife with nationalistic and socialistic sentiment. In any event, he has succeeded in being a rational and effective leader comparable to Lula in Brazil. Furthermore, despite party ideology and past transitions, he is still significantly perceived as less radical than Chávez. This re-alignment occurred after García took a more left-of-center track in moving towards a social democracy rather than a democratic socialist form of government. Despite Castilla Rubio’s adherence to pro-market economics, Humala mainly appointed him to pacify concerns of investment opportunities in the country more than anything else.

More of the same in Venezuela?

In Venezuela, Chávez’s appointment of Maduro paves the road nicely for a potentially polemic showdown as former Vice President, Elias Jaua, can now be expected to run for governor of the Miranda state in December against familiar presidential challenger, Henrique Capriles. It remains to be seen if Chávez will work to dispel dissonance over his hard left agenda or will only provide more instances of suppressing the opposition in order to stay in power via overwhelmingly tough measures.

As Nicholas Watson, a Bogotá-based analyst, stated, “the interesting thing to watch as of now [in Venezuela] will be whether this is the occasion Maduro takes on more responsibility than his predecessors and gets involved in a more substantive way in government business, which would be a sign that Chavez is indeed grooming him as his successor.”4 That Chávez even has been given the opportunity to prepare a successor is testimony to his legacy as a strong Venezuelan political figure and icon. His re-election is evidence of a strong, almost worshipping following in the country. However, his regime’s brand of democracy stands in jeopardy should Chávez continue to make decisions based on personal loyalty rather than ongoing political needs, especially one as serious as appointing the second-in-command in such a tumultuous country as Venezuela.

Kate Hayden, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

Sources:

1 Javier Corrales. “A Setback for Chavez,” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 1 (2011).

2 Fabiola Sanchez and Ian James, “Venezuela’s New VP to be Key Figure for Chavez,” The News Tribune, October 11, 2012, http://www.thenewstribune.com/2012/10/11/2328341/venezuelas-new-vp-to-be-key-figure.html

3 Cecilia Martinez-Gallardo, “Designing Cabinets: Presidential Politics and Cabinet Instability in Latin America,” Kellogg Institute for International Studies, January 2011. http://kellogg.nd.edu/publications/workingpapers/WPS/375.pd

4 Fabiola Sanchez and Ian James, “Venezuela’s New VP to be Key Figure for Chavez,” The News Tribune, October 11, 2012, http://www.thenewstribune.com/2012/10/11/2328341/venezuelas-new-vp-to-be-key-figure.html