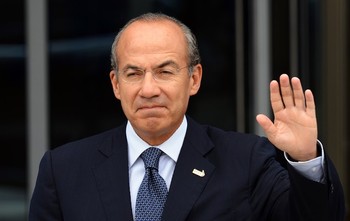

Calderón Bids Farewell: A COHA Side-By-Side Report with The Pan-American Post

COHA’s Take on Calderón’s Legacy

Mexican President Felipe Calderón’s monumental six-year term will come to an end on November 30. His presidency was categorized by a crackdown on organized crime and a predictable surge of violence that at one time threatened Mexico’s internal security. During this time, Calderón’s hard-lined approach to organized crime sparked a backlash among the Mexican cartels resulting in as many as 60,000 drug-related deaths and often searing international criticism. On the other hand, he caused grave harm to the cartels operating within Mexico’s borders. If there is one lesson we can learn from the past, it is that political figures tend to be remembered more favorably after they are distantly gone. Therefore it might be prevalent to ask the question, how will Calderón’s legacy be remembered?

Calderón’s stepped up pursuit of Mexican drug cartels increased violence in a variety of ways. To combat the cartels’ hold on Mexico, Calderón deployed 50,000 military troops in an attempt to subdue the violence.[1] However, this created an internal war that jeopardized the security of the Mexican people. Furthermore, Calderón can still be blamed for inadequatley addressing the ever-present theme of corruption within the Mexican government and security forces. Critics suggest this may have been a vital factor in the continuation of the drug cartels’ success.

Although, it would be far from just to conclude that Calderón ’s pursuit of organized crime was entirely unsuccessful:

The drug war did have some successes, taking down many of the country’s biggest crime lords. With the death of Zetas boss Heriberto Lazcano in October, Calderón pointed out that the government had captured or killed 25 on a list of 37 cartel leaders which it published early in his term.[2]

Furthermore, during Calderón’s presidency the Mexican government has seized over 114 tons of cocaine, 11,000 tons of marijuana, 75 tons of methamphetamines, 100,000 drug-associated vehicles, and $1 billion USD in cash. These figures represent a cost to the cartels equaling at least $14.4 billion USD.[3] The aforementioned increase in seizures represents an admirable attempt by the president to challenge a dangerous status quo that only worsened year after year.

Additionally, the dominant role that U.S. drug consumption has played in the rise of the ongoing drug cartel violence should not be ignored. Mexican cartels have become the primary supplier of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines to the United States. Along with being the number one importer of Mexican drugs, the United States has played a primary role in supplying the cartels with weapons and ammunition. According to Mexican Ambassador Arturo Sarukhan, between 2007 and 2010, “the number of weapons seized by Mexican officials with U.S. origins surged by 225 percent.”[4] These astonishing factors demonstrate the crucial role that the United States has played in the rise of the drug cartels’ power during Calderón ’s presidency. In any case, while outgoing president Felipe Calderón himself has stated that it is “impossible” to stop the drug trade, it is important to remember the substantial steps he took to weaken organized crime, along with the role the United States has played in assisting the cartels. With this in mind, it is likely that the current unpopular perception will not be Felipe Calderón’s lasting legacy.

Gene Bolton and Ethan Roseman, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated

[1] Hannah Stone, Assessing Calderon’s Presidency on his Last Day in Power, The Pan-American Post, November 30, 12.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Calderon defends war on Mexican drug cartels,” The Telegraph, September 2, 2012, accessed September 13, 2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/mexico/9515781/Calderon-defends-war-on-Mexican-drug-cartels.html.

[4] Arturo Sarukhan referenced in Janell Ross, Mexico Ambassador Arturo Sarukhan Says U.S. Guns Fuel Violence, Denies Mexico Is Infringing Upon Gun Rights,” The Huffington Post, June 1, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/06/01/mexico-guns-arturo-sarukhan-us-weapons-mexico-violence-gun-rights_n_1563250.html.

The Pan-American Post: Assessing Calderon’s Presidency on his Last Day in Power

Mexican President Felipe Calderon prepares to leave office tomorrow after six years in which he battled drug cartels, unleashing a tide of violence which may only now be on the point of receding.

