The Lure of Cuban Energy Independence: One Twist After Another

On May 29 during a press conference presenting Repsol’s four-year strategic plan, the company’s president, Antonio Bufrau, announced that the Spanish oil giant will almost certainly stop prospecting for oil in Cuban territory after a costly well it drilled turned out to be dry. This recent disappointment parallels the 2004 finding by Repsol that established that its explorations on the northwest coast of the country would not yield commercially viable quantities of oil. After spending $150 USD million in explorations throughout the country, Repsol is likely to turn its attention to more profitable fields in countries such as Brazil and Angola.

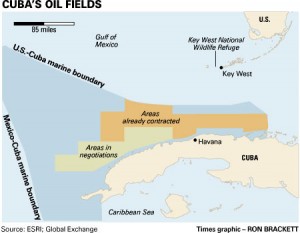

With the conclusion of the Spanish company’s operations on the island, the Cuban dream for energy independence could vanish, especially considering that the leased platform Scarabeo 9,is the only one allowed to operate offshore in the Cuban Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), an area of 112 square kilometers in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Repsol’s initial plan was to move the platform to a different location unless another company stepped up to lease the oil rig, at a cost of $150,000 USD per day. The Spanish company, in consortium with Statoil of Norway and the Indian ONGC, held an option to drill another well in the waters of the Cuban EEZ. But Brufau was terse in rejecting the arrangement, stating that the company preferred to concentrate its search for oil in Angola and Brazil.

Unsurprisingly, Cuba does not want to abandon its quest for oil. In an official statement, the Cuban government affirmed that Repsol’s decision does not eliminate the potential of the Cuban EEZ. He asserted that the EEZ could eventually become one of the largest reservoirs of oil production worldwide, given the high estimates regarding the country’s yet to be discovered hydrocarbon reserves. A U.S. geological survey, for instance, projects a presence of approximately 5 billion barrels in oil reserves in the country.(1) In light of such figures, this dry well could be considered isolated and not totally symptomatic. Cuban oil expert at the University of Texas Jorge Piñón affirms that two unprofitable wells are not indicative of the presence or lack of oil deposits in Cuba.(2)

The press release by the Cuban government clarifies that the exploration will continue and that the semi-submerged platform Scarabeo 9 (previously utilized by Repsol) has now been moved to the Catoche 1X sector, located north of the province of Pinar del Rio. The Malaysian oil company Gulf PC is operating in the new drilling site in cooperation with the Russian company Gazpromneft. Once this drilling is completed, the Scarabeo 9 will be moved again, this time further to Cabo de San Antonio 1X, and another round of drilling will likely commence under the supervision of the state-owned Venezuelan oil company PDVSA (Petroleos de Venezuela SA), which will hold the master lease on the platform.(3)

The Spanish company’s decision to leave Cuba can perhaps be best understood as a political move made by the country. At first glance, Repsol’s attitude may appear to reflect the new foreign policy now being implemented by the freshly elected right-leaning Spanish government led by Mariano Rajoy. However, it has become increasingly likely that the main reason for this withdrawal is a strategic response by the Spanish company after the Argentine government nationalized YPF, Repsol’s former affiliate in Argentina. Repsol may have been pushed to make this decision after Cuba had lauded and supported the oil company’s seizure by Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. As was easily predictable, the Raul Castro administration is in support of the Argentinian takeover of YPF, and even though this move seems consistent with the ideology of Cuban leaders, it ended up being a risky and counterproductive step for Cuba. Repsol’s move came as a real shock, disappointing not just President Raul Castro’s dream of energy independence for the Island, which now heavily depends on guaranteed supplies from Venezuela (100,000 barrels per day), but the country’s need to revitalize its economy as well.

The Castro administration’s desperate pursuit of energy security is also motivating the country to develop renewable energy alternatives. In a recent note published in the official government media outlet Cubadebate, the administration made public its intention to increase Cuban renewable energy production from 3.8 percent to 16.5 percent—a 12 percent increase—over the next eight years.(4) This is expected to be achieved using mainly sugarcane and other sources of biofuel, but also through hydraulic, solar, and wind sources. The government also is considering expanding production of biogas by 10 percent by the end of 2013.

This new declaration, however, clearly shows the dogged will of the Caribbean country to achieve energy independence. As Robert Zoellick, outgoing president of the World Bank, remarked, it is obvious that if Venezuela cuts its subsidies to Cuba, the regime would find itself in some sort of precarious outcome, hence the need for new energy sources.(5) However, the plan as outlined by Cuban strategists seems unclear. In fact, Cuba appears to be moving down two very different and contradicting paths; one is more classical in the hunt for black gold, while the other is based on sustainable and efficient growth. Of course, if Cuba finds oil in its EEZ, the discovery will definitely enhanced its geopolitical outlook. But a cost-benefit analysis has to be made by the Castro government. Cuba has great potential to develop an energy plan that is both cheaper and environmentally sustainable, and now is the time for it to unlock that potential.

To view citations, click here.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.