A Tradeoff: Human Rights and the Environment or National Prosperity and Growth

By: Sarah Cassidy-Seyoum, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Water is the world’s most precious resource and covers approximately 71 percent of the Earth’s surface. However, 97 percent of it is found in the world’s oceans, which means only 3 percent of water is fresh, potable, and readily available.[1] Considering that there is also an unequal distribution among countries, Brazil is fortunate to be endowed with a large amount of renewable freshwater. Since the 1970s, Brazil has used its water resources to harness electricity, and hydroelectric sites now account for around 80 percent of the country’s electricity supply.[2] Yet, the dams that it relies upon frequently attract attention for their potential to harm the country’s environment and its people, rather than for their prospective success in providing energy and economic growth. In particular, domestic and international communities have debated and criticized plans for Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam. The government approved the dam’s newest model in 2010, which will be completed by 2015, and is set to be fully functional by 2019.[3] The Brazilian government strongly believes that the dam’s potential benefits outweigh its total costs. On the other hand, many of Brazil’s people and members of the international community take an opposite stance, creating a fierce confrontation between the two sides. Ultimately, although there may be some economic and energy benefits to the dam’s construction, when considering the environmental consequences, the human rights costs, and the dam’s probable inefficiency, the Belo Monte Dam is not a valuable and just investment.

The consequences flowing from the Belo Monte Dam are not set in stone; however, in the interest of Brazil’s long-term success and security, the advantages and disadvantages must be seriously considered. This article will report a cost-benefit analysis on the dam in order to argue that it does more harm than good and determine the project’s viability. The article is split into five sections. The first section looks at the dam’s geographic location, and the second provides a brief overview of its history. Following that, the third section analyzes the costs of the dam, while the fourth examines its benefits. Finally, the last section of the article considers whether the dam should be constructed, and explores potential compromises.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE BELO MONTE

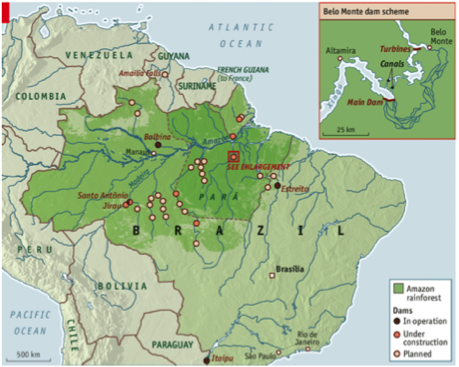

The Belo Monte Dam complex is located in the northern state of Pará, deep within the Brazilian Amazon basin.[4] It consists of two dams, two man-made canals, two reservoirs, and a large system of dikes.[5] It is being built on the Xingu River, one of the Amazon’s principal tributaries. The Xingu extends for 1,979 kilometers (km) or 1,230 miles, and flows northward from the “tropical savannah of the central Mato Groso” to the Amazon River.[6] The Belo Monte Dam will divert approximately 80 percent of the river’s water through the two canals that connect to the channel’s main reservoir.[7] The accumulated water from the reservoir channels will turn the large turbines, located in the town of Belo Monte, and convert the water’s force into electricity.

THE BELO MONTE DAM’S HISTORY

The Belo Monte project’s construction plans have been in the works since the 1970s, when a military dictatorship ruled Brazil.[8] The government’s objective was to strengthen and develop Brazil by providing “easy” access to electricity. Optimistic about spurring economic growth, the initial proposal for the complex consisted of an intricate system of six dams, one of which was the Belo Monte. The project was supposed to generate 20,000 megawatts (MW) of energy. Eletrobrás, a state-owned energy company, was intended to assume the financial burden of the project, relying on the World Bank for additional funding.[9] However, once the studies analyzing the dams’ effects were made public, its adverse consequences became obvious. On its own, the Belo Monte Dam would have caused 1,225 square km of flooding around its reservoir. The whole complex would have flooded the territories of thirteen indigenous communities and a total of 18,000 square km of the Amazon rainforest.[10]

