Suriname: Justice Under Fire

Last month the judge overseeing the trial to determine the full extent of Surinamese President Dési Bouterse’s involvement in the 1982 December Murders put the proceedings on hold. In light of the National Assembly’s retroactive Amnesty Act granting immunity to Bouterse and his political henchmen, whether the Public Prosecutor’s office can legally carry on the trial is now uncertain. As Stabroek News of neighboring Guyana reported last Wednesday, the government has pressured the trial’s judges to bury the case by threatening their safety. The act, an affront to justice, is part of a long pattern of abuses by Bouterse and his colleagues. Regrettably, the suspension of the trial likely means that the Public Prosecutor’s office will be unable to obtain a guilty verdict against Bouterse. Meanwhile, relatives of the December Murder victims and the Surinamese nation await the justice that has been delayed for the past 30 years.

On December 8, 1982, military policemen snatched 15 men from their beds, most of them civilians, placed them on a bus and then murdered them after conspiracy charges were lodged against them. The victims were all members of the Suriname Association for Democracy, a vocal group critical of the growing relationship between the Surinamese military government and Cuba. The group, according to Bouterse and other officials, was plotting to overthrow the government on Christmas Day. While Bouterse and other government officials initially used this story in an attempt to justify the extrajudicial killings, the state later conceded that it acted without conducting adequate investigations. In the immediate aftermath of the murders, Bouterse utilized the high level of public confusion to announce that his military government would be imposing a curfew, closing down universities, restricting the freedom of assembly, and closing Suriname’s borders, effectively ushering in an era of conflict and military dictatorship in Suriname. Following the December Murders, the prime minister and cabinet resigned in protest, indicating discontent within the government regarding Bouterse’s abuse of power. An investigation finally began in 2008, with Bouterse as the prime suspect. Though he eventually accepted “political responsibility” for the murders, he continues to deny any direct involvement.

Unfortunately, this tragic and violent event is one of many in the political career of Dési Bouterse and the country’s short history. The often-overlooked South American country won independence from the Netherlands in 1975 and operated under a democratically elected government until February 25, 1980, when Bouterse led a military coup d’état. As a result, he assumed the post of chairman of the National Military Council (NMR), a group of eight non-commissioned officers who effectively functioned as the Surinamese government for the next six years. During its first year in power, the NMR implemented a law enabling the government to rule by decree, thereby suspending all existing laws as well as civil, political, and social rights of the small Surinamese populace. In the following years, extreme violence and political instability crippled the nation while power gradually became concentrated in the hands of Bouterse and the military leadership.

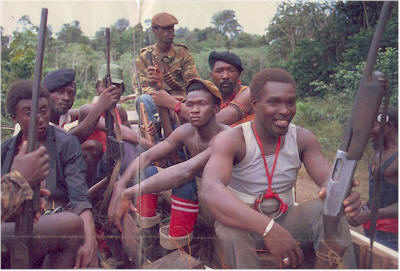

From 1986 to 1992, civil war gripped the young nation. Bouterse and his forces engaged in continual combat with the Surinamese Liberation Army, a guerrilla group better known as the Jungle Commando. While Bouterse charged the guerrillas with plotting to undermine national stability and peace, he was, allegedly, simultaneously vying for control of the lucrative cocaine trade. Meanwhile, an ethnic group known as the Maroons comprised much of the opposition, who fought for return to democracy under the leadership of Bouterse’s former bodyguard and comrade in arms Ronnie Brunswijk. In what was perhaps the war’s most inexplicably violent act, the military government executed more than 40 people, mostly women and children, and burned the village of Moiwana a Maroon stronghold on November 29, 1986. Three years after the attack, demonstrative of the impunity under which the dictatorship freely operated, Bouterse issued a statement admitting that the murders had been committed by the military under his direct orders. Only after being targeted by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR), the Surinamese government finally made a public apology to the victims’ families in 2006, claiming responsibility for the deaths and paying compensation to the survivors. Neither Bouterse nor any other officer involved was ever punished for the horrific act of genocide.

In 1988, the elected president, Ramsewak Shankar, signed a peace accord with the guerrillas. Bouterse, however, rejected the treaty, opting instead to continue the war. In 1989, the IACHR issued a human rights report on Suriname with numerous complaints regarding the administration’s violations of the right to life and freedom of speech, among other abuses. In 1990, Bouterse led yet another coup, ousting President Shankar and further propagating instability and violence within Suriname.

In 1997, the Dutch government issued a warrant for Bouterse’s arrest on drug smuggling charges. However, the Surinamese president at the time, Jules Wijdenbosch, was one of Bouterse’s allies and refused to extradite him. Having received no cooperation from the Surinamese government, the Dutch government convicted Bouterse of the drug smuggling charges in absentia two years later.

In 2008, Bouterse and 25 others were finally indicted on charges of murder for their involvement in the 1982 December Murders. In spite of a violent past and his status as a murder suspect, Bouterse has enjoyed considerable political success. He formed the Mega Combination Coalition in the National Assembly, which propelled him to the presidency in 2010. By allying himself with former enemy Ronnie Brunswijk, Bouterse secured 23 out of 51 votes—just enough for a victory.

The current Bouterse administration, while not as violent as his infamous six-year dictatorship, has been characterized by the same corruption and nepotism of the past. Following his election, Bouterse gave his wife a salary for her duties as first lady and appointed his son, convicted of drug and weapons trafficking in 2005, to a commanding position in a counterterrorism unit. Rather than downplay his problematic past, Bouterse continued his raffish lifestyle, celebrating his violent 1980 coup d’état by designating February 25, its anniversary, as a national holiday.

At immediate issue is the Amnesty Act passed by the National Assembly, which applies to all crimes committed between 1980 and 1992. The amnesty it provides not only conveniently covers the December Murders, but also all the other human rights abuses that took place under Bouterse’s rule and throughout the civil war, including the Moiwana Massacre. Bouterse and several of the other defendants are requesting that the trial be suspended in light of this law, and as a result, it has been adjourned until the law undergoes further review.

This adjournment, however, creates a constitutional catch-22. Over the past four years, the fate of Bouterse and his partners has been held up in judicial proceedings. In order for the trial to reconvene, a constitutional court must decide whether a judge can grant amnesty ex post facto. Setting aside this painfully slow application of due process, the real challenge in bringing Bouterse to justice lies in the fact that the constitutional court that would conduct the hypothetical review does not yet exist, and its creation would inevitably be fraught with corruption. Bouterse, who as president is responsible for appointments, could easily stack the court with sympathizers who would most certainly approve the amnesty law, thereby exonerating him and his cohorts.

Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the IACHR, and the International Commission of Jurists have condemned this affront to justice. Likewise, the Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA) condemns the Amnesty Act and urges the Surinamese Judges and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to resume the trial. In order to achieve justice for victims of the December Murders and Bouterse’s other abuses, and for Suriname to move forward from its violent past, due processes is of the utmost importance. Increased pressure from the international community will prove essential in encouraging Suriname to honor justice and avoid setting a dangerous precedent that could allow for more violence from a leader with an already disgraceful human rights record. The Surinamese judicial system must recognize the significance of the decision for the victims’ families as well as for all Surinamese citizens. COHA urges the Surinamese court to work to prevent further violence and erase the stain on democracy that is synonymous with the presidency of Dési Bouterse.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution.

Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

This analysis was supported by the Clough Center for Constitutional Democracy, Boston College.