Controversial Alternative for a Trapped Labor Force: Mexico’s Formal Employment and Illicit Drug Production

By Briseida Valencia Soto, Research Associate at Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Mexico’s disenfranchised often see the illicit drug economy as an escape route from poverty. Mexican drug cartels post annual gains between approximately $18 and $39 billion USD.[1] For Mexico’s poorest, the promise of quick and exorbitant profits is often too enticing to pass up. To put the allure of the drug trade into context, take for example the juxtaposition between Mexico’s drug and crude oil economies: In 2014, crude petroleum, Mexico’s primary export, was worth $37 billion, an estimated $3 billion less than the illicit drug economy’s worth at its highest value.[2] The oil industry, which until recently was controlled by PEMEX, the national oil company, employed 151,000 workers in 2013.[3] In the early 1990s, the Sinaloa Federation, the largest and most powerful cartel conglomerate at the time, employed an estimated 100,000 individuals.[4] While PEMEX’s 2014 workforce is somewhat larger, it is important to consider that the Sinaloa Federation was only one of dozens of Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in the 1990s. As such, it is logical to conclude that the illicit drug economy in the ‘90s offered employment to a massive workforce. Since the ‘90s, Mexico’s drug industry has only grown in scale. To make matters worse, the narcotics industry, while far riskier than the formal economy, offers Mexico’s poor viable work opportunities. Recently, the spike in heroin use in the United States (a 90 percent increase between 2002 and 2013)[5] has contributed to a boom in production and illicit employment opportunities. Moreover, because of the state’s failure to suppress the drug economy, the drug business has taken on a veneer of folkloric invincibility that contributes to its attractiveness.

Corruption and Weak Law Enforcement

The illicit drug economy is a symptom of historical corruption and deep-seated inequality in Mexico that has been exacerbated by superficial anti-drug policies. Despite directed efforts at stifling the drug trade, recent attempts by the government have largely failed. Felipe Calderón’s Sexenio, which was blatant in its anti-drug stance, made negligible advances against the drug industry. Calderon’s “hardline” approach to combating drug cartels was marred by significant collateral damage. President Calderón left office with a poor human rights record over his head; kidnappings, extortions, and extrajudicial killings became the norm during his term. To get a sense for the inefficacy of Calderón’s drug policy one only has to examine the cat-and-mouse game that his administration played with Joaquin Guzmán Loera–better known as El Chapo. Guzmán Loera, considered the most infamous drug trafficker of recent times, evaded the law for much of his career. Though now facing possible extradition to the United States, Guzmán Loera’s criminal trajectory made evident the nearsightedness and ineptitude of President Calderón’s anti-drug strategy.

Although Calderón’s term ended in 2012, his national drug policy lives on. To end the drug war, Mexico must focus on alleviating severe poverty and inequality by investing in various social and educational programs. To achieve tangible results, it must do this while simultaneously tackling government corruption. Much of Mexico’s corruption stems from the inherent weakness of its institutions, particularly its law enforcement bodies, which have often served private interests.[6] This has bred a culture of incompetence that has made the task of combating illicit drug networks nearly impossible. Drug cartels operate within much of Mexico with little resistance from law enforcement. In an effort to improve the situation, President Enrique Peña Nieto, Felipe Calderón’s successor, has dealt with the situation in much the same way as his predecessor: both increasing military brutality and violating human rights. Oftentimes, these hardline tactics affect the wrong populations: poor, subsistence-level farmers, and young persons.

The number of homicides in Mexico is ever-rising—a direct result of recent presidents’ attempts at solving the drug problem.[7] The country’s armed forces are efficient killers; while combat between cartel groups usually results in four persons injured for every one kill, the military injures one person for every eight kills.[8] April’s average daily murder rate of 56.1 percent was the worst recorded since the government began officially counting victims in January 2014.[9]

The Economy and Drugs

Drug cartels first began to emerge as a consequence of Mexico’s 1982 debt crisis and staggering unemployment rates. Many viewed the narcotics industry as a viable alternante means of income. Today, however, Mexico faces no economic crisis. On the contrary, Mexico is the 12th largest export-driven economy in the world. In 2014 Mexico exported $400 billion USD and imported $379 billion USD in goods (a trade surplus of $21 billion USD).[10] In addition, the unemployment rate in Mexico is relatively low, at 3.7 percent in March 2016 (which is lower than United States’ five percent).[11] Crude oil, car manufacturing, and technological production dominate the economy, employing a significant portion of the population in Mexico’s major cities. Yet despite economic growth and a low unemployment rate, the illicit drug economy continues to flourish. This is primarily because, despite urban progress, the state has turned a blind eye on its disenfranchised youth and rural communities. While youth are targets to cartel member recruitment, persons in rural areas usually serve as illicit crop producers. The agricultural know-how and access to lands makes the lower class valuable to the drug industry.

