Coming Together To Strike Out On Their Own? Challenges, Change and Colonial Legacy in the Caribbean

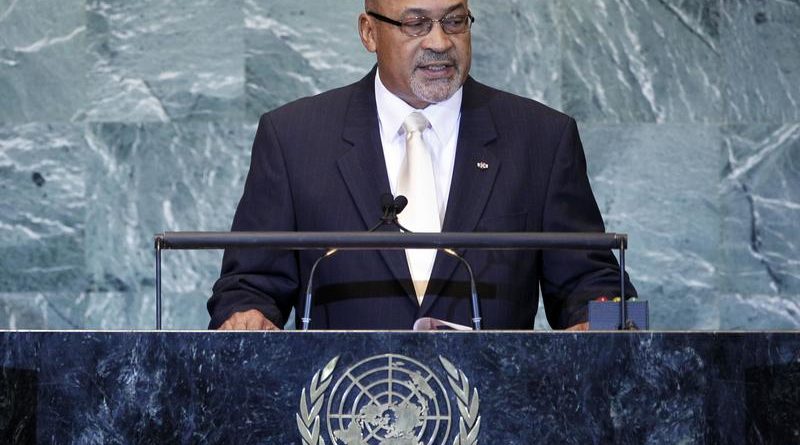

On July 4, 2012, the controversial President of Suriname and outgoing chairman of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) H.E. Desiré Delano Bouterse commented on intra-regional cooperation in the Caribbean, stating that: “Unity and solidarity are the real cornerstones towards our success….only unwavering solidarity and determination must be the driving force in our community as well as in our region.”[1] The sovereign states of the Caribbean are long used to the strategic maneuvering and vagaries of larger neighbors in the competition for geopolitical influence. Bouterse acknowledged this condition in the same speech, arguing that “[The Caribbean’s] inter linkage within the framework of interregional cooperation is being tested by the accelerating development, which we have witnessed within our region over the past months.”[2]

Sandwiched between increasingly influential Latin American nations to the south and the United States in the north, the potential for Caribbean leaders to find themselves pulled in different directions by international and regional diplomatic, political, and economic forces is great. With the United States undergoing a somewhat shaky recovery from recession and emerging economies such as China looking to establish new markets, developing influence in the Caribbean region is perhaps more desirable now than it has been at any time since the end of the Cold War. Further complicating the relationships between Caribbean states and other nations in the Western Hemisphere are the strong diplomatic links (based on historical ties) maintained with the old European colonial powers. This complex and interrelated series of associations presents Caribbean leaders with various difficulties as regional nations attempt to forge their own identity and achieve political autonomy.

There are signs, however, that regional states are keen to change this special relationship with former colonial powers, to assert their independence and begin to remove anachronistic vestiges of colonial governance in order to cement an individual identity. Moreover, there are indications that Caribbean nations are beginning to collaborate with one another more frequently and more effectively, tackling issues that can be better addressed through collective efforts. While many states in the region will undoubtedly remain somewhat connected to their old historical ties, there appears to be a determination amongst Caribbean leaders to face shared problems on a more independent footing.

The sovereign states of the Caribbean should not, of course, be treated as a homogenous group. There are vast differences in size, relative prosperity, economic development, and political culture, as well as governance capabilities between different nations in the region. Furthermore, as independent entities with differing historical legacies, the relationships between individual Caribbean states and international neighbors also vary. Cuba’s relationship with the United States, for example, is vastly different from that of Barbados. But while it is important to recognize the differences between nations in the region, there is little doubt that many similarities exist between them. Indeed, the formation of CARICOM in 1973 was a tacit recognition of these similarities. But the extent to which CARICOM projects have attempted to foster true Caribbean integration in its near four-decade existence is nonetheless debatable, and the structure of the organization has been viewed by some as designed to simply allow leaders to increase the effectiveness of national policies through a regional framework.[3]

