A Legacy of Violence: Impunity for Murdered Journalists Continues in Paraguay

By Louise Højen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

On October 16, investigative journalist Pablo Medina and his young assistant, Antonia Almeda, were murdered in an ambush all but certainly orchestrated by Brazilian drug cartels and the mayor of the Ypejhú district, Vilmar ‘Neneco’ Acosta Marqués, in Paraguay’s northeastern Canindeyú Department. These killings reveal a disturbing influence of drug cartels, political corruption, and a legacy of violence in Paraguay that needs to be addressed.

Impunity Prevails Again

Medina, regional correspondent for the Paraguayan daily ABC Color since 1998, was a victim of continued death threats throughout his career in Paraguay. For Paraguayan society, this was not an isolated incident but the sad reality for many journalists who dare to buck the trend in the country.[1] He is the third fatality this year, displaying what is tantamount to a grave lack of protection of investigative journalists in Paraguay. The event also sheds light on repression of press freedom and on a corrupt legal system endemic to the nation that has sadly failed to find and prosecute the killers of Medina and Almeda. Today, the offenders still go unpunished despite the testimony from the remarkably brave Juana Ruth, Almeda’s sister. She managed to survive the violent killings in October by hiding in the backseat of Medina’s car; Juana recognized one of the assassins as being Wilson Acosta Marqués, brother of the fugitive Mayor Neneco from Ypejhú.[2] Moreover, the roots of corruption seem to go even deeper with the implication of high-ranking officials, such as Congresswoman Maria Cristina Villalba, unofficially known as “the drug queen,” and Governor Alfonso Noria Duarte of Canindeyú. Both are suspected of protecting the network of drug cartels in Canindeyú, including Neneco. Yet, more thorough investigation and prosecution remain to be seen.[3] The recent murders and the government’s subsequent inaction have sparked national indignation, which also is pertinent to past killings that continue to be unsolved.

A Legacy of Violence

As most of Latin America, Paraguay has a long and turbulent history with bloody conflicts and dictatorships.[4] The last dictatorship ended in 1989 after a military coup d’état against then President Alfredo Stroessner, who had ruled Paraguay since 1954. Stroessner held the country on a tight leash, dismissing human rights and, according to The Washington Post, created a paradise for “smugglers in arms, drugs and everyday goods such as whiskey and car parts.”[5] This violent period has left an undeniable mark on the country and helped create its current milieu of drug politics. According to a The Washington Post interview with Eduardo A. Gamarra, former Director of the Latin American and Caribbean Center at Florida International University, the Stroessner dictatorship left Paraguay with a heavy legacy that continues to influence today’s society because of an “absence of political institutions” and the challenge of “[c]onstructing stable democratic institutions.”[6]

This dark inheritance has become increasingly evident with the growing insecurity for journalists in Paraguay. On May 16 this year, journalist Fausto Gabriel Alcaraz was murdered. In Paraguay’s eastern border city of Pedro Juan Caballero, located in the Amambay department, unknown men on motorcycles shot and killed the radio host who worked for Radio Amambay.[7] Sadly, he was not the first to be brutally gunned down near the Brazilian border. A radio host director, Santiago Lequizamón, was murdered in Pedro Juan Caballero in 1991, as was the director of the local radio Sin Fronteras (Without Borders), Marcelino Vásquez, on February 6, 2013.[8]

The second journalist killed in Paraguay this year was Edgar Pantaleón Fernández Fleitas. On June 19, an unknown assailant shot him dead in his home in Concepción. He was a general practice attorney but also had his own radio show, Ciudad de la Furia (City of Fury), where he boldly criticized local judges, lawyers, and officials in the Attorney General’s office for corrupt practices.[9] The most recent executions of Medina and Almeda show how drug-related violence, almost certainly masterminded by corrupt politicians, is escalating and creating an increasingly unsafe environment for the freedom of press in Paraguay. It is also evident that the young democratic system in Paraguay is struggling to address civil threats and curtail ongoing historic violence.