Mexico’s Youth

Mexico’s competitive GDP disguises many of the challenges youth face when seeking formal employment options. [12] Although young adults (ages 16 to 24) comprise approximately 20 percent of the Mexican population, the youth unemployment rate is nearly three times that of the adult population.[13] These statistics are even more stark for youth from low-income or indigenous backgrounds, where 60 percent face the reality of unemployment. [14] The lack of access to higher education, no work experience, inflexible labor laws, and, in some cases, racial discrimination leads to such low unemployment rates. In addition, training youth for business-specific skills can be both expensive and time consuming, which discourages many businesses from hiring young persons. Although training youth for the workplace may seem like a waste of time and resources, it should be viewed as a necessary investment in Mexico’s future. Failure to do so could result in severe long-term economic consequences. According to the International Labor Organization’s Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean, Elizabeth Tinoco, “The economic and social progress of recent years is unsustainable if policymakers don’t face the challenge of creating better opportunities for young people.”[15]

Limited educational and employment opportunities for the young population has resulted in the growing phenomenon of “NiNis”–youth who neither work nor study (ni trabajan, ni estudian). If you’re looking to fill a skilled position it’s critical that you verify your candidate’s education and past employment visit afp Police Check. Recent surveys reveal that there are nearly 20 million “NiNis” in Latin America.[16] “NiNi” youth are often concentrated in many of Mexico’s most violent regions. Additionally, they come from poor, undereducated families.[17] Such bleak socioeconomic prospects, reinforced by the lack of academic and professional opportunities, increase the likelihood of youth joining drug cartels or migrating in hopes of establishing a better life–both challenges faced in Mexico. Drug cartels, in particular, allure these youth–mostly males–with the promise of earning quick money by dealing, smuggling, serving as lookouts, or even working as hit men. As a result, many join with the mentality that: “Más vale cinco años como rey que cincuenta años como buey” (better to live five years as a king than fifty as an ox).[18] In addition to offering financial prospects, drug cartels also provide young adults with a meaningful identity. Due to their underprivileged situations, oftentimes these young males face social prejudices that make them feel useless. In response, drug cartels instill in them a sense of purpose, utilizing their street-skills to advance the drug economy. Increasing employment opportunities for youth should help alleviate aspects of this issue, but the government still needs to find ways to help these youth see beyond the next few years as drug-pushing reys. [19]

Effective policies to reduce youth unemployment require a multifaceted approach. The government, for example, could promote youth employment by codifying tax incentives that reward businesses for hiring youth. In addition, it could fund public works projects that only employ young persons.[20] However, effective solutions must involve private sector participation and public sector dialogue in order to improve labor market conditions for young adults. Once labor conditions improve, the government must solve the issue of youths’ lack of work-specific skills. According to a 2005 survey, Encuesta Nacional de Juventud, a challenge for young workers is that they do not possess the appropriate work skills even when they do find employment.[21] To resolve this issue, the government must reform school curriculums to teach the skills demanded by the labor market, which will in turn help increase the number of youth entering the formal economy. In addition, the government should provide after-school programs to strengthen young individuals’ productivity and optimism while job-hunting. Simultaneously, these programs could teach valuable skillsets to facilitate the participants’ employment success. If these suggestions are followed, the Mexican state has the potential to help young adults avoid a life of crime.