Recession and Remittances

The global economic recession had a withering impact on developing Caribbean economies. Reliant upon more advanced economies and very susceptible to conditions found in the U.S. market, Caribbean economies grievously suffered as demand for goods and services such as tourism, bauxite, and off-shore financial services contracted.[4] A decrease in remittances from migrant workers, which pumps valuable funds back into Caribbean economies, as well as a reduction in foreign direct investment—both effects of the global economic downturn—demonstrate the general vulnerability of the Caribbean nations to external shocks.[5] Many Caribbean economies are heavily dependent on one or two industries for the bulk of their exports; bananas and sugar in the agricultural sector, and tourism in the services sector for example.[6] Furthermore, many Caribbean nations are somewhat reliant on foreign economic aid. Between 1980 and 2010, the U.S provided almost $14 billion USD in foreign aid (almost 95% of which was economic assistance and the rest military assistance) to countries in the region.[7]

European nations with strong colonial links to the Caribbean also provide foreign aid to the region. In fact, despite feeling the squeeze of a global recession and the Eurozone crisis, the UK foreign aid budget for the region increased from £13.3 million in 2010-2011, to £18.8 million in 2011-2012.[8] In the past, the majority of economic aid has been provided for disaster relief, the alleviation of poverty, economic development, and the strengthening of governance, the rule of law, and health services in Caribbean nations. Many in the region remain reliant on such aid and on foreign investment from the U.S. and other foreign sources. Shifts in global economic trends are providing Caribbean leaders with an opportunity to look outside their traditional trading partners to new investment powers. But seeking out these partners illuminates some of the problems faced by small nations caught between larger, more powerful neighbors.

Chinese Financial and Political Maneuvering

China’s immense sovereign wealth and booming economy has allowed it to invest huge amounts of capital in commodities from countries around the world. Despite current indications that growth is beginning to abate, the policy of aggressively outspending competitors has recently allowed Beijing to acquire vast tracts of land, natural resources, and desirable agricultural and extractive commodities in Latin America.[9] The Caribbean region has seen a substantial increase in foreign direct investment from China in the past five years. According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, foreign direct investment in Caribbean countries by Chinese firms amounted to almost $7 billion USD in 2009, a massive increase from the $1.7 billion USD invested in 2004.[10] In February 2010, President of Jamaica Bruce Golding and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao signed an agreement that allocated $500 million USD of Chinese capital investment to housing, road and other construction projects on the island.[11] Other large Caribbean infrastructure projects which received (or will receive) relatively massive injections of Chinese cash and investment funds include the construction and operation of a USD $1 billion container port in Freeport, the Bahamas, the building of the Prime Minster of Trinidad and Tobago’s official residence, and the Bosai Minerals Group’s purchase a USD $100 million majority stake in Omai Bauxite Mining in Guyana.[12]

On a purely material level, China’s interest in the Caribbean appears somewhat contradictory. Beijing has invested heavily in a region with few natural resources, little relative capacity for growth, and a need for substantial economic development. The investment is, however, likely designed at least in part to achieve political ends. The Chinese are flexing their economic muscles in an area previously dominated by Washington, a region that has strategic significance due to its geographic proximity to the American homeland.

Furthermore, the Chinese government has used its financial power to achieve political diplomatic goals over the issue of Taiwan. The use of dollar diplomacy to persuade countries that recognize and maintain diplomatic ties with Taiwan to abandon this position has been Beijing’s preferred tactic in the Caribbean for more than a decade. In 2004 Dominica switched its allegiance to Beijing in return for grants worth $122 million USD, and in 2005 Grenada cut ties with Taiwan in a similar deal.[13] When the government of St Lucia restored relations with Taiwan in 2007, ten years after it had cut ties in return for economic aid, Beijing denounced the island nation for “brutal interference in China’s internal affairs.”[14] The future of Cuba, China’s closest Caribbean ally, is also likely a factor in Beijing’s increasingly active move into the Caribbean.

The death of either of the Castro brothers is likely to generate some form of political instability and may ultimately see the end of Communist Party rule as we know it. It would be advantageous for Beijing to be in a position to exercise some influence over the course of succession, or failing that, to have some leverage to be able to maintain a strategic stance in the region. Washington, of course, will have its own agenda regarding the future of the island. These interrelated political and strategic considerations of larger nations may therefore play a significant role in shaping the Caribbean.