In 1989, as soon as the domestic population and international community learned about the negative humanitarian and the adverse environmental repercussions, protests quickly erupted. As civil society pushed back, the organization Primeiro Encontro das Nações Indígenasdo Xingo (First Encounter of the Indigenous Nations of the Xingu) held demonstrations, which gained international attention.[11] Consequently, the government halted the project, though it never removed the dam from its long-term agenda. In spite of the dam construction’s standstill, the country’s hydroelectric capacity leaped by more than 400 percent between 1974 and 2004.[12]

Although the amount of electricity generated from hydroelectric plants increased, a series of events left Brazil in need of more energy sources. Therefore, modified plans for the Belo Monte Dam resurfaced in the mid 1990s, as part of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s Growth Acceleration Program (PAC). After Brazil began experiencing periodic blackouts and implemented energy rationing in the early 2000s, some argued that Belo Monte’s construction was indispensable.[13] Additionally, the 2009 mechanistic failures with the power lines from the Itaipu Dam, the world’s second largest dam, contributing 17 percent of Brazil’s electricity, caused blackouts in 18 of the 26 states.[14]

In June 2010, the government granted Norte Energia S.A., a consortium of electricity companies with shareholders that include Eletrobrás and its subsidiary, Eletronorte, permission to build the Belo Monte Dam. Construction started in 2011; however, from then on the project has been interrupted eleven times, following Brazilian court rulings.[15] In February 2011, as a result of a lawsuit filed by the Federal Public Prosecutor, a federal judge ordered the project to be stopped on grounds of environmental concern. The decision was overturned a month later, and construction resumed shortly after. Building ceased again on August 14, 2012, when members of indigenous communities spoke out, declaring that Norte Energia had not consulted them before they started construction. [16] Nonetheless, once again, this ruling was overturned and the Supreme Court authorized the Belo Monte’s construction to proceed once again.

Since then, the dam’s construction has been ongoing. When completed, the Belo Monte will be the third largest dam in the world, after the Three Gorges Dam in China and the Itaipu Dam on the Brazil-Paraguay border. It is set to have a theoretical maximum output of 11,233 MW and cost approximately $13 billion USD.[17] However, completion of the project may be further delayed, as yet another court case against the construction was recently filed on behalf of the indigenous communities.[18]

THE BELO MONTE DAM’S COSTS

There are various costs associated with Belo Monte’s construction, some of which have already have come to light. Most notably, the dam will have severe humanitarian, environmental, ecological, and economical consequences.

Violations of Human Rights and Social Impacts

The Belo Monte dam will greatly affect the city of Altamira that is located in mid-northern Pará near the dam’s main reservoir on the banks of the Xingu River (Figure 1). Due to the construction, experts expected Altamira’s population to double, and it has already increased from 70,000 to around 100,000 between 2010 and 2014.[19] As a result, the quality of life in this northern Brazilian town has considerably worsened. There is a constant hustle and bustle of construction vehicles speeding through the streets, in addition to a rising crime rate.[20] Furthermore, the price of commodities is much higher than it once was. The city has essentially reached its capacity, with construction vehicles invading its streets, and locals attempting to cope with the inflation of food prices. Living, which was once sustainable, has become harder and more expensive, and to a significant extent unsafe.

Moreover, a significant percentage of the population will be displaced. Several human rights organizations estimate that between 20,000 and 40,000 people will be forced to leave their homes because of the excessive flooding from the dam.[21] As compensation, Norte Energia promised the people of Altamira, along with other indigenous communities in the area, lofty infrastructural improvements. Such ameliorations included better sanitation systems, higher quality education, and significant strides in public health.[22] The Belo Monte project was only approved under the impression that Norte Energia would offer these benefits, which were included in clauses in the construction contract’s Basic Environmental Plan (BPA). Unfortunately, these enhancements have not yet taken place. Many indigenous communities that have been protesting the dam’s building regret not having their own copy of those promises in writing, and wonder if the terms and conditions were ever signed.[23] Ney Xipaya, one of the protesters that has been stationed outside the Norte Energia compound said, “No more leaving us only promises, and nothing on paper, because we know that with Norte Energia [that] does not work.”[24]

