Alliance for Prosperity Plan in the Northern Triangle: Not A Likely Final Solution for the Central American Migration Crisis

By Mercedes Garcia, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

In the last three months of 2015, the United States faced another wave of immigration coming from the Northern Triangle (comprised by Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) that only further increased the severity of the child migration crisis that began in 2014. At the end of 2015, the U.S. had detained 21,469 migrants at the U.S. border.[1] This event, as well as U.S. Congress’ decision to allocate $750 million USD to Central America through the Alliance for Prosperity Plan, gave fresh fuel to those who oppose U.S. engagement and financial assistance in the region. Several experts and civil society organizations have expressed their opposition to the Alliance for Prosperity Plan, convinced that it will leave some people in those countries considerably worse off than they are now.[2]

The Alliance for Prosperity Plan is the response to the humanitarian migratory crisis that ushered in an influx of more than 40,000 unaccompanied children from the Northern Triangle to the U.S.’ southern border in 2014. The plan is a five-year initiative that intends to reduce Central Americans’ incentives to migrate; it differs from other U.S.-favored strategies in the region by focusing primarily on addressing the push/pull structural factors that have driven the recent exodus across the border instead of centering on containment and security initiatives. This shift of priorities is, undoubtedly, an improvement on the United States’ side.[3] However, Council on Hemispheric Affairs’ (COHA) analysts, as well as a variety of other experts, such as specialist Alexander Main, from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, agree that the plan fails to address the underlying issues of poverty and violence that conducted these waves of migration.[4] If the Alliance for Prosperity Plan is implemented as structured, it could end up harming, rather than aiding, Central Americans in the long-term.

The plan is worrisome in three main dimensions: the emphasis on attracting foreign investment, the support it provides for the continuation of dubious security initiatives, and the Central American governments’ lack of accountability. Although the plan contains stipulations to promote growth, a number of Central American leaders are highly concerned that the “Alliance for Prosperity” will become an opportunity for U.S. companies to further exploit the region, a thesis supported by Naome Klein’s book, The Shock Doctrine.[5] In terms of security, human rights organizations have expressed their concern for the sharp increase in U.S. military and police assistance assigned to the Northern Triangle since the mid-2000s. They fear that the continued support for the current security strategy known as the Central American Region Security Initiative (CARSI), will aggravate violence given that U.S. military assistance tends to coincide with higher levels of violence in the region.[6] While the plan lays down prerequisites in regards to governance and respect of human rights, Annie Bird, former guest scholar at COHA, explained that “the conditioning language is vague…the final legislation calls for ‘cooperation’ with regional human rights entities. This will allow the State Department a lot of room to claim that governments are complying, even when they aren’t.”[7] The Alliance for Prosperity Plan is an initiative that could be promising but requires improvement, as there are meaningful features in the package that will do little to halt migration. The United States may need to rethink its foreign policy before it does — yet more — damage to Central American nations.

What is the Alliance for Prosperity Plan in the Northern Triangle?

The Alliance for Prosperity Plan is the result of a joint proposal from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the United States that intends to address the structural issues — such as poverty and violence — that led to the mass flight of unaccompanied children to the United States.[8] The proposal was initially drafted by the three Central American governments at the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). President Obama decided to join the deliberations in early 2015; by February 2, 2015, he already had requested funding for the plan from U.S. Congress.[9]

The proposal contains four strategic lines of action: stimulating the productive sector to create economic opportunities, developing growth opportunities, improving public safety and enhancing access to legal systems, as well as strengthening institutions to increase people’s trust in the state. By following such a strategic approach, the plan intends to revitalize the economy and foster prosperity in the region by creating a good climate for business development. Major steps to implement this strategy include attracting private investment, pushing for large-scale infrastructure modernization projects, reducing energy costs, as well as promoting strategic sectors such as textile, light manufacturing, tourism, and agro-industries. Other measures include strengthening security, boosting the development of human capital, promoting violence prevention programs, strengthening public institutions, and increasing transparency.[10]

The United States plays a key role in financing the program, on December 18, 2015, the U.S. Congress approved the appropriation of $750 million USD in assistance funds for Central America. Although the Central American leaders’ proposal requested $1 billion USD, the funding represents a dramatic increase compared to assistance given to the region in other years. In Fiscal Year 2015, the U.S. Congress allocated $560 million USD, while in 2014 it only allotted $305 million USD.