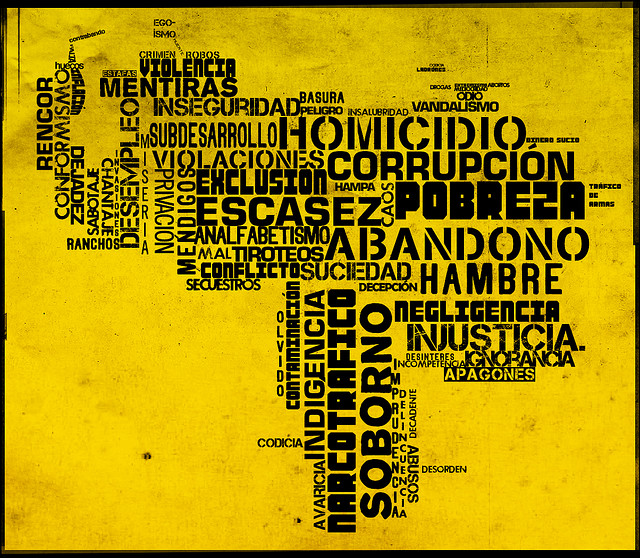

Image by: Juan Carlos Aristimuño. Taken from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jcaristimuno/4085357282/in/photostream/

Paraguay: A Pawn in the Dark World of Drugs

Paraguay is a small, landlocked country in South America and the second largest producer of marijuana in the entire Latin American region, only after Mexico.[10] In fact, Paraguay has been labeled a “top pot producer” for several years now, according to reports from CNN, El Mundo, and InSight Crime, among others.[11] This disconcerting feature is often overlooked by international institutions such as the United Nations (UN), in comparison to high-profile producers like Afghanistan or Morocco. In Latin America, reports are mostly directed at the production of cocaine, where Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia are the most prominent producers, and even if marijuana makes the agenda, it is most often related to the flow of drugs from Mexico to the United States.[12] Amidst these drug-producing countries, Paraguay is often neglected as an important factor, despite its massive marijuana production fields that cover from some 5,000-8,000 hectares of land.[13]

A likely explanation is that most of Paraguay’s production never reaches beyond the regional borders, not even to the United States. Rather, Paraguay’s exports go straight to South American countries like Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.[14] Paraguay is struggling with its corrupt politicians and organized crime, which is tightly controlled by cartels that are directing the drug production from across the Brazilian border. Therefore, Paraguay’s departments that border Brazil are the most severely affected by drug-related violence, especially Alto Paraná, Amambay, Canindeyú, Concepción, but also San Pedro.[15] According to the “Paraguay 2014 Crime and Safety Report” by Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), Paraguay functions as a transit for cocaine too, but marijuana is most likely the prevalent issue. The affected departments, if not all of Paraguay, are caught in the crossfire between the ruling Brazilian gangs that control Paraguay: “[I]t is believed that members of the Brazilian organized crime gang First Command of the Capital (PCC) are operating in Pedro Juan Caballero (Amambay), Salto de Guairá (Canindeyú), and Cuidad del Este (Alto Parana).”[16]

A big issue with Paraguay’s far-flung marijuana cultivation is that many local cultivators support it because the industry pays well. Disconcertingly, fluctuations in the marijuana production have a direct impact on the country’s national economy as well as contributing to social and economic stability in the cultivated departments. This makes it even harder to fight the drug industry and the powerful cartels.[17] This struggle has been emphasized by Luis Rojas, the Minister for the National Anti-Drug Secretariat (SENAD, Secretaría Nacional Antidrogas), while admitting that there simply are too few agents to combat the cartels and drug production effectively.[18]