Additionally, the Brazilian Constitution explicitly states that indigenous populations must be consulted before the government makes any major decisions affecting them.[25] Some natives assert that the government did not consult them before the construction of the dam, leading to the termination of the project as a result of a 2012 lawsuit.[26] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights also ruled in favor of the indigenous populations in their 2011 bilateral court case, deciding that:

“ [The] state had not fulfilled the following obligations: […] to adopt substantial measures that would guarantee the personal integrity of indigenous peoples and their collective existence as such; and to take measures to prevent the spread of diseases among indigenous peoples as a result of the construction of the dam and of massive population influx.”[27]

Both the government and Norte Energia continue to endanger the indigenous peoples’ livelihood and still fail to adequately consult them over the expansive construction project. The most recent court case against building the dam takes this exclusion of indigenous interests into account.[28]

The lack of appropriate consultation with indigenous communities is only the start of the problem. Experts predict that the dam’s extensive use of the river’s water will leave a stretch of 100 km (62.14 miles), known as the Volta Grande, with little to no water.[29] This dry section of the river means that the Xingu’s fresh water fish, a vital source of nutrition for indigenous populations, are at risk of extinction. Those who navigate on the river are also adversely affected.[30] The presence of the complex system of dikes and canals is hindering navigation on the river, as the river becomes narrower and the water level drops. These two elements are key to the local population’s survival, threatening the lives of one thousand indigenous people.[31] Along with that, it also jeopardizes their culture, beliefs, and spiritual oasis. For most people in the Xingu, with the exception of the Kayapó and Suya communities, water is considered to be the “House of God” and is crucial to fostering social unity.[32] Therefore, the deterioration of this prized natural resource will shake the very foundation of their communities and be a detriment to their cultural customs and social beliefs.

Environmental Repercussions

The Amazon’s ecosystem is rich, but fragile. Tropical rainforests of its kind are home to more than half of the world’s plants and animal species, and are also the supplier of 40 percent of the earth’s oxygen.[33] The Belo Monte dam’s construction has already destroyed more than 500 square miles of the Amazon’s rivers and forests.[34] In addition, the amount of soil moved for the dam’s construction exceeds that displaced during the construction of the Panama Canal. Even the slightest of environmental changes can cause a cascade of them, undoubtedly negatively affecting the region’s ecosystem. The aforementioned loss of fish is just a fraction of the damage to the flora and fauna of the region if careless construction of the dam continues.

Brazil has only used one third of its hydroelectric potential, and the majority of its untapped sources lie within the Amazon basin. Of the 48 planned dams, 30 are located in the rainforest (Figure 2), so an increase in hydropower would result in a substantial escalation in deforestation.[35] Deforestation from the construction means that the forest will not produce as much oxygen, leading to a general rise in the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Deforestation also causes erosion—the process by which the earth’s surface is worn away by rain, winds, and other natural phenomena.[36] The hydrologic ramifications of the Belo Monte’s construction will exacerbate the effect of the rainy season’s heavy downpours, and the dry season’s droughts. The earth that is destabilized through deforestation will be more prone to erosion under these circumstances because of the large amounts of water and flooding likely to be present during upcoming rainy seasons. During the dry season, the arid, dusty earth will become more easily susceptible to natural forces, as the dam will utilize the small amount of water flowing through the river to generate electricity. In addition, the lack of water will greatly impact agriculture, as the amount of water needed for irrigation will be scarce.

ECONOMIC VIABILITY

The region’s biome and climate will hinder electricity generation. Pará is part of the tropical rainforest, meaning that it has a high average rainfall of more than 2,300 millimeters (mm) or 7.5 inches annually.[37] That being said, the rainy season only lasts for a four-month period from February to May, and there is hardly any rainfall during the rest of the year.[38] The fluctuation in rainfall throughout the year will likely keep the dam from reaching its full potential, since it will not be able to produce a steady stream of electricity. According to some estimates, the Belo Monte will only achieve 40 percent of its potential output.[39] Yet, the government fails to acknowledge this limitation, instead promoting the idea that the dam will supply electricity to 40 percent of Brazil’s households with full capacity.[40] Nevertheless, this inefficiency brings up the question of economic viability.

