Canada’s Controversial Engagement in Honduras

By: Sabrina Escalera-Flexhaug, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Increasing Involvement

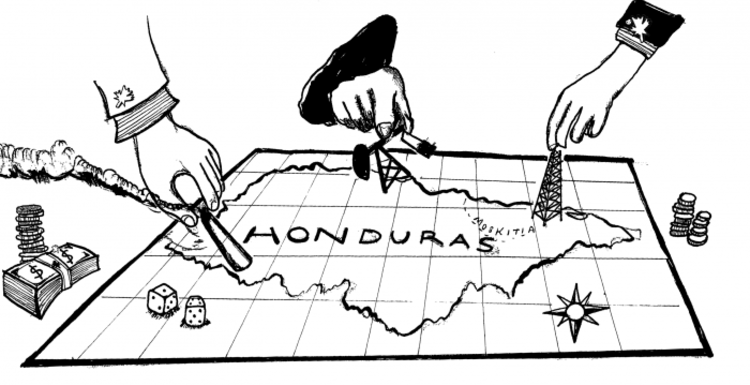

Since Hurricane Mitch struck Honduras in 1998, Canada has cast an increasingly long shadow over the small Central American country’s economy and policy; a presence that has grown stronger since Honduras’ controversial 2009 coup. The self-proclaimed peacekeepers have since built a stronghold over Honduras via investment in industries and support for the illegitimate government created in the wake of the coup. Canada’s relationship with Honduras is emblematic of its shifting position within the international community, as an imperial presence, establishing and expanding industries in the less developed country at the expense of local citizens and the environment.

Canadian economic and political ties with Honduras intensified following Hurricane Mitch. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch ravaged much of Central America and resulted in the deaths of over 11,000 people.[1] It also left Honduras with $3 billion USD in damage from the catastrophe, causing utter economic devastation in one of the poorest countries in Latin America.

Following the hurricane, Ottawa responded with a “long-term development plan,” offering the Honduran government $100 million USD over four years for reconstruction projects. Part of this proposal included the introduction of forty Canadian companies into Honduras for investment purposes, which provided them with the opportunity to claim Honduran land and mineral assets. Canadian and U.S. developers helped rewrite the Honduran General Mining Law, and created the National Association of Metal Mining of Honduras (ANAMINH) to advance their interests in the nation. Under the new law, foreign mining companies have the right to subsurface land rights and tax breaks, marking a sharp change from the mining laws of the colonial era.[2]

Not surprisingly, mining—bolstered by foreign capital—has grown to be the dominant industry in Honduras. Foreign mining companies have done well under the new laws, with the Honduran government granting approximately 30 percent of Honduran territory in mining concessions.2 These companies, now owning a substantial portion of Honduran land, have a vested interest in the country’s politics. This is particularly true for Canadian mining corporations, which dominate the Honduran mining sector. According to the president of the ANAMINH, 90 percent of foreign mining investments in Honduras are Canadian.[3]

The Coup

Canadian mining corporations have a deep-rooted interest in keeping Honduran regulatory mining laws weak. These interests were threatened, however, when left-of-center candidate Manuel Zelaya was elected in 2006. Shortly after taking office, Zelaya announced his plans to reform the mining sector by restricting foreign mining companies in Honduras, distinguishing himself as a leader of an anti-foreign mining viewpoint. In May 2009, only a month before the armed forces ousted Zelaya, the Honduran Congress drafted a new mining bill. The bill was set to increase taxes on foreign mining companies, prohibit open-pit mining, and outlaw the use of toxic substances in mining activities. The bill would have required approval from local communities before mining operations went forward. However, Zelaya was forcefully removed from power on June 28, ending all discussion of mining reform.[4]