His presidency was defined above all by security, as he launched a head-on attack on the organized criminal groups that had been able to operate relatively unmolested under his predecessors. Calderon sent more than 50,000 troops onto the streets of Mexico to fight drug gangs, starting in his first month in office. The resulting violence left some 60,000 dead in killings linked to the drug war, with an estimated total of 101,000 murders during his term, about a third higher than in the previous administration, reports the Associated Press. InSight Crime quotes official statistics which show that the number of murders nearly doubled from 10,300 in 2007, Calderon’s first year in power, to 22,500 this year.

The real figure may be even higher, as some 25,000 people have gone missing in the last six years, according to figures from Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office, as the Washington Post reports.

The drug war did have some successes, taking down many of the country’s biggest crime lords. With the death of Zetas boss Heriberto Lazcano in October, Calderon pointed out that the government had captured or killed 25 on a list of 37 cartel leaders which it published early in his term. A notable absence is Sinaloa Cartel leader Joaquin Guzman, alias “El Chapo,” perhaps the world’s biggest trafficker, who remains at liberty as Calderon leaves power.

The chaos and violence has failed to have a significant impact on the supply of drugs passing through Mexico to the US, and decapitated criminal groups have splintered to from a larger number of smaller and often more aggressive organizations.

Incoming President Enrique Peña Nieto is expected to take a different tack in fighting cartels, focusing not on pursuing capos or intercepting drugs but on bringing down the levels of violence.

There are signs that the tide may be starting to turn, and that the violence may be slowing. Places like Ciudad Juarez, the most dangerous city in the world at one point in Calderon’s presidency, have seen a dramatic security improvement in the last year and a half. Security analyst Alejandro Hope, who closely follows the phenomenon, wrote recently that 2012 was on course to be the first year to see an annual drop in homicides since 2007, while reports of large-scale massacres and dismembered bodies seemed to have slowed. If his analysis is correct and the turning point has already been reached, then Peña Nieto will be the one to reap most of the political benefits.

InSight Crime’s Patrick Corcoran points to some errors of the Calderon era that Peña Nieto should avoid, including showy efforts to reorganize government institutions or create new police bodies which are “typically little more than a distraction; the efforts needed to pass legislation and then create the new force would be better spent investing in the existing police bodies and addressing their specific shortcomings.” The new president has revealed plans for a security force modeled on the French National Gendarmerie, and to disband the Security Ministry, putting police and security bodies under the control of the Interior Ministry. The Miami Herald points to possible risks of this, noting that the Interior Ministry was long used by Peña Nieto’s PRI party “to co-opt or pressure opponents, rig elections and strong-arm the media.”

For Corcoran, however, “many of Calderon’s initiatives were philosophically sound, and simply require more patience or persistence,” including police vetting, targeting kingpins, and justice reform.

The reforms to justice institutions in particular have not been carried out in full, with the oral trial system still mostly unimplemented four years after it was approved, as the AP comments. And, as the Washington Post notes, “not one of the dozen top cartel leaders captured alive has been put on trial and convicted in Mexico using police-gathered evidence or witness testimony,” pointing to deep weaknesses in the justice system.

Calderon had more success when it comes to the economy. The AP sums up his term as having saved Mexico from collapsing during the global financial crisis by ensuring fiscal stability, though it left the country with no improvement to poverty levels, and insufficient job growth. Calderon saw out his term by passing a labor reform law on Thursday.

Peña Nieto is promising to bring in free market reforms, including opening up the state-run oil industry.

For the Washington Post, during Calderon’s term, “modest gains were made, but his center-right government was consumed by the drug war,” which has now reached a stalemate.

The LA Times highlights Calderon’s openness to cooperation with the US, saying that he “essentially rewrote the rules under which foreign forces could act here in matters of national security.”

Now, Calderon is planning to go to Harvard University as the first Angelopoulos Global Public Leaders fellow at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, as the New York Times reports, following a tradition of ex-presidents leaving the country.

The analysis was prepared by Hannah Stone of the Pan-American American Post. Hannah Stone is also a research fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.