When Norte Energia S.A. initiated the project in 2010, the estimated cost of construction was $25.8 billion Reais, approximately $11.6 billion USD. Since then the cost has climbed to $29 billion Reais, approximately $13 billion USD. Interestingly, a 2008 estimate from Eletrobrás put the cost of the dam at $8 billion Reais.[41] However, many experts believe that there is no way that the project will stay within its budget. According to The Economist, “Brazil’s institutions are ill-suited” to estimating costs accurately. In addition, precedent has shown that major dam projects’ costs rarely remain within the confines of their proposed budgets.

A survey of 245 dams ranging over 65 countries, found that 96 percent of dam projects had cost overruns and 44 percent of them had schedule delays.[42] The survey also estimated that “half of the 245 large dams […] are nonviable, meaning they won’t be able to redeem the cost of building them.”[43] The aforementioned Itaipu Dam, between Brazil and Paraguay, surpassed its budget by 240 percent, causing years of economic hardship for Brazil.[44] The Belo Monte Dam is likely to exceed its budget because of its inability to fully utilize its electricity generation potential. Ultimately, the author of the study estimates that the cost of the dam could reach $27 billion USD.[45]

Furthermore, Norte Energia is a state-owned company, not a private institution; therefore adding insult to injury, the burden of increased costs will fall on the taxpayers. Although the government claims that the costs are solely Norte Energia’s problem, taxpayers are indirectly funding the project.[46] The government believes that Belo Monte is economically viable, but in reality, the project may not bring the prosperity the government so dearly desires.

THE BENEFITS OF THE BELO MONTE DAM

According to the government, the Belo Monte Dam offers more advantages than disadvantages. What some activists, scientists, and economists see as detrimental, the government and many of their officials and experts see as beneficial. They believe that the dam is the answer to Brazil’s energy shortages, and a key element that will spur national economic growth. Former energy minister and current president, Dilma Rousseff, is adamant that the project will benefit the Amazonian communities, referring to it as a “social investment.”[47] Her viewpoint is founded on Norte Energia’s promises of improvements. Maintaining a positive stance on the project, Norte Energia and the Brazilian government have effectively negated criticism from the international community and the Brazilian population. The government “guarantees that no negative impact on these populations will exist.”[48]

The Belo Monte Dam project is part of two Brazilian initiatives: the reduction of carbon emissions while maintaining energy security, and the Accelerated Growth Program (PAC). Firstly, in terms of reducing carbon emissions and maintaining energy security, Brazil intends to reduce green house gas emissions by 38 percent by 2020.[49] Belo Monte and hydroelectricity in general are critical components in solving Brazil’s growing energy demands. In order to reduce emissions and match the country’s growing energy demands, the country needs to find renewable energy sources. Fortunately, Brazil is endowed with vast energy reservoirs, and possesses the third-largest potential for hydroelectricity behind China and Russia.[50] According to a study undertaken by the energy ministry, hydropower is appealing because it is readily available, cheap, and renewable. Furthermore, Brazil also has among the largest potential for solar and wind energy.[51] In the end, Brazil can also still rely on its non-renewable offshore oil deposits and its prosperous biofuels industry.

Secondly, in terms of economic growth and development, proponents of the dam argue that it will foster prosperity by harnessing much needed electricity, creating employment, and strengthening the Brazilian economy. With regards to electricity generation, according to the Energy Research Company, the research branch of the Mines and Energy Ministry, Brazil needs to add 6,350 MW of energy every year until 2022.[52] If the Belo Monte Dam were to generate its maximum output of 11,233 MW, then it would provide one-fifth of the needed energy. However, as previously discussed, the dam will likely not be able to reach this maximum output. Hence, the Belo Monte would contribute to Brazil’s energy demands, but not to an overwhelming extent.

The largest gain from the construction of the dam is the number of employment opportunities it is creating. There are currently 25,000 people working to build the third largest dam in the world.[53] Fifty four percent of those employed are from Pará, and within that, 32 percent are from the city of Altamira. Therefore, Norte Energía is offering employment to the local people. Further illustrating the impact of these job opportunities are the workers opinions on workplace conditions. Sixty four percent of them believe the conditions are good and excellent, 30 percent believe they are average, and only 5 percent believe conditions are poor. Additionally, 88 percent of the workers approve of the construction of the dam.[54] These statistics highlight the importance of the role the dam plays in generating employment opportunities.