Similarities with Mexico

Given the current situation, it is obvious that drug trade is a severe problem in Paraguay and that the criminal environment and lack of a stable democratic system throughout the country most likely have been sustained since the Stroessner dictatorship. Moreover, Paraguay’s drug problems have reached deep into society by influencing not only civil society, but also the nation’s political and economic realm. What is coming to light in Paraguay is somewhat similar to the violent problems that Mexico has been experiencing for many years.[19] Both countries are giant cannabis herb producers and their societies are haunted by powerful drug cartels. Moreover, both countries traditionally have faced problems with repression of the press and organized violence against journalists, though Mexico’s case is even graver than that of Paraguay.[20] However, as Paraguay faces similar challenges concerning drug-related violence, corrupt politicians, and impunity, lessons can be learned just by looking at Mexico’s experiences: the grave drug-related issues currently taking place in the country as well as the lack of action from the government that has sparked a national uproar.[21]

An Ongoing Struggle for Justice

The recent killings of Medina and Almeda remain unpunished despite national and international condemnation. Journalists and citizens have shown their solidarity since the murders through demonstrations that demand justice and accountability from the government. In the capital, Asunción, demonstrations have been targeted specifically at the narcogobierno (drug government).[22] The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the regional Federation of Journalists in Latin America and the Caribbean (FEPALC), Reporters Without Borders (RSF, Reporters Sans Frontières), and the United Nations have also denounced the violence and demanded that the Paraguayan government must take action.[23] Local politicians, such as Neneco, have carried out the clandestine actions and the Government is held responsible for the high level of corruption, especially since multiple high-ranking officials appear to be involved in the drug industry. To avoid initial pressure from the population, President Horacio Manuel Cartes Jara denounced the killings of Medina and Almeda right after they occurred.[24] However, the process to achieve results from the subsequent investigation has proven to be painstakingly slow.

In the search for justice, SENAD Minister Rojas met up with Senator Arnaldo Giuzzio on November 19 to investigate other Paraguayan officials connected to the drug industry. Congressmen Freddy D’Ecclessis, Marcial Lezcano, and Bernardo Villalba, all connected to the governing Colorado Party (PC, Partido Colorado), appear to belong to a larger network of corrupt politicians and lawyers.[25] Despite the evidence presented by SENAD, the Chamber of Deputies has decided to let them keep their positions in the Senate and will neither go into deeper investigation nor advance their prosecutions before the Attorney General’s Office has filed a formal request.[26]

The resignation of Minister of the Supreme Court of Justice, Víctor Núñez, due to grave incidents of malpractice, including a case involving the now fugitive Mayor Neneco has been a positive development.[27] Furthermore, on December 8, Neneco’s chauffeur, Arnaldo Javier Cabrero López, was detained. He was also wanted by Paraguay’s police as an accomplice to the murder of Pablo Medina and Antonia Almeda. Despite the satisfaction of capturing Cabrero, the search for Neneco and the other suspects, Wilson Acosta and Flavio Acosta, continues.[28]

On December 8, the Catholic Church joined the opposition to the drug industry, showing that not only the local population and journalists are protesting. The Bishop from the city of Caacupé, Claudio Giménez, denounced, during mass, Paraguay’s high corruption levels, and how the persons from the drug industry currently are dominating the spheres of Paraguayan politics and justice.[29]

Something is Rotten in the State of Paraguay

Numerous challenges are ahead for Paraguay with the international lack of attention to the country’s drug-related issues. The struggle to achieve justice for murdered journalists in Paraguay continues and there appears to be a growing consensus between civil society and the Catholic Church, who agree that the malpractice of corrupt politicians influenced by drug cartels must be stopped.

The development since the murders of Medina and Almeda seem to suggest that Paraguay is struggling not only with strong drug cartels and corrupt politicians, but essentially a dark historic legacy, made up by dictatorships and violence. Freedom of the press and the protection of human rights need to be part of the national agenda in order to promote a democratic system. However, Paraguay needs help to combat the drug industry, whether it be from regional allies, the United States, the European Union, the U.N., or some other international body. If not, Paraguay will remain in peril of becoming a country driven by drug politics like Mexico, whose situation is even graver. It is imperative for Paraguay to come to terms with its dark legacy of violence, end the unabated rule of drug cartels and corrupt politicians, and begin to protect and promote freedom of the press.

