Brazilian Intervention in Regional War on Drugs at Stake

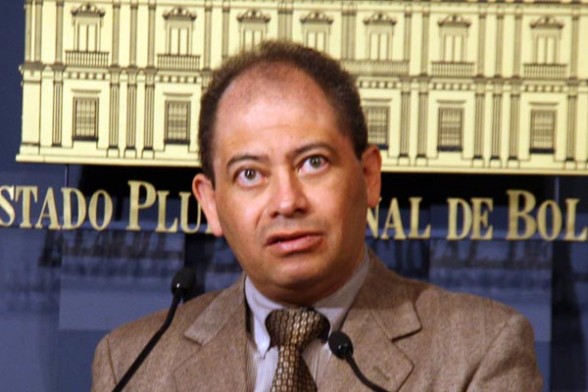

On August 23, Bolivia’s minister of government, Carlos Romero, reaffirmed his opposition to the Brazilian Federal Police’s intervention in the narcotics trade on Bolivian soil. Reacting to an article published on August 20 in the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo depicting Brazil’s new vigorous and interventionist antidrug policy, Mr. Romero asserted that the Fuerza de Tarea Conjunta, the Bolivian army corps dedicated to combat the illegal coca production, was the sole agency competent and qualified to face down cocaine trafficking in the Bolivian context.”[1] The Bolivian position has become increasingly influenced by the country’s recent success in the destruction of illegal coca fields.[2] With this declaration, Bolivia has become the first South American nation to stand up to Brasilia’s growing role in patrolling trafficking along its border regions.

On August 20 César Guedes, representative for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in Bolivia, called upon La Paz to accept foreign help to abate narco-trafficking, alluding to the Brazilian Federal Police forces.[3] Mr. Guedes inferred that Bolivia not only grows and distributes coca leaves but also currently serves as a major transiting route for cocaine due, to its geographical position astride the so-called Andean Route. Mr. Romero says this route is of major concern for Brazil.[4] This role places Bolivia at the center of the questions surrounding the production of illegal drugs in the region, as it becomes increasingly clear that the country cannot solve drug trafficking alone. Even as Bolivia argues that there is still no need for U.N.-backed Brazilian interference, La Paz has also called for a renewal of the cooperation described in the tripartite agreement signed on January 20 between Bolivia, Brazil and the U.S. This agreement supports technological assistance by Brazil and the U.S. in destroying illegal coca fields in Bolivia, but does not officially address the issue of Bolivia as a trafficking route.

La Paz’s reluctance to allow Brazilian interventionism can be explained by the differing acceptance of the culture of coca among Brazil’s other neighbors. Unequivocally, La Paz’s nationalistic attitude toward coca associates the cultivation and mastication of coca as a societal pillar of Bolivian cultural identity. Thus, former cocalero syndicalist and current President of Bolivia Evo Morales instituted a domestic policy legitimizing many coca producers as well as authoring the slogan “Coca Yes, Cocaine No,” which directly opposed the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) strategies in the region.[5] This policy is drastically different from Brazil’s other Amazonian neighbors, many of whom have recently authorized Brasilia to undergo small operations on their soils. Notably, Peru has permitted the Brazilian Federal Police to lead coca field eradication operations on its soil, in response to the increasing cocaine production along the Brazilian border.[6] This scenario fits within Brasilia’s broader plan of investing in efforts to close its frontiers to the drug trade by exercising its new ability to take control of these previously ungoverned regions. Last year, Brazilian forces executed the “Operação trapézio Amazônico,” an operation to destroy the intense drug trafficking in the border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Peru.[7] Currently, Brazil is partaking in another military operation, the Operation Agata 5, near the southern and southeastern borders, representing a massive attempt to control the notoriously porous Tri-Border Area.[8] Brasilia previously declared a desire to close this border with Paraguay after reports of cartels moving into Brazilian territory surfaced last year.

On one hand, Brasilia’s strong urge to secure its borders could appear to be a form of expansionism from the perspective of its neighbors, who reject Brazilian presence on their soil. In these often-lawless regions, countries fear Brazil’s growing influence at the expense of their own sovereignty. On the other hand, Brazilian interventionism could also be interpreted as a sign of clear-sighted pragmatism aimed at assuming a regional security role while simultaneously solving its domestic problems. Indeed, 54 percent of cocaine consumed in Brazil is trafficked through Bolivia—60 percent of which is grown in Peru.[9] Indeed, Brasilia has acknowledged that its forces are more capable of combating the drug problem existing along its borders than those in Peru or Bolivia. Thus, Brasilia is actively attempting to protect its own territory from an external direct threat, while at the same time observing that the Amazonian borders are not effective barriers to illicit trade. This increased patrolling activity also signals that Brazil has started to supplant the United States, following the region’s new rejection of the failed “War on Drugs,” and that Brasilia has inherited the role of regional overseer once held by Washington. Brasilia’s assertive border policy today symbolizes the new efforts to fight drug trafficking instead of fighting consumption, and has taken on new treaties utilizing new weapons and strategies.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

[1] “Bolivia tiene en su territorio más droga de la que produce” Correo del Sur. Sucre, August 23, 2012. http://correodelsur.com/2012/08/23/39.php

[2] “Gobierno descarta diálogo con cocaleros en Yungas de Vandiola”, Opinión. Cochabamba, August 23, 2012.

http://www.opinion.com.bo/opinion/articulos/2012/0823/noticias.php?id=68949

[3] “En Bolivia hay más droga de la que el país produce”, Opinión. La Paz, August 23, 2012. http://www.opinion.com.bo/opinion/articulos/2012/0823/noticias.php?id=68906

[4] Ibid.

[5] Relea, Francesca. “Cocaine and coca not the same thing, says Bolivia’s Morales in defiance of US”, El Pais. La Paz, July 5, 2012. http://elpais.com/elpais/2012/07/05/inenglish/1341492506_304424.html

[6] Mello Fernando, Neves Marcia. “PF avança a fronteira para combater tráfico de drogas”, Folha de São Paulo. Brasilia, August 20, 2012. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/1139987-pf-avanca-a-fronteira-para-combater-trafico-de-drogas.shtml

[7] “Mega operação antidrogas é lançada na tríplice fronteira Peru-Colômbia-Brasil”. Federal Public Ministry, general public prosecutor of the Republic, Assessor of the International Juridical Cooperation, July 7, 2012. http://ccji.pgr.mpf.gov.br/informes-internacionais/mega-operacao-antidrogas-e-lancada-na-triplice-fronteira-peru-colombia-brasil/

[8] Chief of the Comando da Area de Operações Prata, “Operação Agata 5”. Brazilian Ministry of Defense, http://www.operacoes.defesa.mil.br/a-operacao

[9] “Bolívia não aceita PF brasileira para destruir plantios de coca”, Folha de São Paulo. São Paulo, August 23, 2012. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/1141750-bolivia-nao-aceita-pf-brasileira-para-destruir-plantios-de-coca.shtml and “Bolivia descarta que la policia de Brasil ayude a erradicar los cultivos de coca”, La Prensa Latina. La Paz, August 23, 2012. http://laprensalatina.com/bolivia-descarta-que-la-policia-de-brasil-ayude-a-erradicar-los-cultivos-de-coca/