The Caribbean and the Malvinas/Falklands

The ongoing dispute between the UK and Argentina over the Malvinas/ Falkland Islands is an issue that at first glance should not have a persistent impact on the Caribbean. However, as with Chinese investment in the region, it is an issue that demonstrates the difficult position in which leaders of Caribbean nations find themselves when dealing with traditional and new partners. Many Caribbean governments maintain a close relationship with London; Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago are all members of the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organization consisting of independent member states formerly part of the British Empire.[15] The sovereignty of the Malvinas/Falkland islands, however, is an ongoing subject that has split opinion amongst Caribbean governments and provides an interesting case study of the complicated diplomatic positions that the region’s leaders are currently taking in relations with the main protagonists in the dispute.

The lack of unanimity on the Malvinas/Falklands issue is not surprising given the differences between countries in the region. The Caribbean response to the Argentine government’s recent attempts to address the issue under President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s imprimatur has been somewhat spotty, if not contradictory. At the January 2012 UK-Caribbean forum, ministers in attendance agreed to “support the principle and right to self-determination for all people, including the Falkland Islanders, recognizing the historical self importance of self determination in the political development of the Caribbean.”[16] In February however, Argentine Foreign Minster Hector Timerman announced that two Commonwealth members, Antigua and Barbuda as well as St Vincent and the Grenadines had agreed to support Buenos Aires over the Malvinas/Falklands by blocking any ships flying a Falklands flag from docking at their ports.[17] The agreement, secured at the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) summit, also saw Dominica and Cuba support the blockade.[18]

Ideologically, ALBA is dominated by the politics and presence of left-leaning figures such as Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, and Rafael Correa of Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador respectively. Thus, it strongly advocates the rights of Latin American and Caribbean nations to seek self-determination, territorial sovereignty, and the ability to operate their societies free from external interference. While Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba, and Ecuador’s support for the Argentine position was not surprising, Antigua and Barbuda and St Vincent and the Grenadine’s decision seemed to shift the diplomatic direction of the islands. Caribbean economists have suggested that the financial resources available to members of ALBA are far greater than that provided by the CARICOM Development Fund. This is an attractive incentive for Caribbean nations to carefully consider applying for ALBA membership.[19]

Similar to the Taiwan issue, the temptation of increased financial resources along with the promise of greater development and economic independence that these resources could provide may be just enough to persuade Caribbean nations to alter their position on the Malvinas/Falklands. Therefore, this monetary incentive could potentially have an impact on their long-term relationship with the British government and economy. St Lucia has supported the right of the Malvinas/Falkland Islanders to self-determination since 1985. But at the February 2012 ALBA summit it was granted special guest membership to the organization alongside Suriname, a step prior to full entry.[20] As St Lucia moves towards full membership in ALBA, its current position on the conflict is expected to come under intense scrutiny from its fellow member nations.

Less Than Meets the Eye

Yet the position of the Caribbean nations on the issue remains contradictory and confused. Less than a week after Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs Hector Timerman’s blockade announcement, the governments of Dominica and Antigua and Barbuda disassociated themselves from the shipping ban. A Dominican government statement commented, “[Dominica] has not granted its support to any call for the region to ban ships with the colonial flag imposed on the Malvinas from entering its ports, as stated in the said declaration. Dominica therefore disassociates itself from statements regarding the banning of ships carrying the flag of the Falklands from entering its ports.”[21] The seemingly oscillating position of Dominica and Antigua and Barbuda on the blockade demonstrates how Caribbean nations, in the search for regional independence and prosperity, are being pulled between their Latin American neighbors and historical European and North American colleagues.[22]

Legal Reform and Strengthening of Governance

Although they face difficult and varying geopolitical currents, there are indications that Caribbean nations are in fact making measured progress toward greater independence through collaborative regional governance initiatives. There is a fundamental recognition among the region’s political leaders that greater independence requires enhanced governance capabilities. Strengthening the ability of Caribbean governments to effectively administer their social, economic, and security policies is critical to the affected nations that wish to move away from the status quo. Conversely, Caribbean states are still somewhat reliant on the more developed and richer governance structures of their larger, more powerful international partners. Working collectively, Caribbean nations have repeatedly learned that they can better overcome limitations born out of geographic disparity.