A Pointed Silence

After the coup, nearly every country denounced the removal of the democratically elected president. However, Ottawa remained silent and the Canadian media hardly reported on the political crisis.[5] According to Professor Tyler Shipley at York University in Toronto, Canadian reporters waited over twenty-four hours to report on the issue, even as international media immediately flooded into Honduras to report on the coup. When the Organization of American States (OAS) met to discuss the issue in July of 2009, Canada stood out again for its asymmetrical relationship with Honduras. Although most countries favored the return of Zelaya and the implementation of sanctions against the coup government, Canada argued that the international community had no grounds to intervene. Peter Kent, a minister of state for the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, wanted to restore democratic order with Honduras’ interim government and strongly opposed Zelaya’s return. In contrast, the U.S. ambassador claimed that the U.S. government would most likely move to suspend economic development and military assistance to Honduras.[6] However, behind the scenes, U.S. support for the coup government was key in keeping the new regime in power. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton went as far as to criticize Zelaya for wanting to return to his own country, calling it “reckless.”[7] Nevertheless, Canada declined to condemn the coup and publicly supported the status quo, while most of the international community rejected the coup government.

Illegitimate Democracy

In November 2009, the Honduran government held its scheduled elections. However, only the United States, Colombia, Costa Rica and Canada argued that the elections were fully democratic.[8] Most nations dismissed the elections as an obvious attempt to retroactively provide legitimacy to the coup government. In the eyes of many onlookers, the elections left much to be desired in terms of legitimate electoral participation.

One of the major flaws of the election was the pressure placed on the political opposition. The coup government accomplished this through mass arrests, illegal detentions, and violence. International human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (at the OAS) thoroughly documented these violations.[9]

In response to this widespread repression, more than 50 candidates for public office, including one would-be presidential candidate, removed their names from the ballot in protest against the interim government. Meanwhile, the coup government compiled the names of anti-coup activists and gave them to the military, which then threatened these leaders, making it difficult for protesters to unite against the fraudulent election.[10] Due to the lack of progressive candidates and political coercion, only 35 percent of the population voted, and 70 percent of voters were from Honduras’ wealthy neighborhoods.[11] This was not an election in which the poor were invited. In short, the election that brought President Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo to power was far from democratic; nevertheless, countries such as Canada and the United States endorsed it.

Lie and Reconciliation Commission

After the coup and the fraudulent election, a dispirited Honduran society scrambled to return to normalcy. One of the primary ways Canada sought to help Honduras return to business as usual under the new government was by offering to help create a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The role of this commission was to investigate events surrounding the coup.

Shortly after President Lobo created the commission, Canada supplied funding and nominated Michael Kergin to be a commission member. Kergin had been a Canadian diplomat and employee of Bennett Jones, a Canadian corporate law firm that specializes in investment law and mining.[12] In spite of Canadian support, the commission was not recognized by any social or human rights organization that had spoken out against the military coup. Furthermore, the commission failed to consult the family members of victims that were tortured, murdered, and repressed by the post-coup government. [13] Therefore, the commission claimed to validate the post coup government without consulting the necessary parties.

Readmission into the OAS

Immediately following President Lobo’s inauguration on January 27, 2010, Peter Kent announced his support of the Lobo administration’s initiative to reintegrate the country into the international community, particularly into the OAS. Kent met with OAS Secretary General José Miguel Insulza on February 16 of that year to push the Canadian government’s goal of reinstating Honduras into the OAS. [14] After the OAS accepted Lobo’s administration, Canada further solidified its role as the government’s protector. In 2011, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper became the first foreign leader since Lobo’s inauguration to visit Honduras and meet with the President.[15]

Industrial Abuses

Critics have long held that Canadian involvement and investment in Honduras is plagued with corruption, and that the situation has only worsened since the coup. In particular, many criticize the manufacturing sector, which is Honduras’ second largest industry, for mistreating its workers. One of the industry’s worst offenders is Gildan Active Wear Inc., a Montreal-based textile manufacturer that laid off hundreds of Canadian workers in order to facilitate its move to Honduras in 2007. Gildan Active Wear Inc. is one of three dominant, low-wage sweatshop companies operating in Honduras. The company’s stated goal for the relocation was to improve its competitiveness and efficiency.[16]However, there is a darker side to its operations in Honduras. Many women working in Canadian-owned sweatshops have reported serious injuries caused by repetitive work in the factories. These injuries include musculo-skeletal problems and injuries sustained from major accidents, and they often leave women unable to work. Still, female workers must continue to feed and clothe their families while paying costly medical bills. According to Karen Spring with Rights Action, Gildan is aware of these atrocities; it has refused to provide compensation.[17] The company has also been accused of firing workers for attempting to unionize.[18][19]