By Louise Højen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

The latest article on Paraguay published by Council on hemispheric Affairs can be reached here: https://coha.org/pablo-medina-paraguays-third-victim-of-drug-politics/

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

[1] Højen, Louise. “Pablo Medina: Paraguay’s Third Victim of Drug Politics,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Oct 24. Accessed Nov. 20, 2014: https://coha.org/pablo-medina-paraguays-third-victim-of-drug-politics/

[2] El Nuevo Herald. “Expulsan Alcalde Acusado De Asesinato en Paraguay,” Nov. 7, 2014. Accessed Nov. 25, 2014: http://www.elnuevoherald.com/noticias/mundo/america-latina/article3651242.html

[3] ABC Color. ”Denuncian Persecución de la Diputada y el Gobernador,” Nov. 22, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/edicion-impresa/politica/denuncian-persecucion-de-la-diputada-y-el-gobernador-1308704.html

[4] Roberts, Dylan W. ”Create, Establish, Maintain: Comparing Zones of Peace in the Nordic Area and the Southern Cone,” Florida International University, FIU Digital Commons, May 14, 2014, p. 106. Accessed Dec. 3, 2014: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2649&context=etd

[5] Bernstein, Adam. “Alfredo Stroessner; Paraguayan Dictator,” The Washington Post, Aug. 17, 2006. Accessed Dec. 1, 2014: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/08/16/AR2006081601729.html

[6] Bernstein, Adam. “Alfredo Stroessner; Paraguayan Dictator,” The Washington Post, Aug. 17, 2006. Accessed Dec. 1, 2014: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/08/16/AR2006081601729.html

[7] Reporters Without Borders. ”Second Paraguayan Journalist Slain near Brazil’s Border in Less Than Two Years,” May 19, 2014. Accessed Nov. 25, 2014: http://en.rsf.org/paraguay-second-journalist-slain-in-border-19-05-2014,46305.html

[8] Reporters Without Borders. ”Second Paraguayan Journalist Slain near Brazil’s Border in Less Than Two Years,” May 19, 2014. Accessed Nov. 25, 2014: http://en.rsf.org/paraguay-second-journalist-slain-in-border-19-05-2014,46305.html

[9] Committee to Protect Journalists. “Edgar Pantaleón Fernández Fleitas,” Jun. 19, 2014. Accessed Nov. 25, 2014: http://cpj.org/killed/2014/edgar-pantaleon-fernandez-fleitas.php

[10] Cappelli, Dino. “Paraguay, El Mayor Productor De Marihuana De América Del Sur,” El Mundo, Oct. 7, 2014. Accessed Nov. 25, 2014: http://www.elmundo.es/america/2014/10/07/5433279a268e3e234a8b4570.html

[11] CNN. “Mexico, Paraguay Top Pot Producers, U.N. Report Says,” Nov. 25, 2008. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://edition.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/americas/11/25/paraguay.mexico.marijuana/ ; El Mundo. “Paraguay, El Mayor Productor De Marihuana De América Del Sur,” Oct. 7, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.elmundo.es/america/2014/10/07/5433279a268e3e234a8b4570.html ; McDermott, Jeremy. “Paraguay’s Top Anti-Drug Agent Talks Marijuana Trade,” Sep. 17, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/paraguay-s-top-anti-drug-agent-talks-marijuana-trade

[12] United Nations. ”World Drug Report 2014,” United Nations Office on Drug and Crime, June 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2014/World_Drug_Report_2014_web.pdf

[13] El Mundo. “Paraguay, El Mayor Productor De Marihuana De América Del Sur,” Oct. 7, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.elmundo.es/america/2014/10/07/5433279a268e3e234a8b4570.html ; McDermott, Jeremy. “Paraguay’s Top Anti-Drug Agent Talks Marijuana Trade,” Sep. 17, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/paraguay-s-top-anti-drug-agent-talks-marijuana-trade

[14] El Mundo. “Paraguay, El Mayor Productor De Marihuana De América Del Sur,” Oct. 7, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.elmundo.es/america/2014/10/07/5433279a268e3e234a8b4570.html

[15] The Research & Information Support Center (RISC). “Overall Crime and Safety Situation,” in Paraguay 2014 Crime and Safety Report by Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), Aug. 27, 2014.