Moreover, the dam’s investment and construction will inherently create an economic chain effect that will boost both the local and national economies. The building of the dam offers people employment, allowing them to invest in their future, while paying for immediate necessities. When people have disposable income, they start buying and consuming more. Hence, as the demand grows, the consumption will spur the local economy and contribute to overall growth in the Brazilian economy.

DO THE BENEFITS OUTWEIGH THE COSTS? WHAT ARE POSSIBLE COMPROMISES?

There is no doubt that the Belo Monte’s costs outweigh its benefits. However, the magnitude of the costs and the extent of the gains will determine whether the construction of the dam is viable. When looking at the advantages and disadvantages of the dam, economists and scientists around the world have drawn conclusions regarding the dam’s economic viability and consequences, contradicting reports by the Brazilian government and Norte Energia.[55] In an analysis of these contradictions lies the answer to the true worth of the dam.

These discrepancies are apparent in terms of economic viability and growth, and the consequences on the local economy, society, and surrounding communities, as well as the energy’s ecology. On a local economy scale, Norte Energia believes it is helping the job market. With the increased need of catering to the construction workers, and the employment of certain locals by the company, job prospects have been heightened. Theoretically, the local economy should benefit from Norte Energia’s presence and the dam’s construction. However, the jobs will only be present while the dam is still under construction. Therefore, although there are short-term gains, long-term employment will be non-existent. Despite this, as of mid-2013, the local population is calling for more jobs and income, and technically, the dam project does indeed provide opportunities.[56]

The Brazilian government is confident that the Belo Monte, and other dam projects, will significantly contribute to the nation’s overall development. That being said, the highlighted flaw in the project is the inefficacy of the dam because of the extreme seasonal variation in precipitation. This will most probably be the case with any other dam that is being planned in the Amazon rainforest. The Belo Monte Dam itself will on average only produce 4,500 MW out of its maximum 11,233 MW per year.[57] It appears that the project will not be as effective as initially expected; therefore, it will contribute less to the country’s economic growth and development and fail to provide the amount of energy needed. With the dam’s large scale and its destruction of 500 square miles of the Amazon rainforest and rivers, the potential yearly output is much too low. Norte Energia is undertaking an unnecessarily large operation, when a smaller dam could very well produce similar amounts of electricity.

Furthermore, Norte Energia claims that the dam will not negatively affect the surrounding towns and villages. They also insist that the indigenous communities’ forced displacement will not occur because their locality will not be flooded.[58] In their opinion, the local people will benefit from the various improvements the company is offering. However, there are two weaknesses in their argument. First, it is clear that floods will take place, thereby causing people to relocate. Second, three years on, the proposed improvements that they refer to have not yet materialized.

The final area of disagreement is the ‘green’ nature of the dam. As previously mentioned, the hydroelectric power plants are part of the initiative to reduce carbon emissions and lead Brazil to a ‘greener’ future. Despite the Belo Monte’s contribution to renewable energy, the dam seems to create more environmental problems than it fixes. It might constitute a grander plan to decrease emissions, but it also will injure the environment by felling trees and diverting rivers. Further, some scientists believe that the dam will actually exacerbate green house gas production. This could occur because the vegetation’s destruction and reservoir’s flooding will release methane.[59] Ultimately, the hydroelectric plant is not as environmentally friendly as it should be. In light of this situation, Brazil must utilize its other renewable energy (wind and solar) potential, and reduce the number of already planned hydroelectric power plants. Brazil’s energy security can profit from wind and solar energy sources, even when combined with fewer dams overall.

When considering the dam’s inefficiency, consequences on the surrounding communities, and environmental repercussions, the costs outweigh its benefits. Despite excessive costs and sparse benefits, construction is unlikely to be halted. That being said, Norte Energia’s promises to the local people must be publicly honored and officially implemented. Before that takes place, construction must be temporarily halted to pave way for a comprehensive governmental conference in which all affected parties are represented. This discourse is especially important as the dam’s construction progresses and tensions escalate.

