2016 Appropriation Bill Highlights US Support for Central America and Colombia

By: Santiago Baruh and Miguel Salazar, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

The 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed by the United States Congress on December 18, allows for the funding of multiple domestic and international U.S. programs for the next fiscal year. The approval of these measures is a continued show of support for Washington’s strongest Latin American ally, Colombia, and comes as surprisingly good news for Central America’s Northern Triangle—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—as the bill in question will allow the State Department to appropriate 750 million USD to the region. This figure amounts to almost 75 percent of the request made in the ‘U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America’, included in the Foreign Operations Budget for FY2016. This is a triumph for the State Department, as analysts had previously stated that neither the House nor the Senate seemed inclined to fully fund it; the House was said to be planning to allocate no more than 296.5 million USD, whereas Senate proposed to authorize the appropriation of 675.3 million USD. Moreover, while the appropriation of more funds is a victory in and of itself, it is enhanced by beneficial provisions within the bill.

As mentioned in prior COHA articles, the Obama Administration’s 2016 plan differs from previous strategies because it shifts the focus away from security initiatives (such as the Central American Regional Security Initiative) towards measures that target the structural issues that up to now have crippled the Northern Triangle. This change is evident in the bill’s wording, which stipulates that 75 percent of the funds can only be appropriated only after tackling the issues of corruption, transparency, impunity, and criminality, which historically have undermined foreign aid efforts. More importantly, it calls for the Central American governments to “support programs to reduce poverty, create jobs, and promote equitable economic growth in areas contributing to large numbers of migrants.”[1]

Although the goals and objectives of the bill and the Central American Strategy are worthy and deserve to be praised, caution is warranted. The implementation of these provisions will be challenging and will encounter many obstacles on the ground, such as reticence by current members of the security forces. Regardless, the incorporation of communities and members of civil society in the design of programs mentioned in Section 7045 (a) (3) (B) (iv) of the bill is a step in the right direction, which will push the Central America Strategy towards success. This section of the appropriations bill calls for “[the establishment of] policy that local communities, civil society organizations (including indigenous and other marginalized groups), and local governments are consulted in the design, and participate in the implementation and evaluation of, activities of the Plan that affect such communities, organizations, and governments.”[2] The incorporation of a policy design approach that goes from the bottom to the top is important, since this is the kind of policy that is most likely to work when fighting criminality, as highlighted by the World Bank in a June 2015 report.

Colombia

Despite focusing the majority of its efforts on the Central American migrant crisis, the U.S. omnibus bill also underscored the country’s commitment to Washington’s most loyal ally in the region—Colombia.

Despite U.S. support for the peace process in Colombia, the nature of Washington’s involvement in the South American country over the years has led some to conclude that the United States would back Colombia on almost any grounds—an intolerable notion for former President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010), who implemented the U.S.-funded Plan Colombia, leading to one of the bloodiest periods of Colombian history. Nevertheless, as peace remains a likely option for the country, according to a recent poll by Cifras y Conceptos, 61 percent of Colombians are in favor of a plebiscite to ratify the peace process.[3]

However, as peace negotiations with the FARC enter a crucial closing stage, the Colombian government has received heavy criticism in light of possible complications with the reintegration of FARC combatants, and more importantly, the development of former FARC-held territories.

The United States’ Economic Support Fund, Foreign Military Financing Program (FMF), and the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement fund compose the overwhelming majority of U.S. foreign assistance to Colombia. For 2016, Congress has provisionally granted these accounts 295.195 million USD, a four percent increase from the 283.326 million USD requested by the State Department.[4]

Through its appropriations bill, the U.S. government has committed a minimum of 133 million USD to supporting post-conflict social and economic development in Colombia through its Economic Support Fund.[5] The United States is the single largest contributor of foreign development assistance to Colombia, funds that will prove crucial particularly as the country reaches a turning point in its war-torn history by March 2016, when the final peace agreement is expected to be signed by Santos and the FARC rebels.

Post-conflict measures following Colombia’s peace process will entail enormous bureaucratic reforms, which Global Risk Insights estimates will cost the Colombian state and its private sector partners over 90 billion USD over the next 10 years.[6]

In anticipation, Colombia’s Congress passed its own appropriations measure in October, allocating 3.4 billion USD for ongoing initiatives such as humanitarian attention for victims, displaced persons, and the repatriation of land.[7] The bill also provides 15 billion USD (30 percent of the 2016 budget) in funds for the operations of the state-run Plan Nacional de Desarrollo—a novel development plan for social programs that will assume the majority of post-conflict initiatives in Colombia.[8] Despite seemingly large financial support, however, the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo was reduced by 33 percent from its proposal earlier in June.[9]

Colombia is also the largest beneficiary of the U.S. “Foreign Military Financing Program” (FMF) in the western hemisphere under the 2016 omnibus bill, receiving a total of 27 million USD.[10] The funds, however, which support the Colombian military’s main operations against the FARC and ELN guerrilla groups, come with a set of conditions. Only 19 percent of the FMF funds allocated to Colombia will be available if the country continues to: dismantle illegal armed groups; to protect the rights of human rights defenders, journalists, and trade unionists, among others; to hold accountable persons of gross human rights violations; to respect the “rights and territory of indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities”; and to ensure that members of the Colombian military who have been “credibly alleged” to have violated human rights are tried in civilian courts, rather than in military ones.[11]