The development of law and legal process is an area that has seen some meaningful progress. Perhaps the best example of this is the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), based in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, that was created by means of a February 2001 agreement initially signed by ten CARICOM states, and which was inaugurated in April 2005.[23] Founded to act as the supreme judicial organ in the Caribbean, the CCJ aims to assist the development of Caribbean law and “provide for the Caribbean Community an accessible, fair, efficient, innovative and impartial justice system built on a jurisprudence reflective of our history, values, and traditions while maintaining an inspirational, independent institution worthy of emulation by the courts of the region and the trust and confidence of its people.”[24] Most importantly, however, the CCJ is also designed to be a watchdog for the Caribbean community as its final court of appeal.[25] For many Caribbean nations the highest court of appeal prior to the establishment of the CCJ was the UK Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The establishment of dedicated Caribbean jurisprudence relevant to Caribbean islanders, as opposed to relying on the legal traditions of the UK, is a pertinent example of a collaborative initiative designed to strengthen the implementation of a legal code throughout the region.

The transition from Privy Council to the CCJ has been far from smooth, however, and the majority of the twelve states that agreed to adopt the CCJ have yet to do so. As the CCJ is predominantly based on the British justice system, it is expected that Suriname and Haiti, whose legal traditions have their foundations in the Dutch and French legal systems respectively, will have the most difficulty with cases sent to the CCJ. Even ex-British colonies with legal systems that sprung from the British model have not fully embraced the CCJ. As of April 2012, Trinidad and Tobago President Kamla Persad-Bissessar announced that legislation would be brought to Parliament to replace the British Privy Council with the CCJ.[26 ] This legislation can be seen as somewhat piecemeal however, as the CCJ will become the final appellate court only in criminal matters; civil matters will still be heard before the London-based Privy Council.[27] This split in jurisdiction may indicate a lack of confidence on the part of the Trinidadian government about the ability of the CCJ to undertake the caseload of both civil and criminal matters in its current guise.[28] It also raises questions about the legitimacy of the court in the eyes of Caribbean governments. Although the process of adopting the CCJ is certainly not unproblematic, this is the kind of cooperative initiative that Caribbean governments should be looking towards in order to enhance their governance capabilities and end the reliance on the institutions of other nations.

Caribbean Republicanism and the Colonial Legacy

Removing the last vestiges of the colonial legacy in the Caribbean, even those that are largely symbolic in nature, is another important step in affirming the self-determination and core independence of nations in the region. Currently, the Caribbean nations that are a part of the so-called ‘Commonwealth Realm’ share Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state.[29] The fact that a British monarch maintains a position as the head of state of a string of nations over 4,000 miles away from London is somewhat of an anachronism, particularly when the Queen is bereft of constitutional power. Almost immediately after winning a landslide election victory in January of this year, Jamaican Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller announced her intention to loosen the symbolic colonial ties with Britain and make the transition into a republic by replacing the Queen with a Jamaican-born president.[30] Jamaica, the largest of the English-speaking Caribbean nations in the Commonwealth Realm, recently celebrated fifty years of independence and fully repatriating Jamaica’s sovereignty would be, according to some, a fitting way to mark the anniversary.[31]

Simpson Miller’s republican proclamation is latest indication of the growing republican sentiment amongst Commonwealth Caribbean nations. Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago have already dropped the Queen as head of state, and Barbados has put in place the means for a referendum to be held on the issue when the government deems it appropriate.[32] Establishing Caribbean republics with its own heads of state is viewed by many as a necessary psychological and constitutional step in further cementing a sense of political maturity, legitimacy, and autonomy. This drift of republican sentiment in the Caribbean may also ultimately help to foster a broader Caribbean identity, and encourage closer cooperation between nations of the region.