The indigenous communities feel as if Norte Energia is ignoring their voices and are contemplating abandoning peaceful protests as a means of airing their grievances. The indigenous people sent a letter to the National Indian Foundation declaring, “For now we are in a peaceful demonstration,” implying the possibility of violence.[60] It seems fair and just that the indigenous communities and others in the area surrounding the dam should have a say in its construction.[61] Therefore, in addition to the improvements that were promised, a thorough consultation with the indigenous communities and a formal agreement between both parties must be carried out before the government once again recommences the dam’s construction. Though the indigenous communities would want the project to be terminated, they will at least get some form of compensation in this scenario. Nonetheless, their complaints have reached an international audience. In March at the 25th United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, the national coordinator of Brazil’s Association of Indigenous Peoples Sônia Guajajara made clear the extent to which human rights have been violated in stating that “The alliance of economic interests and political power represent a major crisis for the implementation of indigenous rights in today’s Brazil.”[62]

The indigenous people’s interests are closely intertwined with nature and their environment. The environmental and ecological losses as a result of the dam’s construction cannot be assigned a monetary value; they are priceless. This characterizes a grass-roots movement sweeping Latin America, the buen vivir movement, which aims to “decide to build a new form of public coexistence, in diversity and in harmony with nature, to achieve the good way of living.”[63] This is a promising people’s movement, unfortunately its impact will most likely be felt too late to save the Brazilian Amazon and its population’s livelihood.

With the Brazilian Supreme Court’s verdicts’ reversals, it is clear that the dam has the government’s full backing. Regardless of the consequences, the dam’s construction will most likely take place, though the upcoming Brazilian elections in October may offer a glimmer of hope. The elections feature a candidate, Marina Silva, who is an environmentalist and activist. She will probably lose the election, but even if she were to win the probability that she would be able to stop the construction of the dam is low, especially because it is 47 percent complete.[64] Unfortunately, at least for now, the quest for economic growth and development appear to have prevailed over human rights and environmental repercussions, even though they should not. The indigenous peoples’ rights have rarely been taken seriously, and this trend only continues. The entire global ecosystem will forever be altered, as the world’s forests continue to quickly disappear. There are other solutions to the increased energy demand and the pressing need for greenhouse gas reduction. It is better to explore those, before destroying the most diverse ecosystem on the planet. If the dam were more efficient and truly generated its maximum output, then maybe its construction could be considered a gain. However, as it currently stands, the earth and its people are being grievously harmed, and the project does not justify the very heavy price that is expected and does not seem all that worth it.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

References:

[1] National Ocean Service. “Ocean Facts.” Where Is All the Earth’s Water? National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 11, 2013. April 3, 2014. http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/wherewater.html.

[2] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.” The Economist. May 4, 2013. July 7, 2014. http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21577073-having-spent-heavily-make-worlds-third-biggest-hydroelectric-project-greener-brazil.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kylie Schultz, “The True Cost of Belo Monte, Life on the Amazon and Brazil’s Energy Crisis.” The International. January 31, 2013. July 15, 2014. http://www.theinternational.org/articles/324-the-true-cost-of-belo-monte-life-on-the.

[6] “Xingu River.” International Rivers. July 7, 2014. http://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/xingu-river.

[7] Elissa Curtis. “The dark side of Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam.” MSNBC. June 18, 2014. July 5, 2014. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/belo-monte-dam-brazil-environmental-crisis.

[8] Vinodh Jaichand, Alexandre Andrade Sampaio.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Eve Z. Bratman, “Contradictions of Green Development: Human Rights and Environmental Norms in Light of Belo Monte Dam Activism.” Journal of Latin American Studies 46, no. 2 (2014): 261 – 289.

Vinodh Jaichand, Alexandre Andrade Sampaio.

[11] Vinodh Jaichand, Alexandre Andrade Sampaio.