The last condition put forth by the U.S. House and Senate is in response to the passage by Colombian Congress of the reform of Article 221 in Colombia’s constitution, allowing for members of Colombian military to be tried in special tribunals composed of current and former military officials.[12] The legislation, which was shot down by Colombia’s Supreme Court on two previous occasions, has been met with widespread contention, especially after the “false positive” scandal, in which 22 generals and over 5,000 members of the country’s armed forces have been accused of murdering scores of civilians and passing off their bodies as that of guerrillas.[13]

As the United States continues to assume more accountability in the region, the success of this pivot to a more structural approach will ultimately depend on measures taken by the Obama Administration and its successors in tackling one of the most complex, challenging, and unrelenting problems in the Americas—illegal drug trafficking and the U.S. demand fueling it. In spite of what changes are implemented in the U.S. drug policy, it will take years before the countries of the Northern Triangle and Colombia are free of the criminality and violence that have characterized them for so long. However, the U.S. appropriations bill, a promising sign of changes to come, represents an important step by the United States in dealing with the continuing pressing issues in the western hemisphere.

By: Santiago Baruh and Miguel Salazar, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

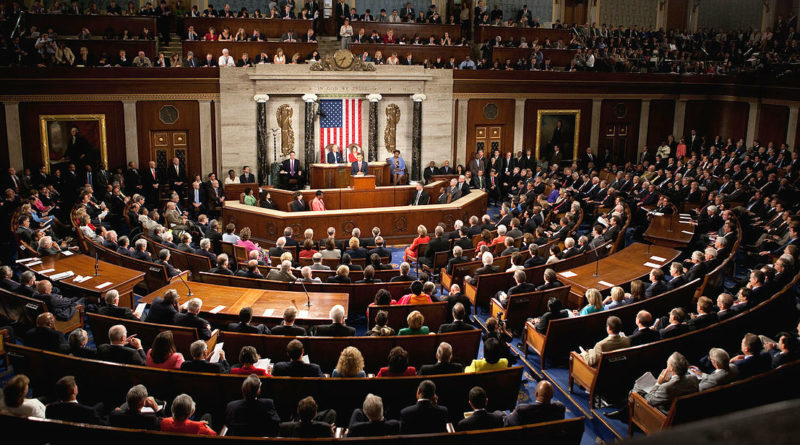

Featured Photo: President Barack Obama speaks to a joint session of Congress (Lawrence Jackson)

[1] “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016.” U.S. Congress, 1375. December 18, 2015. http://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20151214/CPRT-114-HPRT-RU00-SAHR2029-AMNT1final.pdf.

[2] Ibid

[3] “Un 61 Por Ciento De Los Colombianos, a Favor De Un Plebiscito Para Ratificar La Paz Con Las FARC.” Agencia EFE. 11 Dec. 2015. Web.

[4] These figures do not include the International Military Education and Training as well as the Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs funds, which total to a requested 5.4 million USD by the State Department. These accounts were not available in the appropriations bill. To see the requested amounts by the State Department: “Congressional Budget Justification: Foreign Operations (Appendix 3).” U.S. Department of State, 372. February 27, 2015. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/238222.pdf

[5] “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016.” U.S. Congress, 1379.

[6] Hernández, Andrés, and Daniel Lemaitre. “Economics of Peace: Colombia Lacks Post-conflict Funding.” Global Risk Insights. December 1, 2015. http://globalriskinsights.com/2015/12/economics-of-peace-colombia-lacks-post-conflict-funding/

[7] “Colombia Destinará 3.444 Millones De Dólares Al Posconflicto.” Portafolio.co. October 14, 2015. http://www.portafolio.co/economia/recursos-economicos-posconflicto-colombia-2016.

[8] Hernández, Andrés, and Daniel Lemaitre. “Economics of Peace: Colombia Lacks Post-conflict Funding.”

[9] “Conpes De La Altillanura Aún ‘navega’ Entre Nubarrones.” El Tiempo. December 14, 2015. http://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/otras-ciudades/conpes-en-vilo-por-politicas-economicas-y-sociales/16458024.

[10] “Division K- Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2016.” U.S. House of Representatives, 34. December 2015. http://docs.house.gov/meetings/RU/RU00/20151216/104298/HMTG-114-RU00-20151216-SD012.pdf

[11] “Division K- Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2016.” U.S. House of Representatives, 56-57.

[12] “Acto Legislativo No.1.” Presidencia De La República De Colombia. June 25, 2015. http://wp.presidencia.gov.co/sitios/normativa/actoslegislativos/ACTO LEGISLATIVO 01 DE 25 JUNIO DE 2015.pdf

[13] “Colombian Generals Investigated for “false Positives”” BBC News. April 13, 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-32280039.