Conclusion

What the future holds for the nations of the Caribbean and the region as a whole is not exactly clear. As the region prepares to cope with its immediate future, larger nations in the Western Hemisphere (including the U.S.), Europe, and Asia are likely to continue to exert varying forms of influence over the Caribbean through bi- and multilateral political, economic and security arrangements in order to achieve their broader geopolitical aims. The dependence of many Caribbean nations on maintaining good relations with its existing neighbors and partners, particularly regarding economic prosperity, will continue in this capacity for many years. But Caribbean leaders can continue to develop the strength of their institutions and governance capabilities while removing the last vestiges of their dependent aspects. Moreover, they should develop relationships with new international partners while still maintaining mutually beneficial links with traditional allies, and make a more concerted effort to collectively address newly developing Caribbean issues on a multilateral basis through joint initiatives. Within these parameters, they will place the region in a far stronger position to determine the collective course of their futures.

While this concept is neither new nor particularly revelatory, indications are that progress is beginning to be made, and that a constructive Caribbean political tradition removed from the colonial legacy is beginning to develop. In an uncertain and changing geopolitical climate, having the ability and conviction to choose which partners to ally with on a utilitarian basis within its own terms, rather than being pulled along by shifting and broader global political currents, would be a huge advantage to the Caribbean community. Caribbean leaders must recognize the importance of continuing the current process of cooperation, integration, and political development, since only through coming together will the region ultimately be able to better strike out on its own.

Sources:

[1] Bouterse, H.E. Desiré Delano. Statement by the Outgoing Chairman to the Caribbean Community H.E. Desiré Delano Bouterse, President of the Republic of Suriname, on the Occasion of the Thirty-Third Regular Meeting of the Conference of the Heads of Government 4 July, Gros Islet, Saint Lucia. CARICOM Secretariat Press Release 174/2012. 4 July 2012. http://www.caricom.org/jsp/pressreleases/press_releases_2012/pres174_12.jsp?null&prnf=1

[2] Ibid.

[3] Payne, Anthony and Paul Sutton. Charting Caribbean Development. Gainesville:

University of Florida Press. 2001. p. 174.

[4] Downes, Andrew S. The Global Economic Crisis and Caribbean States: Impact and Response. Presentation at Commonwealth Secretariat Conference on the Global Economic Crisis and Small States London, July 6-7, 2009.

[5] A fall in remittances in particular can have a significant impact on the economies of states such as Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana, for whom remittances were estimated in 2009 to comprise 19.4, 20, and 23.5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) respectively

[6] United States International Trade Commission. Caribbean Region: Review of Economic Growth and Development. USITC Publication 4000. May 2008.

[7] Meyer, Peter J. and Sullivan, Mark P. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: Recent Trends and the FY 2013 Appropriations. Congressional Research Service. June 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R42582.pdf

[8] Blight, Garry and Provost, Claire. The Future of UK aid. The Guardian Data Blog. 5October 2011.

[9] Bradsher, Keith, “After Barrelling Ahead in Recession, China Finally Slows,” The New York Times, May 24 2012. It is not only Latin America where China has invested capital. Beijing has also spent huge amounts acquiring natural and other resources in Asia and Africa

[10] Fieser, Ezra, “Why is China Spending Billions in the Caribbean,” Global Post, 22 April 22, 2011. http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/americas/110325/china-caribbean-investment-tourism?page=full#.

[11] Jamaica Gleaner, Jamaica, “China sign US$500 million Investment Pact,” Jamaica Gleaner, February 5 2010.

[12] Fieser, Ezra, “Why is China Spending Billions in the Caribbean,” Global Post, 22 April, 2011. http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/americas/110325/china-caribbean-investment-tourism?page=full#. Interestingly, the Bosai Minerals group purchased their stake in Omai Bauxite Mining from the government of Guyana.