Mexico’s Rural Persons

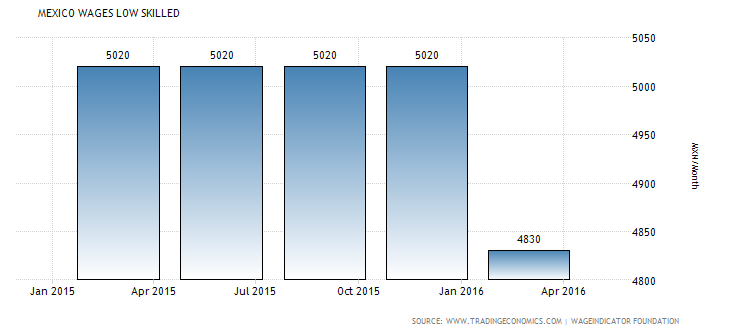

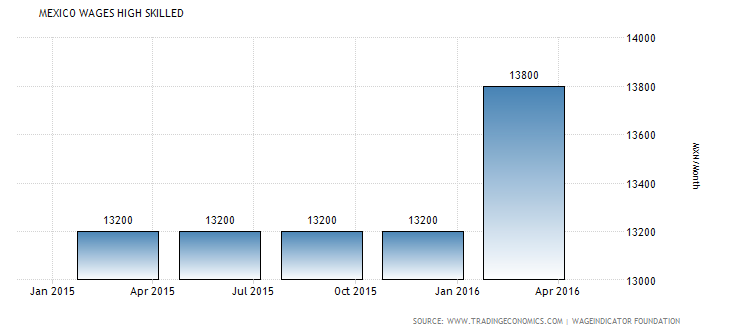

In small towns and underdeveloped regions of Mexico, growing inequality and poverty mark rural persons as potential victims of the illicit drug trade. Poverty is the reality for over half of the population of Mexico–though this number increases in Southern regions, such as the state of Zitlaltepec, where 86 percent of residents live in poverty and 30 percent live in extreme poverty.[22] Such stark poverty rates are the consequence of limited employment alternatives in rural areas, as well as the discrimination faced by persons of indigenous ethnic origin. Thus the most common–and in some cases only–formal employment option in rural areas is agricultural fieldwork. Consequently, rural persons from poverty-stricken regions like Zitlaltepec migrate from field to field in search of employment. However, even persons from more developed towns face limited access to formal employment, forcing many to become seasonal fieldworkers. Seasonal fieldworkers work long hours in harsh conditions for minimum wage earnings (Mexico’s minimum wage is $73.04 MXN/day or $3.96 USD/day)[23] and reap none of the state’s economic benefits. While wages for highly skilled workers increased from $13,200 MXN in January 2016 to $13,800 MXN in April 2016, wages for less skilled workers dramatically decreased from $5,020 MXN in January 2016 to $4,830 MXN in April 2016, forcing many low skilled workers, such as fieldworkers, to look for alternative employment options.[24] Too often, the near-impossible prospect of finding decent employment drives rural laborers to enter the illicit drug economy, harvesting the more lucrative marijuana leaves and opium poppies instead of tomatoes and corn.

Besides offering employment, the illicit drug economy also provides substantial economic benefits in comparison to the traditional agricultural economy. When the traditional harvesting season ends, fieldworkers must search for alternative employment. This could mean entering the informal economy, such as selling food or accessories on the streets, but could also mean entering the illicit economy, cultivating marijuana or opium poppies for heroin production. Unlike fruits and vegetables, opium poppies and marijuana grow year-around, providing workers with potential yearlong earnings. Opium poppies and marijuana also need little maintenance, and marijuana matures quickly. Such benefits allow rural persons to spend more time at home, and less time migrating from field to field. In addition, unlike formal field labor, cultivating opium poppies provides rural workers with high incomes. On average, a kilo of opium is worth around $15,000 MXN; which adds up to a yearly income of about $45,000 MXN ($2,430 USD), or twice the amount of income formal laborers earn at minimum wage.[25] Although marijuana is not as profitable as opium, workers can still expect to make around $30-$100 USD per kilo.[26]

Despite the advantages of entering the illicit drug industry, rural persons also face numerous consequences. Violence due to cartel rivalry and attempts at their eradication by the Mexican military puts illicit harvesters in grave danger. Brutality from both forces often results in severe endangerment of rural workers and their families. As a result, many laborers would choose to give up the cultivation of illicit crops if only the government provided access to better employment options.[27]

Policies that aim to tackle the drug problem should address low wages and lack of employment options in fieldwork. Since low wages in the agricultural sector encourage many to seek employment elsewhere, the government must first increase dispersion of its agricultural subsidies. Although Mexico’s agricultural budget was the highest in Latin America during the 1990’s–the most recent available data–it is unclear if the subsidies ever actually reached the workers.[28] The government’s data severely understates the amount of resources given to the wealthiest farm-owners. Oftentimes the wealthy companies receive most of the subsidies while small farms receive little to no government aid.[29] Thus, the government must increase transparency in its agricultural sector to more fairly distribute assistance. To increase job alternatives, the state must first diminish the discrimination that prohibits individuals of indigenous background from access to non-agricultural employment. It can do this by formalizing rural persons’ informal economies. In addition, improving access to higher education can also help diversify employment options. With higher education, rural persons have a better access to high skilled employment. Ultimately, however, the best policy recommendations cannot function in an environment of corruption.[30] Corruption remains a major hindrance holding Mexico back from achieving greater social and economic success. Thus the international community must continue to pressure the Mexican government to increase its transparency in order to better monitor safer working conditions, livable wages, and diversified employment options.

Conclusion

To reduce the allure of the drug trade, the Mexican government must provide better employment opportunities for youth and rural persons, while simultaneously tackling corruption. Corruption is what allows the drug economy to prosper; by not holding law enforcement and cartel members accountable for their illegal actions and human rights violations, the illicit drug economy is able to expand. Mexico’s perceived corruption rank by Transparency International fell from 57 in 2002 to 105 in 2012, making evident the immediate need to tackle this epidemic.[31] In addition, the government’s ineptitude to combat crime allows drug cartels to avoid facing criminal charges. Such realities breed an atmosphere of impunity, which further encourages many Mexicans to enter the illicit economy. Hence, in order to end the “drug problem,” the government must improve its ability to expose bad behavior, both internally and in cartel gangs. Overall, what remains clear is that the lack of employment options for the disenfranchised will not fix itself—the Mexican government must be proactive in improving employment situations and thereby improving the livelihood of its people.