[16] The Research & Information Support Center (RISC). “Overall Crime and Safety Situation,” in Paraguay 2014 Crime and Safety Report by Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), Aug. 27, 2014.

[17] McDermott, Jeremy. “Paraguay’s Top Anti-Drug Agent Talks Marijuana Trade,” Sep. 17, 2014. Accessed Nov. 26, 2014: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/paraguay-s-top-anti-drug-agent-talks-marijuana-trade

[18] ABC Color. ”Senad no Puede con el Narcotráfico,” Oct. 17, 2014. Accessed Oct. 21, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/no-pueden-con-el-narcotrafico-1296838.html

[19] For a deeper analysis of violence in Mexico, see Pineo, Ronn. “Violence in Mexico and Latin America,“ Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Feb. 21, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: https://coha.org/violence-in-mexico-and-latin-america/

[20] Huang, Fei. “The Paradox of Free Expression in Mexico,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Dec. 3, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: https://coha.org/the-paradox-of-free-expression-in-mexico/

[21] Huang, Fei. “The Paradox of Free Expression in Mexico,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Dec. 3, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: https://coha.org/the-paradox-of-free-expression-in-mexico/

[22] ABC Color. ”Multitudinaria Caravana por Pablo en Curaguaty,” Oct. 19, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/edicion-impresa/politica/multitudinaria-caravana-por-pablo-en-curuguaty-1297409.html ; ABC Color. ” Periodistas se manifiestan frente al Palacio de López,” Oct. 30, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/edicion-impresa/politica/periodistas-se-manifiestan-frente-al-palacio-de-lopez-1301000.html

[23] International Federation of Journalists. ” Murderers of Paraguayan Journalist, Pablo Medina Velasquez, Must Be Punished,” Oct. 21, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: http://www.ifj.org/nc/news-single-view/backpid/1/article/murderers-of-paraguayan-journalist-pablo-medina-velasquez-must-be-punished/ ; Reporters Without Borders “Reporters Killed in Ambush after Police Protection Withdrawn,” Oct. 20, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: http://en.rsf.org/paraguay-reporter-killed-in-ambush-after-20-10-2014,47125.html ; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural organization (UNESCO). “Director-General Denounces Killing of Paraguayan Journalist Pablo Medina Velázquez and his Assistant Antonia Maribel Almada Chamorro,” UNESCOPRESS, Oct. 24, 2014. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/freedom-of-expression/press-freedom/unesco-condemns-killing-of-journalists/

[24] TeleSUR. “Paraguayan Journalist Murdered,” Oct. 17, 2014. Accessed Oct. 21, 2014: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Paraguayan-Journalist-Murdered-20141017-0035.html

[25] ABC Color. ”Nombres de la Narcopolítica,” Nov. 20, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/exponen-datos-de-narcopolitica-1308086.html

[26] TeleSUR. “Paraguay: Legislators Accused of Narcopolitics Won’t Be Removed,” Dec. 1, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Paraguay-Legislators-Accused-of-Narcopolitics-Wont-Be-Removed-20141201-0057.html

[27] ABC Color. ”Renuncia Víctor Núñez,” Dec. 2, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/renuncia-victor-nunez-1304754.html

[28] ABC Color. ”Detienen a Chofer de Neneco,” Dec. 8, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/cae-chofer-de-neneco-1313928.html

[29] ABC Color. ”Obispo de Caacupé, Contra los Marcos y Masones,” Dec. 8, 2014. Accessed Dec. 8, 2014: http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/contra-los-narcos-y-masones-1313919.html