According to the White House Fact Sheet, in the 2016 Fiscal Year, the U.S. split the $750 million USD budget for the Northern Triangle into the following categories: $299 million USD for development assistance; more than $200 million USD for security; $184 million USD for economic prosperity programs; $26 million USD towards military initiatives; and $4 million USD to global health, military training, and other regional prosperity programs.[11] In order to receive such funds, the Northern Triangle countries have to abide by a set of governance and human rights conditions laid out by U.S. Congress, as cited in previous COHA reports.[12]

Neoliberal Policies?

The Alliance for Prosperity Plan’s emphasis on neoliberal policies is concerning for opposition groups. The first strategic line of the plan stresses the promotion of infrastructure projects and foreign investment as opposed to the development of social inclusion programs. Civil society organizations leaders, such as Alexis Stoumbelis, the Executive Director of CISPES, doubts that the “trans-generational” threat of rampant violence and poverty will be diminished without an appropriate use of foreign aid.[13]

Oscar Chacón, the Executive Director of Alianza Americas, an influential coalition of U.S.-based Latin American migrant organizations, highlights the need to implement social programs. In an interview with the author, Mr. Chacón pointed out three key areas of transformation (education, health, and tax laws) that the Alliance for Prosperity Plan barely addresses. He stated that “the Alliance for Prosperity Plan is an initial step going in the right direction, but definitely insufficient and it needs to be expanded.”[14][15] He argued that a strategy with such ambitions—alleviating poverty and preventing migration—requires a different focus and a projection of at least 15 to 20 years in order to yield sustainable and long-term effects.[16]

Along the lines of “stimulating the productive sector”, the Alliance for Prosperity development package stipulates easing the entrance of foreign investment, potentially welcoming U.S. corporations to the Northern Triangle. This happens, as Alexander Main states, “generally through the promotion of poorly regulated exploitation of local natural resources,” and “often at the expense of the environment and the rights of local communities and maquila-type assembly and garment industries, which generate unstable jobs with poverty wages.”[17] This is perfectly exemplified by the negative effects of the widely known case of the United Fruit Company early in the 20th century, the presence of Monsanto in the beginning of the mid-2000s, and the implementation of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) in the region in 2005.[18]

And Security?

Although the largest proportion of aid in the Alliance of Prosperity Plan is allocated for development initiatives, the fact that the United States continues to fund initiatives such as CARSI sets alarms off among opposition groups. The United States will allocate $348.5 million USD, roughly 46 percent of total Alliance for Prosperity funding to CARSI; which has been widely criticized for the militarization of security and its murky mechanisms of multilateral cooperation and unclear—and sometimes detrimental— results.[19] CARSI derives from the Merida Initiative, which was initially designed to help local governments to combat drug trafficking in Mexico and Central America by working on institution building, rule of law activities, and maritime security among other initiatives.[20] By 2010, the Central American dimension of Plan Merida morphed into what is now CARSI. The new strategy pledged to:

“Create safe streets for the citizens in the region; disrupt the movement of criminals and contraband within and between Central America; support the development of strong accountable Central American governments; re-establish effective state presence and security in communities at risk; and foster enhanced levels of security and rule of law coordination and cooperation between the nations of the region”[21]