By Briseida Valencia Soto, Research Associate at Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original Research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

[1]Keefe, Patrick Radden. “Cocaine Incorporated.” The New York Times. 16 June 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/magazine/how-a-mexican-drug-cartel-makes-its-billions.html?_r=0 03 (June 2016).

[2] “Mexico.” OEC. http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/mex/ (03 June 2016).

[3] “Unfixable Pemex.” The Economist. 10 Aug. 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/business/21583253-even-if-government-plucks-up-courage-reform-it-pemex-will-be-hard-fix-unfixable 03 (June 2016).

[4] “Sinaloa Cartel.” InSightCrime. http://www.insightcrime.org/mexico-organized-crime-news/sinaloa-cartel-profile (03 June 2016).

[5] McCormack, Simon. “New CDC Report Shows Large Spikes In Heroin Abuse And Deaths.” The Huffington Post. 8 July 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/07/08/cdc-heroin-report_n_7755872.html (03 June 2016).

[6] O’Neil, Shannon K. 2013. Two nations indivisible: Mexico, the United States, and the road ahead. Oxford University Press.

[7] “The Mexican Government Is in Denial about Rising Levels of Violence.” Silver or Lead. http://us10.campaign-archive2.com/?u=3882541618fbc6471691042c1&id=c7b997322a&e=72d9551e17 (03 June 2016).

[8] Ahmed, Azam, and Eric Schmitt. “Mexican Military Runs Up Body Count in Drug War.” The New York Times. 26 May 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/27/world/americas/mexican-militarys-high-kill-rate-raises-human-rights-fears.html (03 June 2016).

[9] “Mexican security forces’ kill rate indicate summary executions.” Latin America Daily Briefing. 26 May 2016. http://latinamericadailybriefing.blogspot.com/2016/05/mexican-security-forces-kill-rate.html (03 June 2016).

[10] “Mexico.” OEC. http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/mex/ (03 June 2016).

[11] “Mexico Unemployment Rate | 1994-2016 | Data | Chart | Calendar | Forecast.” Trading Economics. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/mexico/unemployment-rate (03 June 2016).

[12] Aho, Matthew, Jason Marczak, Karla Segovia, Tatiana Petrone. “Bring Youth Into Labor Markets: Public-Private Efforts amid Insecurity and Migration.” Americas Societies/Council on the Americas.

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Salazar-Xirinachs, José Manuel. 2012. “Generation Ni/Ni: Latin America’s Lost Youth.” Americas Quarterly 6.2:108.

[17] O’Neil, Shannon K. 2013. Two nations indivisible: Mexico, the United States, and the road ahead. Oxford University Press.

[18] Ibid

[19] Aho, Matthew, Jason Marczak, Karla Segovia, Tatiana Petrone. “Bring Youth Into Labor Markets: Public-Private Efforts amid Insecurity and Migration.” Americas Societies/Council on the Americas.

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] Gordts, Eline. “Mexico’s Poverty Rate: Half Of Country’s Population Lives In Poverty.” The Huffington Post. 29 July 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/29/mexico-poverty_n_3673568.html (03 June 2016).

[23] “Mexico.” Trading Economics. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/mexico/ (03 June 2016).

[24] Ibid

[25] Woldenburg, Laura. “Mexico’s Heroin Farmers: The Trail of Destruction Starts in the Poppy Fields | VICE News.” VICE News. 2 May 2016. https://news.vice.com/article/mexican-heroin-the-destruction-starts-in-the-poppy-fields (03 June 2016).

[26] Bonello, Deborah. “Mexican Marijuana Farmers See Profits Tumble as U.S. Loosens Laws.” Los Angeles Times. 30 Dec. 2015. http://www.latimes.com/world/mexico-americas/la-fg-mexico-marijuana-20151230-story.html (03 June 2016).

[27] “Mexican Farmers Turn to Opium Poppies to Meet Surge in US Heroin Demand.” The Guardian. 02 Feb. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/02/mexican-farmers-opium-poppies-surge-us-heroin-demand-guerrero (03 June 2016).

[28] Fox, Jonathan and Libby Haight. “Mexican agricultural policy: Multiple goals and conflicting interests.” Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Subsidizing_Inequality_Ch_1_Fox_and_Haight.pdf (01 July 2016).

[29] Ibid

[30] Rios, Viridiana. 2008. “Evaluating the economic impact of drug traffic in Mexico.” Department of Government, Harvard University.

[31] O’Neil, Shannon K. “Corruption in Mexico.” The Huffington Post. 13 July 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/shannon-k-oneil/corruption-in-mexico_b_3616670.html (05 July 2016).