Exploitive Tourism

Similarly, many criticize Canadian investment in Honduras’ tourism industry for its impact on the local population. One of the industry’s leading promoters is Randy Jorgensen, who is also the president of the Canadian pornography chain Adults Only Video and the owner of the real estate development company Life Vision Properties, based in Trujillo, Honduras. In 2007, Jorgensen and some local intermediaries purchased property illegally in the Bay of Trujillo, resulting in the expulsion of an Afro-Indigenous community known as the Garífunas from the region. Jorgensen has also acquired Garífuna land in other Honduran towns such as Santa Fe, San Antonio, and Guadalupe. Prior to the 2009 coup, local inhabitants had lodged formal complaints about these fraudulent purchases, but government authorities failed to intervene. Jorgensen used the chaos and the political instability during the coup to acquire environmental permits to construct villas on the hillsides overlooking the Caribbean in the protected area of Capiro and Calentura National Park. In spite of these offenses, Ramon Lobo Sosa, President Lobo’s brother, strongly supported Jorgensen. In 2011, Lobo himself praised the businessman in a cabinet session. To make matters worse, Jorgensen receives financial support from the Canadian Shield Fund, which itself receives funding from controversial mining companies Barrick Gold and the Canadian Oil and Gas Company. [20] These economic earnings come at the expense of factory workers and local inhabitants. Canadian investment in Honduras operates without restraint, and the industry’s ability to manipulate the Honduran economy and its local population only increases with time.

Free Trade Agreement

Once the chaos surrounding the coup quieted down, Canada made quick use of its newfound political capital and began discussing a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Honduran government. The Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement was signed into law on November 5, 2013, along with parallel labor and environmental cooperation agreements.[21] By June 2014, the Canada-Honduras Economic Growth and Prosperity Act—designed to implement the Free Trade Agreement—received royal acceptance. [22] According to the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development, “The Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement includes provisions on market access for goods, services (including financial services), investment and government procurement. Once the agreement is fully implemented, over 98 percent of tariff lines will be duty-free.”[23]

The free trade agreement is meant to create transparency and promote a rules-based commercial and investment environment. However, the Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement is a flawed agreement, benefiting only foreign corporations and those that support them, much like other FTAs in Latin America. For example, Gildan Activewear Inc. recently closed its last North American factory in Alabama as a result of the agreement and announced that it would be investing 100 million dollars into a new sock factory in Honduras.[24]

The corporation will increase investment and hire additional workers in Honduras, despite its failures to properly provide for its current employees. The agreement will lower taxes for Canadian corporations and encourage further investment, thereby increasing their power and influence in Honduras. Canadian companies are bound to benefit from the agreement while the Honduran population continues to suffer environmental and human rights abuses.

Expansion of the Oil Industry

Canadian investment and influence has expanded since the FTA was signed, as shown by Canada’s growing interest in oil development in the country. The Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development has been financing technical assistance to the hydrocarbon sector in Honduras as part of a larger project managed by the Latin American Energy Organization. The Canadian International Development Agency originally approved the project to set out a five-year plan that would start by reviewing the country’s oil and gas potential. Initial tests revealed that the land with the most hydrocarbon potential was offshore, in the inland region along the Caribbean coast, and in the Moskitia, a remote region in the northeast with a large indigenous population.[25]

Some indigenous organizations have voiced their opposition to expanding oil and gas activity in Honduras. A closer examination of the history of extractive industries in the region causes the indigenous communities to suspect that these industries will only benefit transnational corporations at the expense of local communities.[26] However, Canadian corporations now hold considerable political and economic clout in Honduras and will most likely profit off of these social losses.

The New Imperialism

Canada’s increasing dominance over Honduras is indicative of its shifting imperial role in Latin America and the international arena. Over time, Canada has increased its influence through subtle diplomatic and economic manipulations in Honduras. These political maneuvers include Canada’s response to the 2009 coup, its recently enacted free trade agreement, its manufacturers’ abuses, and its dangerous policies with regard to oil. Unlike the outright militant actions pursued by other superpowers in Latin America over the past century, Canada has increased its hold on Honduras without impactful restrictions on its industries in Honduras. Thus, Canadian relations with Honduras demonstrate a new, subtle, and insidious imperialism.