However, the dynamics of Merida’s Initiative and, consequently, CARSI, have coincided with the militarization of the fight against organized crime. In fact, since these initiatives were implemented, Mexico and the Northern Triangle have experienced historic levels of violence.[22] According to the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars’ working papers on CARSI, human rights abuses by military officials in the service of Northern Triangle countries have become more frequent since the regional security initiative was inaugurated.[23] According to InSight Crime, a leading NGO reporting on crime and security issues in Latin America, in cases like El Salvador’s, extrajudicial killings continue to be alarmingly regular.[24] Not surprisingly, the Wilson Center has affirmed that CARSI “does not reflect an integrated strategy for addressing the critical security threats in Central America and thus has had negligible impact on the factors driving the increased Central American migration since 2011.”[25] Furthermore, CARSI’s funding comes from several sources, mainly the U.S. Agency for International Development, the State Department’s Bureau of the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement’s Affairs, and the Economic Support Fund.[26] The fact that the multiple U.S. funders need to collaborate with several local Northern Triangle governments makes it difficult to accurately track where and how agencies’ funds are used. This opaque operating mechanism leaves ample room for skepticism, as Mr. Main argued in his article “Will Biden’s Billion Dollar Plan Help Central America?”[27] This brings us to the third reason for concern: namely, the lack of democratic accountability in the three receipt countries.

Accountability in the Northern Triangle?

Countries in the Northern Triangle are notable for their prevalence of corruption, human right abuses, and high levels of impunity. These are states where 95 percent of crimes go unpunished.[28] Strengthening the rule of law is a challenge that requires social and cultural transformations that are unlikely to transpire in the near future. In this sense, even if the delineated conditions to receive aid are followed precisely, nothing guarantees that these problems will not constitute a genuine threat in the future. Although there are recent signs of improvement from all countries in the Northern Triangle in their fight against corruption and impunity, there is still room for skepticism, as changes made in current administrations may not be extended to the following ones.

El Salvador will institute an Anti-Corruption Program in conjunction with the United Nations Office of Drug and Crime (UNODC).[29] Guatemala’s campaign against corruption kicked off with the arrest of Antigua’s, Guatemala second-largest city, mayor and several other local officials.[30] Meanwhile, Honduras has announced the launch of its OAS-backed anti-corruption mission.[31] Although these changes are positively accepted, recipient countries are, very likely, driven by the urge to receive aid from the Alliance for Prosperity Plan. Thus, their commitments to improve their countries’ chaotic environments are to be taken cautiously. The conditions imposed by the State Department need to have a long-term outlook and be precisely met in order for aid to promote progress.

Conclusions

The Alliance for Prosperity Plan is too short-sighted in its aims to provide solutions for the most vulnerable parts of society; marginalized Central Americans will continue to migrate to the United Sates if the plan is not implemented adequately. Governments in the Northern Triangle need to make more efforts to protect the dignity and wellbeing of their citizens. The plan promises to promote prosperity in the region, which may happen in the short- and mid-term, but the long-term effects can be detrimental for impoverished communities. The plan’s emphasis on economic growth and the attraction of foreign investment rather than social progress is troubling; aid needs to be more focused on empowering individuals rather than creating precarious employment opportunities, like those offered to unskilled workers by most foreign corporations.

In terms of security assistance, CARSI’s multilateral mechanisms and undefined results leave a lot of room for skepticism. The United States needs to be more cautious in funding such type of initiatives; security assistance needs to be more integrated and restructured to yield convincing results.

Furthermore, the United States needs to be more prudent in recognizing that governments in the Northern Triangle have a long way to go in demonstrating their accountability and should stay firm on demanding transparency and strengthening institutions in the region. Not only does the United States need to ensure the proper use of funds, but only through a full commitment from Northern Triangle governments will the regional situation improve.

The U.S. response to poverty and violence in the Northern Triangle unquestionably stems from good intentions, but attempting to provide a solution with strategies that could end up being a reminder of past U.S. failures will exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, the mounting challenges faced by Central Americans in the long term.