[13] The Economist. A Chinese Beachhead? New Investors on America’s Doorstep. The Economist. 10 March 2012. http://www.economist.com/node/21549971

[14] Daremblum, Jaime. China’s Caribbean Adventure. The Weekly Standard. 18 June 2012. http://www.weeklystandard.com/blogs/china-s-caribbean-adventure_647421.html

[15] Commonwealth Foundation. Commonwealth Countries. Commonwealth Foundation. http://www.commonwealthfoundation.com/Aboutus/TheCommonwealth/Commonwealthcountries

[16] Ibid.

[17] Goni, Uki and agencies. Caribbean countries back Argentina over Falklands with Blockade. The Guardian. 6 February 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/feb/06/falklands-argentina-britain-blockade .

[18] Henderson, Barney. Hugo Chavez says Venezuelan troops would fight with Argentina over the Falklands. The Telegraph. 6 February 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/falklandislands/9063065/Hugo-Chavez-says-Venezuelan-troops-would-fight-with-Argentina-over-Falklands.html

[19] Richards, Peter. Caribbean Divided on Malvinas/Falklands Blockade. Inter Press Service News Agency. 9 February 2012. http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/02/caribbean-divided-on-malvinas-falkland-blockade/

[20] El Universal. ALBA summit ends with entry of guest countries. El Universal. 6 February 2012. http://www.eluniversal.com/nacional-y-politica/120206/alba-summit-ends-with-entry-of-guest-countries

[21] MercoPress. Dominica disassociates itself from barring Falkland’s flagged vessels from its ports. MercoPress. 15 February 2012.

[22] There is of course, an alternative interpretation of this situation. Some may argue that Caribbean leaders are, in fact, attempting to assert their independence by maintaining their own position on the Falklands-Malvinas issue, despite the solidarity of the rest of the ALBA nations and the pressure they place on the smaller nations that wish to join.

[23] Caribbean Court of Justice. The CCJ: From Concept to Reality. Caribbean Court of Justice. http://www.caribbeancourtofjustice.org/about-the-ccj/ccj-concept-to-reality

[24] Caribbean Court of Justice. Mission and Vision. Caribbean Court of Justice. http://www.caribbeancourtofjustice.org/about-the-ccj/mission-vision

[25] Ibid. ; The Supreme Court. The Supreme Court and Europe. The Supreme Court. http://www.supremecourt.gov.uk/about/the-supreme-court-and-europe.html

[26] Ramdass, Anna. Goodbye Privy Council. Trinidad Express. 25 April 2012 http://www.trinidadexpress.com/news/GOODBYE__PRIVY_COUNCIL-148989575.html

[27] Ibid.

[28] In a surprising recent development, Honduras (the country with the highest murder rate in the world) may become the latest country to send cases to the Privy Council as the final appellate court. The Honduran government to create several regional semi-independent city-states with improved governance structures in order to attract greater business investment and create employment. These development zones, known as La Región Especial de Desarrollo (RED) are to be backed by international partners in order to improve governance in the RED zones. Mauritius, a member of the Commonwealth that still uses the Privy Council in Westminster as a final court f appeal, has agreed to guarantee the legal framework of the courts in the RED development zones. Therefore, cases originating in Honduras could progress through Mauritian appeal courts and eventually reach the Privy Council in London for a final decision. For more see:

Bowcott, Owen and Wolfe-Robinson, Maya. Honduras may appeal to London courts. The Guardian Online. 22 July 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/law/2012/jul/22/honduras-london-courts?newsfeed=true

[29] These nations are: Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines. There are also several non-Caribbean nations which are a part of the Commonwealth Realm and count the British Queen as their head of state.

[30] Harding, Luke. Jamaica to become a republic, prime minister pledges. The Guardian Online. 6 January 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jan/06/jamaica-republic-prime-minister

[31] Davies, Caroline. Jamaica’s PM welcomes Prince Harry – but wants to replace his grandmother. The Guardian Online. 6 March 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/mar/06/prince-harry-jamaica-visit-republic

[32] Tovrov, Daniel. Jamaica’s New Prime Minister Wants Republic, Cut Ties to UK Monarchy. International Business Times. 6 January 2012. http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/277875/20120106/jamaica-s-new-prime-minister-republic-cut.htm