Special Thanks to Professor Tyler Shipley, York University Toronto, Ontario

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

References

[1] “Mitch: The Deadliest Atlantic Hurricane Since 1780,” National Climatic Data Center, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/reports/mitch/mitch.html

[2] Ashley Holly, “Shame on Canada, Coup Supporter,” The Tyee, July 9, 2009, accessed July 16, 2014, http://thetyee.ca/Views/2009/07/09/ShameOnCanada/

[3] Todd Gordon, “Military Coups are Good for Canadian Business: The Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement,” Global Research, March 3, 2011, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.globalresearch.ca/military-coups-are-good-for-canadian-business-the-canada-honduras-free-trade-agreement/23492

[4] Jennifer Moore, “Canada’s Subsidies to the Mining Industry Don’t Stop at Aid: Political Support Betrays Government Claims of Corporate Social Responsibility,” MiningWatch Canada, June 2012, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.miningwatch.ca/sites/www.miningwatch.ca/files/Canada_and_Honduras_mining_law-June%202012.pdf

[5] Dawn Paley, “Canada, Honduras and the Coup d’Etat,” The Dominion, January 8, 2010, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.dominionpaper.ca/articles/3080

[6] Ginger Thompson and Marc Lacey, “O.A.S. Votes to Suspend Honduras Over Coup,” The New York Times, July 4, 2009, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/05/world/americas/05honduras.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[7] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-zuesse/hillary-clintons-two-fore_1_b_3714765.html

[8] “Nations Divided on Recognizing Honduran President-Elect,” CNN World, November 30, 2009, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/americas/11/30/honduras.elections/index.html?iref=24hours

[9] http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2009/11/25/the_sham_elections_in_honduras

[10] ibid

[11] Rory Carroll, “Honduras Elects Porfirio Lobo as New President,” The Guardian, November 30, 2009, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/30/honduras-lobo-president

[12] Todd Gordon, “Military Coups are Good for Canadian Business: The Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement,” Global Research, March 3, 2011, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.globalresearch.ca/military-coups-are-good-for-canadian-business-the-canada-honduras-free-trade-agreement/23492

[14] .( http://www.counterpunch.org/2010/03/19/canada-s-long-embrace-of-the-honduran-dictatorship/

[15] Todd Gordon, “Canada Backs Profit, Not Human Rights, in Honduras,” The Star, August 2, 2011, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.thestar.com/opinion/editorialopinion/2011/08/16/canada_backs_profits_not_human_rights_in_honduras.html

[16] “Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement Will Deepen Conflict,” The Council of Canadians, February 13, 2014, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.canadians.org/blog/canada-honduras-free-trade-agreement-will-deepen-conflict

[18] “Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement Will Deepen Conflict,” The Council of Canadians, February 13, 2014, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.canadians.org/blog/canada-honduras-free-trade-agreement-will-deepen-conflict

[19] Adrienne Pine, “Sweatshops, Mining, Tourism & “Free” Trade Negotiations,” Quotha, January 13, 2011, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.quotha.net/node/1468

[21] “Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement,” Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, June 26, 2014, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/honduras/index.aspx?lang=eng

[22] “Canada-Honduras Economic Growth and Prosperity Act Receives Royal Assent,” Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, June 19, 2014, accessed July 16, 2014, http://www.international.gc.ca/media/comm/news-communiques/2014/06/19a.aspx?lang=eng

[23] Ibid.

[25] Sandra Cuffe, “Canadian Aid, Honduran Oil,” Upside Down World, March 24, 2014, accessed July 16, 2014, http://upsidedownworld.org/main/news-briefs-archives-68/4759-canadian-aid-honduran-oil

[26] (http://www.breakingthesilenceblog.com/general/the-media-coop-canadian-aid-honduran-oil-ottawa-funds-set-to-encourage-oil-investment/)