By Mercedes Garcia, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

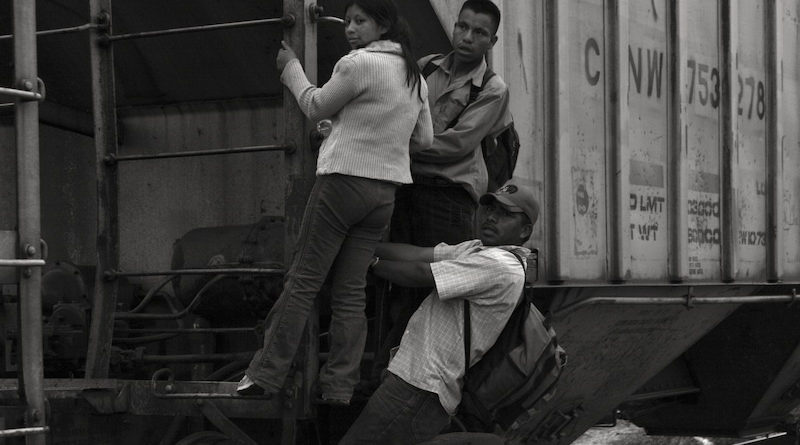

Featured Photo: Transient migrants from Central America making their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. Taken from Wikipedia.

[1] Lakhani, Nina. “Surge in Central American Migrants at US Border Threatens Repeat of 2014 Crisis.” The Guardian. January 13, 2016. Accessed February 03, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jan/13/central-american-migration-family-children-detention-at-us-border.

[2] http://cispes.org/article/special-report-congress-doubles-us-aid-central-america

[3] https://coha.org/2016-appropriation-bill-highlights-us-support-for-central-america-and-colombia/

[4] http://thinkprogress.org/immigration/2016/02/04/3745790/us-alliance-for-prosperity-money-central-america/

[5] http://www.powells.com/book/shock-doctrine-the-rise-of-disaster-capitalism-9780312427993; http://cispes.org/sites/default/files/wp-uploads/2015/04/Final-Letter-to-Presidents-at-Summit-of-the-Americas.pdf

[6] http://www.justassociates.org/sites/justassociates.org/files/eng_letter_to_heads_of_states_-_sica_april_30_2013.pdf

[7] “Special Report: Congress Doubles U.S. Aid to Central America” CIPES. January 12, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2016. http://cispes.org/article/special-report-congress-doubles-us-aid-central-america

[8] “Presidents of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras Outline Plan to Promote Peace and Prosperity in Their Region.” IDB. November 14, 2016. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://www.iadb.org/en/news/news-releases/2014-11-14/northern-triangle-presidents-present-development-plan,10987.html.

[9] Biden, Joseph R. “Joe Biden: A Plan for Central America.” The New York Times. January 29, 2015. Accessed February 2, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/30/opinion/joe-biden-a-plan-for-central-america.html?smid=pl-share.

[10]“Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle: A Road Map” prepared by the countries of the northern triangle. September, 2014. Accessed January 30, 2016. http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=39224238

[11] “Fact Sheet: United States and Central America: Honoring our Commitments”. The White House Office of the Press Secretary. January 14, 2016. Accessed January 28, 2016. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/01/15/fact-sheet-united-states-and-central-america-honoring-our-commitments

[12] Ibid; Baruh Santiago, and Miguel Salazar. “2016 Appropriation Bill Highlights US Support for Central America and Colombia.” COHA. December 21, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2016. https://coha.org/2016-appropriation-bill-highlights-us-support-for-central-america-and-colombia/.

[13] Yu-Hsi Lee, Esther. “Experts Say U.S. Aid Package To Central America Is Backfiring Big Time.” Think Progress RSS. February 04, 2016. Accessed February 23, 2016. http://thinkprogress.org/immigration/2016/02/04/3745790/us-alliance-for-prosperity-money-central-america/.

[14] Translated by the author. ¨…Este plan, la Alianza por la Prosperidad es un primer paso en la dirección correcta, pero definitivamente insuficiente y necesita ampliarse…¨.