[12] Eve Z. Bratman.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[15] C.J. Schexnayder. “Brazilian Court Halts Belo Monte Dam Construction.” Energy News-Record 269: 1.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[18] AIDA, “Brazil Organizations Challenge Legality of the Belo Monte Dam in Court.”Upside Down World. July 5, 2014. July 7, 2013. http://upsidedownworld.org/main/news-briefs-archives-68/4919-brazil-organizations-challenge-legality-of-belo-monte-dam-in-court.

[19] “Altamira.” City Population Germany. July 12, 2014.http://www.citypopulation.de/php/brazil-para.php?cityid=1500602.

Francho Barón. “Las máquinas desembarcan en la selva amazónica.” Arkinka 16, no. 197 (2012): 18-20.

[20] Francho Barón.

Elissa Curtis.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, Francho Barón.

[23] “Brazil: Amazon Indians shot at Belo Monte dam site.” The Ecologist. May 30, 2014. June 27, 2014. http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_round_up/2416353/brazil_amazon_indians_shot_at_belo_monte_dam_site.html.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Council on Hemispheric Affairs, “Belo Monte Dam: Not Just A Threat to the Environment.” The Council on Hemispheric Affairs. July 23, 2012. July 8, 2014. https://coha.org/belo-monte-dam-not-just-a-threat-to-the-enviroment/.

[26] C.J. Schexnayder.

[27] Vinodh Jaichand, Alexandre Andrade Sampaio.

[28] AIDA.

[29] Vinodh Jaichand, Alexandre Andrade Sampaio. “Dam and Be Damned: The Adverse Impacts of Belo Monte on Indigenous Peoples in Brazil.” Human Rights Quarterly 35, no. 2 (2013): 408-447.

[30] Kenneth Rapoza. “Was Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam a Bad Idea?” Forbes. July 3, 2014. July 7, 2014. http://www.forbes.com/fdc/welcome_mjx.shtml.

[31] “Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam: Sacrificing the Amazon and its Peoples for Dirty Energy.” Amazon Watch. 2014. July 7, 2014. http://amazonwatch.org/work/belo-monte-dam.

[32] The Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

[33] Michael G. “Tropical Rainforest.” Blue Planet Biomes. 2001. July 12, 2014. http://www.blueplanetbiomes.org/rainforest.htm.

[34] Kylie Schultz.

[35] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[36] “Erosion.” Dictionary.com. July 12, 2014.http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/erosion.

[37] “Amazon Facts.” Project Amazonas. July 12, 2013. http://www.projectamazonas.org/amazon-facts.

[38] Marcelo Leite. Dimmi Amora, Morris Kachani, Lalo de Almeida, Rodrigo Machado.“All about the Belo Monte Dam.” Folha de São Paulo. Translated from Portuguese by Michael Kepp.http://arte.folha.uol.com.br/especiais/2013/12/16/belo-monte/en/.

[39] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[40] Blake Schmidt, “Megadams Are Dismal Investments.” Bloomberg Business. March 13, 2014. July 15, 2014. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-03-13/megadams-are-dismal-investments.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[47] Blake Schmidt.

[48] Francho Barón.

[49] Kylie Schultz.

[50] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[51] Ibid.

[52] Marcelo Leite. Dimmi Amora, Morris Kachani, Lalo de Almeida, Rodrigo Machado.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Blake Schmidt.

[56] “Dams in the Amazon: The rights and wrongs of the Belo Monte.”

[57] Ibid.

[58] Francho Barón.

[59] Kylie Schultz.

[60] “Brazil: Amazon Indians shot at Belo Monte dam site.”

[61] C.J. Schexnayder.

[62] “Indigenous Leader Condemns Brazil’s Rights Abuses at United Nations.” Amazon Watch. March 11, 2014. August 19, 2014. http://amazonwatch.org/news/2014/0311-indigenous-leader-condemns-brazils-rights-abuses-at-united-nations.

[63] Oliver Balch. “Buen vivir: the social philosophy inspiring movements in South America.” The Guardian. February 4, 2013. August 19, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/buen-vivir-philosophy-south-america-eduardo-gudynas.

[64] Marcelo Leite. Dimmi Amora, Morris Kachani, Lalo de Almeida, Rodrigo Machado.