[15] Interview with Mercedes Garcia February 3, 2016 at AFL-CIO press conference on the Central American Migration Crisis.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “U S Congress Approves Funds for the Alliance for Prosperity Plan – Honduras – Guatemala – El Salvador | Honduras News.” Honduras News. December 20, 2015. Accessed February 18, 2016. http://www.hondurasnews.com/u-s-congress-approves-funds-for-the-alliance-for-prosperity-plan-honduras-guatemala-el-salvador/.

[18]Perla, Hector. “Central American Child Migrants”. COHA. July, 8 2014. Accessed February 1, 2016. https://coha.org/central-american-child-immigrants/

[19] Meyer, Peter and Clare Ribando Seelke.” Central America Regional Security Initiative: Background and Policy Issues for Congress”. Congressional Research Service. December 17, 2015. Accessed January 15, 2016. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R41731.pdf

[20] House of Representatives, Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2010: Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 3288, 111th Congress, 1st sess., December 8, 2009, page 343.

[21] U.S. Department of State, “Central America Regional Security Initiative, “Accessed February 12, 2016. http://www.state.gov/p/wha/rt/carsi/.

[22] Renwick, Danielle. “Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle.” Council on Foreign Relations. January 19, 2016. Accessed February 22, 2016. http://www.cfr.org/transnational-crime/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle/p37286.

[23] “Examining the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI).” Wilson Center. September 12, 2014. Accessed January 23, 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/examining-the-central-america-regional-security-initiative-carsi.

[24] Martinez, Carlos, and Roberto Valencia. “Ex-Head of El Salvador Forensics: ‘Police Committing Extrajudicial Killings'” InSight Crime. January 25, 2016. Accessed February 14, 2016. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/ex-head-of-el-salvador-forensics-police-committing-extrajudicial-killings.

[25] “Examining the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI).” Wilson Center. September 12, 2014. Accessed January 23, 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/examining-the-central-america-regional-security-initiative-carsi.

[26] Eguizábal, Cristina and Matthew C. Ingram, Karise M. Curtis, Aaron Korthuis, Eric L. Olson, Nicholas Phillips. “CRIME AND VIOLENCE IN CENTRAL AMERICA’S NORTHERN TRIANGLE How U.S. Policy Responses are Helping, Hurting, and Can be Improved”. The Wilson Center Latin American Program. Vol.34. Accessed February 15, 2016https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20PDF_CARSI%20REPORT_0.pdf

[27] Main, Alexander. “Will Biden’s Billion Dollar Plan Help Central America?” NACLA. February 27, 2015. Accessed January 02, 2016. https://nacla.org/news/2015/02/27/will-biden’s-billion-dollar-plan-help-central-america.

[28] Eguizábal, Cristina and Matthew C. Ingram, Karise M. Curtis, Aaron Korthuis, Eric L. Olson, Nicholas Phillips. “CRIME AND VIOLENCE IN CENTRAL AMERICA’S NORTHERN TRIANGLE How U.S. Policy Responses are Helping, Hurting, and Can be Improved”. The Wilson Center Latin American Program. Vol.34. Accessed February 15, 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20PDF_CARSI%20REPORT_0.pdf

[29] Martinez, Carlos, and Roberto Valencia. “Ex-Head of El Salvador Forensics: ‘Police Committing Extrajudicial Killings'” InSight Crime. January 25, 2016. Accessed February 14, 2016. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/ex-head-of-el-salvador-forensics-police-committing-extrajudicial-killings.

[30] Gagne, David. “Ex-Mayor’s Arrest Kicks Off Guatemala Anti-Corruption Campaign.” Ex-Mayor’s Arrest Kicks Off Guatemala Anti-Corruption Campaign. January 22, 2016. Accessed March 02, 2016. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-briefs/ex-mayor-arrest-kicks-off-guatemala-anti-corruption-campaign.

[31] “OAS :: Press Releases :: AVI-016/16.” OAS. February 21, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2016. http://www.oas.org/en/media_center/press_release.asp?sCodigo=AVI-016/16.